Introduction

Introduction is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

INTRODUCTION.

ORIGINALITY of design may be justly claimed for the Author of "The Monumental Effigies of Great Britain;" for, blending at once the character of the Artist and the Antiquary, he has aimed at showing the progress of sculptural science in the memorials extant for the illustrious dead, regarding them, not simply as monumental records, but also as the most efficient means of bringing before our view the characters of English History, in their "habits as they lived."

A severe course of study, in those only schools for correct drawing, the Antique Greek sculptures and the living model, a firm and delicate hand, a most discriminating taste, and an undeviating principle of truth in all he drew, peculiarly fitted him for the undertaking. He seized and transferred to his paper every good point in the original subjects before him. He exaggerated nothing; he let no beauty escape him. The proof of these assertions will be found in the Plates of this work; and there needs little apology in having said thus much in praise of its Author, on its being now presented to the public in a complete form. He has been some years beyond the shafts of envy or malevolence, and his own frank but modestly-expressed prediction will be accomplished, that sooner or later "his labours will find their valuea." Grateful, indeed, would it have been to those who now survive him, if he had himself lived fully to reap the applause due to his labours, and if the pen which has ventured to complete the letter-press of the Monumental Effigies had been spared the task. That task has, however, been executed with a feeling of zeal inspired by the subject, and of reverence for the talents and worth of the departed Author. A tribute imperfect, inadequate, but sincere, "Hunc saltern accumulem donis et fungar inani Munere "-

Note a. "I do not conceive I have done more than any one else might, with patience and attention; yet still I cannot he deceived as to what must be the product. I am well convinced that, some time or other, my labours will find their value. "Original Letter, in Memoirs and Correspondence of Charles Alfred Stothard, F.S.A. by Mrs. Charles Stothard (age 29) (now Mrs. Bray), Author of Letters during a Tour through Normandy, &c. Longman and Co. 1823, p. 97.

Mr. Charles Stothard had proceeded as far as the Ninth Number of his Work, when his honourable career was arrested by the mysterious decree of Providence. His widow, now the wife of the Rev. Edward Atkyns Bray, has, with the praiseworthy approbation of her husband, neglected, since that event, no effort to do justice to Mr. Stothard's memory, and spared no expense within her means to give completion to his great undertaking.

Mr. Charles Stothard left behind him some materials towards the Introduction to his work, which are interspersed in the Memoir of his Life, before cited. These will be duly respected here.

The following sketch of a prefatory Essay was found among his papers: "It is one of the most striking features of the human mind, that it invariably embodies and gives form to description, more or less strong and perfect, as the mind is gifted and cultivated; and it is from this property in man that the study of antiquity, as connected with and illustrative of history, is the source of some of the greatest intellectual pleasures we are capable of enjoying. By these means we live in other ages than our own, and become nearly as well acquainted with them. In some measure we arrest the fleeting steps of Time, and again review those things his arm has passed over, and subdued, but not destroyed. The researches of the Antiquary are worthless if they do not impart to us this power, or give us other advantages; it is not to admire any thing for its age or rust that constitutes the interest of the object, but as it is conducive to our knowledge, the enlargement of human intellect, and general improvement.

"Among the various antiquities which England possesses, there are none so immediately illustrative of our history as its national monuments, which abound in our cathedrals and churches. Considered with an attention to all they are capable of embracing, there is no subject can furnish more various-or original information. Scattered in ail directions, and very remote fr om each other, they have hitherto possessed but a negative value; it is therefore both useful and interesting, by means of the pencil, to bring them together in the form of a collection; and in some degree, it is to be hoped, such an attempt may give a check to, and serve to counteract, the unfeeling ignorance so prevalent in the taste displayed for beautifying and whitewashing these vestiges; a custom which has already destroyed so much, and still continues to make the most dreadful ravages among these records of past ages. The destruction by time and accident bears, in comparison with this, but small proportion, although it adds to the claim these subjects have upon our attention, to save them from total oblivion.

"The present work was undertaken from a conviction that nothing effectual towards this last-mentioned purpose had been accomplished, as well as to afford an interesting illustration of history, the progress of art and sculpture, with the changes in costume of different periods in this country. "Of the progress of sculpture I shall presently speak at large; and of costume I may here observe, that we have many proofs that the various dresses which present themselves to us on our Monumental Effigies, were not at all introduced by any inventive or whimsical fancies in the sculptor. Several agree with our MS. illuminations of their various periods; and we never observe any thing, however singular, but we are sure to detect it repeated in the same age on some other subject. It may be also remarked, that, with very few exceptions, these effigies present the only existing portraits we possess, of our Kings, our Princes, and the Heroes of ages famed for chivalry and arms. Thus considered, they must be extremely valuable, and furnish us not only with well-defined ideas of celebrated personages, but make us acquainted with the customs and habits of the time. To history they give a body and a substance, by placing before us those things which language is deficient in describing.

"Comparatively speaking, we shall be able to ascertain less in the few centuries into which our inquiries lead us, than in the ages of the Greeks and Romans. The reason, I think, is obvious: as the Arts in this country had their birth in religion, and were confined to the adornment of religious edifices, Architecture, Painting, and Sculpture were no where to be found but under the Church, supported by the munificence of Princes, and the vast revenues arising from Monasteries so richly and splendidly endowed. How different was the spirit which animated the Pagan and the Gothic ages! With the Greeks and Romans, not only the temples of their gods, but their cities, and even their private houses, were adorned with works of art. Amongst our monkish historians, we neither find a Diodorus Siculus nor a Strabo. Had the subject of the Gothic Arts been more political, history would have been imperfect, if it omitted accounts of things so intimately connected with it. I intended, on the commencement of my work, to have given a history of the rise of Arts in this country, as far as they were connected with sculpture; but, on looking further into the subject, I found materials too few; and those of such a nature, that the time required to make researches in this particular would be enough of itself without thinking of giving specimens, &c. The earliest tombs of this country, since the Conquest, appear to us in the shape of the lid of the coffin. These seem to have been placed even with the pavement, having, in some instances, foliage fancifully sculptured upon them, and in others crosses, with various fanciful devices, but most generally with such as denoted the profession of the deceased. These were carved in exceeding low relief Tombs of this description are extremely numerous. As examples, a few will be selected of the most curious. From some interesting specimens we have prior to the Conquest, we may gather that such a mode was very early practised in this country."

In pursuance of this intention, Mr. Stothard made a drawing of the lid of the stone-coffin of Queen Matilda, at Caen, an etching from which is here inserted. We have in this drawing a careful facsimile of an inscription in the Roman character, as employed in the Gothic age. The chief variations are to be found in the form of the C, E, H, G, Q, and Z; and of the three first letters, the pure Roman form is used as well as the other. It may, indeed, be suspected that the alteration began with the Romans of the Lower Empire themselves. The upright strokes of letters in this inscription are sometimes blended together, so as to make one upright stroke serve for two letters, as the last stroke of an N for the first of a D; in one instance, a single letter is made to end and begin a word, as QUAMULTIS for QUAM MULTIS; small letters are put within larger, &c.; practices not unknown, we believe, to the Romans, in their inscriptions, when they wished to contract them within a limited space. A curious example of this kind, in the inscription on the tomb of the Anglo-Saxon Princess Editha, at Magdeburg, was communicated in 1830 by the Rev. Edward Kerrich, F.S.A. to the Gentleman's Magazinea. The round uncial character, so called either from its size or its initial station in MSS. came into use on tombs in the thirteenth century, and was superseded by the black-letter towards the close of the fourteenth.

Note a. Gents. Mag. vol. C. i. 195. She was the daughter of King Edmund.

Matilda was the daughter of Baldwin Earl of Flanders, was married to William Duke of Normandy before his successful invasion of England, and was crowned as his Queen Consort of that Country in 1068. She died in 1083, and was buried in the church of the Holy Trinity, founded by herself at Caen. The following is the epitaph inscribed on her coffin-lid:

"EGREGIE PULCHRI TEGIT HEC STRUCTURA SEPULCHRI

MORIBUS INSIGNE' GERMEN REGALE MATHILDEM [Queen Matilda]

DUX FLANDRITA PATER HUIC EXTITIT ADALA MATER [Her father was the Duke Flanders, her mother Adela]

FRANCOR' GENTIS ROTBERTI FILIA REGIS [daughter of King Robert of France]

ET SOROR HENRICI REGALIS EDE POTITI [And sister of King Henry I of France]

REGI MAGNIFICO WILLELMO JUNCTA MARITO [King William the Magnificient her husband]

PRESENTEM SEDEM PRESENTE' FECIT ET EDEM

TAM MULTIS TERRIS QUAMULTIS REBUS HONESTIS

A SE DITATAM SE PROCURANTE DICATAM

HEC CONSOLATRIX INOPUM PIETATIS AMATRIX

GAZIS DISPERSIS PAUPER SIBI DIVES EGENIS

SIC INFINITE PETIIT CONSORTIA VITE

IN PRIMA MENSIS POST PRIMAM LUCE NOVEMBRISa."

