Archaeological Journal

Archaeological Journal is in Prehistory.

The Archaeological Journal is the annual peer-reviewed publication of the Royal Archaeological Institute. Published since 1844.

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 1

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 3

Archaeological Journal Volume 3 Page 148

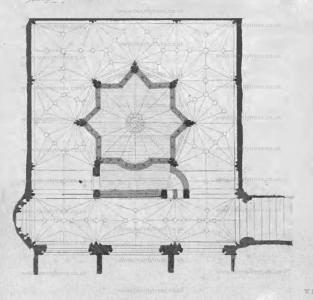

St Winefrid's Well, Holywell [Map] at Holywell, Flintshire by Ambrose Poynter.

St. Winefrede was a noble British virgin, who suffered martyrdom in the seventh century. Her head was smitten off by a Welsh Tarquin, named Caradoc, who instantly met with his reward in being swallowed up by the earth. The lady's head bounded down the hill on which the catastrophe occurred, and, stopping near the church, a copious spring of water burst from the place where it rested. Her blood sprinkled the stones ineffaceably, and a fragrant odour was imparted to the moss growing on the spot. All these, however, are but the more trifling circumstances of the miracle. A holy man, one St. Benno, took up the head and fitted it so cleverly on the body, that the parts re-united, and St. Winefrede survived this remarkable adventure fifteen years.

This veracious history—for the hill, the fountain, the blood and the moss, remain as triumphant evidences of its truth— has been commemorated by a most elegant Gothic structure in the Perpendicular style, the date of which may be placed on heraldic evidence ante 1495.

The building inclosing the well is erected against the side of the hill from which the water issues, and forms a crypt under a small chapel contiguous to the parish church, and on a level with it, the entrance to the well being by a descent of about twenty steps from the street. The well itself is a star-shaped basin, ten feet in diameter, canopied by a most graceful stellar vault, and originally inclosed by stone traceried screens, filling up the spaces between the supports. Round the basin is an ambulatory, similarly vaulted. These arrangements, and the form and decoration of the building, are better explained by the engravings.

The water rises from a bed of shingle with great impetuosity. From the main basin it flows over into a smaller one in front, to which access is obtained by steps on both sides, for the purpose of dipping out the water, and from thence into a large reservoir outside the building. From the latter the water passes by a sluice into the service of a paper mill, and, after putting in motion the machinery of several manufactories, falls into the Dee at a distance of about nine furlongs from its source.

The neglected state of this beautiful edifice having forced itself upon the notice of the inhabitants of Holywell, a subscription was entered into, and the proceeds, about £400, have been expended in disengaging the chapel from some unsightly erections built against it, in restoring the windows, and in some general repairs necessary to maintain it for the purpose of a school-room, to which it is now put; but nothing has been expended on the crypt, which is, nevertheless, independently of the mutilation of the screens and decorations, in a state to excite the apprehension of all lovers of antiquity. Nor are the gentlemen to whom the expenditure of the fund has been entrusted open to blame on this account. The difficulties of effecting any substantial repair, when it is most likely to be wanted, are great and peculiar, so much so, that it is not easy even to speak with certainty on the actual condition of the substructure.

The water, as already stated, rises with great force from a bed of shingle, on which the inclosure of the basin and the supports of the vaulting have been founded without any excavation; and in order to prevent the effects of the shingle washing away, the overflow of the basin is raised about four feet (the depth is unequal) from the bottom, and the sluices of the mill raise the surface of the water about two feet higher. This depth of water, in violent agitation, even when the sluices are opened, and the water above the overflow let off, effectually prevents the possibility of seeing the bottom of the basin, but by sending workmen into the water, it was ascertained that the shingle has disappeared from under the foundations of the walls of the basin, in some places nearly as far as the men could thrust in their arms, and in one instance at least, a squared stone has given way. This disappearance of the foundation, notwithstanding the judicious precaution originally taken to secure it, might appear a mystery, but that the well, in the days of ignorance, was frequented by bathers, who, it is believed, pulled out the pebbles, and carried them away as memorials of the miraculous properties of the water. In the original state of the building, the main basin was protected by the screens, but these have been broken down long enough to allow for the gradual abstraction of the bottom in this manner and to this extent.

