Shakespeare's Plays

Shakespeare's Plays is in Plays.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Two Gentlemen of Verona

Two Gentlemen of Verona Act Five

Two Gentlemen of Verona Act Five Scene 4

Valentine. Thou common friend, that's without faith or love,

For such is a friend now. Treacherous man,

Thou hast beguiled my hopes; nought but mine eye

Could have persuaded me. Now I dare not say

I have one friend alive; thou wouldst disprove me.

Who should be trusted when one's right hand

Is perjured to the bosom? Proteus,

I am sorry I must never trust thee more,

But count the world a stranger for thy sake.

The private wound is deepest. O, time most accursed,

'Mongst all foes that a friend should be the worst!

Proteus. My shame and guilt confounds me.

Forgive me, Valentine. If hearty sorrow

Be a sufficient ransom for offense,

I tender 't here. I do as truly suffer

As e'er I did commit.

1851. William Holman Hunt (age 23). "Valentine rescuing Sylvia from Proteus". Two Gentlemen of Verona Act Five Scene 4.

1851. William Holman Hunt (age 23). "Valentine rescuing Sylvia from Proteus". Two Gentlemen of Verona Act Five Scene 4.

Proteus: Two Gentlemen of Verona Act Five Scene 4. Proteus. Valentine!

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Richard II

Richard II Act 3

Richard II Act 3 Scene 3

Synopsis: Bolingbroke, approaching Flint Castle [Map], learns that Richard is within. In answer to Bolingbroke’s trumpets, Richard and Aumerle appear on the battlements. Northumberland presents Bolingbroke’s demand that Richard yield Bolingbroke’s "lineal royalties" and lift the sentence of banishment. Richard agrees. Northumberland returns and asks that Richard descend to Bolingbroke, who awaits him in the outer court. The cousins meet and Richard expresses willingness to yield to Bolingbroke and accompany him to London.

[Enter with Drum and Colors Bolingbroke, York, Northumberland, with Soldiers and Attendants].

BOLINGBROKE.

So that by this intelligence we learn

The Welshmen are dispersed, and Salisbury

Is gone to meet the King, who lately landed

With some few private friends upon this coast.

NORTHUMBERLAND.

The news is very fair and good, my lord:

Richard not far from hence hath hid his head.

YORK.

It would beseem the Lord Northumberland

To say "King Richard." Alack the heavy day

When such a sacred king should hide his head!

NORTHUMBERLAND.

Your Grace mistakes; only to be brief

Left I his title out.

YORK.

The time hath been, would you have been so brief with him,

He would have been so brief to shorten you,

For taking so the head, your whole head’s length.

BOLINGBROKE.

Mistake not, uncle, further than you should.

YORK.

Take not, good cousin, further than you should,

Lest you mistake. The heavens are over our heads.

BOLINGBROKE.

I know it, uncle, and oppose not myself

Against their will. But who comes here?

[Enter Percy]

Welcome, Harry. What, will not this castle yield?

PERCY.

The castle royally is manned, my lord,

Against thy entrance.

BOLINGBROKE.

Royally? Why, it contains no king.

PERCY. Yes, my good lord,

It doth contain a king. King Richard lies

Within the limits of yon lime and stone,

And with him are the Lord Aumerle, Lord Salisbury,

Sir Stephen Scroop, besides a clergyman

Of holy reverence—who, I cannot learn.

NORTHUMBERLAND.

O, belike it is the Bishop of Carlisle.

BOLINGBROKE., [to Northumberland] Noble lord,

Go to the rude ribs of that ancient castle,

Through brazen trumpet send the breath of parley

Into his ruined ears, and thus deliver:

Henry Bolingbroke

On both his knees doth kiss King Richard’s hand

And sends allegiance and true faith of heart

To his most royal person, hither come

Even at his feet to lay my arms and power,

Provided that my banishment repealed

And lands restored again be freely granted.

If not, I’ll use the advantage of my power

And lay the summer’s dust with showers of blood

Rained from the wounds of slaughtered Englishmen—

The which how far off from the mind of Bolingbroke

It is such crimson tempest should bedrench

The fresh green lap of fair King Richard’s land,

My stooping duty tenderly shall show.

Go signify as much while here we march

Upon the grassy carpet of this plain.

[Northumberland and Trumpets approach the battlements.]

Let’s march without the noise of threat’ning drum,

That from this castle’s tottered battlements

Our fair appointments may be well perused.

Methinks King Richard and myself should meet

With no less terror than the elements

Of fire and water when their thund’ring shock

At meeting tears the cloudy cheeks of heaven.

Be he the fire, I’ll be the yielding water;

The rage be his, whilst on the earth I rain

My waters—on the earth and not on him.

March on, and mark King Richard how he looks.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Richard III

Richard III was written around 1592-1594 by William Shakespeare.

Richard III Act 1

Richard III Act 1 Scene 4

Richard III Act 1 Scene 4 Lines 1 to 77

[Enter Clarence and Keeper]

KEEPER. Why looks your Grace so heavily today?

CLARENCE. O, I have passed a miserable night, So full of fearful dreams, of ugly sights, That, as I am a Christian faithful man, I would not spend another such a night Though 'twere to buy a world of happy days, So full of dismal terror was the time.

KEEPER. What was your dream, my lord? I pray you tell me.

CLARENCE. Methoughts that I had broken from the Tower, And was embark'd to cross to Burgundy; And, in my company, my brother Gloucester; Who from my cabin tempted me to walk Upon the hatches: thence we looked toward England, And cited up a thousand fearful times, During the wars of York and Lancaster That had befall'n us. As we paced along Upon the giddy footing of the hatches, Methought that Gloucester stumbled; and, in falling, Struck me, that thought to stay him, overboard, Into the tumbling billows of the main. Lord, Lord! methought, what pain it was to drown! What dreadful noise of waters in mine ears! What ugly sights of death within mine eyes! Methought I saw a thousand fearful wrecks; Ten thousand men that fishes gnaw'd upon; Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl, Inestimable stones, unvalued jewels, All scatter'd in the bottom of the sea: Some lay in dead men's skulls; and, in those holes Where eyes did once inhabit, there were crept, As 'twere in scorn of eyes, reflecting gems, Which woo'd the slimy bottom of the deep, And mock'd the dead bones that lay scatter'd by.

KEEPER. Had you such leisure in the time of death To gaze upon these secrets of the deep?

CLARENCE. Methought I had, and often did I strive To yield the ghost, but still the envious flood Stopped in my soul and would not let it forth To find the empty, vast, and wand'ring air, But smothered it within my panting bulk, Who almost burst to belch it in the sea.

KEEPER. Awaked you not in this sore agony?

CLARENCE. No, no, my dream was lengthened after life. O, then began the tempest to my soul. I passed, methought, the melancholy flood, With that sour ferryman which poets write of, Unto the kingdom of perpetual night. The first that there did greet my stranger-soul Was my great father-in-law, renownèd Warwick, Who spake aloud "What scourge for perjury Can this dark monarchy afford false Clarence?" And so he vanished. Then came wand'ring by A shadow like an angel, with bright hair Dabbled in blood, and he shrieked out aloud "Clarence is come-false, fleeting, perjured Clarence, That stabbed me in the field by Tewkesbury. Seize on him, furies. Take him unto torment." With that, methoughts, a legion of foul fiends Environed me and howlèd in mine ears Such hideous cries that with the very noise I trembling waked, and for a season after Could not believe but that I was in hell, Such terrible impression made my dream.

KEEPER. No marvel, lord, though it affrighted you. I am afraid, methinks, to hear you tell it.