Note a. Mrs. Charles Stothard's Tour in Normandy, &c. p. 101.

The reader will be amused by comparing this version with the inscription in the etching, and observing the expedients which were resorted to in order to bring it within the limits of the stone. To Mr. Stothard's observations on stone-coffins may be added, that they were the receptacles of the distinguished dead Rom a very early perioda. A Roman stone-coffin of very massive construction, having a coped lidb, was laid open at the excavations made in 1828 at a spot near Caesar's Camp, Holwood Hill, in Kent, where are still visible the remains of a small temple, or sacellum, in connection with Roman sepulchres. This coffin was deposited in a grave cut eight feet deep in the chalk rock. The coped form of the lid was particularly well calculated for carrying off the moisture from the interior, whether above or under ground. Accrdingly, we find in the coffin in which the body of William Rufus was deposited, the same form continued which had been adopted by the half-civilized people of Europe, like the details of their architecture, on the Roman model. The coped shape of the lid was no doubt very early varied by the flat, (particularly when the defunct was deposited under the roof of a sacred building, where no moisture was to be repelled, and the coffin lid could be thus reduced to the level of the door,) but it remains one mark of the antiquity of sepulchral chests in the Middle Age. We resume Mr. Stothard's prefatory notes:

"Effigies are rarely to be met with in England before the middle of the thirteenth century; a circumstance not to be attributed to the causes generally assigned, which were, either that they had been destroyed, or that the unsettled state of the times did not offer sufficient encouragement for erecting such memorials: but it rather appears not to have been before become the practice to represent the deceased. If it had been otherwise, for what reason do we not find effigies over the tombs of William the Conqueror, his son, William Rufus, or his daughter, Gundrada [Note. No daughter of William the Conqueror named Gundrada is known? She is probably Gundred Countess of Surrey wife of William Warenne 1st Earl Surrey, daughter of Gerbod The Fleming, who was, for some time, believed to be a daughter of William the Conqueror]. Yet, after a time, it is an undoubted fact that the alteration introduced by the Normans was the addition of the figure of the person deceased; and then it appeared not in the bold style of the later Norman monuments, but partaking of the character and low relief of those tombs it was about to supersede. Of these, and of the few, perhaps, that were executed, Roger Bishop of Sarum is the only specimen in good preservation. The effigy of Joceline Bishop of Salisbury is infinitely more relieved than that of Roger Bishop of the same see, which is far from possessing the bold relief we afterwards observe in the figure of King John. Our sculptors, having arrived at this stage of improvement, continued to execute their effigies after the same manner, (during which we observe the coffin-shaped slab giving way to a more regular figure,) till the beginning of the fourteenth century; and it was then that it entirely disappeared, and that the effigy is represented in full relief To support such a conjecture is no difficult task * * * as by the appearance of King John's remains, and other instances. "Withburg, a sister to Queen Etheldreda, Abbess of Ely, when examined, several centuries after her interment, by order of the Abbot Richard, was found with a cushion of silk beneath her head, &c. It is not unlikely that it was usual to bury the dead in this manner; whence arose the custom of sculpturing our effigies with cushions under the head. Henry the Second's effigy, at Fontevraud [Map], is thus represented, and agrees with the account given by Matthew Paris, and other writers, of that monarch's appearance after death, when placed upon the bier; and Berengaria, Queen of Richard the First, is seen in her effigy holding a book, the cover embossed with a second representation of herself (which agrees with the effigy), lying upon a bier, with waxen tapers burning in candlesticks on either side. Yet it is probable the custom of burying the dead in the dress which marked the habits of their lives was not universal; for, had it been so, we should find knights in their armourc, which would have explained points that now, probably, will never be clearly understood.

Note a. Cremari apud Romanos non fuit veteris instituti: terra condebantur; et postquam longinquis bellis obrutos erui cognovere est institutum, et tamen multse familise priscos servavere ritus. [Among the Romans cremation was not an ancient institution: they were laid in the earth; and after having been rescued from distant wars, it was determined to know the institution, and yet many families kept the ancient rites] Manutius de leg. Rom.

Note b. See Archæologia, Vol. XXII. Plate xxxii. p. 348.

Note c. The value of armour in an iron age, when the suit descended from sire to son, or was bequeathed as "a rich legacy," may account for the omission of this practice.

"It is true that a very voluminous work of this kind has been published by the late Mr. Gough, which Was undertaken with the best intentions; but, whatever information we may receive from his writings, the delineating part is so extremely incorrect, and full of errors, that at a future period, when the originals no longer exist, it will be impossible to form any correct idea of what they really were. It may, perhaps, be thought unjust that I should enter so little into the merits of a work which has challenged considerable notice; but delicacy, united to the wish of depreciating as little as possible the well-intentioned endeavours of another, would altogether make me silent, did I not feel that, in justice to myself, and as the present work is situated, something must be said, or the errorsa of Mr. Gough might at a future period be the means of injuring an attempt, which differs from his on account of its very accuracy. * * * * * * Had Mr. Gough been draughtsman sufficient to have executed his own drawings, he might have avoided the innumerable mistakes which, from circumstances, and the nature of the subject, must unavoidably have arisen. He could not transfer that enthusiasm which he himself felt to the persons he employed, to enable them to overcome such difficulties. Of what nature these were, and how they acted upon interested people, can be easily shown. There are innumerable instances where the effigies are covered with plaster and whitewash, so as to conceal, not only the true form, but the ornaments upon it. Such disfigurement cannot be removed by the unfeeling hand of a labourer; and can it be supposed that a mere draughtsman, employed upon a work of which he is not the proprietor, will take upon himself the disagreeable and unprofitable task of clearing the surface of a subject, which his employer will probably never see or examine? For it is remarkable that the most curious specimens I have found, and given in my work, presented, at first sight, nothing which could excite the least interest, till, with infinite trouble, time, and labour, I disincumbered them of their whitewash, plaster, and house-painting cases, when the figures, dresses, and ornaments, frequently came forth in a state sufficiently clear and perfect to be entirely made out."

Note a. It will be observed that Mr. Stothard speaks, all through these remarks, of the errors which arose from the misresentations of the subjects by Mr. Gough's draughtsmen. Nothing could be further from his mind than any envious motive, or to depreciate the zeal, research, and learning displayed by Mr. Gough's undertaking.

The military costume, from the military character of the Middle Ages, necessarily forms a most prominent feature in the Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. The rent of the tenant in capite was military service; and every great landholder, therefore, became a knight. The mail and the plate, in modern days, have been stripped from under the surcoat, or "cote armure," of our Gentry, but they still retain the distinctive emblazonments with which the surcoat was wrought, as the badge of their noble descent, and thus have perpetuated the pride of chivalry; not, indeed, speaking in a limited sense, reprehensible, for, when associated, as it always assumed to be, with religion, it leads to actions "Sans peur et sans reproclie [Without fear and without reproach]."

Ancient armour may be classed under three distinct periods. In the first, the outward defence of the body was chiefly composed of mail, (to apply that as a general term for armour formed of minute pieces, and not strictly with a view to its derivation); that mail was either of small plates of metal, like fish scales, of square or lozenge-shaped plates, or mascles, or of rings, which, perhaps, were not at first interlinked and rivetted together, but sewn down upon quilted cloth. Examples of all these will be seen by reference to the prints of the Bayeux Tapesty, published by the Society of Antiquaries of London, after Mr. Charles Stothard's original drawings.

With this defensive clothing for the body was worn a conical steel cap with a nasal, and a long kite-shaped shield. Pot-shaped helmets, flat at the top, and spherical chapelles-de-fer, were also among the early defences for the head. These were sometimes worn under the hood of the hauberk; which will account for the forms that the chain-mail armour in some instances assumes, on figures represented in our effigies and seals.

