Archaeologia Volume 32 Section XXIII

Archaeologia Volume 32 Section XXIII is in Archaeologia Volume 32.

Observations on the celebrated Monument at Ashbury, in the county of Berks, called "Wayland Smith's Cave [Map]" by John Yonge Akerman (age 40), Esq. F.S.A. in a Letter to Capt. W. H. Smyth, R.N. Director. Read, 4th March, 1847.

Lewisham, 3d March, 1847.

My Dear Sir

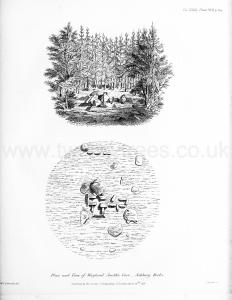

I beg to submit through you to the Society of Antiquaries, drawings, from actual admeasurement, by Mr. C. W. Edmonds, of that interesting monument of the Celtic period, popularly known as "Wayland Smith's Cave," (Pl. XVII.) situated at Ashbury, in the county of Berks.

At a period when Antiquarian researches are prosecuted with so much zeal and vigour, anything that may assist our knowledge of the manners and customs of the early races in Britain cannot but prove interesting. We are, it is to be hoped, no longer in danger of seeing the most curious remains of antiquity gradually perishing under the united assaults of ignorance and cupidity.

" Wayland Smith's Cave" is a cromlech of the Celtic period. It stands about a mile and a half west of the famous White Horse, cut in the chalk of the downs at Uffington, of which a representation was communicated by me to the 31st volume of the Archseologia, and within a hundred yards of an ancient road called the u Ridgway," which passes eastward over Whitehorse Hill towards Ilsley, and westward over the hills above the villages of Ashbury, Bishopstone, &c., towards Avebury. The stones once composing the "cave," and lying in disorder about the spot, are called Sarsens," or "grey weathers." They are of the same quality as those at Abury and Stonehenge.

The vault or cave was formed, as usual in these sepulchres, by upright stones covered by large slabs at the top. Of the latter, but one remains; a large quantity of stone having been taken from this place some time since for the purpose of building a barn! The accompanying drawing and ground-plans show the present state of this interesting monument, which it is greatly to be regretted has suffered so much under rude and ignorant hands.

It will be observed in this cromlech that there are two lateral chambers, or transepts, giving to the entire ground-plan the form of a cross. These chambers would alone be sufficient to negative the absurd idea of these stones having been raised as altars for human sacrifices; a supposition indulged in by the speculative antiquaries of this and other countries up to the present time, but which has, at length, received a more decided refutation by the researches of Mr. Lukis among the cromlechs existing in the Island of Guernsey, detailed by him in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association.

It appears evident, from the scattered fragments lying around, that, although these chambered tumuli have been almost obliterated, they were often originally inclosed within a circle of stones. Traces of this circle are still visible around the cromlech at Ashbury; and in the arrangement of the vault, though differing in some respects, we recognise a striking similarity to that of the dilapidated Cromlech du Tus, as shown in a drawing which accompanies this communication, copied from Mr. Lukis's representation of the ground-plan of that monument.

It seems probable that the whole of the areas formed by these outer circles, which may be considered as marking the limits or base of the tumulus of earth which once covered the sepulchral chamber, were sacred to interments; that these circles formed, in fact, what the Anglo-Saxons in after times called the lictun; that here the remains of the humble and obscure rested, while those of persons of exalted rank were consigned to the principal vault. The exploration of the mound of a perfect chambered tumulus may establish or disprove this. Successive interments in the same solitary tumuli of the Celtic period are very common, but there are not very many examples of the practice in the clustered tumuli of the Anglo-Saxon era.

A word in conclusion on the popular tradition of "Wayland Smith," which a beautiful fiction has immortalised. In my note on the White Horse already alluded to, I have ventured to express a doubt of that object having been the work of the Anglo-Saxons, at least of the Christianised Anglo-Saxons, and have referred it to an earlier period. I leave the discussion of this curious subject to abler heads, and shall merely observe that popular tradition is at all times a better theme for the poet and the novelist than for the sober and inquiring, the fact-loving and painstaking antiquary. The country-people tell you that, in former times, if a traveller's horse cast a shoe as he passed that way, he had only to lead his steed to the cave, place a groat on the cap-stone, and retire for a while; on returning he would find the horse shod, and the money gone! They have another story, of the invisible smith; that he was plagued with a disobedient apprentice, who being one day chastised by his master ran away, and when at the distance of a mile, Wayland Smith cast a huge stone at the fugitive, which struck him on the heel, leaving the print of the boy's foot on the stone! The boy sat down and cried at this spot, which to this day is called by the rustics Snivellin Carrier! This solitary stone, much mutilated, is still to be seen in the corner of a meadow at a place called Old-stone Farm.

I am,

My dear Sir,

Very faithfully Yours,

John Yonge Akerman.

Captain William Henry Smyth, R.N., F.R.S. Director S.A., &c. &c. &c.