Archaeologia Volume 12 Section XXV

Archaeologia Volume 12 Section XXV is in Archaeologia Volume 12.

Discoveries in a Barrow [Fin Cop Barrow [Map]] in Derbyshire. In a Letter from Hayman Rooke (age 72), Esq. to Mr, Gough, Read February 11, 1796.

Mansfield Woodhouse, February 1, 1796.

Dear Sir,

I have ventured to send you a little account of some relics lately found in a barrow in the Peak of Derbyshire.

About the latter end of last winter, Mr. Robert Needham, jun. of Ashford, a very respectable farmer, who rents an estate of the duke of Devonshire, was induced to destroy a large barrow for the sake of procuring a great quantity of lime-stones, of which it was chiefly formed.

Having been informed that this barrow contained fome curious remains of antiquity, I sent to desire Mr. Needham would preserve the relics, and not proceed to a farther search in the barrow (which I was told had not been entirely cleared), till I came to examine it; and he very obligingly assured me, that he had already taken care of the antiquities, which he would reserve for my acceptance, and that the barrow should not be touched. It is but justice to the politeness of Mr. Needham to mention this instance of his readiness to assist the Antiquary in his researches.

I went twice last summer to examine the barrow, which is situated on the summit of a hill that has a gradual rise from the South-east, and at about two miles North-west from Ashford. This hill is called Fin Cop. These are evidently British names, with but little variation from their radicals Fyn and Coppa; the former in the ancient Cornish and British language signifies an end, or a boundary, which this hill has on every side, and Coppa the top or summit.

At about seventy-two yards South-east of the barrow is a work [Fin Cop, Derbyshire [Map]] thrown up, with a ditch on the inside of the vallum, which surrounds the top of the hill except on the North-west fide, where there is a precipice fourteen yards from the barrow; at the distance of one hundred and fixty yards beyond this work is another ditch and vallum, where the ditch is on the outside.

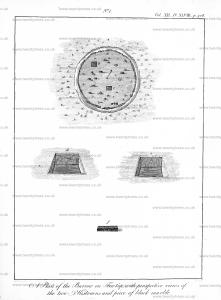

Fig. (a) in Pl. XLVIII is a plan of the barrow after I had cleared away more of the sides; circumference one hundred and sixty-one feet. It had been raised to a considerable height, and formed with lime-stones of various sizes, mixed with a very fine dry mould. In the bottom at (b) and (c) are two kistvaens; (b) is cut into the solid rock, which incloses three ssides, on the other is a flat stone, and one of the same kind was placed on the top; the kistvaen (c), which, is rather smaller than the other, was formed in the natural soil, with flat stones fixed in the sides, and one in the bottom. See a perspective view of these at (d and e).

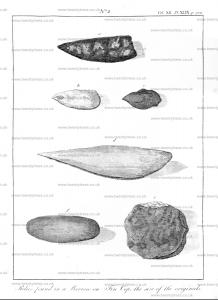

In the kistvaen (b), was a skeleton placed with its face, downwards, and on the top of the scull was an oblong piece of dressed black Derbyshire marble, which plainly appeared to have been fixed to the scull by a strong cement, part of which now adheres to the stone and scull. Under the head were found two arrow-heads of flint, the slze of the [Note. Missing text here?] fig. (a) and (b) in Pl. XLIX. This kistvaen was only two feet nine inches by two feet and one foot nine inches deep. The black stone (f) in Pl. XLVIII. which was placed on the head, is two feet in length, nine inches broad, and six inches thick.

At the South-east end of the barrow three urns, of very coarse baked earth, were found nearly together, full of ashes and burnt bones, but so much decayed that they fell to pieces in taking up. I measured a fragment of the top rim of one, which did not appear to have been more than six inches diameter, but, from another fragment of a rim, the urn must have been much larger; on the top of one was a flint head of an arrow, the slze of (c) in PL XLIX.

At the East end of the barrow two more skeletons were deposited on the level ground. With these was picked up the spear head (d), PL XLIX. which is shaped out of a piece of lime-stone, and made very sharp at the point.

The flat circular stone (e), Pl. XLIX. was taken out of the kistvaen (b), Pl. XLVIII. It has a thin body of stucco on both sides; the top is of a yellowish colour, and plainly appears to have been varnished. This possibly might have been some ornament to the dress of those rude times in which this body was inhumed.

The smooth stone (f), PL XLIX. was found on the top of one of the urns. It differs only in shape from the common boulder stones, which, though usually met with in sandy grounds, are not to be found in the Peak on a lime-stone soil. It is therefore probable, that the superstitious Britons might have preferved these kind of stones as scarce and valuable amulets; and I am more inclined to be of that opinion from having, some years ago, met with two stones similar to this deposited with some others on Stanton-moor.

The preservation of the teeth, in the jaws of these skeletons, which stiil retain their ivory, is very remarkable; the bones also are but little decayed. This might probably be owing to the very light dry earth with which they were covered.

The kistvaen (e), Pl. XLVIII. was full of ashies and burnt bones, and possibly was the spot where the bodies might have been burnt.

The bones were thrown promiscuously in, and the principal care seems to have been in placing and fixing the piece of marble to the scull, nor, indeed, was there room for the body to be deposited at full length. It is probable, therefore, that the body might be burnt, and the bones collected and placed in the kistvaen; for, I should imagine, whilst there is the least moifture left in the body the bones would not be damaged; but where we find the bones reduced to a very fine powder in urns, we may conclude that they were burnt over again by themselves after the body was consumed: but I shall leave this to the learned Society, who will, most probably, form a more plausible conjecture.

I am much inclined to think that this elevated spot, thus secured by a double fence, may be the site of a British town or fortress, and that the barrow was the sepulchre of the chieftain and his relatives. There evidently appears to have been more attention paid to the bones inhumed in the kistvaen (b), than to any of the rest, from this singular instance of a piece of black marble being fixed on the scull. As this kistvaen is too small to admit of the body at full length, may we not suppofe that the body was first burnt, and the allies deposited in the kistvaen (c), which seems to have been designed for that purpose, and the head and bones placed by themselves, as above mentioned?

It seldom happens, that interment and urn burial are to be met with in the same barrow. The former is undoubtedly the most ancient, and has been handed down to us by sacred history and authentic records. We find also, that the practice of burning the body was of great antiquity, and here the same ancient weapons were found deposited with both; I therefore think there is great reason to suppose, that this barrow was of very remote antiquity.

The reverend Mr. James Douglas, in his learned and elegant Sepulchral History of Great Britain, speaking of these arrow-heads of flint, says, "They are evidences of a people not in the use of malleable metal; and it therefore implies, that, wherever these arms are found in barrows, they are incontestibly the relics of a primitive barbarous people, and preceding the aera of those barrows in which brass or iron arms are found1".

If you think this little memoir will be acceptable to the Society, I muft beg you will do me the honor to prefent it to them.

I am,

Dear Sir,

your sincere and obliged humble Servant,

H. ROOKE.

Note 1. Naenia Britannica, p. 154, note 3