Whatever may be the cause, such is the effect, and under such circumstances this beautiful building cannot but be considered in a state of peril, which calls at least for further examination, although as yet the arches do not exhibit any marks of settlement. It is possible that the contingency of the shingle becoming loosened, or washing from under the wall, may have been provided for. There is evidently a great mass of masonry in the substructions, and it is quite consistent with what is known of the constructive skill of the architects of the thirteenth century, when they thought it worth while to exert it, to suppose that stones of such large size may have been laid down, that they may continue to support the superstructure in the manner of corbels, but it is not easy either to ascertain the fact, or to apply the operation of under-pinning, should it prove to be requisite. To obtain access to the foundations, it would be necessary to empty the basin, and discharge the water as it rises; and in order to effect this, the front of the basin must be taken down, and a channel as deep as the bottom of the basin cut through the outer reservoir, depriving the mill of its moving power as long as the repairs might be in hand. With so formidable an undertaking to contend with, it is cause less of surprise than of regret that the late repairs should have been restricted to the more accessible portions of the building, and that there should be no measures in prospect for its permanent security.

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 6

Archaeological Journal Volume 6 Proceedings 01 Jun 1849

BY Mr. C. Faulkner.—A curious gold ring, discovered at Barton, Oxfordshire; it is octagonal, each side being irregularly lozenge-shaped. (See woodcut.) The facets appear to have been formed by placing the gold wire, formed into a hoop, on a tool similar to what is termed a beak iron, and hammering the upper part till each side had obtained the desired shape. This is shown by the indentations made by the rough instrument, the sharp edges between each lozenge on the inner side, and the hammer marks seen on the flat surface of each side externally. Weight, 3 dwts. 16 grains. Diameter, seven-eighths of an inch. It has been supposed to be a relic of the early British age9: it was found under the foundations of a wall, not far from a cromlech [Hoar Stone, Steeple Barton [Map]], which was broken in pieces and removed from the field where it stood some years since. This destruction of a venerable memorial having become known to the landlord, he compelled his tenant to bring back the fragments, which now form a heap, surrounded by a fence. No account of this cromlech appears to have been recorded.

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 11

Archaeological Journal Volume 11 Proceedings

Mr. Birch communicated further notices which he had received from Mr. Jenkins, of Hereford, relating to ancient remains in the neighbourhood of St. Margaret's Park and the cruciform earth-work already noticed in this Journal. (See vol. x. p. 358.) With permission of the proprietor excavations had been made in that singular embankment, at three different places, but without making any discovery: it has also been cleared of the brush-wood which encumbered it, and may now be fully examined. Not far distant may be noticed several basins or cavities of considerable size, supposed to have been possibly the sites of ancient habitations, and in one of these hollows some ancient pottery had been found, which, it is hoped, may be obtained for examination, as this might supply a clue to the probable date of these works. It was stated that a cross of metal had been found in the Park and sent to London. About 250 yards N.E. of the cruciform embankment in St. Margaret's Park there is a flat horizontal slab of limestone [Park Wood Long Barrow [Map]], like the upper stone of a cromlech. It is of an irregularly oval form, measuring about 27 feet 6 inches by 9 feet 6 inches; average thickness, 2 feet 6 inches in the direction of the longer diameter, being north and south. This stone lies on the declivity of the wooded hill, its face on the western side being level with the adjacent surface of the ground, and on this side there is a trench, 2 feet wide, and 2½ feet deep, which appears to have been at one time much deeper, and to have been filled up by soil brought down by the rain into it. On the east side, and partly on the north, the ground slopes from it, and a cavity appears under the slab. Half a century ago, as stated by an old man in the neighbourhood, it stood wholly free from the ground, resting on certain upright stones. There is still at the west end of the slab, but now at a slight distance from it, an upright stone, flat at top, which may have originally been one of those on which it was supported. It seems probable that these may be the remains of a fallen cromlech. About half a mile south of the cross-shaped mound and cavities above mentioned several objects of bronze have been found in ploughing, of a type hitherto, as it is believed, un noticed. They may have been fixed on the ends of spear-shafts, to serve the purpose of a ferrule. ( See woodcut, half length of original, ) The length of this object is 5 inches, the socket within tapers to a point 11 inch from the extremity.

