CWAAS Transactions 1886 Volume 8 Article 32 More Divock

CWAAS Transactions 1886 Volume 8 Article 32 More Divock is in CWAAS Transactions 1886 Volume 8.

Article XXXII - The Prehistoric Remains On Moordivock [Map], Near Ullswater. — By M. Waistell Taylor, M.D., (Ed.) F.S.A., (Scot.) Communicated at Carlisle, July 23, 1885.

In the descriptions of the great peristylithic monuments of Cumberland and Westmorland, given by the old authorities, Camden, Stukely, Gough, Lysons and others, there are inaccuracies and a certain looseness of delineation, and their errors have been iterated in our county histories, and in other works in which the descriptions have been taken at second-hand. But the Transactions of this Society now afford trustworthy records for future reference. The great stone circles of Long Meg [Map], Keswick [Map], Gunnerkeld [Map], Eskdale [Map], and Broughton [Map], have been most exactly surveyed by Mr. C. W. Dymond, F.S.A., and the plans and results of his consummate and critical examinations may be found in these volumes.1 Some of the less prominent prehistoric remains existing within our district, have from time to time been treated and delineated in a perspicuous manner by various members of the Society, (to which reference may be found below,) so as to leave nothing more to be desired.2

Note 1. Group of Cumberland Megaliths. Transactions of this Society, vol. v., p. 39. Gunnerkeld Stone Circle. Transactions, vol. iv., p. 537.

Note 2. Ancient Remains at Lacra and Kirksanton—J. Ecclestone, Trans. vol. i., p. 278

British Barrow at Hackthorpe.—James Mawson, - do. vol. ii., p. II

Buried Stone Circle, Yamonside.—M. W. Taylor. - do. vol. i., p. 167

Leacet Hill Stone Circle.—Joseph Robinson - do. vol. v., p. 76

Clifton Barrows.—M. W. Taylor, - - - do. vol. v., p. 79

Stone Circle, Gamlands.—Miss Bland and R. S. Ferguson do. vol. vi., p. 183

Stone Circles near Shap.— Canon Simpson - - do. vol. vi., p. 176

Archæological Remains in Lake District.—J. Clifton Ward, do. vol. iii.. p. 241

Cairns near Kirkby Stephen and Orton.—Canon Greenwell, "British Barrows," P. 381.

But still much systematic work remains to be done, in the determination and classification of some of the more obscure remains which are still left to us. There is still a field open for investigation and exploration. In many quarters may be traced the annular arrangement of sunken boulders, partially or wholly covered by the turf, occurring not only singly but in groups, marking the sites of buried stone circles. On our brown heath-covered moorlands there are many rings of stones and insignificant mounds, overgrown with ling and bracken, seeming unworthy of a passing glance, but which denote the burial places of a bygone race. On a lonely waste, lying high above the lower reach of Ullswater, on its right bank, there is a remarkable group of sepulchral remains, the existence of some of which has been comparatively unnoticed; and it shall be my endeavour in the following paper to give a precise description of these relics, and to classify them as I find them related to each other.

Travelling along the road from Penrith to Bampton, up the valley of the Lowther, we arrive at the little village of Helton. This was anciently called Helton Fleckett, and formed a portion of the manor of the Sandfords, the ancient lords of the pele of Askham Hall. This Helton affords a thorough type of an old Westmorland village: — severe and grey in aspect; the fields enclosed with walls of loose stones covered with moss and lichen, capped with the yellow stone crop, the rue-leaved saxifrage and polypody; the rough unkempt village green, with the limestone rock out-cropping here and there, and fringed with sycamores, the favourite shade-giving tree of the Westmorland homestead; little austere looking farmhouses, some of them two hundred years old, as may be seen by the dates inscribed over their doorways, with gables presented to the roadway, and their old rough barns and byres of greystone put together without mortar.

The valley is famous for its rich bits of meadow and its limestone-fed pastures, but above the village there is an enormous mountainous waste, which stretches away for miles over the fells which form the watersheds of Ullswater, Haweswater and Windermere.

An advanced spur of these mountains, separating the valley of the Lowther from that of Ullswater, is Barton Fell, and on it, just outside the higher inclosures of Helton village, there is an extensive plateau of heath and peat-moss; it is called Moordivock, or Doveack. It is 1,000 feet above the level of the sea. The old Roman road crosses this moor, and the surface of this ancient causeway is marked out by the short green sward which covers it, contrasting with the brown ling over which it runs, and the course of it may be traced for seven or eight miles along the crest of the ridges, proceeding over Kidsty Pike and High Street, where it attains an elevation of 2,600 feet. This was the Roman highway from the shores of Windermere through the vale of Troutbeck, pursuing its course to join the great York road over Stanemoor and the Eden valley at Brovacum, the camp at Brougham.