In the second period, the mail was externally strengthened about the arms and legs with plates of iron. A helmet covering the head and face was introduced, or a moveable ventaille, or baviere, was added, for the same purpose, to the scull-cap.

The third period inclosed the body from head to loot in plate of steel, and the chain-mail only makes its appearance at the or armpit joints of the armour, either as gussets, or worn under-neath, as a haubergeon, or lighter shirt of maila. The camail, or gorget of mail, so called from its being attached by a lace to the basinet, or cap, was, on account of the pliability which it afforded to the motion of the neck, at first retained, but was ultimately displaced by a gorget of plate. To the breastplate the protuberant form of a pigeon's breast was given, particularly well calculated to glance off the thrust of a spear, and to prevent the body from being injured by blows causing deep indentations in the armour. The term hauberk seems to have been used either for the corselet, or body-armour of mail or of plate. Chaucer thus describes the armour of a knight, in his 'Rhime of Sir Thopas':

'He did on next his white lere

Of cloth of lake full line and clere,

A breche, and eke a sherte.

And next his sherte an hakaton,

And ovir that an hagergeon

For percing of his herte;

And over that a fine hauberke

Was all ywrought of Jewis werke;

Full strong it was of plate.

And ovir that his cote-armure.

As white as is the lilly-floure.

In which he would debate.

His shelde was all of gold so redde

And thereon was a boris hedde;

A carboncle beside.

* * * * * *

His jambeux were of cure bulyb;

His swordis shethe of ivory;

His helm of laton bright;

His sadell was of ruell bonec;

His bridle as the sunne yshone.

Or as the moone ylight;

His spere was of the hne cypres.

That bodeth warre, and nothing pece.

The hedde full sharpe igrounded."

Note a. In Dr. Mcyrick's line collection of ancient arms and armour, we see a figure wearing the habergeon of mail over the hauberk of plate. This does not appear to accord with the arrangement of the harness on Chaucer's night; but both modes were no doubt adopted, according to the pleasure of the wearer.

Note b. Cuir bouilli was extensively used in armour. The corselet, or body-armour, superadded to the hauberk, was at first composed of it, and in the term cuirass we have etymological record that it was so employed; and plastron implies a defence of leather, sitting as close to the breast as a plaister. The figure of John of Eltham may be considered to afford a good example of plate and leather-armour intermixed. Du Cange, in his Notes on Joinville, cites a very curious inventory of the armour necessary for a knight, which will be found to corroborate the above remarks: "Premierement, un harnois de jambes covert de cuir comme a esguillettes, ou long de la garnbe jusques au genouïl, et deux attaches large pour son barrueir (breeches), et souleres values (qu. velours?) attaches au gruës (greaves).

"Item. Cuisses et poullains (knee-plates) de cuir, armoiez de Varennes, des armes au chevalier.

"Item, un chausse de mailles par-dessus le harnois de jambes, attachée au braier, comme dit est par-dessus les cuisses (this was, perhaps, the gipon, jupon, or little petticoat of mail), et uns esperons dorez qui sont attachez a une cordelette autour de la jambe, afin que la molette (rowel) ne tourne dessous le pied.

"Item, pans et manchez, qui sont attachez a la cuirie (cuirass, leather corselet) a tous ses esgrappes sur les espaules, et un seursliere (sous cervelliere or camail) sur le pis (breast) avant.

"Item, bracheres a tout le harnois (qu. bracers or straps for the whole harness?) et le han escucon de la banniere sur le col (shield of his banner or arms slung from the neck), couvert de cuir, avec les tonnerres pour les attacher au braier a la cuirie, et sur le bacinet une coiffe de mailles, et un bel orfroy par devant le front qui veut (qu. a circlet ornamented in front with goldsmiths' work; see effigy of William de Valence).

"Item, bracellets attachez aux espaules de la cuirie (qu. brassarts, arm-plates, fastened to the cuirass at the shoulders?)

"Item, un gaigne pain pour mettre es mains du chevalier (a sword for the knight's hand, here called by a nickname in general use, a 'bread-earner').

"Item, un heaume et le tymbre (crest), tel comme ll voudra.

"Item, deux chains a attachier a la poitrine de la cuirie, une pour Tepee, Tautrepour le baston, en deux vigeres, pour le heaume attacher. (Two chains; one to fasten the sword to the breast of the cuirass, another having some contrivance of a stick to attach the helmet in the same way.)

Note c. Ruell-bone; bone or stained with divers colours.

Note d. The following passage of Froissart will afford an idea of the power of a sharp-ground lance: "Among the Cambresians was a young squire from Gascony, called William Marchant, who came to the held of battle mounted on a good steed, his shield hanging to his neck, his lance in its rest, completely armed, and spurring on to the combat. When Sir Giles Manny saw him approach, he spurred on to meet him most vigorously, and they met, lance in hand, without fear of each other. Sir Giles had his shield pierced through, as well as all the armour near his heart, and the iron passed quite through his body."—Johnes's Translation, 8vo, vol. 1. p. 169.

Towards the latter end of the fifteenth century, the surcoat appears to have been often laid aside for the purpose of exhibiting the effulgence of the polished steel. The armour then was elaborately fluted and channelled; and lastly engraved with various ornaments, legends, and devices. A kind of armour of German manufacture was, we believe, at this period much esteemed, which went under the general name of "Almayne Rivetta."

Note a. The term, therefore, we think has been used in too limited a sense, in describing the armour of Sir John Pechy, or Peche. A passage in Halls Chronicle shows that it was applicable to the whole suit of armour. "The King (Henry VIII.) was received into a bote covered with arras, and so was set on londe. He was appareilled in Almayne Ryvet, crested, and his vanbrace of the same, and on his head a chapeau montabyn, with a rich coronal; ye folde of the chapeau was lined with crymsen saten, and on it a rich brooch, with the image of Sainct George. Over his he had a garment of white cloth of gold, with a red crosse, and so he was received with procession."—Halls Chronicle, re-print, p. 538.

On the subject of plate and mail armour, Mr. Stothard himself makes the following remarks, in a letter addressed to that eminent antiquary, the late Rev. Thomas Kerrich: "It is, I believe, a most difficult thing to say when plate-armour was first introduced, because no representations, however well executed, can tell us of what was worn out of sight, and inventories of armour, as well as notices of writers on the subject, are not common; the only things by which we can gain information. Daniel, in his 'Military Discipline of France' cites a poet who describes a combat between William de Barres and Richard Coeur de Lion (then Earl of Poitou), in which he says, that they met so fiercely that their lances pierced through each other's coat of mail and gambeson, but were resisted by a plate of wrought-iron worn beneath. This is a very solitary piece of information; and the poet cited (whose name, I believe, is not mentioned) might not have been contemporary with the event described, and of course gave the custom of his own time. It however strikes me, that plate was at all times partially used. We find in the reign of Henry the Third pieces of plate on the elbows and knees. I have a drawing from a figure about the time of Edward the First, in mail, with gauntlets of plate; and I strongly suspect that a steel cap was worn under the mail oftener than we imagine. How can we otherwise account for the form in the mail chaperon of William Longespee? Would not the top of the head be round instead of flat, if something were not interposed to give it this form? And how ill calculated to receive a blow, supposing nothing but the mail and linen coif interposed. See the effigy in No. 8. of my work, from Hitchendon churcha: where a piece of mail appears cut out, does it not seem that there is a cap beneath the mail?

Note a. The effigy of Richard Wellesburne de Montfort.

"But, to dwell longer on this head, plate-armour appears, from our paintings in MSS. and monuments, not to have gained any ground till the fifth or sixth of Edward the Third. John of Eltham and the Knight at Ifield, with Sir John Dabernoun, are the first specimens. Yet to show how careful we should be on this point, we find, in an account taken 1313, the sixth of Edward II. of the armour which belonged to Piers Gaveston, the following items: 'A pair of plates (these covered the body, and most probably were the back and breast plate), rivetted and garnished with silver, with four chains of silver, (see for chains the effigy of the Blanchfront,) covered with red velvet, besanted with gold. Two pair of jambers (armour for the legs) of iron, old and new; two coats of velvet to cover the plates.' All the monumental figures I ever saw, of the time of Edward the Second, have been in mail, as far as I could judge; so that you see I am in some difficulty. I am not surprised that mail was not so much worn after the introduction of plate; considering how the body then became loaded, it was necessary to get rid of something. On the Knight at Ifield, and Sir John Dabernouna, we may see first the thick quilted gambeson, over which is the haubergeon of mail, having above that what I take to be the If there was any plate on the body, it was hidden by the surcoat, which went over all; but there is reason to suspect there was: for, in the profile of the Ash Church Effigy, we see between the lacings of the surcoat that the body is covered with narrow plates. After the introduction of plate-armour the gambeson first disappears; which was followed by the aqueton. The aqueton is seen without the gambeson in Sir Oliver Ingham: it is blue, with gold studs or points.