Near St. Margaret's Church, about 500 yards west, and three quarters of a mile from the cross earthwork, the head-stone here represented (see woodcut) is to be seen in the fence of a tillage-field, under an aged yew tree, which leans, through the force of prevalent winds, in the same direc tion as the grave-slab at its foot. The dimensions are 4 feet by 17 inches. Tradition affirms that a lady was there buried, who came from London infected with the plague and died here. Another tale is, that seven persons were there interred at some remote period.

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 15

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 18

Archaeological Journal Volume 18 Will of Henry Dene

The Will Of Henry Dene, Archbishop Of Canterbury, Deceased 15 February, 1502—3. Communicated By The Rev. John Bathurst Deane, M.A., F.S.A.

KING HENRY VII., as it has been observed by Lord Chancellor Bacon, "was not afraid of an able man, as Lewis the eleventh was; but contrariwise, he was served by the ablest men that were to be found, without which his affairs could not have prospered as they did. For war, Bedford, Oxford, Surrey, D'Aubigny, Brooke, Poynings; for other affairs, Morton, Fox, Bray, the Prior of Lanthony, Warham, Urswick, Hussey, Frowick, and others."

The Prior of Lanthony, thus commended by so distinguished an historian, was Henry Dene1, who successively became Chancellor and Justiciary of Ireland, Bishop of Bangor, from which see he was speedily translated to that of Salisbury, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and Archbishop of Canterbury. The merit which caused his elevation to such high dignities, must have been, as recognised by Lord Bacon, of no ordinary character; we do not find that, either by birth or connections, he enjoyed the advantages of family interest. He was probably a native of Gloucestershire, born about 1430, and, according to tradition, as stated in the Athenss Oxonienses, near Gloucester2, an obscure member, it may be supposed, of the ancient family of Dene, of Dene in the Forest of Dean, settled near St. Briavels' Castle as early as the reign of Henry I., or of that branch which, in the reign of Edward III., was seated at Yatton in Herefordshire.

Note 1. Sometimes written Deane, or Denny. In the sepulchral inscription given by Weever, the name is Dene, as likewise in Pari. Writs and other records. In Pat. Edw. IV. regarding the union of the two Lanthonys, it is written Deen.

Note 2. This tradition appears to be supported by numerous details connected with the history of Henry Dene, and which were brought before the Institute in the Memoirs communicated by the Rev. J. Bathurst Deane to the Historical Section at the Meeting in Gloucester, July, 1860. The collateral evidence tending to show that the Archbishop may confidently be numbered amongst Gloucestershire Worthies was then fully stated. W e hope that Mr. Bathurst Deane may hereafter fulfil his purpose of publishing, in more ample form, these contributions to the history of the ancient family of Dene, including the Biography of the Archbishop, and a Memoir of Sir Anthony Deane, Chief Commissioner of the Royal Navy in the reign of Charles II., whose Treatise on Naval Architecture, in the Pepysian Library, would form a desirable addition to such a volume of Parentalia.