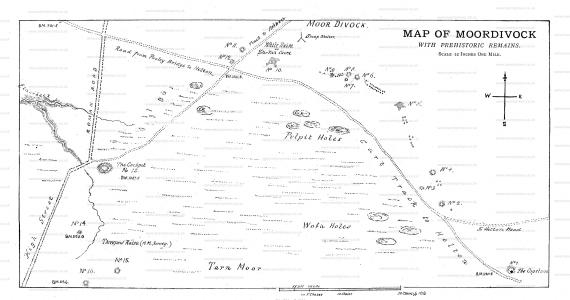

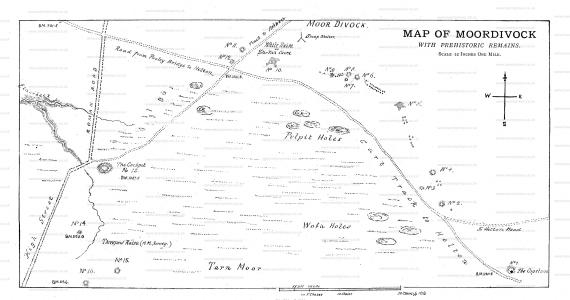

We leave the inclosures of Helton Head by a gate which opens on to the common of Moor Divock, and we perceive, to the right, a rough green cart track proceeding across the moor in a north-west direction to Pooley Bridge, which is the outlet of Ullswater. By the side of this road, about a quarter of a mile distant from the gate, and very near a guide-post erected at the junction of some tracks across the common, there looms against the sky a large single standing stone; it is called by those who frequent the place the Kop-stone, or, as some say, the Cock-Stone. It is the most southerly of the prehistoric structures which stud the area of this moor, and it would be most convenient to begin the description of these at this point. For the sake of clearness, they shall be referred to and numbered as they occur in succession, but I will divide them into two groups: — (A) stone circles lying to the right of road leading to Pooley; (B) stone circles on the left hand side or the south-west, near the old Roman road. The principal circles are illustrated by drawings made from actual measurements, and, except in one instance --the large circle of the "Cockpit"—on an uniform scale of twenty feet to an inch. The ground plans are so placed on the page that a vertical line through the centre points to the north; the number affixed to each plan refers to the number observed in the description; the erect stones are filled in with black, and the prostrate and overgrown ones are stippled or outlined. The map is enlarged from the six inch ordnance to the scale of twelve inches to one mile, and within its outskirts are included all the remains to be found on Moordivock, as described in this paper.

GROUP A. No i.—The Kop-stone. This monolith forms a prominent object, and may be seen for a consideable distance on the common. It stands in an erect position, and measures 5 feet out of the ground, and is about 14 feet in girth; it it not hewn nor dressed, but is a natural ice-borne boulder composed of one of the metamorphic rocks of the district. Although it now stands as a solitary object, this stone is a remnant, and was doubtless the most salient member of a prehistoric structure of a rather composite developement. Although not much besides the presence of this huge boulder may strike the observation of the casual passer-by, yet a little circumspection of the ground reveals traces of an environment of a low earthen ring-mound and excavated hollow, which encompasses a circular space, within the south-east boundary of which stands the monolith. The inclosed area is 57 feet in diameter. Outside the earthen ring, and from two to three yards outside the edge of the plateau, there has been an outer circle of set up stones, of which there are apparent about ten or a dozen in a circumferential position, though in a great measure sunk in the soil, and several others which may be probed under the sod-covered hillocks which cover them. The diameter of the outer ring may be estimated to have been about 76 feet. Along the margin of the inclosed plateau there are a considerable number of stones imbeded in the soil which may have formed an inner circle, and in three or four points along the boundary there are accumulations of loose stones, which seem to indicate the foundations of circumferential cairns. If such cairn structures occupied these positions, the similitude of the arrangement may be compared with that which obtains in the circles of Gunnerkeld [Map], near Shap, Eskdale Moor [Map], and other places, and also, as we shall presently see, in the circle of "Cockpit" on this moor.

In the plan No. 1 are shewn the site of the Kopstone, and the disposition of the surrounding stones and inclosed cairns, so far as the dislocation and partial effacement of the remains will permit. There are two round shallow pits within the area which I apprehend are merely disturbances of the ground from explorations long ago, but I know of no record nor tradition of any discovery within this circle. There is also a working down of the ground around the base of the monolith, but this probably may have been produced by the action of water, and by the treading of sheep which have been attracted to it as a rubbing-stone. There are no cup nor ring-markings on the Kopstone.

Proceeding along the cart-track leading to Pooley for about 300 yards, on the right hand side, we shall perceive the remains of another monument:-

No. 2.—Cromlech or Circle. This consists of one large boulder (a) fixed in the earth; it is 4ft. high and 14ft. 9 in. in circumference. About 4ft. space on each side of it, there are two upright stones, which are so placed as to form with it, an obtuse triangle, of which the point (a) forms the obtuse angle. The next stone (b) is 3ft. high out of the ground, and 3ft. gin. long: the stone (c) is eft. io in. high and 1 ft. broad. There are three other blocks which shew above the surface, lying in such a semicircular relation, as to suggest what might have been a circle of about 15ft. in diameter, but there are no cairn foundations nor elevation within the area. It is quite within reasonable supposition, that these three standing stones so closely adjacent, may have formed the trilithons of a cromlech, on which a ponderous cap-stone might have been poised. If such had ever been the case however, all vestige of the cap-stone has disappeared. In point of fact, throughout neither Cumberland nor Westmorland, is there any instance of a tripod dolmen or cromlech extant with its cap-stone in situ, although I know of some standing stones in groups of twos and threes, so related, that they may have possibly formed the uprights of dolmens. Judging however from the surroundings of this structure, it is more probable, that it consisted of a central monolith, with five or six stones forming the periphery of the circle.