CLARENCE. Ah keeper, keeper, I have done these things, That now give evidence against my soul, For Edward's sake, and see how he requites me.-O God, if my deep prayers cannot appease thee, But thou wilt be avenged on my misdeeds, Yet execute thy wrath in me alone! O, spare my guiltless wife and my poor children!-Keeper, I prithee sit by me awhile. My soul is heavy, and I fain would sleep.

KEEPER. I will, my lord. God give your Grace good rest.

[Clarence Sleeps].

Richard III Act 1 Scene 4 Lines 78 to 85

[Enter Brakenbury the Lieutenant].

BRAKENBURY. Sorrow breaks seasons and reposing hours, Makes the night morning, and the noontide night. Princes have but their titles for their glories, An outward honor for an inward toil, And, for unfelt imaginations, They often feel a world of restless cares, So that between their titles and low name There's nothing differs but the outward fame.

Richard III A1S4 86 166

[Enter two Murderers].

BRAKENBURY. What wouldst thou, fellow? And how cam'st thou hither?

SECOND MURDERER I would speak with Clarence, and I came hither on my legs.

BRAKENBURY What, so brief?

FIRST MURDERER 'Tis better, sir, than to be tedious. Let him see our commission, and talk no more.

[Brakenbury reads the commission.]

BRAKENBURY. I am in this commanded to deliver The noble Duke of Clarence to your hands. I will not reason what is meant hereby Because I will be guiltless from the meaning. There lies the Duke asleep, and there the keys. He hands them keys. I'll to the King and signify to him That thus I have resigned to you my charge.

FIRST MURDERER You may, sir. 'Tis a point of wisdom. Fare you well.

[Brakenbury and the Keeper exit].

SECOND MURDERER What, shall I stab him as he sleeps?

FIRST MURDERER No. He'll say 'twas done cowardly, when he wakes.

SECOND MURDERER Why, he shall never wake until the great Judgment Day.

FIRST MURDERER Why, then he'll say we stabbed him sleeping.

SECOND MURDERER The urging of that word "judgment" hath bred a kind of remorse in me.

FIRST MURDERER What, art thou afraid?

SECOND MURDERER Not to kill him, having a warrant, but to be damned for killing him, from the which no warrant can defend me.

FIRST MURDERER I thought thou hadst been resolute.

SECOND MURDERER So I am-to let him live.

FIRST MURDERER I'll back to the Duke of Gloucester and tell him so.

SECOND MURDERER Nay, I prithee stay a little. I hope this passionate humor of mine will change. It was wont to hold me but while one tells twenty.

FIRST MURDERER How dost thou feel thyself now?

SECOND MURDERER Faith, some certain dregs of conscience are yet within me.

FIRST MURDERER Remember our reward when the deed's done.

SECOND MURDERER Zounds, he dies! I had forgot the reward.

FIRST MURDERER Where's thy conscience now?

SECOND MURDERER O, in the Duke of Gloucester's purse.

FIRST MURDERER When he opens his purse to give us our reward, thy conscience flies out.

SECOND MURDERER 'Tis no matter. Let it go. There's few or none will entertain it.

FIRST MURDERER What if it come to thee again?

SECOND MURDERER I'll not meddle with it. It makes a man a coward: a man cannot steal but it accuseth him; a man cannot swear but it checks him; a man cannot lie with his neighbor's wife but it detects him. 'Tis a blushing, shamefaced spirit that mutinies in a man's bosom. It fills a man full of obstacles. It made me once restore a purse of gold that by chance I found. It beggars any man that keeps it. It is turned out of towns and cities for a dangerous thing, and every man that means to live well endeavors to trust to himself and live without it.

FIRST MURDERER Zounds, 'tis even now at my elbow, persuading me not to kill the Duke.

SECOND MURDERER Take the devil in thy mind, and believe him not. He would insinuate with thee but to make thee sigh.

FIRST MURDERER I am strong-framed. He cannot prevail with me.

SECOND MURDERER Spoke like a tall man that respects thy reputation. Come, shall we fall to work?

FIRST MURDERER Take him on the costard with the hilts of thy sword, and then throw him into the malmsey butt in the next room.

SECOND MURDERER O, excellent device-and make a sop of him!

FIRST MURDERER Soft, he wakes.

SECOND MURDERER Strike!

FIRST MURDERER No, we'll reason with him.

Richard III Act 1 Scene 4 Lines 167 to 297

[Clarence wakes].

CLARENCE. Where art thou, keeper? Give me a cup of wine.

SECOND MURDERER. You shall have wine enough, my lord, anon.

CLARENCE. In God's name, what art thou?

FIRST MURDERER A man, as you are.

CLARENCE But not, as I am, royal.

FIRST MURDERER Nor you, as we are, loyal.

CLARENCE Thy voice is thunder, but thy looks are humble.

FIRST MURDERER My voice is now the King's, my looks mine own.

CLARENCE How darkly and how deadly dost thou speak! Your eyes do menace me. Why look you pale? Who sent you hither? Wherefore do you come?

SECOND MURDERER To, to, to-

CLARENCE To murder me?

BOTH Ay, ay.

CLARENCE You scarcely have the hearts to tell me so And therefore cannot have the hearts to do it. Wherein, my friends, have I offended you? FIRST MURDERER Offended us you have not, but the King.

CLARENCE I shall be reconciled to him again.

SECOND MURDERER Never, my lord. Therefore prepare to die.

CLARENCE Are you drawn forth among a world of men To slay the innocent? What is my offense? Where is the evidence that doth accuse me? What lawful quest have given their verdict up Unto the frowning judge? Or who pronounced The bitter sentence of poor Clarence' death Before I be convict by course of law? To threaten me with death is most unlawful. I charge you, as you hope to have redemption, By Christ's dear blood shed for our grievous sins, That you depart, and lay no hands on me. The deed you undertake is damnable.

FIRST MURDERER What we will do, we do upon command.

SECOND MURDERER And he that hath commanded is our king.

CLARENCE Erroneous vassals, the great King of kings Hath in the table of His law commanded That thou shalt do no murder. Will you then Spurn at His edict and fulfill a man's? Take heed, for He holds vengeance in His hand To hurl upon their heads that break His law.

SECOND MURDERER And that same vengeance doth He hurl on thee For false forswearing and for murder too. Thou didst receive the sacrament to fight In quarrel of the House of Lancaster.

FIRST MURDERER And, like a traitor to the name of God, Didst break that vow, and with thy treacherous blade Unrippedst the bowels of thy sovereign's son.

SECOND MURDERER Whom thou wast sworn to cherish and defend.

FIRST MURDERER How canst thou urge God's dreadful law to us When thou hast broke it in such dear degree?

CLARENCE Alas! For whose sake did I that ill deed? For Edward, for my brother, for his sake. He sends you not to murder me for this, For in that sin he is as deep as I. If God will be avengèd for the deed, O, know you yet He doth it publicly! Take not the quarrel from His powerful arm; He needs no indirect or lawless course To cut off those that have offended Him.

FIRST MURDERER Who made thee then a bloody minister When gallant-springing, brave Plantagenet, That princely novice, was struck dead by thee?

CLARENCE My brother's love, the devil, and my rage.

FIRST MURDERER Thy brother's love, our duty, and thy faults Provoke us hither now to slaughter thee.

CLARENCE If you do love my brother, hate not me. I am his brother, and I love him well. If you are hired for meed, go back again, And I will send you to my brother Gloucester, Who shall reward you better for my life Than Edward will for tidings of my death.

SECOND MURDERER You are deceived. Your brother Gloucester hates you.

CLARENCE O no, he loves me, and he holds me dear. Go you to him from me.

FIRST MURDERER Ay, so we will.

