Effigy of King Richard I

Effigy of King Richard I is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

THIS chivalrous monarch, the fame of whose personal courage has been handed down to posterity in his surname, Coeur de Lion, was the third son of Henry the Second, by Eleanor de Guienne, his queen, and was born at Oxford, at the royal palace there, in the year 1157. He was created Earl of Poitou and Duke of Aquitaine by his father, during his lifetime, and at his death in 1181 succeeded to the Crown of England. In his childhood he was contracted in marriage to Alice, daughter of Henry the Seventh, King of France [Note. A mistake for Louis VII]. This engagement was, however, never completed; her chastity lying under an imputation with his own father, he refused to ratify it, and gave £100,000. to King Philip, her brother, as a compensation for its non-performance. She became the wife of William Earl of Ponthieu, by whom she had issue Joan of Castile, mother of Queen Eleanor, wife of Edward the First. [Note. A mistake. William and Alice were the parent of Marie Montgomery Countess Ponthieu who was the mother of Joan Dammartin Queen Consort Castile and Leon who was the mother of Eleanor of Castile Queen Consort England]

His second wife [Note. A mistake? His first wife - he and Alice were only betrothed?] was Berengaria, or Berenquelle, daughter of Sanchez the Fourth, King of Navarre. She was married to Richard in 1190, at the Island of Cyprus, when on his way to the Holy Land, whither she accompanied him.

King Richard received the scrip and staff of pilgrimage from the Archbishop of Tours, and proceeding to Marseilles, embarked on the 7th August 1190, on his expedition to the Holy Land. His first exploit in his way was the capture of the city of Messina, in Sicily, in order to release his sister Joan, widow of William the Good, the late king of that island, then kept in confinement by Tancred, the bastard and usurper. Richard enforced his demands of remuneration for his sister's claims, by keeping possession of Messina until they were satisfied. These were, that Tancred should permit her to enjoy the dower settled on her by the late King her husband; that she should have, according to the custom of Sicilian queens, a chair of gold, a table of gold twelve feet in length and a foot and a half in breadth, two golden tressels to support the same, a silk tent in which two hundred knights might be entertained, twenty-four silver cups and as many dishes, six thousand measures of wheat, a proportionate quantity of barley and wine, an hundred armed galleys, properly appointed, and victualled for two years. Tancred compounded for these dues by the payment of twenty thousand ounces of gold to Richard as his sisters dower, twenty thousand more to Richard himself, to be quit of any further claims, besides a gift to him of four large ships and fifteen galleys. Setting sail from Sicily, accompanied by his mother Eleanor and his betrothed wife, his fleet was scattered in a tempest between the islands of Rhodes and Cyprus. The ship which contained his sister Joan and his intended bride, was barbarously excluded from sheltering in Cyprus by Isaac Comnenus, the reigning prince, who held it under the Greek emperors. Richard promptly avenged this affront, by subduing the island, taking Isaac prisoner, and ultimately transferring the sovereignty of Cyprus to Guy de Lusignan. Here Richard espoused his queen Berengaria. In the beginning of April 1191 Richard proceeded to the relief of the Christian army encamped before Acre. In his voyage he fell in with a Saracen dromond, or huge argosie, sent by Saladin, the brother of Saladin the Soldan of Babylon, laden with immense treasure, military stores, and provisions, and fifteen hundred warriors, for the succour of the Infidels besieged in Acre. Among the articles for offensive warfare were a quantity of the celebrated Greek fire, and vessels full of venomous serpents. This unwieldy vessel was promptly assailed on all sides by the King's light galleys; her bottom was pierced with holes by the augers of certain dextrous divers, and she was soon filled with water to her upper works. Thirteen hundred of her crew were consigned by the King's order to the waves; two hundred remained his prisoners. Richard arrived at Acre in the middle of June, with his gallant fleet of two hundred and fifty ships and sixty galleys, and aided so vigorously the combined forces of Christendom in the prosecution of the siege, that on the twelfth of the following July the city surrendered. The defection of Philip King of France did not damp the ardour of Richard: he marched against Jerusalem, and in sight of that city attacked and overthrew the caravan of Saladin, which came laden from Babylon, under an escort of ten thousand men. A truce being concluded with Saladin, Richard bent his steps homeward, to regulate the domestic concerns of his Realm, and to procure reinforcement for his crusading host. In his way he was shipwrecked near Aquileia, but getting safely to land he disguised himself as a merchant, and assuming the name of Hugh, was making his way through the Austrian dominions, when he was discovered and made prisoner by Leopold Duke of Austria, who owed him an old grudge for an indignity offered to his banner at Acre. Richard was given up by him to the Emperor of Germany, of whom he was obliged to purchase his liberty by a heavy ransom, 130,000 marks of silver. The old disagreement between Richard and Philip of France continuing unallayed, a war between them was the consequence, and Richard gave him a signal overthrow at the famous battle of Gisors, in Normandy, where the French king narrowly escaped with his life. The lion-hearted Richard on this occasion eminently displayed his intrepid character, and exclaimed after the held was won, "Not we but 'God and our Right' have vanquished France at Gisors;" the same emphatic words were by one of his successors coupled with the armorial ensigns of the British Crown.

