Archaeologia Volume 30 Section IV

Archaeologia Volume 30 Section IV is in Archaeologia Volume 30.

09 Feb 1843. Account of the opening by Matthew Bell, Esq. of an ancient British Barrow, in Iffins Wood [Map], near Canterbury, in the month of January, 1842, in a Letter from John Yonge Akerman (age 36) Esq. F.S.A., to Sir Henry Ellis, K.H., F.R.S., Secretary.

Read 9th February 1843.

Dear Sir Henry, Lewisham, Feb. 6, 1843.

The various groups of tumuli in the eastern parts of Kent are well known to our English antiquaries; and it is a fact pretty generally established, that they are referable to a period extending from the time of the abandonment of this Island by the Romans (and perhaps earlier) down to the establishment of Christianity, when it became the practice to inter the dead in some consecrated place, within the precincts of the church. To this period belong the numerous barrows on Barham Downs, near Canterbury ; and the excavations recently made by Lord Albert Conyngham in the group on Breach Downs, adjacent to the village of Barham, prove that they also are of the same age.

The result of these excavations is of considerable importance to the antiquary. A stranger visiting the spot would, without the information thus afforded, at once conclude that these barrows were raised over the remains of the slain at an earlier period of our history.

If we turn to the Commentaries of Czsar, and read bis account of the second landing of the Romans, we may safely conclude that between the coast and these downs numbers must have fallen on both sides, and that their interment on or near the spot followed as a matter of course.

In the month of December last, I was present at the excavation by Lord A. Conyngham of several other tumuli in Bourne Park, which were evidently of the same class as those in the immediate neighbourhood of Barham Downs, doubtless once of much greater extent.

From this we may infer that if tumuli were raised over the remains of the Romans and Britons who fell in Czsar’s second expedition, it was in some other locality than in those where barrows of the Roman-British and AngloSaxon period are now known to exist. That at least one of the places of British interment has been found, I am convinced, from the subjoined particulars of the opening of a tumulus by T. W. Bell, Esq., on his estate at Oswalds, near Canterbury, obligingly communicated to me by that gentleman, together with the sketches from which the accompanying drawings have been made.

About two miles south-east of Canterbury is a place called Jfins Wood, a little to the right of the Roman road called Stone Street, which ran from Durovernum to the Portus Lemanis, (Lymne,) near Hythe.

The eastern extremity of the wood extends to this Roman way, which at that spot is used by the farmers for their waggons, &c. A little further on, it becomes the public road to Hythe. The wood comprises about 150 or 180 acres, and "was formerly," says Hasted, "the site of the manor of Ytching, as it was spelt in Henry VIths time, and within it are the vestigia of an ancient camp, the outward trenches of which contain about eight acres. There are numbers of different intrenchments throughout this large wood, and one vallum especially which runs on to the Stone Street road. At the north corner of this camp are the remains of an oblong square building of flint, the length of it standing east and west. At the east end was to be seen (many years ago) a square rise against the wall seemingly for an altar, and the pedestal of a gothic pillar was found amongst the rubbish; so that if this ever was a pretorium of a Roman general, a chapel seems to have been erected on the site of it, as was frequently the case, probably by the owners of the manor, and to have been deserted when this part of the country was depopulated by the contests between the houses of York and Lancaster. The remains of fortifications in this wood are by many supposed to be on the place to which the Britons retreated after they were driven by the Romans from their hold in the woods, which Cesar says, ‘ was fortified both by art and nature,’ and where he again found them with their allies under the command of Cassivilaunus, and fought his decisive battle with them.”

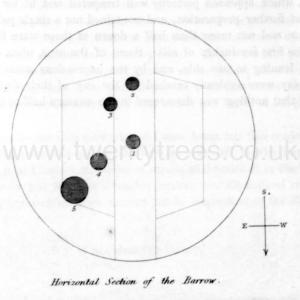

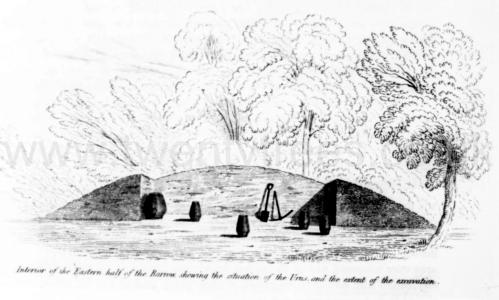

The foundations of the chapel here mentioned are still to be seen; and about 250 yards to the westward is a tumulus 150 feet in circumference, and nearly six feet high. ‘I commenced operations,” observes Mr. Bell, “ by causing a trench, four feet broad, to be cut through the centre of the barrow, north and south. In this trench we discovered the urns 1 and 2, (see Vignette), and also a portion of No. 3. In order to extricate the latter, a square excavation was made in the barrow from top to bottom, on the left hand side of the trench, and in doing this the two urns, 4 and 5, were discovered. I then ordered a similar square excavation to be made on the right side of the trench, and this was carried through nearly to the outside of the barrow, but nothing else was found. Four of the five urns thus brought to light were precisely alike in size and form ; but the fifth was much larger, and slightly different in shape and ornament, the former being eighteen inches in height, and thirteen inches in diameter at the broadest part, and the latter not less than twenty-five inches in height, and twenty-two in diameter. The material of which these urns were composed was of the rudest description, consisting of half-baked clay, mixed with numerous fragments of silex, which crumbled at the touch, so that their removal entire was impossible.

“The urns were all found with their mouths downwards, filled with ashes, charcoal, and minute fragments of bones. The contents of the larger urn were perfectly dry, and the portions of bone were larger, but those of the smaller ones were very moist, and of the consistence of paste. The mouths of the urns were closely stopped with unburnt clay, which appeared to have been firmly rammed in.

“Not a vestige of any weapon, bead, or other ornament could be discovered. The soil of which the barrow was formed was most excellent brick earth, which appeared perfectly well tempered and fit for immediate use, without further preparation, and contained not a single pebble larger than a bean, and not more than half a dozen of these were found after removing the first few inches of soil. Some of the urns, when uncovered, were found leaning to one side, and by the impressions made in the surrounding clay were evidently cracked on the day of their deposit. It is remarkable that nothing was discovered in the western half of the barrow.

The urns (the only ornament on which was a row of indentations, apparently made with the end of the finger) were standing on nearly the same level as the surrounding ground, which, on digging into it, appeared not to have been disturbed ”

Such is the account which Mr. Bell gives of these interesting remains. On the opinion of Antiquaries, cited by Hasted, he remarks that it is probable the trenches, &c. in Iffins Wood, are in reality the remains of the encampment where Cesar defeated the Britons under their king Cassivelaunus, and that the barrow was raised over the remains of the Britons who fell in that battle, especially when we consider the rudeness of the materials and workmanship of the urns, and that, (as mentioned above,) some of them were, when discovered, cracked and standing awry. They were not placed in the centre of the barrow, or arranged in any regular order; all which seems to indicate that they may have been deposited with that haste and want of ceremony, which would necessarily accompany the burial of the slain after a defeat.

A reference to the Commentaries of Cesar bears out this conjecture ; yet if the remains are not those of the Britons who fell in the important engagement under Cassivelaunus, but of others who perished in the same campaign, in brave but fruitless struggles against the disciplined ranks of the invader, an account of them cannot but be interesting to the English Antiquary.

I am, dear Sir Henry, Very faithfully yours,

J. Y. AKERMAN. Sir Henry Evus, K.H., F.R.S. Sec. S.A.