CLARENCE Tell him, when that our princely father York Blessed his three sons with his victorious arm, He little thought of this divided friendship. Bid Gloucester think of this, and he will weep.

FIRST MURDERER Ay, millstones, as he lessoned us to weep.

CLARENCE O, do not slander him, for he is kind.

FIRST MURDERER Right, as snow in harvest. Come, you deceive yourself. 'Tis he that sends us to destroy you here.

CLARENCE It cannot be, for he bewept my fortune, And hugged me in his arms, and swore with sobs That he would labor my delivery.

FIRST MURDERER Why, so he doth, when he delivers you From this Earth's thralldom to the joys of heaven.

SECOND MURDERER Make peace with God, for you must die, my lord.

CLARENCE Have you that holy feeling in your souls To counsel me to make my peace with God, And are you yet to your own souls so blind That you will war with God by murd'ring me? O sirs, consider: they that set you on To do this deed will hate you for the deed.

SECOND MURDERER, to First Murderer What shall we do?

CLARENCE Relent, and save your souls. Which of you-if you were a prince's son Being pent from liberty, as I am now-If two such murderers as yourselves came to you, Would not entreat for life? Ay, you would beg, Were you in my distress.

FIRST MURDERER Relent? No. 'Tis cowardly and womanish.

CLARENCE Not to relent is beastly, savage, devilish. To Second Murderer. My friend, I spy some pity in thy looks. O, if thine eye be not a flatterer, Come thou on my side and entreat for me. A begging prince what beggar pities not?

SECOND MURDERER Look behind you, my lord.

FIRST MURDERER Take that, and that. (Stabs him.) If all this will not do, I'll drown you in the malmsey butt within. He exits with the body.

SECOND MURDERER A bloody deed, and desperately dispatched. How fain, like Pilate, would I wash my hands Of this most grievous murder.

[Enter First Murderer]

FIRST MURDERER How now? What mean'st thou that thou help'st me not? By heavens, the Duke shall know how slack you have been.

SECOND MURDERER I would he knew that I had saved his brother. Take thou the fee, and tell him what I say, For I repent me that the Duke is slain.

[He exits].

FIRST MURDERER So do not I. Go, coward as thou art. Well, I'll go hide the body in some hole Till that the Duke give order for his burial. And when I have my meed, I will away, For this will out, and then I must not stay.

[He exits].

Richard III Act 4

Richard III Act 4 Scene 3

Richard III Act 4 Scene 3 Lines 1 to 35

Enter Tyrrel.

TYRREL The tyrannous and bloody act is done,

The most arch deed of piteous massacre

That ever yet this land was guilty of.

Dighton and Forrest, who I did suborn

To do this piece of ruthless butchery,

Albeit they were fleshed villains, bloody dogs,

Melted with tenderness and mild compassion,

Wept like two children in their deaths' sad story.

"O thus," quoth Dighton, "lay the gentle babes."

"Thus, thus," quoth Forrest, "girdling one another

Within their alabaster innocent arms.

Their lips were four red roses on a stalk,

And in their summer beauty kissed each other.

A book of prayers on their pillow lay,

Which once," quoth Forrest, "almost changed my mind,

But, O, the devil-" There the villain stopped;

When Dighton thus told on: "We smotherèd

The most replenishèd sweet work of nature

That from the prime creation e'er she framed."

Hence both are gone with conscience and remorse;

They could not speak; and so I left them both

To bear this tidings to the bloody king.

Enter Richard.

And here he comes.-All health, my sovereign lord.

RICHARD Kind Tyrrel, am I happy in thy news?

TYRREL If to have done the thing you gave in charge

Beget your happiness, be happy then,

For it is done.

RICHARD But did'st thou see them dead?

TYRREL I did, my lord.

RICHARD And buried, gentle Tyrrel?

TYRREL The chaplain of the Tower hath buried them,

But where, to say the truth, I do not know.

RICHARD Come to me, Tyrrel, soon at after-supper,

When thou shalt tell the process of their death.

Meantime, but think how I may do thee good,

And be inheritor of thy desire.

Farewell till then.

TYRREL I humbly take my leave.

Tyrrel exits.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Love's Labour's Lost

Love's Labour's Lost Act 1

Love's Labour's Lost Act 1 Scene 2

ACT 1 SCENE II. The park.

[Enter ARMADO and MOTH.]

ARMADO. Boy, what sign is it when a man of great spirit grows melancholy?

MOTH. A great sign, sir, that he will look sad.

ARMADO. Why, sadness is one and the self-same thing, dear imp.

MOTH. No, no; O Lord, sir, no.

ARMADO. How canst thou part sadness and melancholy, my tender juvenal?

MOTH. By a familiar demonstration of the working, my tough senior.

ARMADO. Why tough senior? Why tough senior?

MOTH. Why tender juvenal? Why tender juvenal?

ARMADO. I spoke it, tender juvenal, as a congruent epitheton appertaining to thy young days, which we may nominate tender.

MOTH. And I, tough senior, as an appertinent title to your old time, which we may name tough.

ARMADO. Pretty and apt.

MOTH. How mean you, sir? I pretty, and my saying apt? or I apt, and my saying pretty?

ARMADO. Thou pretty, because little.

MOTH. Little pretty, because little. Wherefore apt?

ARMADO. And therefore apt, because quick.

MOTH. Speak you this in my praise, master?

ARMADO. In thy condign praise.

MOTH. I will praise an eel with the same praise.

ARMADO. What! That an eel is ingenious?

MOTH. That an eel is quick.

ARMADO. I do say thou art quick in answers: thou heat'st my blood.

MOTH. I am answered, sir.

ARMADO. I love not to be crossed.

MOTH. [Aside] He speaks the mere contrary: crosses love not him.

ARMADO. I have promised to study three years with the duke.

MOTH. You may do it in an hour, sir.

ARMADO. Impossible.

MOTH. How many is one thrice told?

ARMADO. I am ill at reck'ning; it fitteth the spirit of a tapster.

MOTH. You are a gentleman and a gamester, sir.

ARMADO. I confess both: they are both the varnish of a complete man.

MOTH. Then I am sure you know how much the gross sum of deuce-ace amounts to.

ARMADO. It doth amount to one more than two.

MOTH. Which the base vulgar do call three.

ARMADO. True.

MOTH. Why, sir, is this such a piece of study? Now here's three studied ere ye'll thrice wink; and how easy it is to put 'years' to the word 'three,' and study three years in two words, the dancing horse will tell you.

ARMADO. A most fine figure!

MOTH. [Aside] To prove you a cipher.

ARMADO. I will hereupon confess I am in love; and as it is base for a soldier to love, so am I in love with a base wench. If drawing my sword against the humour of affection would deliver me from the reprobate thought of it, I would take Desire prisoner, and ransom him to any French courtier for a new-devised curtsy. I think scorn to sigh: methinks I should out-swear Cupid. Comfort me, boy: what great men have been in love?

MOTH. Hercules, master.

ARMADO. Most sweet Hercules! More authority, dear boy, name more; and, sweet my child, let them be men of good repute and carriage.

MOTH. Samson, master: he was a man of good carriage, great carriage, for he carried the town gates on his back like a porter; and he was in love.

ARMADO. O well-knit Samson! strong-jointed Samson! I do excel thee in my rapier as much as thou didst me in carrying gates. I am in love too. Who was Samson's love, my dear Moth?

MOTH. A woman, master.

ARMADO. Of what complexion?

MOTH. Of all the four, or the three, or the two, or one of the four.

ARMADO. Tell me precisely of what complexion.

MOTH. Of the sea-water green, sir.

ARMADO. Is that one of the four complexions?

MOTH. As I have read, sir; and the best of them too.

