Archaeologia Volume 20 Section V

Archaeologia Volume 20 Section V is in Archaeologia Volume 20.

Account of the Tomb of Sir John Chandos, Knt. A.D. 1370, at Civauux a hamlet on the Vienne, in France; by Samuel Rush Meyrick (age 40), LL. D. F.S.A. In a Letter addressed to Henry Ellis, Esq. F. R. S. Secretary. Read 5th April 1821.

College of Advocates, Doctors Commons, April 2, 1821.

My Dear Sir,

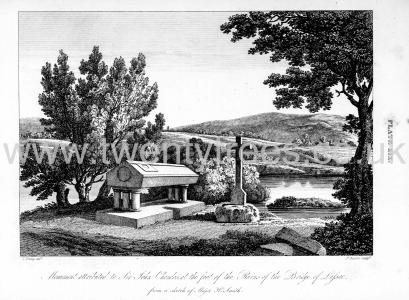

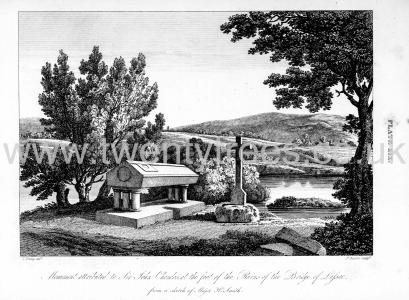

THERE exists in France a Monument which tradition ascribes to the" Flower of English Chivalry," Sir John Chandos, who fell in a skirmish near the bridge of Lusac in the year 1370. A friend of mine, Major Smith, has lately visited this spot, and from his letter, and some other sources, I have drawn up the following, which through your means I beg leave to submit to the notice of the Society of Antiquaries. The subject seems to me interesting on two accounts; first, from the great celebrity and renown of the hero intended to be commemorated, and next for the peculiarity of the monument itself.

M. Siauve, a Member of the Societ6 d'Emulation at Poictiers, was deputed to survey, and make a report upon the tombs at Civaux, a hamlet on the Vienne, about six leagues from Poictiers, on the high road to Limoges, and the result of his researches was published in the year 1804. Not far from this village he found the monument which tradition affirms, and he readily believes, to be that of Sir John Chandos. He says, that" the tomb in its present dilapidated state consists of a flat stone, over which a cenotaph is raised on two small pillars, having sculptured on it a pennon with a device, a small heart-shaped buckler, and the shaft of a halbert, or battle-axe. At one end is a round vacant space, which is supposed to have contained his armorial bearings, described by Froissart as a pile Gules on a field Argent. The bones of this knight are supposed to be still undisturbed beneath his ruined monument."

That the ignorance of the peasantry, who have nothing to guide them but the tradition, should incline them to believe this to be the monument of Sir John Chandos is natural, but that a gentleman, who is a professed Antiquary, should, in opposition to Froissart and Bouchet, assent to the notion that the bones of the hero are under the cenotaph he describes, is truly astonishing. This circumstance, however, besides the very interesting and picturesque manner in which that able Chronicler has described the death of Sir John Chandos, has induced me briefly to state what he has said on the subject. It will be found at length in his eleventh chapter.

He relates that the occurrence which occasioned his death arose from his continual regret at the loss of St. Salvin, and his repeated meditation on the most effectual means for its recovery. On the eve of the new year he attempted to carry into effect the project of taking it by escalade, but failed, imagining that the stratagem had been discovered. He then dismissed the Poitevins, and remained at an hotel at Chauvigne on the river Creuse, with his more immediate retainers. After this, hearing that the French had taken the field, he determined on seeking and bringing them to battle. They were posted on one side of the bridge of Lusac, while the English, who had first quitted Sir John, drew up on the other, determined to intercept the passage. Sir John and his party keeping the same side of the river as the French, came suddenly on their rear, but without being at all aware that any of their friends were on the other. A skirmish began, in which Sir John, from not having closed the vizor of his helmet, received the thrust of a lance in his eye, which entered his brain, and caused his death. His body was valiantly defended by his uncle Sir Edward Clifford, until the arrival of the English from the other side occasioned the French to yield themselves prisoners of war. Sir John Chandos was then gently disarmed, placed on shields and targets, and carried to the castle of Mortemer, the nearest fortress. There he survived but one day, and there he was buried.