He was educated at Oxford, as stated by M. Parker, Godwin and other writers;3 it has been asserted that he was of New College4, and took his doctor's degree there; his name lias not been found, however, in the Registers of Winchester College. In 1 Edward IV., 1461, he became Prior of Lanthony near Gloucester, at that period designated Lanthonia Secunda, being a cell to the Priory of Canons of St. Austin at Lanthony in Monmouthshire; subsequently it became the principal house, the two Lanthonies having been united, 21 Edward IV., 1481. The reasons assigned by the king for that measure were the exposure of Lanthonia Magna, from its being in the Marches, to the incursions of the Welsh, by which it had become so wasted and ruined, that divine worship and the regular observance of the order had ceased; the accustomed hospitality and alms were altogether neglected: also, that John Adams, Prior of the said Lanthony in Monmouthshire, had wasted the revenues, and daily did more waste and destroy the same, having moreover in the said Priory not more than four canons—"minus religiose viventes." These facts having come to the king's knowledge, and also that by the prudent government of the Prior and Convent of Lanthony near Gloucester, divine worship and regular observances were there duly performed with great honor and decency, as far as their revenues sufficed, the right of patronage, advowson of the priory or conventual church, with all the possessions of Lanthony prima, in Wales, were granted by Edward IV. to Henry Dene, Prior, and to the Convent of Lanthony secunda, and to their successors, in consideration of three hundred marks paid into the king's hands.5 It is probable that considerable works were carried out under the direction of Prior Dene at Lanthony near Gloucester; the gateway still existing, and on which an escutcheon of his arms, a chevron between three birds, may be seen, was doubtless built by him.6 These birds, sometimes blazoned as Cornish choughs, may be regarded as the Danish ravens, in allusion to the name of Dene.7 Such an allusion, it may be rememberedj has been pointed out in a former volume of this Journal, in a valuable memoir on an heraldic window in York Cathedral, associated with the name of Peter de Dene, a canon of that church in the fourteenth century, as the donor.8

Note 3. The Epistle to the University, cited by Anthony a Wood, Athense Dxon. ed. Bliss, vol. ii. p. 690, as from Archbishop Dene, and containing an allusion to Oxford as his "benignissima mater," will be found appended infra.

Note 4. This supposition appears to rest only on the statement of Godwin, De Press. p. 132; "in Collegio Novo Oxonias educatum testatur in Ecclesiastica historia Barpfeldius, utcunque Cautabrigienses eum pro suo vendicent." No such circumstance is stated by Harpsfeld, who says that Warham (not Dene) was of New College. Archbishop Dene is admitted into Cooper's Athena? Cantabrigienses, pp. 6, 620, but the researches of the compilers of that valuable work do not appear to have found any evidence in support of his supposed connection with Cambridge.

Note 5. Pat. 21 Edw. IV., 10 May, 1481. Monast. Angl. new edit. vol. vi. p. 139.

Note 6. This gateway forms the subject of a beautiful etching by Coney, in the Monasticon, ut supra.

Note 7. The arms attributed to Henry Dene, when Archbishop, and given by Willement in his Heraldic Notices of Canterbury Cathedral, p. 157, as formerly existing in the Hall of the archiepisco pallace, are—Arg. on a chevron gu. inter 3 birds sa. as many crosiers of the field. In MS. Lambeth, 555, cited by Mr. Riland, in the "Blazon of Episcopacy," p. 4, the crosiers are blazoned or, instead of argent. They may have been added in allusion to the Archbishop's triple preferment, Bangor, Salisbury, and Canterbury. The Archbishop's arms occurred "on painted bricks," probably paving tiles, at the Black Friars, Gloucester, to which he may have been a benefactor. Rudge, Hist. Glouc. p. 315. Such tiles were also in the Lady Chapel at Gloucester Cathedral.

Note 8. Archaeol. Journal, vol. rvii. p. 28.

