Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1854 V1 Pages 233-238

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1854 V1 Pages 233-238 is in Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1854 V1.

Boyton Church [Map], in the Vale of Wylye.

One primary object of the Wilts Archeological Society was declared at their inaugural meeting, to be, the notice of Parochial Churches, the history or architecture of which, might illustrate either our national or local history, or provide subjects for the researches of the student or amateur of Ecclesiastical Architecture. The Parish Church of Boyton seems to afford considerable data for both these laudable purposes; and the following memoir, partly gleaned from the labours of others, and partly the fruit of personal knowledge and observation, is submitted to the Society, with the hope that it may be followed by papers of deeper research, and more engrossing interest.

In a quiet and retired corner of the Vale of Wylye stands the ancient Church of St. Mary, Boyton. It shows in the clearest characters the riches and nobility of the former owners of the soil and Patrons of the Church, as well as the miserable neglect and wretched taste of the later days of the English Church. The dimensions of the Church are as follows:— Chancel.... 38 feet 6 inches by 19 feet. Nave. 49 feet, by 19 feet. North Chapel 13 x 18 feet, South Chapel 26 x 18 feet, Tower 10 feet 6 inches by 11 feet.

The general plan is a Latin Cross, the two side Chapels forming the arms.

The entrance is somewhat singular, being through the Tower which is placed on the North side, with an ancient Vestry forming a lean-to on the West side of the Tower.

The materials of which the Church is generally built, consists of stone and flints in rough courses, and no better testimony can be given to the stability of such construction, than the fact that the Tower facing due North, and of considerable height, has remained from the reign of Henry III. to the present time as perfect as on the first day of its dedication.

The entrance under the Tower is through a remarkably fine Early English doorway. It has a sharp pointed Segmental Arch, without any drip-stone. The archway itself is composed of three orders. The first consists of a plain chamfered continuous Impost.

The architrave is of the second order, and has a hollow between two rounds, with dog-tooth moulding in the hollow; the Impost is banded with a plain chamfer below.

The Arch of the third order has the architrave square.

The inner walls of the Tower are of extremely perfect: flint masonry, without a sympton of crack or decay, and demonstrate the admirable settings, which to this day retain such small masses as the flints without any crumblings of the wall.

A very ancient ladder of the rudest materials leads to the Belfry, which is situated in the upper part of the Tower, and is of considerably later date than the lower stages of the Tower.

On the right hand an ancient Vestry or Priest’s chamber is situated against the West wall, and contains a small aumbrye, probably for relics, and a fire-place of Early English stamp; two small lancet windows seem also to mark this singular chamber as of Early English construction.

Passing into the Nave our attention is arrested by the richness of the work of past generations, and the neglect or want of taste of more recent times.—Thus we observe the massive effigy of a Crusader, and the once richly adorned chantry erected by his descendants, for the benefit of the souls of the departed; whilst the eye is painfully impressed with a flat plaster ceiling, unseemly for a meeting house—much more for the Parish Church of the lordly Giffards: a hideous gallery shuts out the West window, or rather the remains of what once was a handsome perpendicular window, but now gapes without mullion or tracery in naked ugliness. The Nave once was of ample proportion both in height and width. The West end contained (as we have observed) a handsome perpendicular window, under which a square-headed doorway still existing, by its Lioncels, attests the dignity of the Baronial Family to which the Parish and the patronage of the Church belonged.

At the West end of the Church the ancient Norman Pilaster Buttresses may be observed, which, doubtless belonged to the original Church which was restored in Early English times.

The roof of the Nave seems to press upon the head of the visitant, and with its broad plain of whitewash, and hideous uniformity to tell of the days which Bishop Butler witnessed when he wrote as follows:— "Unless the good spirit of building, repairing, and adorning Churches prevails a great deal more amongst us, and be more encouraged, an hundred years will bring a huge number of these sacred fabrics to the ground."

The Chancel Arch is cut off by this roof, and the whole proportions of the Nave are utterly disfigured. The Pews of decayed materials—of various heights and shapes, all tell the same tale of bad taste, and penury towards God, which we trust ere long will be remedied, and that under these better days for the Church, this ancient Temple of God will be made somewhat worthy of its holy purpose.

Projecting from the Nave North and South are two Chapels. That to the South is replete with objects of interest to the historian and the architect. Two small Early English Arches open into this Chantry, which from its foundation has belonged to the Lords of the Manor of Boyton.

The Archways consist of two orders of pointed Segmental Arches. The Arch of the first order has on the Chantry side a plain chamfered edge; that of the second order consists of a hollow round and a quarter round, with a square edged soffit. These Arches spring from a simple pier and two responds. The capitals are well shaped and very bold in character, exactly similar to several specimens in Salisbury Cathedral; the responds are finished with two engaged half columns, answering in size and proportion to the clear columns of the Pier; the Bases consist of two rolls, and a roll faced with a fillet on a circular plinth.

In the wall is to be observed the remains of the roodloft staircase and passage—the staples for the hinges yet remaining in the wall.

The Chapel into which we have now entered is by far the most interesting part of this ancient Church. The features of the building remarkably illustrate the transition from Early English to Decorated Architecture; and the monumental remains exactly confirm by the probable history of the dead, the dates to which the building is to be attributed. The distinguishing points of the building into which we have now entered may be described as consisting of two windows of very striking and original construction, three sedilia and two tombs, one containing an effigy in very good preservation, the other being a coffin tomb of small size but of great richness.

