Transactions of the Woolhope Club 1900 Arthur's Stone

Transactions of the Woolhope Club 1900 Arthur's Stone is in Transactions of the Woolhope Club 1900.

Arthur's Stone [Map], Dorstone. By H. Cecil Moore.

For previous remarks on Arthur's Stone, see the paper by Mr. Piper in Transactions 1882, page 175. Subsequently to the visit of our Club to Arthur's Stone, and whilst the Volume of our Transactions is in the press, circumstances have called more than usual attention to one of our most ancient megalithic monuments, viz., Stonehenge (Saxon Stán-henge, the hanging stones). The dislodgment, in the latter part of December, 1900, of one of the capstones of a trilithon in the outer circle, has led to certain protective work being carried out and to the placing of the well-known "leaning stone" of one of the tallest separate trilithons in an upright and thoroughly secure position. This newly-erected colossus is about 21 feet in height, and the portion of stone underground measured 8 feet. In the work of excavation stone hammers, heavy mauls for rough dressing the stones, and chips were uncovered, and not a single metal tool of any kind was discovered, indicating so far that the stones were erected previous to the bronze age. From thousands of other finds in England the bronze age is placed between 1800 and 2000 B.C. Moreover the character of the mauls, heavy hand instruments, unpolished and not fixed in handles after the manner of neolithic instruments, is suggestive of Old Stone Age rather than Neolithic implements.

On the theory that Stonehenge was built and used by sunworshippers, the fascinating problem of its age has been recently attempted by means of astronomy, by the orientation of an upright stone, known as the Friars' Heel Stone, as the rising sun is viewed over its summit on June 21st (the day on which the sun reaches its most northerly position), from the Altar Stone within the innermost elliptical enclosure. Sir Norman Lockyer, director of the Solar Physics Laboratory, South Kensington, and Mr. F. C. Penrose, antiquary, assisted by Mr. A. Fowler and Mr. Howard Payn, have given to the public the result of their calculations, allowing for the deflection of the sun in the present day at sunrise on 21st June from its old position, and based upon tables of the obliquity of the equinox. The number of years accounting for such shift of position amounts to 3,581 (with an admitted possibility of error in either direction of 200 years), which give the date of 168o B.C. See Nature, November 2 I St, 1901, page 55 ; and for explanatory illustrations see The Sphere, July 6th, 1901, pages 14 and 15, and January 4th, 1902, pages 26 and 27.

History does not help us in any way towards the solution of the age of Stonehenge. The earliest direct allusion to it which I can find is given in "Wanderings of an Antiquary," by Thomas Wright, 1854, page 296: namely, in a Latin list of "The Wonders of Britain " (De Mirabilibus Britannix), published by the historian Henry of Huntingdon, in the first half of the twelfth century. No definite mention of the remarkable area of great stones of Carnac in Brittany is made by Caesar or his successors during the more than four hundred years Roman occupation of Gaul. The Via Badonica passed by Silbury Hill, close to Avebury, yet there appears no comment upon this artificial mound by Tacitus, the intimate friend of Agricola, the Roman Ruler of Britain. The deviation southwards at Silbury Hill of the ancient Roman road from Bath to Marlborough, indicates that the mound was constructed before the Roman occupation of our island. Silbury Hill is 13o feet in height, 552 feet in diameter, 1,657 feet, nearly one-third of a mile, in circumference, and covers an area of five acres. It is formed of chalk rubble, and is probably the largest artificial mound in Europe. In Asia Minor the tomb of Halyattes, about double the size of Silbury, is given as the largest artificial mound known.