No. 3.—Small Circle and Cairn. About fifty yards to the north of these remains, and about forty yards from a township boundary stone standing by the side of the roadway, there are to be seen the relics of what has evidently been a small stone circle and cairn about 11 feet in diameter. Some of the stones may be fixed and in situ, but it is difficult to judge how many are so placed, for it is manifest that the place has been rifled in a very rude manner, and several of the larger stones have been dislodged, and the smaller stones forming the pavement of the cairn have been scattered about, whilst there is still remaining the depression in the centre, where the digging had been carried on. This ruthless spoliation must have been perpetrated beyond twenty-five years ago, and before the conservative tenets which ought to regulate the pursuit of such diggings, and which it is the duty of archæological societies to promulgate, were recognized by these inconsiderate explorers.

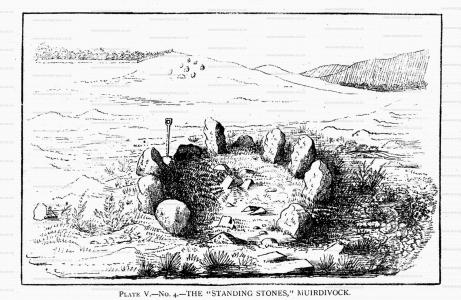

No. 4.—Circle. A little to the north of these remains, and about 120 yards from the upright stones, which I have called No. 2. and about 400 yards to the N.W. of the Kopstone, we arrive at a very perfect example of a small stone circle, with a single ring of stones, in a comparatively undisturbed state. This tumulus is marked on the ordnance map, and it is known as the "Standing Stones."

It is a charming little prehistoric gem in the way of a sepulchral circle. These lichen-covered boulders, standing in their pristine entirety, set up in their annular line, projecting their bossy outlines above the reedy grasses and heather of this desolate moor, appeal to us as the silent sentinels of the burial fires of a bygone race. The stones may be said to be eleven in number, eight principal erect stones, most of them about 3 feet high, and three smaller ones; they stand a little apart, some rather inclined outwards, and they inclose a space about 19 feet in diameter. There has been no outer circle here; but there are a number of loose cobble stones scattered about within and without the area, which renders it probable that the standing stones originally surrounded the base of a cairn. The site is on a knoll, probably partly artificial elevated about two feet above the level of the moor. This monument has moreover yielded up the story of its purpose. On May 30th, 1866, the exploration was made by Canon Greenwell, accompanied by Canon Simpson, the late Mr. Mawson of Lowther, and myself; and the proceedings were full of interest. A hollow depression was found in the centre, probably produced ages ago, by the weight of the heap of loose stones superimposed over the disturbed soil, in which the interment had been deposited. After digging cautiously to the depth of two feet under the surface, we came to a layer of fine sand, three inches in thickness, in which was placed a flower pot shaped urn, or food vessel, laid on its side, with its mouth to the west; underneath the layer of sand was found a deposit of the buried bones of an adult. The following is the description of the vessel given by Canon Greenwell. The Urn is 5½ inches high, 6 inches wide at the mouth, and 2⅝ inches at the bottom, which is slightly cupped. There are four unpierced ears at the shoulder. It Is very symetrically made, and the ornament is applied with great skill and delicacy. The pattern which covers the entire vase, including the lips of the rim, and the ears consists of encircling bands of short lines of finely twisted thong impressions, arranged herring-bone fashion. Both the bands and lines forming them are placed close together, and the general effect is very rich and at the same time tasteful. It is one of the best specimen of its class that I have met with, and nearly approaches in beauty, to that which I have referred to above as resembling it in shape (fig. 71) . In the hollow there were also found two fragments of another vessel.1

Note 1. British Barrows, p. 400.

The Stone Avenue. We proceed in a direction to the north-west, and at a distance of 89 yards from circle No. 4, we presently discern a number of stones set up, and projected from one to two feet above the tufted grasses and ling of the moor. After a little circumspection the observer can begin to trace a certain order and arrangement in double lines, in this series of stones. On one side it will be noticed, there are five stones, some set at the distances of 12 feet apart, others 20 and 27 feet apart, and on the other side there are two stones which might be said to represent the opposing line. After an intervening break of about 50 yards, always proceeding in the same direction, we again recognise a double alignment of six stones, three on each side, standing about 18 feet apart in the rows, inclosing a track of an average breadth of 20 feet. About twenty yards beyond this section of the avenue stand the remains of circle No. 5, the description of which will be deferred, until I have completed the notice of the remaining parts of this linear arrangement of stones.

At the distance of 18 yards from Cairn No. 5. always pointing in the same line, a little to the north of west, the disposition of the stones in double rows is readily discriminated. The two lines stand opposite and irregularly parallel, at distances varying from fifteen to twenty-four feet. In some portions of the rows, the stones are set as near each other as 6 feet apart, at other points they are 24 feet apart. On the north side, the stones are set rather closer than on the south; there are thirteen which may be counted on one side and eleven on the other. This alignment ceases about forty-five yards before we arrive at another group of dilapidated cairns and circles, which will be described as Nos. 6, 7, and 8.