Note a. See the figures referred to by Mr. Stothard in these observations, delineated in the work.

"Before the general introduction of plate-armour, men seem to have been pretty well loaded; but, as most excesses cure themselves, it became necessary to get rid of something. The hauberk was succeeded by the haubergeon, which was shorter: see the Knight at Tewkesbury. Before the end of the fourteenth century, 1 believe, the mail chausses, or stockings, disappeared from our own monuments. This is difficult to ascertain, because the joints (the only places where the chausses might be seen) were always defended by pieces of mail, called, in some instances, gaussets (gussets).

"It does not seem as if the Black Prince had a steel bark preu, yet I apprehend the lower division of his body is in plate. Perhaps he wears the piece of armour called the pancea. I am inclined to think so from John Lord Montacute's effigy, where there is a contrivance to give more action, and defend the joints of the body-armour; which would be unnecessary if either the upper or lower portions were not of plate, or something similar. You perhaps know that there was a substitute for plate, much in fashion at this period, called cmr or leather boiled and moulded into any form; hard enough, when dry, to resist a sword.

Note a. Pance, ventre. Panchiere; partie de l'armour, destinee a couvrir le ventre.—Glossaire de la Langue Romane. For the term bark preu, we should perhaps read borde preui.e. a strong piece of armour, composed of bars or laminae of iron. The appearance of Montacute's armour about the waist will explain Mr. Stothard's meaning.

"I know nothing more difficult than to distinguish the plates under the surcoat; we must seek information on this point from other sources. The singular appearance on monuments of the earliest sort of mail, I think to be owing to its having been sewed on cloth in particular directions, or else a different mode of representing a complete body. If you take a steel purse, and pull it crossways, the rings will range in the same order, and have the same appearance. There is little doubt of their having been rings, and not circular pieces of platea."

Note a. Memoir, p. 268.

In another letter, Mr. Stothard touches on the same subject:

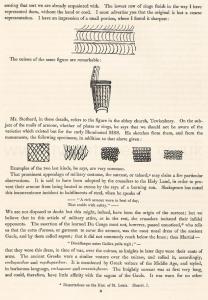

"Amongst other curious things, I have met with a figure which has some remarkable points about it; but for the discovery of these I devoted a whole day in clearing away a thick coating of whitewash, which concealed them. The mail attached to the helmet was of that kind so frequently represented in drawings, and which you have had doubts whether it was not another way of representing that sort we are already acquainted with. The lowest row of rings finish in the way I have represented them, without the band or cord. I must advertise you that the original is but a coarse representation. I have an impression of a small portion, where I found it sharpest:

[See image below for images on the page]

The cuisses of the same figure are remarkable:

[Image]

Mr. Stothard, in these details, refers to the figure in the abbey church, Tewkesbury. On the subject of the mails of armour, whether of plates or rings, he says that we should not be aware of the varieties which existed but for the early illuminated MSS. He sketches from them, and from the monuments, the following specimens, in addition to that above given:

[Image]

Examples of the two last kinds, he says, are very common.

That prominent appendage of military costume, the surcoat, or tabarda, may claim a few particular observations. It is said to have been adopted by the crusaders to the Holy Land, in order to prevent their armour from being heated to excess by the rays of a burning sun. Shakspeare has noted this inconvenience incident to habiliments of steel, when he speaks of

- "A rich armour worn in heat of day,

That scalds with safety."-

We are not disposed to doubt but this might, indeed, have been the origin of the surcoat; but we believe that in this article of military attire, as in the rest, the crusaders imitated their infidel opponents. The assertion of the learned Du Cange must not, however, passed unnoticeda, who tells us that the cotte d'armes, or garment to cover the armour, was the most usual dress of the ancient Gauls, and by them called that it did not commonly reach below the knee; thus Martial —

"Dimidiasque nates Gallica palia tegit;" [French straw covers the half-breeds] —

that they wore this dress, in time of war, over the cuirass, as knights in later days wore their coats of arms. The ancient Greeks wore a similar vesture over the cuirass, and called it, accordingly, επιθωρακιδιον and περιθωρακιδιον. It is mentioned by Greek writers of the Middle Age, and styled, in barbarous language, επιλωρικιον and επανοκλιβανον. The knightly surcoat was at first very long, and could, therefore, have little affinity with the sagum of the Gauls. It was worn for no other purpose, perhaps, than that which has been first mentioned; without we add the very probable one, that by its colour, or figured devices, it afforded a ready distinctionb for the individual wearer.

Note a. Dissertations on the Hist, of St. Louis. Dissert. 1.

Note b. Inattention to this use of coat-armour cost an English Baron his life at the battle of Bannockburn, A.D. 1313:

'There was slain Gilbert de Clare, Earle of Glocester, whome the Scottes would gladly have kept for ransome, if they had knowne him; but he had forgotten to put on his coate-of-armes."—Stow's Annales, p. 326, edit. 1592. The distinction afforded by coat-armour caused it to be styled "cognizance."

"Knights in their conisante clad for the nonce."

The countryman's smockfrock, which in the body much resembled the long surcoat of the ancient knight, was called a tabard. Thus Chaucer's ploughman,

"Took his tabarde, and staffe eke.

And on his hedde he set his hatte." Plowman's Tale.

Nicetas thus describes the attire of the Prince of Antioch, a French lord, at a tournament held in honour of the Emperor Manuel Comnenus: "He was mounted on a beautiful horse, whiter than snow, clothed in a coat-of-arms open on both sides, and which fell to his heels — αμπισκομενος κιτωνα διασκιστον ποδηνεκη." For an illustration, see the effigies of Geoffrey Magnaville and of the nameless Templar.

The warriors represented in the Bayeux Tapestry wear no surcoats over their coats of mail; but, after the first crusade, they are common on our historical sculptural memorials. Joinville, in his Life of St. Louis, says: "I remember once the good Lord King (father to the King now on the throne) speaking of the pomp of dress, and the embroidered coats-of-arms, that are now daily common in the armies, I said to the present King, that, when I was in the Holy Land with his father, and in his army, I never saw one single embroidered coat, or ornamented saddle, in possession of the King his father, or any other lord. He answered that he had done wrong in embroidering his arms, and that he had some coats that had cost him eight hundred livres parisisa." At length, the surcoat became an additional defence for the body, and was thickly gamboised, or quilted.

Note a. Johnes's translation of Joinville's Memoirs, 4to, 180/, p. 94. f Ibid. p. 146.

The same author, in the interesting personal narrative of his adventures in the Holy Land, cites a striking instance of the efficacy of a quilted defence for the body: "I luckily found near me a gaubison of coarse cloth, belonging to a Saracen, and turning the slit part inward, I made a sort of shield, which was of much service to me; for I was only wounded by their shots in five places, whereas my horse was hurt in fifteena.

Note a. MS. of the year 1301, cited by Du Cange.

Those whose property did not qualify them to become knights, and wear the distinction of the knightly order, the hauberk of mail, were to supply themselves with a quilted gambeson, or wambais, as a defence:

"Quicumque vero 20 librarum vel amplius habebit de mobilibus, tenebitur habere loricam, vel loricale et capellum ferreum et lanceam. Qui vero minus de 20 libris habebit de mobilibus, tenebitur habere et capellum ferreum et lanceam." [But whosoever shall have 20 pounds or more of movables, must have a belt, or a breastplate and an iron hat and a lance. But he who will have less than 20 pounds of movables, he must have both an iron hat and a lance]

In the inventory of the wearing-apparel of King Louis Hutin, made 1318, he gives us the following items:

"Une cotte gamboisee de cendal blanc (white sarsenet). Deux tunicles et un gamboison des armes de France. Une couverture de gamboisons brodees des armes du roi. Trois paires de couvertures gamboisiees des armes du roi, et unes Indes jazequenees. Un cuisiax gamboisez (a pair of gamboised cuisses). Unes couvertures gamboisees de France et de Navarre."