The abilities of the Prior of Lanthony, as Bishop Godwin remarks, were recognised by Henry VII., as we have seen that they had been by his predecessor Edward IV. The interest, through which his advance ment may have been promoted, has not been recorded. It has been stated that he was indebted to Cardinal Morton for preferment; in September, 1495, he was appointed Chancellor of, Ireland, where the cause of Perkin Warbeck had from the first been espoused by numerous adherents to the House of York, and where under the nominal government of the young Prince Henry, Duke of York, with Sir Edward Poyniugs as Deputy, a conciliatory policy, fraught with difficulties, had been adopted. The return of the Pretender, who had been cordially received by Margaret, Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, was a serious cause of apprehension. Through the talents and energy of the Deputy and the Chancellor, who is designated by the chronicler Hall—"a man of great wyt and diligence," the disaffected nobles were brought to obedience, the Irish Parliament was prevailed upon to pass the memorable statute known as the Poynings Act, which established the authority of the English government in Ireland, and tranquillity was fully restored, so that when Warbeck appeared at Cork in the following year, the Irish refused to venture their lives in his cause. Henry was doubtless well pleased with the mission; the first mark of his favor occurred on the death of Richard Ednam, Bishop of Bangor, probably towards the close of 1495, when Prior Dene was preferred to that see;9 on January 29 following, the king, fully confiding in the fidelity and prudent sagacity of Henry, Bishop of Bangor, constituted him, on the recall of Sir Edward Poynings, Deputy and Justiciary of Ireland.10

Note 9. Pat. 12 Hen. VII. The temporalities of the see of Bangor do not appear to have been restored to him until Oct. 6, 1496; 12 Hen. VII, See Le Neve's Fasti, ed. Hardy, vol. i. p. 103.

Note 10. 11 Hen. VII., "apud Westm. die Jan 29." Lansd. MSS. vol. xliv. p. 31.

The see of Bangor was at that period in a very neglected coudition, and its cathedral ruinous; Godwin relates the evils which had arisen from perpetual dissensions between the Welsh and the English, non-residence of previous bishops, and the cupidity of the neighbouring nobles who had possessed themselves of its property. Bishop Dene addressed himself with energy to remedy these evils. Amongst the ancient possessions of Bangor there was an Island, situated off the northern extremity of Anglesea, and called the "Isle of Seals," in Welsh,—Ynys y Moel Rhouiaid, now known as the Skerries. It is thus described by Matthew Parker, in his Life of Archbishop Dene:—"Es t ad septentrionem insulas Monss, quam Angleseiam jam nuncupant, inter promontoria Corneti ejusque quod Caput Sanctum dicitur, interposita insula quam veteri Britannico vocabulo Ynys, sive Moyl, Rhoniad, i.e. pliocarum seu alitum insulam, voeant, quia ea marina animalia magno ibidem numero verno et autumuali tempore singulis annis capiantur." De Antiqu. Brit. Eccl. ed. Drake, p. 451. It appears by the Record of Caernarvon, which gives—·" partem W. Gruffith in insula Eocarum," that many persons had acquired rights in the island, and by a list of "Carte facte super Insulam Focarum per diversos," ibid. p. 253, we learn that great part of the shares, or "gwelys," had been bought up from various owners by William Griffith in the reign of Henry VI. It further appears by a document amongst the archives of Bangor Cathedral, printed by Browne Willis in the Survey of that church, Appendix, p. 244, that the ancient right of fishing in that isle, appertaining to the Bishop and the church of Bangor, having been some time disused, Bishop Dene in person went thither, by assent of all his tenants of the lordship of Cornewylan, Sir William Griffith, of Penrhyn, excepted, and that the bishop's servants took, on 7 October, 149S, "twenty-eight fishes called Grapas." Sir William Griffith sent his son with men in arms, and seized the fish by force. Bishop Dene, however, compelled him to make restitution, and established his right as lord of the fisheries of the island.12 According to another account of this characteristic transaction, a number of Irish had effected a settlement there, and refused to recognise the superiority of the Bishop of Bangor, or to pay any rent. Bishop Dene took vigorous measures; having obtained a decision or formal declaration as to the legality of the claim, he proceeded in person with an armed force to the island, and speedily reduced the intruders to submission.13 The cathedral and episcopal palace he found in a ruinous condition, never having been restored since their destruction by Owen Glendower, in the reign of Henry IV.: he rebuilt the choir, and was actively engaged in works of restoration, when, in 1499, he was translated to Salisbury14, On the death of Cardinal Morton, Lord Chancellor, 15 September, 1500, Henry VII. made choice of the Bishop of Salisbury as his successor; and on 13 October following he delivered the Great Seal to him at Woodstock, but with the title of Lord Keeper only.15 It is remarkable that hitherto he had been permitted to retain his earliest preferment, that of Prior of Lanthony, in commendam.16

Note 12. Willis's Bangor, pp. 95,244; Pennant's Wales, vol. ii. p. 274. See also Godwin, p. 132; Hist, of Anglesea, p. 39.

