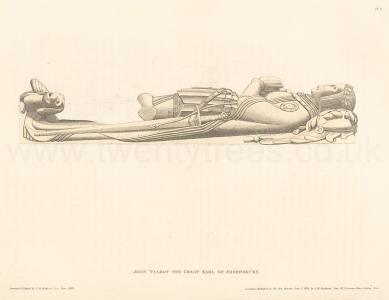

Effigy of John Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Effigy of John Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

WHAT English spirit, even in these latter days, but rouses at the name of Talbot!

"The cry of Talbot, serving for a sword!

--" The scourge of France!

The Talbot so much fear'd abroad.

That with his name the mothers still'd their babes."

John Talbot was the second son of Richard Talbot, by Ankaret le Strange, and was born about the year 1380. He married Maud, the daughter of Thomas Nevill, Lord Furnival; and soon after the accession of Henry the Fifth to the Crown we find him deputed Lieutenant of Ireland, by the title of Sir John Talbot, Lord Furnival. In 1417 he was one of the leaders in that great armament of 25,000, men, with which the King in person, attended by many nobles of the land, passed the seas, landed in Normandy, and laid siege to Caen. In 1428, the Duke of Bedford being Regent in France, he was with the Earls of Salisbury and Suffolk at the siege of Orleans, where the Earl of Salisbury was slain by a cannon shot while he was looking through the iron-gratings of an oriel window. In the following year, the siege of Orleans was raised by the celebrated Joan of Arc, styled for her fanatical pretensions La Pucelle de Dieu. This gave a temporary turn of success for the French cause; and Talbot, retreating before a superior force, was wounded and taken prisoner at the battle of Patry. He was ransomed about four years after for a large sum of money, and the enlargement of Ambrose de Lore, a French officer of high repute; and he immediately resumed and continued his military exploits in the French territory, with the most active valour, and commensurate success.

In 1441, by the Kings letters patent, dated 20th March, he was created Earl of Shrewsbury. In 1444 he was again Lieutenant of Ireland. His honours were increased by the dignity of Earl of Waterford. Sir John Talbot, his son, was also constituted Baron Lisle.

The English cause declining in France, the Earl of Shrewsbury was appointed Lieutenant of Aquitaine, and it was resolved that he should attempt the recovery of that province. In 1453, he diligently superintended the fitting out of an armament, with which he set sail, and landed in the peninsula of Medoc, on the coast of Gascoigne. He took the strong town of Fronsac, and advanced to Bordeaux, which the citizens yielded to him by a concerted plan, unknown to the French garrison, who were taken by surprise. The Earl of Shrewsbury, having established himself in Bordeaux, applied himself to the reduction of the strong places in the neighbourhood, and, among others, took the castle of Chastillon, in Perigord, in which he placed a garrison.

The King of France assembled an army of 22,000 men, and divided them into two bodies, one of which he committed to the Comte de Clermont, directing him to march upon Bordeaux. Of the other he retained the command himself, and despatched two Marshals of France, with 1,800 men-at-arms, with their proportionate number of archers, making together 7,200 men, to the siege of Chastillon, before which place they posted themselves in a strongly-entrenched camp. The experienced Earl of Shrewsbury, seeing the danger of being hemmed in between two armies, resolved to engage them in detail, and promptly marched to the relief of Chastillon, driving a strong advanced detachment of the French before him.

The French had conveyed to the siege of Chastillon the whole royal park of artillery, under command of the Chevalier Jean Bureau, the Master of the Artillery. Seven hundred labourers attended him to place the guns and bombards, and construct field-works. The French drew these engines of destruction within the trenches of their camp, loaded, and pointed them towards the quarter from which their enemy was advancing. The venerable Earl of Shrewsbury, then eighty-seven years of age, mounted on an easy hackney, accompanied by Lord Lisle, his son, Lord Moleyns, and eight hundred horse, approached the enemy's post before the dawn of the 7th of July, 1453. He halted for the infantry in his rear, about four thousand, to come up, and ordered a pipe of wine to be broached to refresh his companions, fatigued with the weight of their armour and a rapid march. The French retired with affected precipitation within their intrenched post. The veteran Shrewsbury ordered his lances to dismount, and carry the place at once by storm. St. George's banner, the royal banner of England, the banner of the Trinity, his own, and those of his noble companions, were advanced. The storming- party marched forward with determined resolve to the entrance of the camp,—when on a sudden the death-precursive suspense was broken by the vivid flash from dense and rolling columns of grey smoke, the thunder-peal, and bolts resistless (ploughing up the ground, and sweeping all opposition from its surface) from the three hundred pieces of artillery, with which the lines appeared, on the instant, as by some enchant- ment, to be bristled.

The old Chronicles relate an affecting scene between the elder Talbot and Lord Lisle his son. They say, the net into which he had been drawn did not escape his experienced eye, and he counselled his son to a retreat, as he was but a young soldier, stranger to the honours of the held, while for him to turn his back would not only stain all his former laurels, but fill his companions in arms with dismay and despair. The son of Talbot, both in lineage and heroic soul, rejected at once this counsel, and they fell together. Thus Shakspeare:

"Thou antic. Death! who laugh'st us here to scorn.

Anon from thy insulting tyranny

Two Talbots, winged, through the lither sky,

In thy despite shall scape mortality."

The particulars of the elder Talbot's end may be gathered from Hall and Monstrelet. A ball from a culverin killed the hobby on which he rode, and as he lay extended on the ground in the weakness of age, some base and cowardly hand shot him through the thigh with a hand-gun. He died on the held. His body was conveyed to England, to his manor of Whitchurch, in Shropshire, where it was buried in the parish church under a monument erected in the chancel, with this epitaph:

"Orate pro anima præenobilis domini, domini Johannis Talbot, quondam comitis Salopise, domini Furnivall, domini Verdon, domini Strange de Blackmere, et Mareschalli Franciæ, qui obiit in bello apud Burdeux, viio Julii, M.CCCCLIII." [Pray for the soul of the precious Lord, Lord John Talbot, Earl Shrewsbury, Lord Furnivall, Lord Verdon, Lord Strange of Blackmere, and Marshal of France, who died in was at Bordeaux July 1453]

Talbot, after the death of Maud, whom we have mentioned, married a second wife, Margaret, eldest daughter and coheiress of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. She survived till the year 1468, and was buried in St. Paul's cathedral.

Speed tells us that, with characteristic bluntness, Talbot had caused these words to be engraven on the blade of his sword: "Sum Talboti. Pro vincere inimicos meos [I am Talbot. For defeating my enemies]." A motto which it was the purpose of his life to verify in his country's cause. A profile and front view of his effigy, which has been sadly mutilated, are given. The face, as far as we can judge from its fractured condition, possessed fine character. This may be inferred from the front view; the wrinkled forehead and sunk cheek of age are ably expressed by the sculptor. The Earl wears the mantle of the Garter, of which he was a knight. The tassets of his armour and cuisses are fluted. The greaves are broken away. His feet rest upon a couchant talbot, or houndam

Note a. The history plays are generally very faithful versions of our national Annals. In the hrst part of the history play of Henry VI. a romantic scene is introduced between Talbot and the Countess of Armagnac, who invites him to her Castle as a visitor, in order to entrap him, and then declares, with many taunts, he is her prisoner. (See Henry VI. Part 1.) Talbot laughs at this announcement, tells her she has but a small portion of Talbot in her power, his sinews are not there, winds the bugle by his side, his men appear, and the tables are turned on the lady. We have not found the authority for this scene, but there is little doubt but in history or tradition it had some real existence.