ARMADO. Green, indeed, is the colour of lovers; but to have a love of that colour, methinks Samson had small reason for it. He surely affected her for her wit.

MOTH. It was so, sir, for she had a green wit.

ARMADO. My love is most immaculate white and red.

MOTH. Most maculate thoughts, master, are masked under such colours.

ARMADO. Define, define, well-educated infant.

MOTH. My father's wit my mother's tongue assist me!

ARMADO. Sweet invocation of a child; most pretty, and pathetical!

MOTH. If she be made of white and red, Her faults will ne'er be known; For blushing cheeks by faults are bred, And fears by pale white shown. Then if she fear, or be to blame, By this you shall not know, For still her cheeks possess the same Which native she doth owe. A dangerous rhyme, master, against the reason of white and red.

ARMADO. Is there not a ballad, boy, of the King and the Beggar?

MOTH. The world was very guilty of such a ballad some three ages since; but I think now 'tis not to be found; or if it were, it would neither serve for the writing nor the tune.

ARMADO. I will have that subject newly writ o'er, that I may example my digression by some mighty precedent. Boy, I do love that country girl that I took in the park with the rational hind Costard: she deserves well.

MOTH. [Aside] To be whipped; and yet a better love than my master.

ARMADO. Sing, boy: my spirit grows heavy in love.

MOTH. And that's great marvel, loving a light wench.

ARMADO. I say, sing.

MOTH. Forbear till this company be past.

[Enter DULL, COSTARD, and JAQUENETTA.]

DULL. Sir, the Duke's pleasure is, that you keep Costard safe: and you must suffer him to take no delight nor no penance; but a' must fast three days a week. For this damsel, I must keep her at the park; she is allowed for the day-woman. Fare you well.

ARMADO. I do betray myself with blushing. Maid!

JAQUENETTA. Man?

ARMADO. I will visit thee at the lodge.

JAQUENETTA. That's hereby.

ARMADO. I know where it is situate.

JAQUENETTA. Lord, how wise you are!

ARMADO. I will tell thee wonders.

JAQUENETTA. With that face?

ARMADO. I love thee.

JAQUENETTA. So I heard you say.

ARMADO. And so, farewell.

JAQUENETTA. Fair weather after you!

DULL. Come, Jaquenetta, away!

[Exit with JAQUENETTA.]

ARMADO. Villain, thou shalt fast for thy offences ere thou be pardoned.

COSTARD. Well, sir, I hope when I do it I shall do it on a full stomach.

ARMADO. Thou shalt be heavily punished.

COSTARD. I am more bound to you than your fellows, for they are but lightly rewarded.

ARMADO. Take away this villain: shut him up.

MOTH. Come, you transgressing slave: away!

COSTARD. Let me not be pent up, sir: I will fast, being loose.

MOTH. No, sir; that were fast and loose: thou shalt to prison.

COSTARD. Well, if ever I do see the merry days of desolation that I have seen, some shall see-

MOTH. What shall some see?

COSTARD. Nay, nothing, Master Moth, but what they look upon. It is not for prisoners to be too silent in their words, and therefore I will say nothing. I thank God I have as little patience as another man, and therefore I can be quiet.

[Exeunt MOTH and COSTARD.]

ARMADO. I do affect the very ground, which is base, where her shoe, which is baser, guided by her foot, which is basest, doth tread. I shall be forsworn,-which is a great argument of falsehood,-if I love. And how can that be true love which is falsely attempted? Love is a familiar; Love is a devil; there is no evil angel but Love. Yet was Samson so tempted, and he had an excellent strength; yet was Solomon so seduced, and he had a very good wit. Cupid's butt-shaft is too hard for Hercules' club, and therefore too much odds for a Spaniard's rapier. The first and second cause will not serve my turn; the passado he respects not, the duello he regards not; his disgrace is to be called boy, but his glory is to subdue men. Adieu, valour! rust, rapier! be still, drum! for your manager is in love; yea, he loveth. Assist me, some extemporal god of rime, for I am sure I shall turn sonneter. Devise, wit; write, pen; for I am for whole volumes in folio.

[Exit.]

Pepy's Diary. 01 Sep 1668. So to the Fair, and there saw several sights; among others, the mare that tells money1, and many things to admiration; and, among others, come to me, when she was bid to go to him of the company that most loved a pretty wench in a corner. And this did cost me 12d. to the horse, which I had flung him before, and did give me occasion to baiser a mighty belle fille that was in the house that was exceeding plain, but fort belle. At night going home I went to my bookseller's in Duck Lane [Map], and find her weeping in the shop, so as ego could not have any discourse con her nor ask the reason, so departed and took coach home, and taking coach was set on by a wench that was naught, and would have gone along with me to her lodging in Shoe Lane, Fleet Street, but ego did donner her a shilling.. and left her, and home, where after supper, W. Batelier with us, we to bed. This day Mrs. Martin come to see us, and dined with us.

Note 1. This is not the first learned horse of which we read. Shakespeare, "Love's Labour's Lost, act i., SC. 2, mentions "the dancing horse",' and the commentators have added many particulars of Banks's bay horse.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, King Henry IV

Pepy's Diary. 01 Jan 1661. After dinner I took my wife to Whitehall, I sent her to Mrs. Pierces (where we should have dined today), and I to the Privy Seal, where Mr. Moore took out all his money, and he and I went to Mr. Pierces; in our way seeing the Duke of York (age 27) bring his Lady this day to wait upon the Queen, the first time that ever she did since that great business; and the Queen (age 51) is said to receive her now with much respect and love; and there he cast up the fees, and I told the money, by the same token one £100 bag, after I had told it, fell all about the room, and I fear I have lost some of it. That done I left my friends and went to my Lord's, but he being not come in I lodged the money with Mr. Shepley, and bade good night to Mr. Moore, and so returned to Mr. Pierces, and there supped with them, and Mr. Pierce, the purser, and his wife and mine, where we had a calf's head carboned1, but it was raw, we could not eat it, and a good hen. But she is such a slut that I do not love her victualls. After supper I sent them home by coach, and I went to my Lord's and there played till 12 at night at cards at Best with J. Goods and N. Osgood, and then to bed with Mr. Shepley.

Note 1. Meat cut crosswise and broiled was said to be carboned. Falstaff says in "King Henry IV"., Part L, act v., sc. 3, "Well, if Percy be alive, I'll pierce him. If he do come in my way, so; if he do not, if I come in his willingly, let him make a carbonado of me".