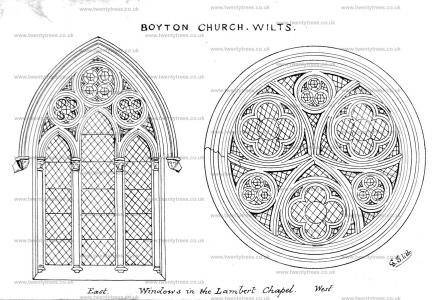

We will describe first the windows.

That to the East consists of a three-light window, in which we see the marks of Early English Architecture departing, and Decorated entering into the architect’s mind; the head of the window is composed of circles in compartments, which partake far more of the Decorated style, whilst the mullions and arches of the windows are of Early English formation. The centre light is higher than the side openings; the width of the centre is 2ft., that of the side light 1ft. 8in. each. The foliage of the capitals is very rich, and is of completely Segmental English character; so is the profile of the Bases which have the vertical hollow distinctive of that style. At the further, or West end of this Chapel the corresponding window is of singular construction, size, and beauty. It is completely round, and the same struggle between the two styles of Early English, and Decorated, is to be observed here.

The window is 12ft. in diameter. The mouldings and mullions make up three Segmental triangles, with three intermediate compartments. Each of these triangles contains a circle, and the foliation of this circle appears to be formed by piercing circles which break into each other. The four circular apertures surround a centre, which cuts into them, all forming a complete quatrefoil. The only two instances recorded of an exactly similar construction are in Lausanne and Modena Cathedrals. The compartments between the triangles also contain circles in threes; a plain outer band containing the three rings as it were within alarger ring. This window contains a few broken remains of Early English quarried glass, and seems to invite restoration by its noble proportions and massive yet symmetrical arrangement.

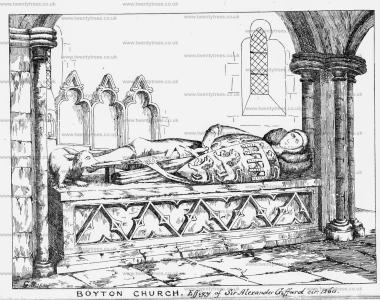

Beneath the Easternmost of the Arches dividing the Chapel from the Nave [Map] is an altar tomb, the one side being composed of slightly pointed Arches, the other of a series of triangles; upon the tomb reposes the effigy of a Knight clad in chain armour, the legs crossed, and the feet resting upon an animal, which, may be eithera wild cat or a lion.—Upon his left arm is the triangular shield of the 13th century; his right arm extending across his breast grasps the long straight sword, which doubtless in its reality had cloven many an infidel’s crest. The figure is of a man in full vigour, of ordinary size, and good proportion. His shield carries the arms of Giffard, gules, three-lions. passant or; in chief, a label of five points azure; upon each point, two Fleur-de-lis of the second. This beyond all doubt is the effigy of Alexander Giffard, the Crusader mentioned in Matthew Paris, as we shall hereafter show.

In the centre of the Chapel there stands a small altar tomb of later and richer work than any portion of the Chapel.—It appears to have contained the body of a female, or child of high rank—the tomb is hollowed to form a coffin, 4ft. 11in. in length.

The tomb would appear to be of the date of Edward III. and may very probably have contained the body of the last of the lordly Giffards, the Lady Margaret, whose death would coincide with the style of this tomb. The sides of this tomb are adorned with canopied niches, from which the figures, probably of alabaster, have been removed.

In the Chapel remain three sedilia and a piscina, still presenting the same mixture of Early English and Decorated Architecture, which pervades this part of the Church.

Returning into the body of the Church—we have to mention a North Chapel of Decorated structure, the North window is of three lights, with purely Decorated tracery above; there is asmall niche in the Eastern side of the Arch which separates the Chapel from the Nave. A very magnificent slab of Purbeck Marble formed part of the floor of this Chapel, and contained the matrix of a very superb brass, which seems to have been of a warrior, and from the canopy work the probable date would be of the reign of Edward II., or a little later. On removing this stone in the summer of 1853, for some repairs, a stone coffin was found, formed not of single but of several stones, and a skeleton nearly perfect, with the skull placed on one side of the body, as though the body had been decapitated.

It is hardly a rash conjecture that this Chapel was erected for the interment of the last male Giffard, who joining in the rebellion of Thomas Earl of Lancaster, in the reign of Edward II. was beheaded at Gloucester, and that the decapitated skeleton was that of the unfortunate Baron himself.

We now finish our survey with the Chancel.

This part of the Church partakes of the Early English style in its older portions, and of Perpendicular in the later features.

Three sections of the South side of the Altar are of Early English work, and in good preservation; the side windows are three small and very simple lancet windows on the North, and two on the South side.

In the window nearest the Altar are the arms of Giffard, in very ancient glass, and very perfect.

The East window is of Perpendicular construction, presenting no very remarkable features, but yet of good shape, and with graceful tracery in the upper part.

Two orifices in the Eastern wall were discovered by an ingenious antiquary, to whom the writer is largely indebted for information, - the Rev. G. Southwell, Vicar of Yetminster.

The Southern orifice formed an aumbrye, the other probably the Credence Table.

Such is a general outline of a Church once singularly rich and beautiful in its arrangements and general outline; but which from many combined causes has been allowed either to fall into decay, or when repaired, has been handled in a manner that makes the bystanders almost regret the reparation, but which we trust ere long will be restored to its former completeness and beauty.

Arthur Fane.