Medical Terms

Medical Terms is in English.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Calvaria

Calvaria. The top part of the skull.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 1896 Dec 17 Stoop High Edge. Interment B. In a neighbouring recess, another large skeleton was found, which, like the former, was also contracted, and lay on the left side, but the head pointed to the S.E. The skull was much broken, but has admitted of sufficient reconstruction to give some measurements and other particulars as to the calvaria. It is brachycephalic, having an extreme length (from glabella) of 7·4 inches, and maximum breadth of 5·87 inches, but this was undoubtedly greater in life, as its left side has been slightly flattened from pressure in the grave: these measurements give a cephalic index of 79·32. It is remarkably flat-topped, a character which the late Mr. Thomas Bateman frequently observed in this class of skull in his Derbyshire and Staffordshire diggings. It is moderately thick, and its mastoid, angular, and other processes, as well as the superciliary ridges, are well developed. These, taken into consideration with the half-obliterated sutures, indicate a man in the middle period of life. A rough chipping of chert was found under the remains of the skull. The tibiae of both skeletons were markedly platycnemic.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Dolichocephalic

Dolichocephalic. Having a relatively long skull (typically with the breadth less than 80 (or 75) per cent of the length).

Description of the Chambered Tumuli of Uley and Nympsfield. A further investigation was made at the pseudo entrance at A, but no cells or chambers were found, though there were appearances that the ground had been disturbed, and pieces of broken pottery of the Roman and Romano-British period were turned up.

Nearly in the centre of the barrow, at the back of chamber C, a broken circle of stones (F in Plan J was discovered. The soil around them was deeply impregnated with wood ashes. The diameter was about 7 feet, but no remains of any kind were found near it.

In the southern end of the barrow appeared an opening leading into a small chamber (E). It appeared to be perfect and untouched. Portions of a human skull, some teeth, and a deposit of animal bones, probably wild boar, were met with in working down to it. It was walled all round, covered with three large horizontal stones, each about three feet square, but only contained pieces of broken stones.

The human remains found in the whole barrow consisted of thirty-eight skeletons of both sexes and all ages. The greater number of the skulls were so crushed and broken that they could not be restored, but it was very clear that, with one exception, they were all of dolicho-cephalic type.1 The exception was the skull found under the large stone before referred to, which, in every respect, presented a marked constrast to the other crania. It belonged to a well-developed round head. Dr. Thurnam thought this skull must have pertained to a secondary interment, but Mr. Winterbotham considered this quite impossible, and thought it more probable that this skull and the remains of the five children represented rather prisoners of war from some distinct tribe immolated in honour of those to whom the barrow was raised.2

Note 1. See Remarks of Professor Rolleston, on the Crania found in this Tumulus, ante Vol. IV., pp. 31, 3*2.

Note 2. Proc. Soc. Ant. 111., 2 S. 275.

Description of the Chambered Tumuli of Uley and Nympsfield. We have given the whole of this interesting account as being very valuable in respect to the description and plan of the tumulus, though, from the fact of its having been more than once, at early periods, disturbed and rifled, it does not afford very much information as to the "method of burial, or the character of the burial rites. Only two perfect skulls were found, and these were decidedly dolicho-cephalic. Dr. Thurnam, however, draws attention to the fact that this tumulus was an ancient monument during the Roman rule in Britain, as shown by a secondary interment near the summit accompanied by coins of the Constantine series, whilst the vessel resembling a Roman lachrymatory, found in the barrow, may possibly indicate that the interior was, in fact, broken into at this period.

Description of the Chambered Tumuli of Uley and Nympsfield. The human remains found in the Nympsfield tumulus shewed that there were not fewer than sixteen bodies therein interred. "These," Professor Buckman says, "varied in size and in age from very old to young men and women, with a few remnants of the bones of children ; so that whatever may be true as regards other tumuli of this period having been erected in honour of a chieftain here it seems quite certain that we have the remains of a family or tribe."

Among the bones found in this tumulus was one skull which is described by Dr. Thurnam as a large and finely-developed skull of a man of middle age of dolicho-cephalic type, one broken calvarium of still more decidedly dolicho-cephalic character, and fragments of, at least, ten other crania.