But when we pass onwards a little beyond this group, we again encounter the track of the avenue, as represented by lines of five stones on one side and three on the other, standing more considerably separate, twenty yards or more, and describing rather a curve to join another small circle No. 9. Beyond this at the distance of 35 yards and again at 25 yards further on, there are two set up stones which stand as pointers in a single line to the White Raise or Star-fish cairn, No. 10, which is two hundred yards distant.

The artificial arrangement of these stones in lines, throughout the course I have described is perspicuously evident. The scheme apparently is denotative of an intention and attempt to mark out or link together in this kind of way the different groups of circles and cairns which were dotted over this moor. The object may have been nothing more than to indicate or bound the pathway from one grave circle to another. The stones in these lines may possibly have been more numerous than they are now, but they are not so large as those which compose the circles, and would certainly not be conspicuous at a distance over the level of the growth of ling on the common. The course which this trackway describes is not straight but involves curves from point to point, as might imply a design on the whole of the serpentine form. The extent of the line over which these stones may be traced is 540 yards, but there are breaks of continuity here and there in the vicinity of the circles.

I must now revert to the description of the other tumuli which are congregated on this spot. We set forth from the last interesting object described, the sepulchral ring of No. 4, and being guided by the line of stones, at the distance of about 260 yards, we approach the next remarkable structure.

No. 5. Circle (Star fish). There are three large stones in situ, which with some large prostrate ones, seem to have bounded an interior circle of 19 feet in diameter. The area within is level and slightly elevated above the surrounding ground. On the north side there is a great lichen covered boulder 4 feet long, 1 foot 6 inches thick, and standing 3 feet 6 inches out of the ground; it is supported on one side, at an interval of 3 feet by another stone 2 feet 7 inches high, 2 feet 7 inches long, and 2 foot 4 inches thich, and on the other side of it, 12 feet off, stands another boulder 2 feet high, 2 feet long, and 1 foot 3 inches thick; external to what may have been the inner ring, there is a great accumulation of loose stones forming an outer ring, of which the diameter might be 45 feet. The remarkable feature of this circle is, that from the circumference of this stony rim, there radiate three spoke-like projections, or prolongations of cairn structure, extending in a straight direction for two or three yards. This same arrangement of a cairn with what I may call these gibbous appendages will be better seen, when we come presently to investigate the more important monument in the group No. 10, or what I have called the Starfish Cairn. In No. 5, the same disposition of contour exists, as will be noted in the more prominent specimen No. io, but here everything is rather fragmentary and displaced, and it is difficult now to estimate with precision the outline of its constructive plan; the stones have been so scattered about, that the integrity of the structure has been much deranged. Fifteen years ago when I first made a survey and sketch of the remains, the aspect was much less dilapidated, than it is at the present day. An exploration was made here some years ago by Canon Simpson with the following results,

Opposite the largest of the stones, and in the centre of the circle, was found a deposit of ashes and burnt bones which had been inclosed in an urn. The stones forming the heap had been much disturbed, and the urn was broken, but when first discovered the rim was entire and measured 13 inches across. It was of the rudest manufacture, imperfectly burnt, and had been placed upside down.1

Note 1. By Canon Simpson, Pro. Soc. Antiq. Scotland, 1st series vol. iv. p. 443.

The best marked section of the stone avenue to which I have alluded, lies between this cairn, and the next group of three stone circles, which are placed about 170 yards from No. 5.

No. 6. Single Stone Circle. The disposition of the stones in this circle is well marked, there are seven of them in all, three or four of which, adjacent to each other, are upright and fixed. The plan represents a symmet rically formed single circle of 25 feet in diameter, the boulders have been set up on the ground in regular order to each other; there is no evidence of any pavement or cairn structure here, and the sod within the area, gives no indication of having been opened or disturbed.

No. 7. Double Stone Circle. This stands about thirty yards to the north-west of No. 6. It is safe to assume that this has been a double circle, but whether exactly concentric is difficult to ascertain, seeing that a considerable segment of the outer ring is wanting, but there are still of this ring five stones remaining, some considerably sunk down however, and their position would indicate the diameter to have been about 14 feet. Within this space there are six stones pretty well in their places, which might have environed an inner ring of about 6 feet io inches in diameter. I do not find that this circle has ever been opened or examined.

No. 8. Single Circle. Situated about six paces to the north of No. 7, there is a single ring of stones, of which seven are prominent along the circumference, and three more may be discovered projected as hillocks on the sod. They form a very small single circle of only 9 feet in diameter, without any stony pavement. Proceeding on in the westernly direction, we perceive another sweep of the avenue. Cropping above the heather of the moor, and at the distance of 60 yards we are led to ...

No. 9. Single Circle. The evidence of the circular arrangement here, is sufficient to enable us to determine the diameter to have been about 14 feet. It is an ordinary grave-mound circle. Near the centre there is a large prostrate stone, which shews a length of 3 feet 6 inches, and a thickness of 2 feet, and the position of eight stones may be made out along the circumference, three of them protruding above the surface and others grown over by the sod. About 250 yards from the remains of this circle, W. by N. we can readily discern the elevated knoll with the raised heap of stones, well known to the shepherds, and marked in the ordnance survey, which constitutes the next important sepulchral monument.