Note 13. Weever, Fun. Mon. p. 231, describes this island as situated between Holyhead and Anglesea, and called "Moilr homicit," the Island of Seals; it is, however, the island about 7 miles N. of Holyhead, called Ynys y Mod Rhoniaid, or commonly, the Skerries; the fishery, as it is said, still belongs to the church of Bangor. According to Browne Willis, one of Bishop Dene's successors, Bishop Robinson, in the reign of Elizabeth, alienated the island to hie son. In the declaration regarding Seals-Island, B. Willis, p. 244, it is called "Seynt Danyel's Isle," doubtless from Daniel, first bishop of Bangor.

Note 14. He succeeded John Blythe, who died 23 Aug., 1499; the custody of the temporalities was granted 7 Dec., and plenary restoration made 22 March following.

Note 15. Claus. 16 Hen. VII.

Note 16. "Henricus episeopus Sarum Prioratum Ecelesie B. Marie juxta Gloeestriam in commendam tenuit." Reg. Sar. cited by Bishop Kennet, Coll. MS. Brit. Mus.

This mark of royal favor was only the preliminary to the highest distinction which could be conferred upon him. The see of Canterbury having shortly after become vacant, by the death of Thomas Langton, elected as successor of Cardinal Morton, but before his translation had been perfected, Henry Dene, Bishop of Salisbury, was elected 26 April, 1501; the temporalities were restored 7 August following;17 and the pall was sent by the eloquent Hadrian Castellanus, the Pope's Secretary, and Legate to Scotland, but it was delivered by the Bishop of Coventry. The ceremonial on this occasion is given by Bishop Godwin. It is remarkable that, as has been recorded, he never was installed. In the same year he was constituted by Pope Alexander VI. Legate of the Apostolic See. Bymer, torn. xii. p. 791.

Note 17. Rymer, Foed. tom. xii. p. 773. "Pat. 16 Hen. VII. Teste Rege apud Lanthony," 7 -Aug. The king may have been on a visit to Henry Dene, possibly still Prior at that time.

In the following year the Archbishop, feeling doubtless the increasing infirmities of age, resigned the Great Seal on 27 July, 1502, devoting himself wholly to the duties of his high station in the Church. No parliament had been held during the period that he had been Lord Keeper. He rebuilt great part of the archiepiscopal manor-house at Otford. It is also recorded that he repaired Rochester Bridge, and strengthened the coping or parapet with iron-work. His name appears only twice on great public occasions, but those were interesting and important, namely, the nuptials of Prince Arthur with Catherine of Aragon, solemnised in St. Paul's, 14 November, 1501, and the negotiations for the marriage of the Princess Margaret with James IV. King of Scots. At the first Archbishop Dene officiated with nineteen mitred bishops; a lively narrative of the sumptuous ceremonial is given by the chronicler Hall. The negotiations for the marriage of the princess occupied a considerable time, and required great diplomatic delicacy. Three commissioners of tried abilities were selected, namely, the Archbishop, Fox, Bishop of Winchester, and the Earl of Surrey; the matter was at length brought to a successful issue. The term of Henry Dene's long and busy life now drew towards a close, and in anticipation of death he made his will, remarkable for the omission of all allusion to his own origin and connexions, and for the singularly minute attention with which he gave directions regarding his obsequies, the place and manner of his interment, the services for the repose of his soul, the alms to be dispensed on the occasion. The most urgent entreaties were addressed to his executors, Sir Reginald Bray, the Archdeacon of Canterbury, and two others, that they would faithfully carry out his last wishes. He died at Lambeth, 15 February18, 1502—3; the instructions regarding the transport of his remains to Canterbury and their interment in the Martyrdom with solemn obsequies, to which he had appropriated in his lifetime no less a sum than 500l., were carried out under the superintendence of his chaplains, Thomas Wolsey and Richard Gardiner, appointed to that duty by his executors. The corpse was transported by the Thames to Faversham in a barge, attended by thirty-three mariners in black attire, with candles burning; and thence conveyed by the same attendants to Canterbury in a funeral car (feretro).19 Upon the coffin was placed an effigy (ad similitudinem), sumptuously vested in pontificals; sixty gentlemen accompanied the procession on horseback; fifty torches blazed around the corpse; it was interred on the feast of St. Mathias the Apostle (February 24), near the resting-place of Archbishop Stafford in the Martyrdom at Canterbury Cathedral, in accordance with the directions in his will. A fair marble stone inlaid with brass was there placed as his memorial. This existed when Weever compiled his "Funerall Monuments"21 he has recorded the inscription which may also be seen in Somner's Canterbury, Appendix, p. 4. The monumental brass was preserved as late as 1644, when it was seen by Joseph Edmonson, as stated in Hasted's MS. Collections in the British Museum; it probably was destroyed in the Civil Wars, when according to tradition so large a number of fine memorials were despoiled in Canterbury Cathedral, and the metal was sold to the brass-founder.22