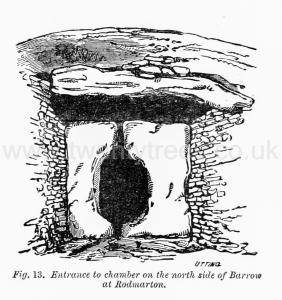

Description of the Chambered Tumuli of Uley and Nympsfield. At the northern shoulder of the tumulus was found a chamber nearly of a square form with the inner angles chamfered off. The floor was paved, and the sides were formed by seven large upright stones, and the roof by an immense single stone, nearly 9 feet by 8 feet, and 18 inches thick. It is estimated to weigh 8 or 9 tons. This chamber was entered by a very narrow passage enclosed by low dry walls on each side. The entrance was closed nearly to the top by a barrier formed of two stones placed side by side upright in the ground, and naturally hollowed out on their two inner edges so as to leave a kind of port-hole or opening of chamber could be entered. Within lay on the floor 't the skeletons of no fewer than thirteen persons, apparently of all ages and both sexes, and a few well-made flint implements. Most of the human bones showed no traces of cremation, some few had been burnt. The skulls were all of the dolicho-cephalic type. A chamber similar to the one here described was found in the southern shoulder of the barrow, which, from the confusion in which the bones were found and mixed with earth, had evidently been previously ransacked.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal. M. Broca, in his address to the French Association in 1877, showed how, on the Continent at any rate, there has been sufficient evidence to satisfy him and other foreign geologists, proving the existence of at least three races of men who succeeded one another in Europe, before the dawn of history. I must however state, before giving an outline of this evidence, that it is not altogether accepted in this country, and at present the conclusions derived from the discoveries in certain foreign caves, of human bones associated with tl.re Pleistocene fauna, must be received with very considerable doubt. According to M. Broca's account, in his address last year, there seems to have been first a strongly-marked dolicho-cephalic or long-headed race, which has been called that of Canstadt, the locality where certain bones of man were found in conjunction with implements of a very rude type; the nearest approach to this race of man, as far as physical conformation goes, is to be found amongst the Esquimanx and the natives of Australia. But a few fragmentary skulls and bones were found in the Canstadt cave, but these men may be looked upon as the makers and users of the rudest implements of the river gravels and of the caverns, and the contemporaries of the extinct Mammalia; they were replaced by another race more advanced in several respects, although also a long-headed one, but of a higher type, according to M. Broca, and of taller stature, a race also which showed signs of a more advanced civilization; it has been named after the cave of Cromagnon, in which some human skeletons were found side by side with Pleistocene remains; but whether these skeletons were really of the same date as those remains of the Pleistocene age, must be open to question; and Professor Boyd Dawkins has shown good reason why we should suspend our judgment as to the evidence of Cromagnon, but should it be possible to establish this race, it is to it that we must assign the more perfectly fashioned implements of the later Palaolithic age; they also made use of bone for various purposes, sometimes ornamenting their bone tools with considerable skill; the engravings on bone found in some of the caves of the Vezbre-the Madeleine amongst others and in Belgium and elsewhere, may be attributed to these men; they were contemporaries, as were their predecessors, of the pleistocene animals, and seem at any rate for the most part to have disappeared with them. A very short race is said to have followed the men of Cromagnon, named after the caverns of Furfooz in Belgium: their civilization seems to have been of a lower character, although they possessed the art of making pottery. The Reindeer and the Glutton appear to have been still existing, their bones having been found with those of these men.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Glabella

Glabella. The part of the skull between your eyes, above the nose.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 1896 Dec 17 Stoop High Edge. Interment B. In a neighbouring recess, another large skeleton was found, which, like the former, was also contracted, and lay on the left side, but the head pointed to the S.E. The skull was much broken, but has admitted of sufficient reconstruction to give some measurements and other particulars as to the calvaria. It is brachycephalic, having an extreme length (from glabella) of 7·4 inches, and maximum breadth of 5·87 inches, but this was undoubtedly greater in life, as its left side has been slightly flattened from pressure in the grave: these measurements give a cephalic index of 79·32. It is remarkably flat-topped, a character which the late Mr. Thomas Bateman frequently observed in this class of skull in his Derbyshire and Staffordshire diggings. It is moderately thick, and its mastoid, angular, and other processes, as well as the superciliary ridges, are well developed. These, taken into consideration with the half-obliterated sutures, indicate a man in the middle period of life. A rough chipping of chert was found under the remains of the skull. The tibiae of both skeletons were markedly platycnemic.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Globose

Globose. Having the form of a globe; spherical.