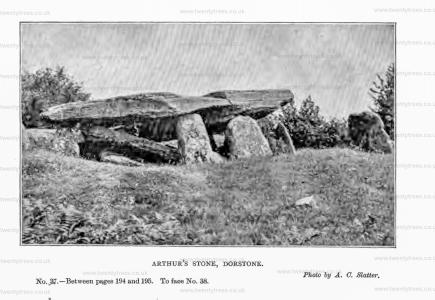

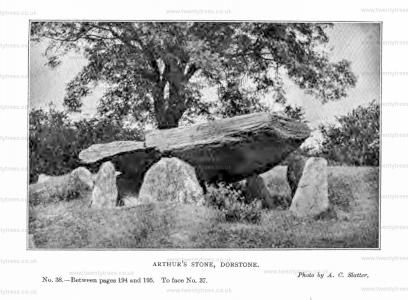

Arthur's Stone is not recorded in the first English editions of Camden's Britannia, which was published in 161o, nor is it marked in Speed's Map, of that date, but it is described in Nathaniel Salmon's work, published in 1728-1729, under the title of " A New Survey of England, wherein the defects of Camden are supplied and the errors of his followers remarked." Consequently we entertain no hopes of ever learning its age, or its origin ; moreover the cause of its nomenclature is purely a matter of conjecture. Its appearance suggests its being contemporaneous with other monuments in our island, such as Kit's Cotty [Map] or Coity House, in Kent, near Aylesford ; or with the standing stones at Avebury and elsewhere. It was probably erected centuries before the time of Arthur, and got subsequently named after the hero.

The name of Arthur has been so fully treated in legends that the distinction between the real Arthur and the legendary Arthur has been a long study. The hero Arthur was one of the last of the Celtic Chiefs in Great Britain, a leader of the Celtic tribes of the West of England against the Saxons, and the long resistance of these Western Celts was conducted under Aurelianus Ambrosius and Arthur. He is said to have been slain in the battle called by historians the Victory of Mountbadon, near Bath, 52o A.D. Again, under the same period of the 6th century, he is considered as a leader of the northern Cymry of Cumbria and Strathclyde against the Saxons of the east coast (Bernicia) and the Picts and Scots from beyond the Forth and Clyde. Arthur figures in the poems of the Cymric Bards, Merlin, Taliessin, Aneurin, and Llywarch Hen, all connected with the north. He figures in five of the poems, not as a southern King, but as a Guledig or " Dux Bellorum," whose twelve battles are in the north. It is impossible to reconstruct a coherent historical picture of this hero of the Welsh Tales, from the chronicles of Geoffrey of Monmouth, and the Romance of the Round Table. Before his final French form in the Romance of the Round Table, he was a Celtic hero in the Breton, and more specifically still in the yet earlier Welsh legends. From the above summary of a long article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th edition, 1875, we may consider the Arthur-land as extending from the Forth and Clyde, or rather, from the Grampians in Scotland to the Loire in France, and including, besides the South of Scotland and the North of England, Wales, Somersetshire, Cornwall, and Brittany. This leads to the question: Was the migration of Arthurian traditions from the south to the north, or from the north to the south ?

The Welsh people, especially in earlier years, were well endowed with the powers of imagination and fancy, faculties which have played a great role when combined with a certain kind of faith. From this combination (see " The Welsh People," by John Rhys and David Brynmor, 1900, chapter xii., page 592,) " there sprang up among the Brythons of yore a spirit of romance, which held the Europe of the Middle Ages bound, as it were, under a spell. There is no great literature of the Continent which does not betray the influence of the Brythonic hero Arthur, whom his people as late as the time of Henry II. expected to see returning from the Isle of Avallon, hale and strong, and longing to lead his men and countrymen to triumph over the foe and the oppressor. So real was the sanguine expectation that it is supposed to have counted with the English King as one of the forces which he had to quell in order to obtain quiet from the Welsh. So the monks of Glastonbury proceeded to discover there the coffin of Arthur, his wife, . and his son. This was to convince the Welsh, of the unreasonableness of their reckoning on the return of Arthur, who had been dead some six hundred years. The Welsh, however, went on believing here and there in the eventual return of Arthur ; and in modern times a shepherd is now and then related to have chanced on a cave where Arthur's men are sleeping in the midst of untold treasure, awaiting the signal for their sallying forth to battle. This is located in various spots in Wales, as also in the Eildon Hills, near Melrose, in South Scotland.

Similar expectations have been connected in Ireland with the names of several of the heroes of local stories current in that country. Take, for instance, the O'Donoghue, who is supposed to be sleeping with eyes and ears open beneath the lakes of Killarney, till called forth to right the wrongs of Erin, or of the unnamed King, who sleeps among his host of mighty spearmen in the stronghold of Greenan-Ely, in the highlands of Donegal, awaiting the peal of destiny to summon him and his men to fight for their country."