Mr. Stothard, in reference to the gamboising on monuments, in a letter to the Rev. T. Kerrich, savs: "You recollect the armour on your Paris figures, formed of ribs running longitudinally. I have not only discovered what it is intended to represent, but also lately found (in further proof that my conjecture was right) a knight whose long surcoat, with sleeves in separate pieces, is composed of it; but what puts the matter beyond doubt is the surcoat of Edward the Black Prince, hanging over his tomb. I have lately examined and drawn it. The whole is ribbed in a similar manner; but we soon account for that, having one specimen of the thing before us, when a hundred of the best representations in stone would not have done it. The surcoat of the Black Prince is stuffed with cotton to nearly three quarters of an inch in thickness; and, in order to keep the cotton in its place, longitudinal and narrow divisions were made all over it—in short it is quilted; the divisions being the places where the cotton is sewed down—what, I believe, was called by the French gamboisinga."

Note a. Memoir, p. 267. An example of the gamboised surcoat, clearly defined, will be seen in the effigy of Shurland.

On the use of coats-of-arms by the infidels, the authority of Joinville is very decisive. Speaking of the youthful captives made in war, purchased of contending states in the East, and composing the Sultan's body-guard, he says: "These youths bore the arms of the Sultan, and were calied his Bahairiz. When their beards were grown, the Sultan made them knights; and their emblazonments were, like his, of pure gold, save that, to distinguish them, they added bars of Vermillion, with roses, birds, griffins, or any other difference, as they pleased. They were called the Band of the Hauleca; which signifies the Archers of the King's Guarda."

Note a. Johnes's translation of Joinville's Memoirs, p. 156.

Thus it also appears probable that the metallic colours of heraldry had their rise in the actual use of the precious metals by the infidels, in the gorgeous distinctions assumed by them for their armoura.

Note a. How many distinctive bearings were suggested by garments, arms, or implements, which must have been familiar to the warriors of the crusades: manches, vair, flanches, minever, swords, arbalists, bows, lances, arrows, pheons (barbed heads for missiles), battering-rams, water-budgets, &c.

During the late long-continued war in which this country was engaged, every military man will recollect that many points of foreign military costume were adopted by the officers of the British army. It does not, therefore, appear wonderful that the first crusaders should have imitated the splendid arms in which their enemies were attired, or, to extend the remark, that theywere induced to adopt their light and elegant pointed style of building, in the room of the heavy features to which they themselves had debased the Roman architecture.

In continuation, we now add some of Mr. Stothard's own remarks, on these and correlative points

"Of the surcoat.—John is the first of the Kings of England, we observe, to wear the surcoat over the hauberk. An old French writer tells us Charlemagne had always, in winter, a new surcoat, with sleeves lined with fur, to guard his body and heart from cold.

"The Crest, or Cap of Estate.—On the seals of Edward the Third, made after he had assumed the lilies of France, by quartering them with the leopards of England, we observe for the first time the cap of estate surmounted with the lion, A. D. 1388.

"We do not find by our monuments, or other memorials, that crests were borne in such variety as at present; with but few exceptions, they were originally the heads of beasts or birds, or bunches of feathers. The reared arm bearing the cross, the demi-lion, and many others of the same character, which now abound, are most probably the conceits of the age of Henry the Eighth, when quaint fancies were sought after.

"From the tomb of Richard the Second, and other evidences, it appears he not only impaled the arms of England with those of Edward the Confessor, but also used them on an escutcheon alone, Edward the Confessor having been adopted by Richard as his patron saint. An example of this, and perhaps the best, is to be found over the entrance to Westminster Hall. Edward the Third adopted St. George as his patron saint; and we find on the tomb of that King the arms of England and the cross of St. George alternately enamelled on escutcheons: and it is not improbable that the cross of St. George has been the English badge ever since Edward's timea.* This appears still more likely, when it is considered that Edward the Third founded the Order of the Garter.

Note a. This is a judicious observation of Mr. Stothard; for we find by Matthew Paris that, in the year 1188, the French crusaders were distinguished by red crosses, the English by white, the Flemings by green. We may therefore infer that the red cross was not then one of our national ensigns. "Crucem animosius susceperunt. Provisum est etiam inter eos, ut omnes de regno, Francorum cruces rubeas, de terris regis Anglorum albas, de terra comitis Flandrensis virides haberent cruces." [They took up the cross with courage. It is also provided among them, as all of the kingdom, French red crosses, white the lands of the king of the English, from the land of the Count of Flanders they would have green crosses] Matt. Paris, Hist. Angl. edit. Watts, p. 146.

"Knights being represented cross-legged was certainly allusive to Templars, or Knights of the Holy Voyage; as after Edward the Thirds reign (in which the order was dissolved) we find no monuments in that fashion.

"At the earlier period, when the mail covered the head, it appears not to have been detached from, but to have been one piece with, that which covered the body; but in the early part of the reign of Henry the Third, to which period our earliest effigies belong, we see the mail on the top of the head, and laced or tied above the left ear. Of this description are the effigies of many of the knights in the Temple church [Map], William Longespee, Earl of Salisbury, the Knight in Malvern abbey church, Robert Courthose, &c. An early specimen differs considerably from these, as the mail appears to go over the surcoat, not to have any kind of lacing or fastening much above the ears, nor to be attached to the shirt of mail, as in the former — only, like them, characterized by this flatness.

"The last alteration we find, is the mail as before, but of one entire piece, sometimes with and sometimes without a fillet; but resembling the hood, a part of the civil dress, to be drawn over the head, and thrown back upon the shoulders, at pleasure.

"The basinet was worn in the fourteenth century, and part of the thirteenth, sometimes with or without a vizor, but always finished with other appendages, as vervillesa. The camail, and what was called by the French a hourson, to which may be added a strap, was to attach the whole, by means of a buckle, to the haubergeon, or plates.

Note a. Memoir, p. 335.

"The camail was originally a covering of mail for the head, and was called capmail, the basinet being worn over it; but about 1330 its form was materially altered: it no longer extended as a covering for the head; vervilles or staples, were introduced on the basinet, and the camail fastened outside, by means of these and a lace. We have some few instances, about the period that this change took place, where the ends of the mail, at its junction with the basinet, are left folding over the lacing, and depending on each side in an ornamental form. The camail was often called the barbiere, or the gorgerette, after the changes took place; but as there is more consistency in Froissart, in his descriptions of armour, I have preferred that name by which he invariably distinguishes this appendage to the basinet. The lacing of the helmet to the cervelliere appears to have been first disused in all those monuments of the time of Henry the Fourth, and was never afterwards resumeda.

Note a. Ibid. p. 332.

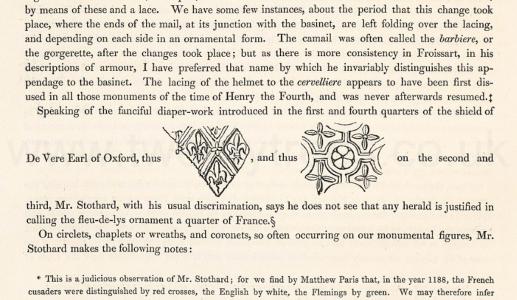

Speaking of the fanciful diaper-work introduced in the first and fourth quarters of the shield of De Vere Earl of Oxford, the [See Image below], and thus [See Image below] on the second and third, Mr. Stothard, with his usual discrimination, says he does not see that any herald is justified in calling the fleu-de-lys ornament a quarter of Francea.

Note a. Ibid. p. 332.

On circlets, chaplets or wreaths, and coronets, so often occurring on our monumental figures, Mr. Stothard makes the following notes:

"The coronet does not appear to have been used, under its present form (excepting it is discovered on the heads of females), by princes, dukes, earls, or knights, till the reign of Edward the Third, and it is then to be found indiscriminately on the heads of all these. We may therefore infer that it was used rather as an than as a particular mark of distinction, as it is to be seen in the monuments on the helmets of simple knights, as well as earls; but it perhaps became so when it disappeared on the helmets of the former, and was retained on those of the latter. The coronet, under the present form, before the introduction of the leaves, was simply a fillet, more or less ornamented, to confine the hair, and was worn alike by all classes above a certain rank. The coronet, under the name of garland, is spoken of by Matthew Parisha In its nearer approach to the modern coronet, it became adorned with precious stones. We have good evidence that in this state it was called a circle. As an ornamented fillet it was probably regarded in the reign of Edward the Third; for Lionel Duke of Clarence in his will leaves two golden circles, with one of which he says he was created a Duke, and with the other his brother Edward was created a Prince. Edmund Earl of March leaves to his daughter Philippa a coronet of gold, with stones, and two hundred great pearls; also a circle, with roses, emeralds, and rubies of Alexandria in the roses.