Finds Near Stow on the Wold. Stow. — Not a stone's throw from S. Edward's Hall, on the north-east corner of the square, on the east side, at the back of the passage of the first doorway, was lately found a skeleton, in a cavity in the rock, just below the surface, N.N.W. and S.S.W., and pronounced by Dr. Rolleston to be Roman "well filled out globose skull, with the width on the crown, so characteristic of the Roman skull." Outside the town, in the first quarry, on the right, on the Moreton road, lay the Saxon, with a spear-head 18 inches long, a foot of which is the sharp-pointed blade. It was the weapon of one who may have fallen on the spot, afterwards immortalizing Stow and Donington its hamlet, where Royalist and Parliamentarian were together locked in their last mortal decisive struggle. Hard by, fell Capt. Keyte. Within earshot, or at most, gunshot. Sir Jacob Astley (seated on a drum) gave his captors his well-known shrewd and laconic counsel.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Glyster

Glyster. An enema, also known as a clyster, or glyster, is an injection of fluid into the lower bowel by way of the rectum.

Pepy's Diary. 12 Oct 1663. Up (though slept well) and made some water in the morning [as] I used to do, and a little pain returned to me, and some fears, but being forced to go to the Duke (age 29) at St. James's, I took coach and in my way called upon Mr. Hollyard (age 54) and had his advice to take a glyster. At St. James's we attended the Duke all of us. And there, after my discourse, Mr. Coventry (age 35) of his own accord begun to tell the Duke how he found that discourse abroad did run to his prejudice about the fees that he took, and how he sold places and other things; wherein he desired to appeal to his Highness, whether he did any thing more than what his predecessors did, and appealed to us all. So Sir G. Carteret (age 53) did answer that some fees were heretofore taken, but what he knows not; only that selling of places never was nor ought to be countenanced. So Mr. Coventry (age 35) very hotly answered to Sir G. Carteret (age 53), and appealed to himself whether he was not one of the first that put him upon looking after this taking of fees, and that he told him that Mr. Smith should say that he made £5000 the first year, and he believed he made £7000. This Sir G. Carteret (age 53) denied, and said, that if he did say so he told a lie, for he could not, nor did know, that ever he did make that profit of his place; but that he believes he might say £2500 the first year. Mr. Coventry (age 35) instanced in another thing, particularly wherein Sir G. Carteret (age 53) did advise with him about the selling of the Auditor's place of the stores, when in the beginning there was an intention of creating such an office. This he confessed, but with some lessening of the tale Mr. Coventry (age 35) told, it being only for a respect to my Lord Fitz-Harding (age 33). In fine, Mr. Coventry (age 35) did put into the Duke's hand a list of above 250 places that he did give without receiving one farthing, so much as his ordinary fees for them, upon his life and oath; and that since the Duke's establishment of fees he had never received one token more of any man; and that in his whole life he never conditioned or discoursed of any consideration from any commanders since he came to the Navy. And afterwards, my Lord Barkeley merrily discoursing that he wished his profit greater than it was, and that he did believe that he had got £50,000 since he came in, Mr. Coventry (age 35) did openly declare that his Lordship, or any of us, should have not only all he had got, but all that he had in the world (and yet he did not come a beggar into the Navy, nor would yet be thought to speak in any contempt of his Royall Highness's bounty), and should have a year to consider of it too, for £25,000. The Duke's answer was, that he wished we all had made more profit than he had of our places, and that we had all of us got as much as one man below stayres in the Court, which he presently named, and it was Sir George Lane (age 43)! This being ended, and the list left in the Duke's hand, we parted, and I with Sir G. Carteret (age 53), Sir J. Minnes (age 64), and Sir W. Batten (age 62) by coach to the Exchange [Map], and there a while, and so home, and whether it be the jogging, or by having my mind more employed (which I believe is a great matter) I know not, but.... I begin to be suddenly well, at least better than I was.