Pepy's Diary. 04 Jun 1661. From thence to my Lord Crew's to dinner with him, and had very good discourse about having of young noblemen and gentlemen to think of going to sea, as being as honourable service as the land war. And among other things he told us how, in Queen Elizabeth's time, one young nobleman would wait with a trencher at the back of another till he came to age himself. And witnessed in my young Lord of Kent, that then was, who waited upon my Lord Bedford at table, when a letter came to my Lord Bedford that the Earldom of Kent was fallen to his servant, the young Lord; and so he rose from table, and made him sit down in his place, and took a lower for himself, for so he was by place to sit. From thence to the Theatre [Map] and saw "Harry the 4th", a good play. That done I went over the water and walked over the fields to Southwark, and so home and to my lute. At night to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 29 Aug 1666. To St. James's, and there Sir W. Coventry (age 38) took Sir W. Pen (age 45) and me apart, and read to us his answer to the Generalls' letter to the King (age 36) that he read last night; wherein he is very plain, and states the matter in full defence of himself and of me with him, which he could not avoid; which is a good comfort to me, that I happen to be involved with him in the same cause. And then, speaking of the supplies which have been made to this fleete, more than ever in all kinds to any, even that wherein the Duke of Yorke (age 32) himself was, "Well", says he, "if this will not do, I will say, as Sir J. Falstaffe did to the Prince, 'Tell your father, that if he do not like this let him kill the next Piercy himself,'"1 and so we broke up, and to the Duke (age 32), and there did our usual business. So I to the Parke and there met Creed, and he and I walked to Westminster to the Exchequer, and thence to White Hall talking of Tangier matters and Vernaty's knavery, and so parted, and then I homeward and met Mr. Povy (age 52) in Cheapside, and stopped and talked a good while upon the profits of the place which my Lord Bellasses (age 52) hath made this last year, and what share we are to have of it, but of this all imperfect, and so parted, and I home, and there find Mrs. Mary Batelier, and she dined with us; and thence I took them to Islington [Map], and there eat a custard; and so back to Moorfields [Map], and shewed Batelier, with my wife, "Polichinello", which I like the more I see it; and so home with great content, she being a mighty good-natured, pretty woman, and thence I to the Victualling Office, and there with Mr. Lewes and Willson upon our Victualling matters till ten at night, and so I home and there late writing a letter to Sir W. Coventry (age 38), and so home to supper and to bed. No newes where the Dutch are. We begin to think they will steale through the Channel to meet Beaufort. We think our fleete sayled yesterday, but we have no newes of it.

Note 1. "King Henry IV"., Part I, act v., sc. 4.

Pepy's Diary. 02 Nov 1667. Up, and to the office, where busy all the morning; at noon home, and after dinner my wife and Willett and I to the King's playhouse, and there saw "Henry the Fourth" and contrary to expectation, was pleased in nothing more than in Cartwright's speaking of Falstaffe's speech about "What is Honour?" The house full of Parliament-men, it being holyday with them: and it was observable how a gentleman of good habit, sitting just before us, eating of some fruit in the midst of the play, did drop down as dead, being choked; but with much ado Orange Moll did thrust her finger down his throat, and brought him to life again. After the play, we home, and I busy at the office late, and then home to supper and to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 29 Nov 1667. Waked about seven o'clock this morning with a noise I supposed I heard, near our chamber, of knocking, which, by and by, increased: and I, more awake, could, distinguish it better. I then waked my wife, and both of us wondered at it, and lay so a great while, while that increased, and at last heard it plainer, knocking, as if it were breaking down a window for people to get out; and then removing of stools and chairs; and plainly, by and by, going up and down our stairs. We lay, both of us, afeard; yet I would have rose, but my wife would not let me. Besides, I could not do it without making noise; and we did both conclude that thieves were in the house, but wondered what our people did, whom we thought either killed, or afeard, as we were. Thus we lay till the clock struck eight, and high day. At last, I removed my gown and slippers safely to the other side of the bed over my wife: and there safely rose, and put on my gown and breeches, and then, with a firebrand in my hand, safely opened the door, and saw nor heard any thing. Then (with fear, I confess) went to the maid's chamber-door, and all quiet and safe. Called Jane up, and went down safely, and opened my chamber door, where all well. Then more freely about, and to the kitchen, where the cook-maid up, and all safe. So up again, and when Jane come, and we demanded whether she heard no noise, she said, "yes, and was afeard", but rose with the other maid, and found nothing; but heard a noise in the great stack of chimnies that goes from Sir J. Minnes (age 68) through our house; and so we sent, and their chimnies have been swept this morning, and the noise was that, and nothing else. It is one of the most extraordinary accidents in my life, and gives ground to think of Don Quixote's adventures how people may be surprised, and the more from an accident last night, that our young gibb-cat1 did leap down our stairs from top to bottom, at two leaps, and frighted us, that we could not tell well whether it was the cat or a spirit, and do sometimes think this morning that the house might be haunted. Glad to have this so well over, and indeed really glad in my mind, for I was much afeard, I dressed myself and to the office both forenoon and afternoon, mighty hard putting papers and things in order to my extraordinary satisfaction, and consulting my clerks in many things, who are infinite helps to my memory and reasons of things, and so being weary, and my eyes akeing, having overwrought them to-day reading so much shorthand, I home and there to supper, it being late, and to bed. This morning Sir W. Pen (age 46) and I did walk together a good while, and he tells me that the Houses are not likely to agree after their free conference yesterday, and he fears what may follow.

Note 1. A male cat. "Gib" is a contraction of the Christian name Gilbert (Old French), "Tibert". "I am melancholy as a gib-cat" Shakespeare, I King Henry IV, act i., sc. 3. Gib alone is also used, and a verb made from it-"to gib", or act like a cat.

Pepy's Diary. 07 Jan 1668. Up, weary, about 9 o'clock, and then out by coach to White Hall to attend the Lords of the Treasury about Tangier with Sir Stephen Fox (age 40), and having done with them I away back again home by coach time enough to dispatch some business, and after dinner with Sir W. Pen's (age 46) coach (he being gone before with Sir Prince) to White Hall to wait on the Duke of York (age 34), but I finding him not there, nor the Duke of York (age 34) within, I away by coach to the Nursery, where I never was yet, and there to meet my wife and Mercer and Willet as they promised; but the house did not act to-day; and so I was at a loss for them, and therefore to the other two playhouses into the pit, to gaze up and down, to look for them, and there did by this means, for nothing, see an act in "The Schoole of Compliments" at the Duke of York's (age 34) house, and "Henry the Fourth" at the King's house; but, not finding them, nor liking either of the plays, I took my coach again, and home, and there to my office to do business, and by and by they come home, and had been at the King's house, and saw me, but I could [not] see them, and there I walked with them in the garden awhile, and to sing with Mercer there a little, and so home with her, and taught her a little of my "It is decreed", which I have a mind to have her learn to sing, and she will do it well, and so after supper she went away, and we to bed, and there made amends by sleep for what I wanted last night.

Pepy's Diary. 18 Sep 1668. So to the King's house, and saw a piece of "Henry the Fourth"; at the end of the play, thinking to have gone abroad with Knepp, but it was too late, and she to get her part against to-morrow, in "The Silent Woman", and so I only set her at home, and away home myself, and there to read again and sup with Gibson, and so to bed.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, King Henry VIII Play

Pepy's Diary. 10 Dec 1663. Calling at Wotton's, my shoemaker's, today, he tells me that Sir H. Wright (age 26) is dying; and that Harris is come to the Duke's house again; and of a rare play to be acted this week of Sir William Davenant's (age 57): the story of Henry the Eighth with all his wives.

Pepy's Diary. 22 Dec 1663. After dinner abroad with my wife by coach to Westminster, and set her at Mrs. Hunt's while I about my business, having in our way met with Captain Ferrers luckily to speak to him about my coach, who was going in all haste thither, and I perceive the King (age 33) and Duke (age 30) and all the Court was going to the Duke's playhouse to see "Henry VIII" acted, which is said to be an admirable play.

Pepy's Diary. 24 Dec 1663. Thence straight home, being very cold, but yet well, I thank God, and at home found my wife making mince pies, and by and by comes in Captain Ferrers to see us, and, among other talke, tells us of the goodness of the new play of "Henry VIII", which makes me think [it] long till my time is out; but I hope before I go I shall set myself such a stint as I may not forget myself as I have hitherto done till I was forced for these months last past wholly to forbid myself the seeing of one. He gone I to my office and there late writing and reading, and so home to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 01 Jan 1664. Thence to my uncle Wight's (age 62), where Dr. of---, among others, dined, and his wife, a seeming proud conceited woman, I know not what to make of her, but the Dr's. discourse did please me very well about the disease of the stone, above all things extolling Turpentine, which he told me how it may be taken in pills with great ease. There was brought to table a hot pie made of a swan I sent them yesterday, given me by Mr. Howe, but we did not eat any of it. But my wife and I rose from table, pretending business, and went to the Duke's house, the first play I have been at these six months, according to my last vowe, and here saw the so much cried-up play of "Henry the Eighth"; which, though I went with resolution to like it, is so simple a thing made up of a great many patches, that, besides the shows and processions in it, there is nothing in the world good or well done.