This account in the original carries with it internal evidence of impartiality, and the author seems to have derived his information from an eye-witness.

Bouchet goes still further to prove, that Sir John Chandos was buried at Mortemer. He has preserved, in his" Annales d' Aquitaine," the epitaph which he says was placed on his monument there. It ran thus:

Je Jehan Chandault, des Anglois capitaine.

Fort Chevalier, de Poictou Seneschal,

Apres avoir fait guerre tres lointaine Au Rois Francois, tant a pied qu'a cheval,

Et pris Bertrand de Gueselin en un val,

Les Poitevins prés Lusac, me different,

A Mortemer mon corps enterrer firent,

En une cercueil elevd tout de neuf,

L'an mil trois cens avec seixante neuf.

" I John Chandos, Captain of the English,

A powerful Knight, Seneschal of Poitou,

After having for a very long time made war

On the French kings, as well on foot as on horseback,

And taken Bertrand de Gueselin in a valley,

Was destroyed by the Poitevins near Lusac.

At Mortemer they caused my body to be enterred

In a coffin,a put up quite new, in

The year one thousand three hundred and sixty-nine."

Note a. It was usual at this time to make the monument contain the coffin.

In Froissart's account, the skirmish took place on the last day of December, and then Sir John received his mortal wound, but he seems to have died on the evening of the first of January. This difference will enable us to reconcile the date in the epitaph with that of the Chronicler. Or, perhaps as the year, more strictly speaking, commenced in March, the monument may not have been finished before that time.

But it is now time for me to refer to the letter of my friend Major Smith. He writes as follows:" We set out for the shrine of Sir John Chandos, of valiant memory. Our road was towards the castle of Mortemer, where Froissart asserts he died and was buried, though the French writers say that his tomb is by the road side near Civaux. In order to obtain the best intelligence, we sought the Curé of the village, but our efforts were in vain. Thus disappointed, we entered the yard of the Castle, where we found a stone-cutter following his occupation. Having addressed our queries to him, he informed us, that he and his companions were then at work repairing the floor of the church, and that there were but two monumental stones in it. Of these, but one had any inscription, merely commemorating a chanoine, and that he had turned face downwards. Having entered and examined the church without discovering any clue towards identifying the grave, and the declaration of the stone-mason having aroused the spirit of antiquarian disquisition in me, I fancied the man had ignorantly read Chanoine for Chandos. I therefore prevailed on his master to take up the stone. To my mortification I found it dated 169.., a convincing proof of my error. The other monumental stone without inscription, was ridged, or in the coffin-shape, and probably belonged to the ancient barons of Mortemer, a branch of the English Mortimers. They had a vault in the church, and the body of our great countryman may have been deposited within it, bqt of this neither vestiges nor tradition remain. The geographical position of the Castle and its strength fully admit Mortemer to have been the nearest strong-hold to the Vienne which the English then possessed.

"Quitting this place we went towards Masserolles, and from that into the great road from Poictiers to Lusac and Limoges. This brought us immediately upon the Vienne, which appeared to be near sixty yards in breadth. While waiting here, and making enquiry for the monument of Sir John Chandos, and the ruins of the ancient bridge of Lusac, a merchant informed us we were within a few hundred yards of the spot. On this joyful intelligence my companion and I pushed forwards to catch a view of our principal object. Having ascended the bank to a small hamlet, the first thing that struck us was a green mass in the stream. This proved to be a remaining vestige of a former arch, and at the pier nearest to us we found the monument in question. A countryman standing by, observed that it was the tomb d'un chevalier Anglois nomme Chandos,' that it had been thrown down during the Revolution, and lately replaced on its ancient base by himself and companions. It consists of a ridged coffin-shaped lime-stone block, supported by two uprights, each formed to resemble a range of three pillars, and these resting on a broad and thick slab of the same material. On one side of the bevil of the surface is a bas-relief of a banner, with a square depression in it forming a border, a within which some idle fellow has attempted to scratch a few cross lines, to designate the union flag of England. On the other, or left side, is a lance tapering to a point, but without the usual flat-bladed head, and by it a kite-shaped shield, like those in the Bayeux tapestry. At the head end of this block is a round defaced surface, which we were told contained his armorial bearings, chisseled out at the Revolution.