Pepy's Diary. 13 Nov 1663. That done home to my wife to take a clyster, which I did, and it wrought very well and brought a great deal of wind, which I perceive is all that do trouble me. After that, about 9 or 10 o'clock, to supper in my wife's chamber, and then about 12 to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 10 Apr 1664. Lord's Day. Lay long in bed, and then up and my wife dressed herself, it being Easter day, but I not being so well as to go out, she, though much against her will, staid at home with me; for she had put on her new best gowns, which indeed is very fine now with the lace; and this morning her taylor brought home her other new laced silks gowns with a smaller lace, and new petticoats, I bought the other day both very pretty. We spent the day in pleasant talks and company one with another, reading in Dr. Fuller's book what he says of the family of the Cliffords and Kingsmills, and at night being myself better than I was by taking a glyster, which did carry away a great deal of wind, I after supper at night went to bed and slept well.

Pepy's Diary. 14 May 1664. After dinner my pain increasing I was forced to go to bed, and by and by my pain rose to be as great for an hour or two as ever I remember it was in any fit of the stone, both in the lower part of my belly and in my back also. No wind could I break. I took a glyster, but it brought away but a little, and my height of pain followed it. At last after two hours lying thus in most extraordinary anguish, crying and roaring, I know not what, whether it was my great sweating that may do it, but upon getting by chance, among my other tumblings, upon my knees, in bed, my pain began to grow less and less, till in an hour after I was in very little pain, but could break no wind, nor make any water, and so continued, and slept well all night.

Pepy's Diary. 16 May 1664. Thence walked to Westminster Hall [Map], where the King (age 33) was expected to come to prorogue the House, but it seems, afterwards I hear, he did not come. I promised to go again to Mr. Pierce's, but my pain grew so great, besides a bruise I got to-day in my right testicle, which now vexes me as much as the other, that I was mighty melancholy, and so by coach home and there took another glyster, but find little good by it, but by sitting still my pain of my bruise went away, and so after supper to bed, my wife and I having talked and concluded upon sending my father an offer of having Pall come to us to be with us for her preferment, if by any means I can get her a husband here, which, though it be some trouble to us, yet it will be better than to have her stay there till nobody will have her and then be flung upon my hands.

Pepy's Diary. 16 Jul 1666. Up in the afternoon, and passed the day with Balty (age 26), who is come from sea for a day or two before the fight, and I perceive could be willing fairly to be out of the next fight, and I cannot much blame him, he having no reason by his place to be there; however, would not have him to be absent, manifestly to avoid being there. At night grew a little better and took a glyster of sacke, but taking it by halves it did me not much good, I taking but a little of it. However, to bed, and had a pretty good night of it,

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Manus Christi

Manus Christi, Literally 'the hand of Christ'. A cordial made by boiling sugar usually with rose water or violet water and formerly given to unwell people.

Letters and Papers 1528. 28 Jun 1528. R. O. 4429. HENNEGE to WOLSEY.

The King removed this day from Hertford to Hatfield because of the sweat. My Lord Marquis, his wife, Mr. Chene, the Queen's almoner, Mr. Toke, are fallen sick, and the Master of the Horse (age 32) complains of his head. Nevertheless, the King is merry, and takes no conceit (?), but heartily recommends him to you, and prays you to [do] as he does. Yesterday the King sent Wolsey [as a] "preservative, manws cresty" (manus Christi), with divers other things.

Hol., p. 1. Sealed and add.

Culture, General Things, Dictionaries, English, Medical Terms, Pills of Rasis

Pills of Rasis. Named after the 10th Century Persian physican Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī aka Abu Bakr al-Razi.

Letters and Papers 1528. 23 Jun 1528. 4409. When I came to that part of your letter mentioning your counsel to the King for avoiding infection he thanked your Grace, and showed the manner of the infection; how folks were taken; how little danger there was if good order be observed; how few were dead of it; how Mistress Ann (Boleyn) (age 27) and my Lord Rochford (age 25) both have had it; what jeopardy they have been in by the turning in of the sweat before the time; of the endeavor of Mr. Buttes (age 42), who hath been with them in his return; and finally of their perfect recovery. He begs you will keep out of infection, and that you will use small suppers, drink little wine, "namely, that is big," and once in the week use the pills of Rasis; and if it come, to sweat moderately, and at the full time, without suffering it to run in, &c.