Pepy's Diary. 27 Jan 1664. He being gone my wife and I took coach and to Covent Garden [Map], to buy a maske at the French House, Madame Charett's, for my wife; in the way observing the streete full of coaches at the new play, "The Indian Queene" which for show, they say, exceeds "Henry the Eighth".

Pepy's Diary. 30 Dec 1668. After dinner, my wife and I to the Duke's playhouse, and there did see King Harry the Eighth; and was mightily pleased, better than I ever expected, with the history and shows of it. We happened to sit by Mr. Andrews (age 36), our neighbour, and his wife, who talked so fondly to his little boy.

Letters of the Court of James I 1613 Reverend Thomas Lorkin to Sir Thomas Puckering Baronet 30 Jun 1613. 30 Jun 1613. London. Reverend Thomas Lorkin to Thomas Puckering 1st Baronet (age 21).

My last letters advertised you of what had lately happened concerning Cotton, who yielding himself to the king's clemency, doth nevertheless utterly disavow the book, and constantly denieth to be the author of it. Hereupon, his study hath been searched, and there divers papers found, containing many several pieces of the said book, and (which renders the man more odious) certain relics of the late saints of the gunpowder treason, as one of Digby's fingers, Percy's toe, some other part either of Catesby or Bookwood (whether I well remember not), with the addition of a piece of one of Peter Lambert's ribs, to make up the full mess of them. If the proofs which are against him will not extend to the touching of his life, at least they will serve to work him either misery and affliction enough.

Upon Saturday last, being the 26th of this present, there was found, in the stone gallery at Whitehall, a certain letter, bearing address unto the king, which advertiseth him of a treasonable practice against his majesty's own person, to be put in execution the 4th day of the next month, as he went a-hunting (if the commodity so served), or otherwise, as they should find their opportunity; affirming that divers Catholics had therein joined hands, as finding no other means to relieve themselves in the liberty of their conscience; and how there was one great nobleman about his majesty that could give him further instructions of the particulars. That himself was appointed to have been an actor in it; but, touched with a remorse of dyeing his hands in his prince's blood, moved likewise with the remembrance of some particular favours which his father (saith he) had formerly received from his majesty, he could do no less than give him a general notice and warning of it. But because he instanceth not in any one particular, neither subscribed his name, it is held to be a mere invention to intimidate the king, and to beget some strange jealousies in his head of such as are conversant about him.

The prince is as to-morrow to begin housekeeping at Richmond. Sir David Murray and Sir Robert Car (age 35) have newly procured to be sworn (with Sir James Fullerton (age 50)), gentlemen of the bedchamber. Sir Robert Carey (age 50) hath taken no oath, and remains in the same nature that Sir Thomas Chaloner (age 54) did to the late prince deceased. Sir Arthur Mainwaring (age 33), Varnam, and Sir Edward Lewys (age 53), have at length, with much suit, obtained to be sworn gentlemen of his highness's privy chamber.

The great officers must rest still in a longer expectance, unless this occasion help them. The king (age 47) is desirous to relieve his wants by making estates out of the prince's lands; and having taken the opinion of the best lawyers what course is fittest to be followed, their judgment is, that no good assurance can be made unless the prince himself join likewise in the action. Now, this cannot be done without his council and officers for that purpose; so that it is supposed that some time in Michaelmas term next, before any conveyance be made, certain of these officers, if not all, shall be put again into the possession of their former places.

My Lord of Southampton (age 39) hath lately got licence to make a voyage over the Spa, whither he is either already gone, or means to go very shortly. He pretends to take remedy against I know not what malady; but his greatest sickness is supposed to be a discontentment conceived, that he cannot compass to be made one of the privy council; which, not able to brook here well at home, he will try if he can better digest it abroad.

No longer since than yesterday, while Burbage's company were acting at the Globe the play of Henry VIII, and there shooting off certain chambers in way of triumph, the fire catched and fastened upon the thatch of the house, and there burned so furiously, as it consumed the whole house, all in less than two hours, the people having enough to do to save themselves1.

You have heretofore heard of Widdrington's book2, wherein he maintains against the usurpation of popes, the right of kings in matters temporal. This book hath been undertaken to be confuted by some in France; but the author hath proceeded so far in his confutation against kings' prerogatives, as the Court of Parliament at Paris have censured the book, and given order to have the sentence printed.

It is bruited abroad here, that Sir Thomas Puckering (age 21) is grown a very hot and zealous Catholic. Sir Thomas Badger reports to have heard it very confidently avouched at a great man's table; and I assure you, it is the general opinion, or rather fear, of the most that know you and honour you. How far this may prejudice you, I leave to your wise consideration. I myself rest fully assured to the contrary, and so endeavour to possess others. Your care will be in the mean time to avoid all occasions whereby to increase this suspicion and jealousy.

Note 1. Barbage was Shakspeare's associate. The play was Shakespeare's, and the theatre was the one in which he had achieved his brilliant reputation.

Note 2. Probably that printed at Frankfort in 1613, and entitled "Apologia Card. Bellarmini pro jare principam contra anas ipsins rationes pro Aactoritate Papali Principes deponendi."

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Macbeth

Pepy's Diary. 05 Nov 1664. Up and to the office, where all the morning, at noon to the 'Change [Map], and thence home to dinner, and so with my wife to the Duke's house to a play, "Macbeth", a pretty good play, but admirably acted.

Pepy's Diary. 28 Dec 1666. From hence to the Duke's house, and there saw "Macbeth" most excellently acted, and a most excellent play for variety. I had sent for my wife to meet me there, who did come, and after the play was done, I out so soon to meet her at the other door that I left my cloake in the playhouse, and while I returned to get it, she was gone out and missed me, and with W. Hewer (age 24) away home.

Pepy's Diary. 07 Jan 1667. Thence 'lighting at the Temple [Map] to the ordinary hard by and eat a bit of meat, and then by coach to fetch my wife from her brother's (age 27), and thence to the Duke's house, and saw "Macbeth", which, though I saw it lately, yet appears a most excellent play in all respects, but especially in divertisement, though it be a deep tragedy; which is a strange perfection in a tragedy, it being most proper here, and suitable.

Pepy's Diary. 19 Apr 1667. So to the playhouse, not much company come, which I impute to the heat of the weather, it being very hot. Here we saw "Macbeth"1, which, though I have seen it often, yet is it one of the best plays for a stage, and variety of dancing and musique, that ever I saw.

Note 1. See November 5th, 1664. Downes wrote: "The Tragedy of Macbeth, alter'd by Sir William Davenant (age 61); being drest in all it's finery, as new cloaths, new scenes, machines as flyings for the Witches; with all the singing and dancing in it. The first compos'd by Mr. Lock, the other by Mr. Channell and Mr. Joseph Preist; it being all excellently perform'd, being in the nature of an opera, it recompenc'd double the expence; it proves still a lasting play".