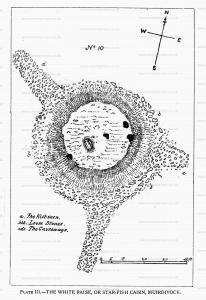

No. 10. The White Raise or Stay-fish Cairn. The site of this structure is on a slight natural eminence, which, with the accumulation of stones, which compose it, gives it an elevation of some seven or eight feet above the level of the surrounding surface. There has been heaped together a quantity of loose stones of every variety of sizes, for even some large boulders still remain, which appear to have bounded the base of the heap, and some which have formed an inner ring. The outside diameter may be said to be from 57 to 60 feet. It is almost impossible to define what the width of the inner ring may have been, as there are only three or four large stones remaining. In all probability there was an inner ring, and judging from what we see in the sister cairn No. 5. on this moor, and from what has lately been made out, in analogous cairn structures in the north of Scotland, this inner ring might have been about 25 feet in diameter. It was here and in Cairn No. 5, there was first described1 as long ago as 1868, that peculiarity of plan and contour, which I then designated the star-fish form, which distinguishes these examples, from so far as I know, all other English cairns.

Note 1. By the Author, Trans. Cumb. and West. Antiq. and Archæol. Soc. vol. i. p. 166.

From the shelving bank of earth and stones which composes the outer rim of the cairn, there radiate three causeways of loose stones, now rather flattened on the surface and but little above the level of the ground, one pointing to the S. one to N.W. and one to E. In two of these causeways the shape and outline are well defined, but in that to E. the formation has been considerably broken and demolished. The form and dimensions of these projections are the same, in both of those marked c and d on the plan, each being 32 feet long, with a medium breadth of 9 feet, but narrowing slightly towards the extremity. The stones composing the pavement are loose and of all sizes, and there do not appear to be any large fixed stones bounding the outline, nor set up at the extremity of the causeways. The line of axis of two of these spokes would pass pretty nearly through the centre of the circle, but that of the third spoke c would not pass through the centre, but would cut off a segment of the circle, so that it is not produced from a radius of the circle. There is no evidence of there ever having been more than three of these appendages. This monument is also notable, as exhibiting lying open to view at the present time, a very perfect example of a kist-vaen. This chamber was laid open and the discovery was made known about twenty-five years ago by Canon Simpson, and several entire bones of an adult were found lying in the cavity. The position of the kist is not in the centre of the circle, but a little to the S.W. of that point, and it lies about a foot below the present surface. The measurements of the cavity are 4 feet 3 inches long, 2 feet wide, 2 foot 7 inches deep, the sides are formed of slabs of the limestone of the district, set on edge in an upright position, and the ends are closed by blocks of a similar description. The lid is formed of a single slab, 4 feet 6 inches long, 3 feet wide and 5 inches thick. The plane of the kist-vaen has a direction N.W. and S.E. The body must have been deposited in a bent or doubled up position.

It is a curious circumstance which obtains throughout the burial ground area on this moor, and I think I have observed the same elsewhere, that the grave mounds are apt to be placed in clusters of three in point of contiguity. About a hundred yards to the N.W. of No. io, there may be found the remains of two tumuli adjoining each other.

No. 11. Boat shaped barrow. This is a humpy-backed tumulus composed mostly of earth; it is about 25 feet long and 15 feet broad at the centre, where it is about 22 feet high above the level of the ground: it is oval in outline, and may be described as boat-shaped, that is as a boat bottom upwards: the long axis is E and W. The western end is bounded by a large stone 4 feet 6 inches long by 3 feet broad: the sites of three other fixed stones may be discerned along the southern boundary, and three more at the east end, so that the probability is that the barrow was set round with stones.

No. 12. Circular barrow. Stands 50 yards to the S. of the last. It is a circular mound 15 feet in diameter, of heaped up earth and stones, the top of it is occupied by a quantity of loose stones, there is a hollow in the centre, where it seems to have been opened at some time for examination.

We will now proceed to the group (b), Stone Circles on the S.W. near the old Roman road. About a third of a mile from the White Raise, close by the point at which the old Roman road crosses the rill, which goes to form the Elderbeck, there is the following circular enclosure, which is marked in the ordnance map, as the remains of a Druidical Circle.

No. 13. Double Circle, "The Cockpit [Map]." This is a large prominent object, and it is well-known to those who frequent the common, under the name of the Cockpit. The remains are situated on a natural flattened ridge, and consist of a circular arrangement of boulder stones inclosing a flat area. It cannot be said to be perfectly circular, being slightly oval in circumference, the diameter N. and S. being go feet, and E. and W. 103 feet. As a plan has been furnished, (Plate IV), with the sizes of the principal stones given, and the distances between them, many of the details may be omitted in the description. A few of the stones are now doubtless dislocated from their regular bearings, some having fallen inwards and others outwards, but the observer can readily discern that there has been a carefully constructed peristylith of two rings of stones, an inner and an outer. Within the circumference there are the ruins of four segmental cairns or barrows. The most prominent of these is situated within the boundary on the E. side, where an earthern mound has been raised above the level of the plateau, and a circular cairn has been set upon it. The diameter of this heap is 24 feet, and the circular form is well maintained by stones averaging a foot square, of which about 70 remain, set in an approach to concentric arrangement. The circle at the foot of figure 1, consists of eight or ten stones in their places, and has a diameter of g feet. The cairn situated under figure 16, is flattened and nearly demolished; that under figure 15, shews the cairn structure piled up with loose stones, and so elevated above the surface.