Note a. Mr. Stothard alludes to the following passage: "Dominus Rex veste deaurata facta de preciosissimo Baldekino, et coronula aurea quse vulgariter dicitur redimitus, sedens gloriose in solio regio jussit,[The Lord King in a gilded garment made of the most precious Baldekin, and the golden crown is commonly called Redeemer, sitting gloriously on the throne commanded the region]" &c. Matt. Parisiensis. in vita Henrici III. edit. Watts, p. 736. This is the part where Henry the Third causes a portion of the blood of Christ, sent to him by the Patriarch and Bishops of Palestine, to be deposited with great ceremony in the abbey church of Westminster, and girds William de Valence, his uterine brother, on the same occasion, with the sword of knighthood.

"The chaplet, in the time of Henry the Fourth, appears to have been worn round the helmet as a defence, being composed of twisted linen, or a fillet of cloth stuffed with somewhat most capable of resisting the blow of a sword. For a specimen of the latter, we must look to Bohun, in Gloucester cathedral."

We shall venture to add a few remarks in continuation of Mr. Stothard's.

The chaplet, and the heraldic wreath placed under the crest, are perhaps nearly the same thing; only that, when the helmet was taken off the wreath was removed to the basinet. The probable origin of the heraldic wreath was the twisted turban of the infidels, called by Joinville a twisted towel, the folds of which he mentions as forming a good defence against the cut of sword or sabre. The pot-helmet of the effigy of a Crusader in the Temple church, seems to be furnished with a plain padded fillet. As the military costume advanced in luxurious splendour, this wreath, chaplet, or circlet, was adorned with rich chasing of goldsmiths' work, precious stones, &c. See a beautiful example in the details of the monument of Sir Edmund de Thorpe.

The knightly wreath, and its protuberant size, is noted by Chaucer. He says it was as thick as the arm:

"A wreth of gold arm gret, of huge weight.

Upon his hed set, ful of stones bright.

Of fine rubys and clere diamants."- The Knight's Tale, 1. 2146.

Froissart relates to us, with his usual interesting circumstantiality, the manner in which Edward the Third presented a chaplet of pearls to the gallant French knight, Sir Eustace de Ribeaumont:

"When supper was over, and the tables removed, the King remained in the hall among the English and French knights bareheaded, except a chaplet of fine pearls which was round his head.

When he came to Sir Eustace de Ribeaumont, he assumed a cheerful look, and said with a smile, 'Sir Eustace, you are the most valiant knight in Christendom, that I ever saw attack his enemy or defend himself I never yet found any one in battle who, body to body, had given me so much to do as you have done this day. I adjudge to you the prize of valour above all the knights of my court, as what is justly due to you. The King then took off the chaplet, which was very rich and handsome, and placing it on the head of Sir Eustace, said, 'Sir Eustace, I present you with this chaplet, as being the best combatant this day, either within or without doors; and I beg of you to wear it this year, for love of me. I know that you are lively and amorous, and love the company of ladies and damsels; therefore say, wherever you go, that I gave it youa'".

Note a. Johnes's Froissart, vol. II. p. 248, 8vo. edit.

These coronets, circlets, or garlands, were at first, perhaps, like the collar of SS. at a later period, a general distinction for gentle rank or honourable achievement. A ram and a ring were constituted the prize for the victor at an ancient wrestling-match. The ring spoken of was, we imagine, a circlet for the head, not for the finger.

"Much worship were it, sothly,

Brothir, unto us all.

Might I the Ram, and als the Ring,

Bringin home to the hall."

Chaucer, The Coke's Tale of Gamelyn.

Chaplets, or garlands, were used at funerals to decorate the corpse or bier of deceased virgins, or suspended in the church where they had attended divine worship. Within our recollection, some, curiously formed of paper, were hanging in Farningham church, in Kent. A writer in the Gentleman's Magazine for June 1747, says, that "in 1733, as the parish-clerk of Bromley, in Kent, was digging a grave in the churchyard, close to the east end of the chancel wall, he dug up a funeral garland, or crown, artificially wrought in filagree-work with gold and silver wire, in resemblance of myrtle. Its leaves were fastened to hoops of larger wire of iron, which were something corroded with rust; but both the gold and silver wire remained very little different from its original splendour. The inside was also lined with cloth of silvera."- The priest at Ophelia's funeral says, she is allowed "her virgin crantsb," or garlands.

Note a. See Dunkin's Outlines of the History of Bromley, in Kent

Note b. Hamlet, Act V. Scene i.

The Monumental Effigies afford many interesting specimens of female habits, and of civil costume in general. Of the wimpled attire of the head, we have examples in the effigies of Aveline Countess of Lancaster, and of the Lady on the brass in Minster church. Chaucer shows us that these headclothes were somewhat weighty: his Wife of Bath,

"Of cloth-making had such a haunta,

She passid them of Ypres or of Gaunt.

* * * * *

Her coverchiefes were large, and fine of ground,

I durst to swere that they weyid three pound,

That on a Sonday were upon her hedde.

Her hosin were of fine scarlet redde.

Full strait ystrained; and her shoos new.

* * * * *

Upon her ambler easily she satte.

All wimpled well, and on her hed a hatte

As brode as is a bokeler or a targe;

A foot mantil about her hippis largeb."

The last line informs us that she wore a mantle down to her feet.

Note a. Such a hoard of manufactured cloths for garments.

Note b. Prologue to the Canterbury Tales.

If we refer to the beautifully illuminated Persian MSS. in the British Museum, we shall be induced to believe the wimple was adopted from the ladies of the East. The coincidence of chain-mail armour in these MSS. with that of our old crusaders, is also very remarkable.

The fret in which the hair was confined forms a remarkable appendage of the coiffure of the women of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It was probably composed of gold or silver wire, and studded with pearls or precious stones. Chaucer will afford us an illustration in the following lines:

To which may be added these:

-"And in his hande a Queene,

And she was clad in roiall habite grene;

A fret of gold she had next her here;

With flourounis small; and, I shall not lie

For all the worlde, right as a daisie

Icrownid is with white levis lite.

So were the flurounis of her crowne white.

For of a perle fine orientall

Her white coroune was imakid all;

For which the white coroune above the grene

Ymade her like a daisie for to sene,

Considerid eke her fret of golde above."

Legende of Good Women, L. 213.

To which may be added these:

-"And everich on her hede

A rich fret of gold, which, withouten drede,

Was full of stately rich stones set;

And every lady had a chapelet."

The Floure and the Leafe, L. 151.

That part of dress worn by women called the kirtle, seems never to have been precisely defined. We believe that it consisted of a sort of close waistcoat without sleeves, to which a petticoat was attached, all in one piecea.

"Full fetis damoselles two

Right yong, and full of semely hede.

In kirtils, and none other wede;

And fair ytressid every tress."

Romaunt of the Rose, L. 776.

Note a. Very similar to this is the dress of the scholars of Christ's Hospital at this day.

The kirtle was worn by men as well as women. Chaucer's spruce parish-clerk is attired in that habit:

"Crulle was his here, and as the gold it shon.

And strouted as a fanne, large and brode;

Full streight and even lay his joly shode;

His rode was red, his eyen grey as goos;

With Poule's windowes corven on his shoesa,

In hosen red, he went ful fetisly.

Yclad he was ful smal and properly.

All in a MWeZ of a light waget,

Ful faire and thicke ben the pointes set;

And therupon he had a gay surplise.

As white as is the blosme upon rise."

Note a. For shoes ornamented in this style, see those of William of Hatfield, Plate 70. Profile view.