Pepy's Diary. 16 Oct 1667. At noon to Broad Street to Sir G. Carteret (age 57) and Lord Bruncker (age 47), and there dined with them, and thence after dinner with Bruncker to White Hall, where the Duke of York (age 34) is now newly come for this winter, and there did our usual business, which is but little, and so I away to the Duke of York's house, thinking as we appointed, to meet my wife there, but she was not; and more, I was vexed to see Young (who is but a bad actor at best) act Macbeth in the room of Betterton (age 32), who, poor man! is sick: but, Lord! what a prejudice it wrought in me against the whole play, and everybody else agreed in disliking this fellow.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Nov 1667. Thence homeward, and called at Allestry's, the bookseller, who is bookseller to the Royal Society, and there did buy three or four books, and find great variety of French and foreign books. And so home and to dinner, and after dinner with my wife to a play, and the girl-"Macbeth", which we still like mightily, though mighty short of the content we used to have when Betterton (age 32) acted, who is still sick.

Pepy's Diary. 12 Aug 1668. Home to dinner, where Pelting dines with us, and brings some partridges, which is very good meat; and, after dinner, I, and wife, and Mercer, and Deb., to the Duke of York's house, and saw "Mackbeth", to our great content, and then home, where the women went to the making of my tubes, and I to the office, and then come Mrs. Turner (age 45) and her husband to advise about their son, the Chaplain, who is turned out of his ship, a sorrow to them, which I am troubled for, and do give them the best advice I can, and so they gone we to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 21 Dec 1668. Thence to the Duke's playhouse, and saw "Macbeth". the King (age 38) and Court there; and we sat just under them and my Baroness Castlemayne (age 28), and close to the woman that comes into the pit, a kind of a loose gossip, that pretends to be like her, and is so, something. And my wife, by my troth, appeared, I think, as pretty as any of them; I never thought so much before; and so did Talbot and W. Hewer (age 26), as they said, I heard, to one another. The King (age 38) and Duke of York (age 35) minded me, and smiled upon me, at the handsome woman near me but it vexed me to see Moll Davis (age 20), in the box over the King's and my Baroness Castlemayne's (age 28) head, look down upon the King (age 38), and he up to her; and so did my Baroness Castlemayne (age 28) once, to see who it was; but when she saw her, she looked like fire; which troubled me. The play done, took leave of Talbot, who goes into the country this Christmas, and so we home, and there I to work at the office late, and so home to supper and to bed.

Pepy's Diary. 15 Jan 1669. Thence he and I out of doors, but he to Sir J. Duncomb (age 46), and I to White Hall through the Park, where I met the King (age 38) and the Duke of York (age 35), and so walked with them, and so to White Hall, where the Duke of York (age 35) met the office and did a little business; and I did give him thanks for his favour to me yesterday, at the Committee of Tangier, in my absence, Mr. Povy (age 55) having given me advice of it, of the discourse there of doing something as to the putting the payment of the garrison into some undertaker's hand, Alderman Backewell (age 51), which the Duke of York (age 35) would not suffer to go on, without my presence at the debate. And he answered me just thus: that he ought to have a care of him that do the King's business in the manner that I do, and words of more force than that. Then down with Lord Brouncker (age 49) to Sir R. Murray (age 61), into the King's little elaboratory, under his closet, a pretty place; and there saw a great many chymical glasses and things, but understood none of them. So I home and to dinner, and then out again and stop with my wife at my cozen Turner's where I staid and sat a while, and carried The. (age 17) and my wife to the Duke of York's (age 35) house, to "Macbeth", and myself to White Hall, to the Lords of the Treasury, about Tangier business; and there was by at much merry discourse between them and my Lord Anglesey (age 54), who made sport of our new Treasurers, and called them his deputys, and much of that kind. And having done my own business, I away back, and carried my cozen Turner and sister Dyke to a friend's house, where they were to sup, in Lincoln's Inn Fields; and I to the Duke of York's (age 35) house and saw the last two acts, and so carried The. (age 17) thither, and so home with my wife, who read to me late, and so to supper and to bed. This day The. Turner (age 17) shewed me at the play my Baroness Portman (age 29), who has grown out of my knowledge.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Measure for Measure

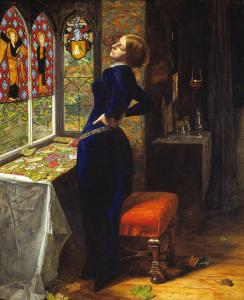

1850 to 1851. John Everett Millais 1st Baronet (age 20). "Mariana". The character in the Shakepeare play Measure for Measure and Tennyson's peom Mariana in the Moated Grange.

1850 to 1851. John Everett Millais 1st Baronet (age 20). "Mariana". The character in the Shakepeare play Measure for Measure and Tennyson's peom Mariana in the Moated Grange.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Merry Wives of Windsor

Pepy's Diary. 15 Aug 1667. Thence with much satisfaction, and Sir W. Pen (age 46) and I to the Duke's house, where a new play. The King (age 37) and Court there: the house full, and an act begun. And so went to the King's, and there saw "Merry Wives of Windsor" which did not please me at all, in no part of it, and so after the play done we to the Duke's house, where my wife was by appointment in Sir W. Pen's (age 46) coach, and she home, and we home, and I to my office, where busy till letters done, and then home to supper and to bed.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Midsummer's Night's Dream

Pepy's Diary. 29 Sep 1662. So we parted, and in the park Mr. Cooke by appointment met me, to whom I did give my thoughts concerning Tom's match and their journey tomorrow, and did carry him by water to Tom's, and there taking up my wife, maid, dog, and him, did carry them home, where my wife is much pleased with my house, and so am I fully. I sent for some dinner and there dined, Mrs. Margaret Pen being by, to whom I had spoke to go along with us to a play this afternoon, and then to the King's Theatre [Map], where we saw "Midsummer's Night's Dream", which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life. I saw, I confess, some good dancing and some handsome women, which was all my pleasure.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Othello

Pepy's Diary. 20 Aug 1666. Waked this morning, about six o'clock, with a violent knocking at Sir J. Minnes's (age 67) doore, to call up Mrs. Hammon, crying out that Sir J. Minnes (age 67) is a-dying. He come home ill of an ague on Friday night. I saw him on Saturday, after his fit of the ague, and then was pretty lusty. Which troubles me mightily, for he is a very good, harmless, honest gentleman, though not fit for the business. But I much fear a worse may come, that may be more uneasy to me. Up, and to Deptford, Kent [Map] by water, reading "Othello, Moore of Venice", which I ever heretofore esteemed a mighty good play, but having so lately read "The Adventures of Five Hours", it seems a mean thing.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Feb 1669. Up, and to the office, where all the morning, and thence after dinner to the King's playhouse, and there,-in an upper box, where come in Colonel Poynton and Doll Stacey, who is very fine, and, by her wedding-ring, I suppose he hath married her at last,-did see "The Moor of Venice" but ill acted in most parts; Mohun, which did a little surprise me, not acting Iago's part by much so well as Clun used to do; nor another Hart's, which was Cassio's; nor, indeed, Burt doing the Moor's so well as I once thought he did.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Romeo and Juliet

1870. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 26). Study for "The Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet".

1870. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 26). Study for "The Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet".

1871. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 27). "The Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet".

1871. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 27). "The Tomb Scene from Romeo and Juliet".

Pepy's Diary. 01 Mar 1662. Thence my wife and I by coach, first to see my little picture that is a drawing, and thence to the Opera, and there saw "Romeo and Juliet", the first time it was ever acted; but it is a play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life, and the worst acted that ever I saw these people do, and I am resolved to go no more to see the first time of acting, for they were all of them out more or less.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, The Taming of the Shrew

Pepy's Diary. 09 Apr 1667. So home to dinner, and after dinner I took coach and to the King's house, and by and by comes after me my wife with W. Hewer (age 25) and his mother and Barker, and there we saw "The Tameing of a Shrew", which hath some very good pieces in it, but generally is but a mean play; and the best part, "Sawny"1, done by Lacy (age 52), hath not half its life, by reason of the words, I suppose, not being understood, at least by me.