Note 18. In the Obituary of the Monks of Canterbury the date is given as 16 Feb. Ang. Sac. t. i. p. 124. The inscription on the tomb (Weever) and MS. records of the church of Canterbury give 15 Feb. See also the authorities cited by Godwin, de Præs. p. 133.

Note 19. Antiqu. Rot. cited by Bishop Kennet, MS. Brit. Mus. The particulars regarding the convoy to Canterbury Cathedral are extracted from a MS. Register of that church.

Note 21. Ancient Funerall Monuments, p. 232; published in 1631.

Note 22. Archbishop Dene's tomb in the Martyrdom is thus noticed by Leland: "In the cross isle betwixt the body of the chirche and the quire northward ly buried Pechem and Wareham. Also, under flate stones of marble, Deane, afore priour of Lanthony, and another bishop." Itin. vol. vi. p. 5. The slabs, stripped of the brasses, are mentioned by Hasted as existing when his history of Kent, published in 1778, was compiled.

The pious and benevolent purposes so minutely set forth in the followingdocument appear to have been in great part frustrated. In an Obituary amongst the archives of the church of Canterbury, a remarkable monition may be found how vain are the most careful testamentary provisions. It is there recorded of Archbishop Dene,—"Iste Archiepiscopus non habuit memoriam xxx. dierum, ut mos est Archiepiscoporum, propter paupertatem. Erat valde deceptus per executores suos; multa bona reliquit post se, sed executores sui sceleratissimi furabantur, ut dictum est."3 The onerous avocations of the Archbishop's friend and principal executor, Sir Reginald Bray, and probably his declining health, prevented doubtless his giving the supervision and personal direction so earnestly solicited in the will. Sir Reginald died in the following year. His character stood too high to admit of a suspicion that he participated with the "executores sceleratissimi" in the spoils. Thomas Wolsey, destined so speedily to occupy a prominent position in public affairs, had been taken from his rectory of Limington near Ilchester, where he had incurred some disgrace, and became chaplain to the Archbishop, in whose will his name does not occur, although, as it chanced, the charge of carrying out the last wishes of his patron was confided to him.

Note 3. Anglia Sac. vol. i. p. 124.

The Will Of Archbishop Dene. Extracted From The Principal Registry Of Her Majesty's Court Of Probate In The Prerogative Court Of Canterbury. (Register Blamyr, Fo. 181 Vo.).4

Note 4. A transcript of the Will of Archbishop Dene is preserved at Canterbury, Somner, Antiqu. of Cant, part ii. p. 78. states that it is found there in Reg. D. The following copy is preserved in the Register of Thomas Goldstone, Prior of Canterbury, amongst wills proved, sede vacante, before Roger Church, doctor of decrees, deputed as keeper of the Prerogative.

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 20

Books, Prehistory, Archaeological Journal Volume 28