Before the introduction of the fret, the hair of females was plaited. See the figure in Scarcliffe church. In the twelfth century, the hair of both males and females were thus disposed in long tresses:

"Then was there flowing hair (fluxus crinium), and extravagant dress; and then was invented the fashion of shoes with curved points. Then the model for young men was to rival women in delicacy of person, to mince their gait, and to walk, with loose gesture, half nakeda.

Note a. Sharpe's translation of William of Malmesbury, p. 336. This passage refers to the reign of William Rulus.

A striking example of this "fluxus crinium," is presented by the figure of Henry the First's Queen (cotemporary with that King's reign), which forms a pilaster to the west door of Rochester cathedral. The figure of the King himself forms another. The Queen's hair depends over either shoulder in long plaits, below her knees. The kings and queens in the curious ancient chess-men of the twelfth century, lately exhibited at the Society of Antiquaries, wear the hair hanging over the shoulders in several long distinct plaits. The west front of the cathedral of St. Denis exhibits a series of the early Kings and Queens of France, with their hair thus disposed. Mrs. Bray has, in her large collection of Mr. C. Stothard's original drawings, his beautiful views of these figures. Ancient as they are, Montfaucon makes them much more so, and calls them, we believe, "Les Rois Merovingiens."

The cote-hardie, like the juste-au-corps, was, we think, a close-bodied vest. Perhaps it derived its name from leaving the neck and bosom bare. Mr. Stothard says, "it was a summer-dress with ladies towards the end of the fourteenth century, and tells the following anecdote in relation to it: 'A certain nobleman had two daughters, but one was fairer then the other. A gallant knight, who had heard the fame of her beauty, asked and obtained her father's leave to woo her. The day was fixed; the knight arrived. When the damsels appeared, the plain sister came dressed in the order of the season; but the fair one, wishing to outvie her, and to show her charms to the best advantage, wore the cote-hardie, which made her so cold, and her nose looked so red and blue, that the knight could not fancy her beauty; so he wooed and wedded the other maid.'

"In the thirty-seventh year of Edward the Third, the wives and daughters of esquires, not possessing the yearly amount of two hundred pounds, are forbidden to wear any purfilling or facings on their garments, or to use any esclaires crinales, or trefles. The wives and daughters of knights, not possessing property to the value of two hundred marks a year, were restricted from using linings of ermine, or latices esclaires, or any kind of precious stones, unless it be upon their heads."

Of the crescent horned head-dress, with its pendant drapery, constructed, no doubt, upon wires, the figure of Beatrice Countess of Arundel, presents an extravagant instance. The same appendage, arranged in better taste, appears on the female in the plate lettered Sir Robert Grushill and his Lady: and it will be observed worn under the hoods of the female mourners round Beauchamp Earl of Warwick's tomb." The mantle appears to have been given only to married women, in the monuments of the time of Henry the Fourtha."

Note a. Memoir, p. 332.

Of the usual Civil Costume of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, excellent examples will be found in the tombs of William of Hatfield, William of Windsor, Blanch dela Tour, and the mourners on the monument of Sir Roger de Kerdeston. One of these mourners, a female, and the figure of the Lady of Sir Miles Stapleton, have long pendant lappets to their sleeves. That of the Judge in Willoughby church [Map], Nottinghamshire, has a tunic to which very full sleeves are attached, and he is girt with a rich ceint, or girdle; an appendage of knights, civilians, and ecclesiastics (when unattired in the sacred vestments), in the fourteenth century.

"Change of clothing every day.

With golden girdles, great an small.'

Plowman's Tale.

There are numerous examples of the Regal Habits in the Monumental Effigies. In those of the royal effigies at Fontevraud we distinguish the tunic, the supertunic or dalmatic, the mantle, the crowns, the boots marked as sandals, the jewelled gloves, &c. We trace the variation in the fashion of these regalia until the time of Henry the Fourth.

The early Episcopal figure in the Temple church shows us the plain low mitre and pastoral staff used by Bishops of that period.

Charles Alfred Stothard (age 33). Engraved by Cooper from a Miniature printed by Alfred Chalon RA in the possession of Mr C Stothard.

The figure of Stratford Archbishop of Canterbury gives a faithful representation of the pontifical habit of a later day; the rich jewelled and more elevated mitre, crocketted with goldsmiths' work; the pall, maniple, chasuble, cope, jewelled gloves, &,c. The costly ornaments of the episcopal office are touched upon in the Plowman's Tale:

"Miters thei werin, mo than two,

Iperlid as the Queene's head;

A staff of golde and pirrie,* lo!

As hevie as it were made of ledde;

With cloth bothe new and redde;

With glitterande gold, as grene as gall."

The mitred Abbot of the Monks of Westminstera is a fine example of the costume of his order. Had Mr. Stothard survived to complete his work, no doubt he would have added to it the habits of other ecclesiastical orders. It is, however, matter of satisfaction that he has left so little unnoticed by his pencil, which could illustrate the progress of our national costume, regal, ecclesiastical, civil, and military.

In closing these prefatory notes, which the antiquarian reader will no doubt amplify from his own store of knowledge, and by examination of the plates (which ever will be found a faithful volume speaking for themselves); it may be acceptable that some short account of the author's life should be addeda.

Note a. Pirrie, for pierrerie, jewelry,

CHARLES ALFRED STOTHARD was the eldest surviving son of Thomas Stothard, Esq. R.A.; he was born July 5th, 1787.

At an early age he exhibited a strong propensity for study, and a genius for drawing. The latter was more particularly developed in various clever miniature scenes which he executed for his schoolboy model of a stage. On leaving school he entered, by his own wish, as a student in the Royal Academy, where he soon attracted notice for the chaste feeling and accuracy with which he drew from the antique sculptures.

In 1802 he accompanied his father to Burleigh, the seat of the Marquis of Exeter, the grand staircase of which the latter was employed in decorating by his masterly pencil. Mr. Stothard senior, suggested to his son that he might fill up his time by making drawings of the monuments in the neighbouring churches, as useful authorities for designing costume. This circumstance gave the first bias of Mr. Charles Stothard's mind towards the subject which afterwards became his pursuit.

In 1808 he received his ticket as student in the Life Academy, and formed a resolution to become an historical painter. Circumstances which subsequently arose, however, changed this determination. Having formed an attachment for the young lady who afterwards became his wife, he feared that as an historical painter he might not acquire sufficient pecuniary independence to enable him prudently to become a married man. He resolved, therefore, to turn his attention exclusively to the illustration of our national antiquities, more particularly in a path which had hitherto been but imperfectly pursued — the delineation of the sculptured Effigies erected in our churches as memorials for the dead, in such manner as they might be referred to and depended on as accurate authorities, illustrating our national history and ancient costume.

In 1810 Mr. Charles Stothard painted a spirited picture, representing the murder of Richard the Second in Pontefract Castle, in which the characteristic dresses of the time were strictly adhered to. For the portrait of the King himself, he made studies Rom his effigy in Westminster Abbey. This picture was exhibited at Somerset Place in 1811.

In the same year he published his first Number of the Monumental Effigies of Great Britain, the objects of which were detailed in the following advertisement, which accompanied the publication:

"It is a circumstance much to be regretted, that so important and interesting a subject as the Monumental Effigies of our Kings, Princes, and Nobles, should have been treated with so much neglect, as among all the works published with the intention of giving representations of them, there is not one that can be relied on. Without possessing that simplicity and chastity which characterizes the originals, they are not correct even as to particulars. It was partly on this account that this Work was undertaken, with a view, by paying the most particular attention to the subject, to rescue from the destroyer Time those Works of Art, introduced into our Cathedrals and Churches as Memorials for the Dead, which, independent of their antiquity, are the greater part specimens of sculpture, which, for grandeur, simplicity, and chastity of style, are not to be surpassed, if equalled, by any nation in Europe.

"There are, though not generally known, as they have never been published, a few Etchings by the Rev. T. Kerrich, of Cambridgea,* Rom Monuments in the Dominicans' and other Churches in Paris, which claim the highest praise that can be bestowed, as well for their accuracy as for the style in which they are executed: these are mentioned as a tribute which they deserve, and as the sight of them induced the proprietor of this Work to execute the Etchings for it himself.