About three feet from the right side of this tomb is a stone cross, no doubt denoting, as is common in Catholic countries, the violent death of a person on this spot, which is in fact the foot of the bridge, and therefore referring to the monument. No inscription, however, appears on either." See Plate XIX.

But there is another point still to be accounted for. The Major has justly remarked, that it is usual to erect a cross where a violent death has occurred, and that the stone one at the foot of the bridge evidently refers to the monument. I would further add, that its position is such as to obstruct the passage, so that it could not have stood there previous to this skirmish.

I think, however, the difficulty is to be solved in the following manner. The English" deposited in a coffin quite new," their heroic chief within the vault at Mortemer, and erected within the church a tablet, bearing the epitaph preserved by Bouchet. When the place fell into the hands of the French, this, with its inscription, was wholly destroyed, as it would not be found palatable to national vanity. In a very different light, however, would be considered the manner in which Sir John Chandos was killed. This was worthy of commemoration, as it seemed to cast a ray of glory on the arms of France. For such a purpose, an ancient monument was requisite, and the church-yard of Civaux abounded with them. Correctness in chronology was not understood: it was sufficient that the monument be prior to the age, and this was removed from its original site to record the fall of a warrior who died, probably, two hundred and fifty years after him for whom it was originally designed.

If the round defaced surface at the head of the tomb had the armorial bearing of Sir John Chandos, it was most likely carved in bas-relief at the time of its removal, to countenance the national sentiment; for which likewise, when changed, it was subsequently obliterated.

Accompanying this Letter are two Drawings, one representing the position of this Monument, and the other the Castle of Mortemer. At the end also, the Monument is so sketched as to shew the appearance of both its upper faces.

Of the family of the hero who is the subject of this letter, my worthy friend Francis Martin, Esq. Windsor Herald, Fellow of this Society, has furnished me with the following pedigree from documents in the College of Arms.c

Note c. Vincent's Chaos. 21.

From this Pedigree it appears that the origin of the Chandos family is to be referred to that of John de Monmouth. Of this chieftain Enderbie, in his" Cambria Triumphans," p. 300, gives the following account.

" In the year 1234 John Lord Monumetensis, a noble warrior, captain or general of the king's army, being made Ward of the Marches of Wales, levied a power, and came against Earl Marshall and the Welshmen, but when he had once entered Wales he came back in post, leaving his men for the most part slain and taken behind." This history is reported by Matthew Paris after this manner." About the feast of St. John Baptist, John of Monmouth, a noble and expert warrior, who was with the King in his wars in Wales, gathered a great army, meaning to invade the Earl Marshal at unawares, but he being certified thereof, hid himself in a certain wood, by the which lay the way of his enemies, intending to deceive them who went about to do the like by him. When the enemies therefore came to the place where the ambuscado was, the Earl Marshal's army gave a great shout, and so set upon their enemies, being unprovided, and suddenly put them all to flight, putting to the sword an infinite number of them, as well Poictavians as others. John of Monmouth himself escaped by flight, whose country, with the villages, buildings, and all that he had therein, the Earl Marshal did spoil and plunder, leaving nothing but what fire and sword could not destroy, and so full fraught with spoil returned home."

The event thus related from Matthew Paris, p, 526, alludes to the period at which William Marshall Earl of Pembroke had formed an alliance with Llewelyn Prince of Wales to oppose Henry III.