Here then we have exemplified one of the Cumbrian great 100 feet circles, shewing the distinctive peculiarity of segmental cairns, and indeed composing a monument of considerable magnitude and importance in an archæological sense. Hitherto the knowledge of this relic has been confined chiefly to the dalesmen of the neighbourhood; concealed in its remote position, it has been out of the sight of and neglected by visitors, save by the ordnance people and a very few antiquarians, and no plan or description, so far as I know, has ever been given of it, except in a brief note by the late Mr. Clifton Ward.1 About 250 yards to the S of the Cockpit there are the remains of a group of three or four tumuli, standing about 100 yards apart, which require just to be noticed in closing this description of the sepulchral remains on Moordivock.

Note 1. Notes on Archæol. remains in the Lake District, by J. Clifton Ward, E.G.S. Cumb. and West. Archæol. Trans. vol. iii. p. 241.

No. 14. Is a circular space raised about a foot above the surface, and 27 feet in diameter; with a double circle of stones, the larger ones inside and the smaller ones outside, but quite in a grass grown condition. It has evidently never been opened.

No. 15. Is a mound similar to the last but of smaller size, only 15 feet diameter; in the centre there is a large blue cobble boulder, which has been split; it is 3 feet long. There has been a digging near this stone.

No. 16. A grass-grown artificial mound, but without any large stones. There are two or three other elevations close by which seem artificial, and to represent circular grave mounds of about 15 feet in diameter.

Remarks. From the multitude of the relics still existing, it is evident that this locality was the necropolis or burial ground of the tribe or head families of the tribes who occupied the neighbourhood. It is doubtful however whether these people had their habitations on this spot. There are no remains to be found on this elevated area of their hut circles or bee-hive wigwams, but lower down near the lake, on the farm of Crossdormont (Tristermont), I think I have made out lines of village entrenchments which betoken old occupation. But the great stronghold of these septs was doubtless the fortified oval camp which crowns the summit of Dunmallet1, the conical hill which guards the outpour of the lake at Pooley Bridge. Traces of another burial ground of these septs in this locality, I, in a manner, stumbled upon a few years ago at Yamonside; they comprise an extensive four-ringed stone circle, now very much sunk in the ground, and nearly buried, situated in a river holme by the side of the Eamont.

Note 1. Old pronunciation Dun Mawland; (Hiberno Celtic) Dun Meallan, the hill of the pile; Meallan, diminutive of Meall, a heap or mound. The derivatives from Meal', and Meallan are found chiefly to be applied to conical eminencies of hills; as Dunmallet (Dun Meallan) great and little Mell Fell (Meall), Dunmaile (Meall) Dalmellington (Meallan), Mailing, Melling, (Meallan). It is curious to observe that in all the instances I have given, there is a conical eminence which has been surmounted by defensive entrenchments.

These vestiges have already been described in the pages of these Transactions.1

1. By the Author, Trans. Cumb. and West. Arch. Soc. vol. i. p. 162.

It may be safely assumed that all these sepulchral remains on Moordivock were erected by the same race of people, and belong pretty nearly to one epoch. The internal evidence to justify this presumption is derived from a consideration of the subordinate design which seems to have prevailed in the erection of these structures. It is trivial to speculate where the first tumulus was reared, or around what particular circle the first funereal obsequies may have been initiated. Most likely memorials would be raised as the requirements arose, in succession of time, it might be over several generations; but these stone avenues leading from one cluster to another, imply an attempt to carry out a premeditated and uniform principle and custom in these arrangements. Yet although all these erections may be referred, without hesitation to the same epoch, nevertheless they exhibit much variety of type and style in their formation, as well as in the manner of the disposal of the dead.

1st. Variety in the Interments. For instance an exploration of the circle No. 4. disclosed a deposit of burnt bones lying in the soil, accompanied by a food vessel; in cairn No. 5. the calcined bones and ashes had been held in a mortuary urn; whilst under the White Raise or No. 10. there was found inhumed in a stone coffin the whole skeleton in a doubled-up position.

The same story is told by Canon Greenwell and other barrow explorers, that burial by inhumation and by cremation was coeval, and was practised by the same people at the same period of time, and that the two modes of sepulture had been found existing in the vicinity of each other, or even under the same superincumbent barrow.

The recent discoveries in the neighbourhood of Penrith, in respect to the contents of prehistoric graves, indicate that in this part of the country at least, the usage of cremation and that of inhumation and cist burial were practised indiscriminately. Under the Redhill sculptured stone1, I found the cremated remains without an urn; at Moorhouses the calcined bones in an urn; within the Leacet circles2 as described by Mr. R. S. Ferguson, and Mr. Joseph Robinson, the interment had been by cremation, and there were found five cinerary urns, a food vessel, and an incense cup; whilst under the Clifton barrow we had two kist-vaens with unburnt skeletons in company with their food vessels.2 great 100 feet circle No. 13. or the 'Cockpit,' there is a higher development, which brings it into association with some of our most important megalithic monuments. Along and within the circumference of the big inclosure, there are four subordinate segmental sepulchral circles. So we find the great 100 feet Keswick circle, to contain in the same manner on its eastern side an accessory stone inclosure, and also the site of a circular barrow; the 100 feet circle at Eskdale Muir [Map] includes within its ring five circular tumuli; the 100 feet double circle at Gunner-keld [Map], has within its inner belt a segmental chamber; the same feature is presented by the analogous circle at Oddendale [Map] near Shap.