Note a. Some of these etchings were afterwards communicated to the Society of Antiquaries by Mr. Kerrich, and inserted in their Archæologia, vol. XVIII. p. 19A

Had it been but to remedy the above-mentioned defect, there would not, perhaps, have been sufficient encouragement for entering on a Work of this magnitude, till it was found on consideration that other very desirable points would be gained, which would make it more generally interesting. The first of which was the great service these Monumental Effigies would render the Historical Painter, by explaining the costume adopted at different periods in England, as they give more complete ideas on the subject than can be drawn Rom any other source: the knowledge we now have in this respect has been in general gathered from the illuminated MSS. in our public libraries; but either from the minuteness of the figures in some, or the rudeness of the drawing in others that are on a larger scale, they are too much generalized, and do not give us those smaller parts and ornaments which are so interesting.

"The second point gained, was that of elucidating History and Biography, as most of those characters must in the course of this Work be brought in, who have been concerned in the civil and military affairs of England Rom the earliest times to the reign of Henry the Eighth. This has also suggested the idea of illustrating the Historical Plays of our great dramatic poet Shakspeare, in order to assist the stage in selecting its costume with that propriety which will always add consequence to his characters, and give that stamp of truth which they so highly deserve. We should not then see as now the slashed doublet and cloak, peculiar to the sixteenth century, introduced without discrimination in the play of King John as well as that of Henry the Eighth; or the Bastard Faulconbridge in armour, which would puzzle the most profound antiquary to know when or where such was ever worn.

"If it be true that we may derive the above advantages R*om the Monumental Effigies of Great Britain, they surely deserve to be saved from the oblivion in which so many have already sunk, and preserved as records of the splendour with which sculpture once flourished in England."

Mr. Stothard's undertaking procured for him the warm friendship of the Rev. T. Kerrich, of whose talents he makes such honourable mention; and for the candid criticism of that excellent judge of matters of antiquity and art in the progress of his work, he at all times expressed himself much indebteda.

Note a. Mr. Kerrich's numerous and interesting collection of sketches and plans of the details of Gothic Architecture were left, at his death, to the British Museum. His collection of paintings of the Gothic Age were bequeathed to the Society of Antiquaries, and are suspended on the walls of their meeting-room.

The talents of Mr. C. Stothard as an artist, and the accuracy of his research in objects connected with his pursuit, soon obtained for him a distinguished reputation as an antiquary, and the acquaintance of characters eminent for their learning and respectability. Among these were the late Sir Joseph Banks (who highly appreciated him), and Samuel Lysons, Esq. the joint author of "Magna Britannia," who esteemed him as a friend. Mr. Lysons employed him to make some drawings illustrative of his work; far which purpose, in the summer of 1815, Mr. C. Stothard made a journey northward as lar as the Piets' Wall, adding to his portfolio many drawings for the Magna Britannia, monumental subjects for himself, and a number of little sketches, executed in the most delicate and peculiar manner, of different views and buildings in the country through which he passed. During his absence from London Mr. Lysons gave him a proof of his esteem and regard, by obtaining for him, unsolicited, the appointment of Historical Draughtsman to the Society of Antiquaries of London.

In 1816 he was deputed by that body to commence his elaborate and faithful drawings of the famous Tapestry deposited at Bayeux. During his absence in France he visited Chinon, and in the neighbouring Abbey of Fontevraud discovered those interesting Effigies of the Plantagenets, the existence of which after the revolutionary devastation had become doubtful, but which were of high importance to him as subjects for his work. The following account of this matter is given in Mrs. C. Stothard's Tour in Britanny:—"When Mr. Stothard first visited France during the summer of 1816, he came direct to Fontevraud, to ascertain if the Effigies of our early Kings who were buried there yet existed; subjects so interesting to English history were worthy of the inquiry. He found the abbey converted into a prison, and discovered in a cellar belonging to it, the Effigies of Henry the Second and his Queen Eleanor of Guienne, Richard the First, and Isabella of Angouleme, the Queen of John. The chapel where the figures were placed before the revolution had been entirely destroyed, and these valuable Effigies, then removed to the cellar, were subject to continual mutilation from the prisoners, who came twice in every day to draw water from a well. It appeared they had sustained some injury, as Mr. S. found several broken fragments scattered around. He made drawings of the figures; and upon his return to England represented to our Government the propriety of securing such interesting memorials from further destruction. It was deemed advisable, if such a plan could be accomplished, to gain possession of them, that they might be placed with the rest of our Royal Effigies in Westminster Abbeya." An application was accordingly made, which failed; but it had the good effect of drawing the attention of the French authorities towards these remains, and saving them from total destruction. At the same period Mr. Stothard visited the Abbey of L'Espan, near Mans, in search of the effigy of Berengaria, Queen of Richard the First: he found the abbey church converted into a barn, and the object of his inquiry in a mutilated state, concealed under a quantity of wheatb. At Mons he discovered the beautiful enamelled tablet representing Geoffrey Plantagenet. Mr. Stothard's drawings of the Effigies of the English Monarchy extant in France, were, on his return from Fontevraud, submitted by the late Sir George Nayler to the inspection of his late Majesty George the Fourth, who was graciously pleased to express an earnest desire for their publication, and to allow Mr. Stothard to dedicate his Work, the Monumental Effigies, to him. In 1817 he made a second journey to Bayeux for the purpose of continuing his drawings from the Tapestry. In February 1818 he married the young lady to whom he had so long been attached, Anna Eliza (age 27), the only daughter of the late John Kempe, Esq. of the New Kent Road. In July following she accompanied him in his third expedition to France, which he made with a view of completing the Bayeux Tapestry.

His task being accomplished, he proceeded with Mrs. Stothard on a tour of investigation through Normandy, and more particularly Britanny. In order to render their families participators in some degree of the pleasure of their journey, Mrs. Stothard addressed to her mother, Mrs. Kempe, a particular detail of it in a series of letters, which her husband illustrated by various beautiful drawings of the views, costume, and architectural antiquities, which they thought worthy of notice in their route: these formed the ground-work of the publication of Letters to which we have referred.

Note a. Tour in Britanny, p. 294.

Note b. See Memoir of his Life, pp. 243 to 248.

In 1819 Mr. C. Stothard laid before the Society of Antiquaries the complete series of his Drawings horn the Tapestry of Bayeux; and a paper highly creditable to his discrimination, in which he proved from internal evidence, that the Tapestry was coeval with the period immediately succeeding the Conquest, refuting the assertions of the Abbe de la Rue. This Essay was printed in vol. xix. of the Archæologia. On the 2d of July of the same year Mr. Stothard was unanimously elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. In the following autumn he made a series of exquisitely finished drawings for the Society, from the paintings then lately discovered on the walls of the Painted Chamber in the ancient royal palace of Westminster. Fearlessly ardent in his pursuit, he took his stand on the highest and most dangerous parts of the scaffold erected for the repairs; and on one occasion there, narrowly escaped the fate which afterwards befel him. The Society of Antiquaries are in possession of these admirable drawings; and they will, doubtless, when it shall be practicable, be carefully engraved for one of their annual publications.

Some characteristic anecdotes of the ardour of Mr. Charles Stothard in his antiquarian pursuits may find admission here.

The monument of Aveline Countess of Lancaster, in Westminster Abbey, was concealed by the lofty cenotaph of Lord Ligonier, and thus rendered inaccessible to the tight of day. Never daunted by any difficulties which offered themselves to an antiquarian pursuit, Mr. Stothard furnished his pockets with wax-candles, clay, and a percussion tube (a German invention for producing fire). Thus prepared, he watched his opportunity, scaled the monument of Lord Ligonier, lit and fixed his candles, and in the situation above described, smothered with dust, actually completed the drawing of the beautiful monument which embellishes his series of Effigies, without the knowledge of any of the attendants in the abbey.

In one of his customary rambles with the writer, he had the good fortune to meet with the monument of Sir John Peche, or Pechy, as the name is pronounced, at the site of an old baronial mansion, Lullingstone Castle, near Eynsford, in Kent. The effigy afforded a fine specimen of the military costume of the age of Henry the Eighth. The whole was in admirable preservation; but the very circumstance which had contributed to that perfect state, rendered it almost impossible for an artist to gain such an entire view as might enable him to draw it correctly; it was covered by an horizontal slab, distant not more than eighteen inches from the face. (See the Vignette.) This difficulty did not repulse Mr. Stothard. By the aid of a graduated line (he drew all his monuments by scale), he brought all the parts into their due relative proportion, and in two days produced the drawing of which the late Mr. Bartholomew Howlett made a very satisfactory etching, after Mr. Stothard's death, for this work.