I find the name of John of Monmouth in the List of Sheriffs for Herefordshire, as serving that office in the 15th Henry III. Although the pedigree does not notice Henry de Monmouth, he was probably the brother or son of this John, and is mentioned in the Plac. Coron. 20 Edw. I. as holding lands in the parish of Marden in Herefordshire, by service," pro qua debet summonire dominos deWiggemore apud Wiggemore, Braos apud Gingston, et de Cary apud Webbeley, et distringere eos pro debitis domini Regis cum necesse fuerit, et conducere thesaurum domini Regis &castro Hereford usque London, et habere quolibet die xii d. Et quia servicium debile est, ideo mutatus de consensu ejusdem Henrici, ita quod dictus Henricus reddat domini Regi per an.xiic?. Etfaciet servicium 40m® partis feodi unius militis, et sic quietus sit de praedicto servicio." "By which it is his duty to summon the Lords of Wiggemore at Wiggemore, Braos at Ginston, and De Cary at Webbeley, and to distrain them for debts due to our Lord the King when it shall be necessary, and to conduct the treasure of our Lord the King from the Castle of Hereford to London, and to have every day twelve pence. And forasmuch as the service is now due, it is therefore commuted by consent of the said Henry in such manner that the said Henry shall render to our Lord the King twelve pence a year: and he shall do the service of the fortieth part of one knight's fee, and so be released from the aforesaid service." Isabel, whom Robert Chandos married, may however have been his heir, as this would account for her conveying to her husband estates in Herefordshire.

In the parish of Great Marclay in that county is the mansion house of Chandos, which is supposed to have received its name from that family.

The Rev. Mr. Buncombe, in his" History of Herefordshire," quotes an old MS. which contains a List of the Knights of the County who served in the wars of Edward I. Among them is the name of Sir Roger de Chaundos, whose arms are therein stated to be," Or, a lion rampant Gules, et la queue fourchie." This Roger de Chandos was Sheriff of Herefordshire, in the 5th, 6th, 7th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th of Edward II. and in the 1st, 2nd, 3d, 4th, 5th, 8th, and 9th of Edward III. Thomas Chandos his son served the same office in the 34th, 46th, 47th, and 48th of the same King.

Of Sir John Chandos, the immediate subject of this paper, I have been able to collect the following Notes.

Ashmole mentions, in his" Order of the Garter," that he and Roger de Chandos were knighted in the 24th of Edward III. He next appears as one of those heroes who distinguished themselves in the battle of Cressy, and who united with the Earl of Warwick, the Earl of Oxford, and Sir Reginald Cobham, in the propriety of despatching a messenger to the King to let him know of his son's danger, that he might send him assistance. The King's dignified refusal on this occasion is well known, and the young Prince won his spurs.

Sir John seems about this time to have formed the resolution of devoting his life wholly to the military service of his country; for in" Blount's Tenures" we find that in the 28th Edward III. anno 1354, Robert Brug sold to Peter Grandison the lands which John Chandos held in Marcle, (probably Great Marclay,) Herefordshire.

Three years after the battle of Cressy the Order of the Garter was instituted, to be conferred principally on those who had distinguished themselves on that occasion. Sir John Chandos was accordingly one of the twenty-five original knights.

In the next campaign we find him appointed one of the Marshals, and ordered, with Lord James Audeley, another, to accompany the Black Prince in his march through Touraine to Bourdeaux. While thus commanding an advanced guard, he fell in with a knight named Griffith Mico,d in the service of France, sent with two hundred horse to reconnoitre. Of these he took thirty prisoners, with their commander, the rest being all slain.

Note d. In all probability Myg, or" the glorious," some Welshman.

When Remorantin was besieged, the town being taken, the French forces retired to the castle; Sir John Chandos was on this occasion appointed by the Prince of Wales to confer with them on the surrender of the fortress, but, his terms being refused, the place was taken and destroyed on the 4th of September 1356.

Fifteen days after was fought the celebrated battle of Poictiers. During this action Sir John had never stirred from the Prince's side till, seeing the van of the French wholly discomfited, he advised the Prince to ride directly to the attack of the King's battail or line.