Note 1. Trans. Cumb. and West. Arche ol. Soc. vol. vi. p. no.

Note 2. Ditto. vol. v. p. 77.

Note 2. Ditto. vol. v. p. 90.

The Avenues. One noteworthy result of a close scrutiny of these remains on Moordivock, has been the demonstration of the system of stone alignments connecting the different groups of sepulchral circles, which has been referred to in the general description, and the course of which may be seen plotted out in the chart. I have called them alignments, but in fact they are for the greater portion of their distance double rows of stones, and they have no doubt been in double rows, from the Kop-stone to their extremity, so that the appellation avenue is more correct, and may be more appropriately employed. The presence of such avenues in connection with sepulchral rings is of course well known to archæologists, and we may with propriety include the Moordivock group, within the class of monuments, which have been distinguished by this peculiarity. It is worth while therefore, to consider cursorily, as to the prehistoric congeners in Great Britain which may be found in the same category, and to what extent our Moordivock remains approximate to, or may be indentified or contrasted with them.

Beginning with the Cumbrian groups, the first example to suggest itself, is of course the neighbouring and at one time magnificently expressed Shap avenue. Variedly described by the older antiquarians, by Camden, Pennant, Stukeley, and others, this remarkable line of megaliths, has received the fullest history that its condition in the present century has permitted, from our president Canon Simpson. Suffice it for our present purpose to say, that this line of huge boulders has formed a connecting link between a number of circles of considerable dimensions, probably sepulchral, the head of it beginning at a stone circle a quarter of a mile to the S. of Shap by the railway side, then to the circle at Karl Lofts, then past another circle at Brackenber, and on in a N.W. direction to the village of Rosgill, a distance of three miles. Long ago it used to be maintained by the old people in the neighbourhood, that this line of stones extended to Moordivock —to the very locality about which we are now engaged, which is as the crow flies about 7 miles from the S. end of Shap they said that the Kop-stone on Moordivock lines with the Goggleby stone and Karl Lofts. I know this ground well, and have tracked the line as far as Rosgill, but I have failed to detect any standing stones of such dimensions, that they could be said to define the line between Rosgill or Knipe Scar and Moordivock. It must be remembered, that a valley of considerable depth has been hollowed out between these points, filled at one time by a glacier, and now giving passage to the river Lowther, and moreover that there are stones everywhere without number, as the whole country is strewed with the boulders of the drift of the ice sheet. Enough however has been said to shew, that the same idea which impelled the gigantic labours of the avenue builders at Karl Lofts, in linking together their sepulchral structures by rows of stones, obtained a manifestation in a more humble degree on the hillside of Moordivock, so as to warrant the association of the two in the same class of prehistoric works.

Remnants of former alignments of megaliths may still be made out elsewhere, in various localities in the district around Penrith, a few appearing as Standing Stones, and some partially sunk, or walled into the breast of fences. For instance in the direction from the S. end of the village of Newton Reigny, by Mossthorn, on over Pallet Hill to Newbiggin ; also from Sewborrens over the Riggs farm to Newbiggin some few exist, and I have seen old people who remembered the removal of many of these stones at the beginning of this century. These lines may have been in connection with the barrows and stone circles, of which the dilapidated remains and half buried relics are frequent over this locality. I have noted also a line of stones from a cairn on the Lowther Woodhouse farm, marching by Yanwath wood, and in a number of other places which need not be referred to further. According to the old antiquarians, in connection with the important monuments at Avebury, there was an extensive development of the avenue system. From the outer vallum of the great 1200 feet circle two stone avenues extended, one pointing with a slightly double curved line south-easterly for 1430 yards in the direction of Kennet, where it ended in another double circle ; another similar one was spoken of by Stukely, as the Beckhampton avenue. There is another double circle within the Avebury group at Hak-pen hill, which was said to have had an avenue extending for a quarter of a mile pointing to Silbury hill [Map].

In the rear of the group of cromlechs near Aylesford on the Medway, known as Kyts-cote house and the Countless Stones, there extended at one time a line of stones for three quarters of a mile pointing towards another group at Tollington. Also on the left bank of the Medway, about five miles from Aylesford in the park at Addington, an avenue of stones existed in connection with two stone circles standing in that place.

Again at Stanton Drew in Derbyshire, there is a group of stone circles ; one very large one of 378 feet in diameter, one smaller one of 96 feet, and another of 129 feet. Proceeding from the two former circles which are adjacent to each other, there are two straight avenues extending to a distance of somewhat under 100 yards.

The parallel lines of stones which are so well seen amongst the remains on Dartmoor, particularly near Merivale bridge, connecting the different groups of circles with each other, are quite after the fashion of the Moordivock examples, in fact the similarity is very great, only the width of the tread is narrower in the Dartmoor avenues. Closely allied also to the type of the Moordivock avenues, are the monuments at Callernish in the Isle of Lewis. Here we have a single circle 42 feet in diameter, from the centre of it a double row of stones extends in a north-easterly direction for 294 feet, consisting of 9 and io stones in each row at a width of about 20 feet. From the opposite side there proceeds a single row, to the southward, of half a dozen stones to a distance of 114 feet, whilst crosswise from the circle E and W, there extends a single line of stones measuring 130 feet across the whole.