Shortly after it was Richard's fate to lose his life in a petty feud. The Count of Limoges, a dependant on the Dukes of Aquitaine, having found a treasure on his land, Richard, as lord paramount, laid claim to the whole, and to enforce his right, besieged the Castle of Chaluz, where it was supposed the treasure was deposited. He was wounded by a quarrel, from the steelbow of an arbalister on the ramparts of the Castle. Hearing the twang of the implement, he stooped forward to avoid the shot, and in consequence of that movement received it in his left shoulder. The barbed head of the arrow remained in the wound, the severity of which was much increased by the attempts of an unskilful surgeon to cut it out. The Castle being taken, and the archer brought before the King, he justified the deed, by saying that Richard with his own hand had killed his father and his two brothers. The King, with a true magnanimity, commanded him to be set at liberty with a reward of a hundred shillings; an order basely disregarded after the King s death by one of his mercenary chiefs, who caused the arbalister to be flayed alive and hanged. Richard having received the Sacraments of the Church, died in the fortress above-mentioned on Tuesday 6th April 1199, after a reign of nine-years and nine months. He directed his heart to be carried to his faithful city of Rouen for interment in the Cathedral; his bowels, as his ignoble parts, to the rebellious Poictevins; and his body to be buried at the feet of his father Henry the Second at Fontevraud. This gave rise to the following Leonine verses, which are quoted by Matthew Paris as having been written for him by some rhimer of the day by way of epitaph, in which the idea that so mighty a ruin was too great for one place, is not destitute of point:

Pictavus exta ducis sepelit tellusque Chalutis; [Pictavus buried the existence of the leader and the land of Châlus]

Corpus dat claudi sub marmore Fontis Ebraudi; [The body is closed under the marble of the Fontevraud]

Neustria, tuque tegis cor inexpugnabile regis; [Neustria (Rouen?), and you cover the impregnable heart of the king]

Sic loca per trina te sparsit tanta ruina. [Thus you were scattered in three places by so great a fall]

Non fuit hoc funus cui sufHceret locus unus. [This was not a funeral for which one place would suffice]

Over his gilt monument, according to Sandford, was the following inscription (probably on a suspended tablet, being a summary of his most celebrated exploits:

Scribitur hoc tumulo, rex auree, laus tua tota [It is written on this tomb, golden king, all your praise]

Aurea, materise conveniente nota: [A golden, materially appropriate note]

Laus tua prima fuit Siculi, Cyprus altera, dromo [Your first praise was Sicily, the second Cyprus, Dromo]

Tertia, caravana quarta, suprema Ioppe; [The third, the fourth caravan, the highest of Joppa]

Suppressi Siculi, Cyprus pessundata, dromo [The Sicilies were suppressed, Cyprus was beaten,]

Mersus, caravana capta, retenta loppe. [He sank, the caravan was captured, and the ship was captured]

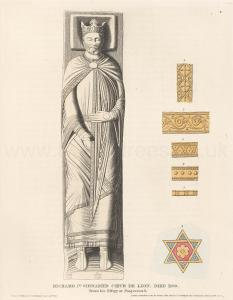

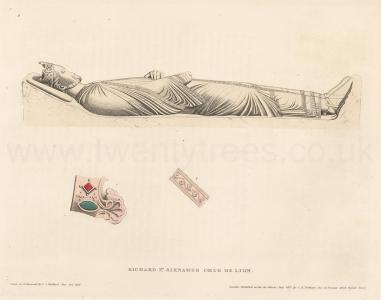

he figure of Richard the First reposes on a bier covered with drapery. He wears a crown, the trefoils of which are Riled up with a honeysuckle pattern, which various architectural remains of the same period shew to have been then much in vogue. His royal mantle is painted blue with an ornamental gold border, his dalmatic or supertunic is red, his tunic is whitea, and under this appears his camise or shirt. The boots are adorned with broad ribband like stripes of gold, which appear to have been intended to express the earlier mode of chaussure sandals. The leather of the spurs are visible.

Details. Plate I. 1. The border of the mantle. 2. Girdle. 3. The border of the dalmatic. 4. The border of the tunic. 5. The border of the camisole or shirt. 6. Ornaments on the cover of the feretrum or bier. Plate II. The Crown.

Note a. These three garments were ecclesiastical, answering to the bishop's chasuble or cope, the deacon's dalmatic, the subdeacon's tunic. The Church herself perhaps originally derived them from the imperial costume, in order to denote the spiritual authority of her ministers.