Notwithstanding these heroic details, it is with far more pleasure that we have next to record a humane action. Almost immediately after this advice which Sir John had given, the Chastellain of Amporta, a chief captain of the Cardinal Perigort de Talleyrand, was taken prisoner. The Black Prince ordered his head to be struck off, but Sir John interposed and saved him, thus blending magnanimity with courage.

In this memorable battle the King of France was taken prisoner, and when he was afterwards ransomed, to Sir John Chandos was confided the honourable office of seeing that the terms of agreement on the part of the English were properly fulfilled. Leland, in his Cf Collectanea,"e mentions the circumstance in the following words:" And upon these treatice John Chandos, Knight, was sent with sufficient authority, that delyveraunce might be made of such fortresses and holdes as the Englishmen had there won."

Note e. Vol. I. p. 578.

In the next expedition of the King of England, when he invaded France with the largest army that had ever crossed the sea, he was also accompanied by Sir John Chandos. This gallant Knight being sent with a detachment against the strong castle of Cernov en Dormois, succeeded in gaining possession of it. He was next employed in negociating a truce with the Regent, which, however, the high demands of the King of England rendered unsuccessful.

In the year 1362 King Edward appointed his son Prince of Aquitain, on which that hero did not forget his companion in arms, but, at once, nominated Sir John Chandos Constable of all that territory.

When the Black Prince undertook his Spanish enterprize in favour of Peter the Cruel, we find Sir John associated with John of Gaunt Duke of Lancaster in carrying on the negociations with the King of Navarre: after which, on the Prince commencing his march, those great men led the first column, or battail, f as it was then called.

Note f. Hence our word Battalion.

The renowned Bertrand Du Guesclin, a fit competitor with the Prince of Wales for military glory, fought on the side of Don Henry. He was, however, captured by Sir John Chandos, and is reported to have expressed himself satisfied at" being in the hands of the most generous Prince living, and made prisoner by the most renowned Knight in the world."g

Note g. Froissart.

Bertrand was ransomed, and from that period the success of the English began to decline. Still, however, Sir John Chandos acted with his usual energy, and being sent with a body of troops to Montauban, was successful in his attacks. He not only kept the frontiers, but made many inroads into the enemy's territory, in one of which he took possession of Terriers in Tholouse. He had, however, to regret that he could not send assistance to the English garrison in Realville, who were consequently all put to the sword.

It was some alleviation, that he shortly after was able to take the strong town of Moissac, and though he might have retaliated this cruel proceeding, he contented himself with compelling the inhabitants to swear fealty to the Prince of Wales.

We next find this great captain honoured by having a herald called after him by the title of Chandos. This officer he employed, but in vain, to summon several towns to surrender; the consequence was, that Roquemados and Ville Franche de Perigort were besieged, and yielded to the arms of Sir John and the Knights under his command. On being recalled, he assisted the Black Prince in the capture of La Roche sur Yon, a strong castle belonging to the Due d' Anjou, which was immediately garrisoned by English.

The signal services of Sir John Chandos, now induced the Prince of Wales to confer on him the Seneschalship of Poitou. On this appointment he went to reside at Poictiers. The town of St. Salvin in that Province, on the river Gartempe, had in it an English garrison, all the inhabitants, including the monks, having sworn allegiance to the Black Prince. One of these monks, it is said from hatred to his superior the abbot, betrayed the town into the hands of the French. This event gave the greatest vexation to Sir John Chandos, and, as was stated in the commencement of this Letter, ultimately led to his death.

From all that is related by Froissart, Sir John Chandos appears to have been a truly great man; by his courage he obtained rewards from his own country and respect from his enemy; and he shewed his piety, according to the superstition of the day, by the foundation of a Carmelite Monastery at Poictiers. By his benevolent and humane conduct he set an example of moderation worthy to be followed, and obtained the gratitude of those he governed; and by his superior good sense and discernment, was often employed in negociations, referred to in doubtful cases, and quoted as an authority by his cotemporaries and immediate posterity.

I have therefore thought this tribute due to his memory, which I hope will not be unworthy the notice of the Society:

Remaining, my dear Sir,

very faithfully yours,

Sam. R. Meyrick.