Whatever may have been the object of parallel arrangements of stones in connection with sepulchres, the idea has received its greatest development in the remarkable works, of which we see the remains on the plains of Carnac in Brittany. There are two great alignments of stones, one at Maenec, and the other at Erdeven about two and a half miles distant ; the one extending for about two miles, the other about one mile. These great works consist of ten or eleven parallel rows of stones set regularly, diminishing in size and becoming more sparse as they approach the extremity. There are other smaller and shorter avenues of a similar kind on the place, which is studded with megaliths, dolmens, tumuli, and long barrows, many of which are connected together by these rows of stones. Whoever studies the scheme of the plain of Carnac, and views the juxtaposition and relation of these stone rows, with the prehistoric sepulchral structures there, cannot but recognize in these works, the supreme amplification of a product, of which the rudimentary pattern may be found on our Westmorland hillsides.

The Star-fish Cairns. Although these cairns only afford three rays or projections, I have ventured to give them the above designation. A star-fish of course has five radial arms, but they are often found in nature with three only, having suffered from the accidental loss of two ; and such a mutilated specimen of an asteroid or an oreaster would typify very nearly the shape of one of these cairns. The first notice of the fact of the existence of this form of cairn, was given by me in a short account of these remains in a paper to this Society in 1868.1 At that time the occurence was perfectly singular and unique, and I am not aware, that since then any other examples have been described as existing in England. However a remarkable verification of the same form of cairn structure was brought to light about five or six years ago in Scotland.

Note 1. 'On the vestiges of Celtic Occupation near Ullswater.' Trans. Cumberland and West. Archol. Soc. vol. i. p. 154.

The plain of Clava in the Nairn near the battle field of Culloden, is strewed with the relics of tumuli ; so numerous were they, that it would seem that the whole valley, like the plateau of Moordivock, had been a great central burial ground to the prehistoric cairn builders. The most prominent of these remains consists of a group of three circles, situated at Balmaran of Clava, and these have attracted a good deal of notice and discussion lately amongst Scottish antiquarians, in connection with the cup-markings which abound on some of their stones. But what concerns us at present is the circumstance, that one of the cairns constituting the middle member of this group, has been found to present the peculiar feature of three spoke-like projections, which identifies it in form with the star-fish cairns on Moordivock. It would seem, that the surfaces of these causeways were brought into view during recent clearings and restoration by the proprietor, and that the first published notice of the discovery was given by Mr. William Jolly in a paper on the cup-marked stones found in the neighbourhood of Inverness.1 A more detailed description with a plan has since been given by Mr. James Fraser in a paper 'On Stone Circles of Strathnairn and neighbourhood.'2

Note 1. Proceed. Soc. of Antiq. of Scot. 2nd. S. vol. iv. p. 306.

Note 2. Proceed. Soc. of Antiq. of Scot. 2nd. S. vol. v. p. 347.

The monument at Clava consists of a three ringed circle, the intermediate ring inclosing a cairn-like structure of loose stones ; from the circumference of this there radiate three causeways or projections, about seven feet in width, composed of small stones, and extending to fixed stones which mark the boundary of the outer circle. So far as I can ascertain, this is the only example of the variety of star-fish cairn which has been found in Scotland. The great horned cairn of Caithness, as described by Mr. Anderson1, is another departure, and may be esteemed a modification of the star-fish form, with four projections instead of three, or like some species of asteroids with one radial arm wanting.

Note 1. 'Proceed. Soc. of Antiq. Scot.' 1st. S. vol. vii. p. 480. et seq.

At Clava the diameter of the intermediate ring is 57 feet, which corresponds exactly with the sizes of the two starfish circles on Moordivock. But at Clava, there is an outer ring of 107 feet in diameter, composed of eleven stones now existing, and it is to one of these outer monoliths, that each of the three projecting causeways radiates, one to the S. one to the E. and one to the N.W. The length and breadth and character of the pavement of these causeways, are precisely similar to what appears in the Moordivock cairns, where however there is no equivalent to the outer ring of boulders which exists at Clava. I have looked over many of the stones on the Westmorland moor, but have not succeeded in finding any of the sculpturings and carvings which are so frequent on the boundary stones of these Clava circles. These mysterious archaic toolings do however occur in our district, as on the face of the mênhir of Long Meg, on one of the monoliths of the Shap avenue, and also on the Maughanby and Red Hill stones now deposited in the Penrith museum.1

Note 1. The author in Transactions of this Society, vol. vi. p. i 13, and in Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 2nd. S. vol. iv. p. 438.

The question naturally arises, what may have been the object or final purposes of those radiating adjuncts in this species of cairn. The simplest conjecture which occurs to me, is that these causeways were projected from the centre and affixed as marks to divide the circle into segments, each of which might have been devoted to sepulchral uses for separate members of the tribe or family. We can hardly imagine, that this complicated form of burial mound was devoted to a single grave, it is more probable there were multiple interments therein. But further exploration would be necessary to determine this point.