Note 1. This play was entitled "Sawney the Scot, or the Taming of a Shrew", and consisted of an alteration of Shakespeare's play by John Lacy (age 52). Although it had long been popular it was not printed until 1698. In the old "Taming of a Shrew" (1594), reprinted by Thomas Amyot for the Shakespeare Society in 1844, the hero's servant is named Sander, and this seems to have given the hint to Lacy (age 52), when altering Shakespeare's "Taming of the Shrew", to foist a 'Scotsman into the action. Sawney was one of Lacy's (age 52) favourite characters, and occupies a prominent position in Michael Wright's (age 49) picture at Hampton Court [Map]. Evelyn, on October 3rd, 1662, "visited Mr. Wright, a Scotsman, who had liv'd long at Rome, and was esteem'd a good painter", and he singles out as his best picture, "Lacy (age 52), the famous Roscius, or comedian, whom he has painted in three dresses, as a gallant, a Presbyterian minister, and a Scotch Highlander in his plaid". Langbaine and Aubrey both make the mistake of ascribing the third figure to Teague in "The Committee"; and in spite of Evelyn's clear statement, his editor in a note follows them in their blunder. Planche has reproduced the picture in his "History of Costume" (Vol. ii., p. 243).

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, The Tempest

1870. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 26). "The Tempest".

1870. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 26). "The Tempest".

1872. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 28). "Study for The Tempest, Ferdinand and Miranda playing chess".

1872. Emma Lucy Madox Brown (age 28). "Study for The Tempest, Ferdinand and Miranda playing chess".

Pepy's Diary. 07 Nov 1667. Up, and at the office hard all the morning, and at noon resolved with Sir W. Pen (age 46) to go see "The Tempest", an old play of Shakespeare's, acted, I hear, the first day; and so my wife, and girl, and W. Hewer (age 25) by themselves, and Sir W. Pen (age 46) and I afterwards by ourselves; and forced to sit in the side balcone over against the musique-room at the Duke's house, close by my Lady Dorset (age 45) and a great many great ones. The house mighty full; the King (age 37) and Court there and the most innocent play that ever I saw; and a curious piece of musique in an echo of half sentences, the echo repeating the former half, while the man goes on to the latter; which is mighty pretty. The play [has] no great wit, but yet good, above ordinary plays.

Pepy's Diary. 13 Nov 1667. Thence home to dinner, and as soon as dinner done I and my wife and Willet to the Duke of York's (age 34), house, and there saw the Tempest again, which is very pleasant, and full of so good variety that I cannot be more pleased almost in a comedy, only the seamen's part a little too tedious.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Jan 1668. Thence, after the play, stayed till Harris (age 34) was undressed, there being acted "The Tempest", and so he withall, all by coach, home, where we find my house with good fires and candles ready, and our Office the like, and the two Mercers, and Betty Turner (age 15), Pendleton, and W. Batelier. And so with much pleasure we into the house, and there fell to dancing, having extraordinary Musick, two viollins, and a base viollin, and theorbo, four hands, the Duke of Buckingham's (age 39) musique, the best in towne, sent me by Greeting, and there we set in to dancing.

1875. John William Waterhouse (age 25). "Miranda". Miranda gazing out to sea watching the ship fail in the storm at the commencement of The Tempest.

1875. John William Waterhouse (age 25). "Miranda". Miranda gazing out to sea watching the ship fail in the storm at the commencement of The Tempest.

Miranda: he was born to Duke Prospero.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Titus Andronicus

In Jan 1596 John Harington 1st Baron Harington (age 56) produced a performance of Titus Andronicus and a masque written by his brother-in-law Edward Wingfield of Kimbolton (age 34) at Burley-on-the-Hill House. The event was mentioned in a letter from Jacques Petit to his master Anthony Bacon (age 47).

Edward Wingfield of Kimbolton: Around 1562 he was born to Thomas Wingfield of Kimbolton Castle and Honora Denny. Before 1603 Edward Wingfield of Kimbolton and Mary Harrington were married. In 1603 Edward Wingfield of Kimbolton died.

Anthony Bacon: In 1549 he was born to Nicholas Bacon Lord Keeper and Anne Cooke. In 1601 Anthony Bacon died.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Twelfth Night

Around 1788 John Hoppner (age 29). Portrait of Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan" (age 26) playing the character Viola in Twelfth Night.

Around 1788 John Hoppner (age 29). Portrait of Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan" (age 26) playing the character Viola in Twelfth Night.

Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan": On 21 Nov 1761 she was born near Waterford, County Waterford. On 05 Dec 1761 she was baptised at St Martin in the Fields. On 05 Jul 1816 she died.

Pepy's Diary. 11 Sep 1661. After he was ready we went up and down to inquire about my affairs and then parted, and to the Wardrobe, and there took Mr. Moore to Tom Trice, who promised to let Mr. Moore have copies of the bond and my aunt's deed of gift, and so I took him home to my house to dinner, where I found my wife's brother, Balty (age 21), as fine as hands could make him, and his servant, a Frenchman, to wait on him, and come to have my wife to visit a young lady which he is a servant to, and have hope to trepan and get for his wife. I did give way for my wife to go with him, and so after dinner they went, and Mr. Moore and I out again, he about his business and I to Dr. Williams: to talk with him again, and he and I walking through Lincoln's Fields observed at the Opera a new play, "Twelfth Night"1 was acted there, and the King there; so I, against my own mind and resolution, could not forbear to go in, which did make the play seem a burthen to me, and I took no pleasure at all in it; and so after it was done went home with my mind troubled for my going thither, after my swearing to my wife that I would never go to a play without her. So that what with this and things going so cross to me as to matters of my uncle's estate, makes me very much troubled in my mind, and so to bed. My wife was with her brother to see his mistress today, and says she is young, rich, and handsome, but not likely for him to get.

Note 1. Pepys seldom liked any play of Shakespeare's, and he sadly blundered when he supposed "Twelfth Night" was a new play.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Jan 1663. So to my brother's, where Creed and I and my wife dined with Tom, and after dinner to the Duke's house, and there saw "Twelfth Night"1 acted well, though it be but a silly play, and not related at all to the name or day.

Note 1. Pepys saw "Twelfth Night" for the first time on September 11th, 1661, when he supposed it was a new play, and "took no pleasure at all in it"..

Viola

Around 1788 John Hoppner (age 29). Portrait of Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan" (age 26) playing the character Viola in Twelfth Night.

Around 1788 John Hoppner (age 29). Portrait of Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan" (age 26) playing the character Viola in Twelfth Night.

Dorothea Bland aka "Mrs Jordan": On 21 Nov 1761 she was born near Waterford, County Waterford. On 05 Dec 1761 she was baptised at St Martin in the Fields. On 05 Jul 1816 she died.

Books, Shakespeare's Plays, Winter's Tale

In 1779 Mary "Perdita" Darby aka Robinson (age 21) gained popularity when she played the role of Perdita in Florizel and Perdita, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Winter's Tale. It was during this performance that she attracted the notice of the young Prince of Wales, the future King George IV of Great Britain and Ireland (age 16). At this time Amy "Emma Hart Lady Hamilton" Lyon (age 13) sometimes worked as her maid and dresser at the theatre.

Perdita

In 1779 Mary "Perdita" Darby aka Robinson (age 21) gained popularity when she played the role of Perdita in Florizel and Perdita, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Winter's Tale. It was during this performance that she attracted the notice of the young Prince of Wales, the future King George IV of Great Britain and Ireland (age 16). At this time Amy "Emma Hart Lady Hamilton" Lyon (age 13) sometimes worked as her maid and dresser at the theatre.