We are wont to call Arthur's Stone a Cromlech, a term exclusively employed in France, and on the Continent generally, for such monuments as we in this country use for the descriptive name of " stone circles," or " circles of standing stones," as at Avebury, Stonehenge, and elsewhere. " The restricted sense in which the term has been applied in recent times in this country has given rise to the notion that a " Cromlech " or great stone supported on props of smaller size, is a species of structure complete in itself, and distinct from the " dolmen " or chambered cairn.

Mr. Ferguson in his recent work on " Rude Stone Monuments" has described the monuments usually known by the term cromlech as "free-standing dolmens," and maintains that they were never intended to be covered with a mound or cairn. It is evident that the removal of the loose stones of the enveloping cairn would leave its megalithic chamber exposed as a cromlech, and undeniable that many of the examples adduced as " free-standing dolmens," in England, do exhibit traces of such removal .......

" On the other hand the steendysser or " giants' graves" of Denmark and Sweden, which are perfectly analogous to the Cromlechs of this country, are never wholly hidden in the mounds which envelope their bases.

"The present tendency is towards the entire disuse of the term cromlech, and the adoption of the term dolmen for all the varieties of tombs with megalithic chambers, whether " free-standing," or partially, or wholly, enveloped in mounds of stones and earth."—Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th edition.

The various kinds of ancient stone memorials are pleasantly treated on pages 159 to 173 of " A Book of the West," Devon, by Baring Gould, 1900, from which the following summary has been compiled:-

Of Dolmens there are numerous fine specimens in Cornwall, a single good example is at Drewsteington ; and in Wales and Ireland they abound. The Dolmen belonged to the period before bodies were burnt, it has usually a remarkable footstone, or a cavity, at one end for the introduction of a fresh corpse when required.

The Kistvaen, or stone chest, is usually of later date than the Dolmen. When burning of bodies became customary the need of large mortuary chapels or tombs as the Dolmens ceased. Some Kistvaens may have been erected for single bodies. On Dartmoor there are hundreds of Kistvaens.

Cromlech is the name applied by the French to "Stone Circles." So far as excavations have been made on Dartmoor no interments have as yet been found in them ; but interments have been found at the foot of several of the monoliths in the great circle of Pen-maen-mawr.

The Stone-Row is almost invariably associated with Cairns and Kistvaens, and clearly had some relation to funeral rites. In Scotland they are confined to Caithness. The finest are at Carnac in Brittany. Dartmoor is rich in stone rows. The most remarkable row is near the Erme Valley, which, starting from a great circle of upright stones, extends for 21 miles.

The Menhir, or tall stone, is a rude unwrought obelisk. There are several on Dartmoor. The highest, 18 feet, weighing 6 tons, is at Drizzlecombe.

Cairns, or Cams, a mere pile of stones, are numerous on Dartmoor, but all the large ones have been opened and robbed at some unknown period. Cairns are common in Ireland.

Recently, and since our visit to Arthur's Stone, a work by T. Cato Worsfold, has been published under the title of "The French Stonehenge," with numerous illustrations of the principal megalithic remains in the Mosliham Archipelago, so wonderful for their variety and quantity, amounting to between six and seven thousand. There are several illustrations of dolmens, where, similar to Arthur's Stone, a flat stone rests on several low upright stones: the Kistvaen, or coffin of stone slabs, is a kind of dolmen in miniature. The illustrations of the cromlechs are standing stones either circular, or in alignments, and one instance is given of a square cromlech. The alignments of marshalled stones, the grey granite of the region (Brittany), very rarely showing traces of the chisel, are very remarkable: the stones comprising them are of various sizes, but in one group rising about six yards above the ground, ten to thirteen in a row, they number altogether over two thousand seven hundred.

Our President, Mr. Blashill, had recently visited the locality, and he exhibited some photographs of some of the stupendous masses near Carnac. One photograph represented a prostrate broken stone, most probably a fallen menhir [Map], 78 feet in length, 13 feet at the base, and weighing at least 240 tons.

For the sake of comparison as to size and weight:— Cleopatra's Needle on the Thames Embankment, London, imported from Egypt in 1878 by the late Sir Erasmus Wilson, is 68 feet 52 inches high. Its weight is 186 tons 7 cwt. 2 stones II lbs. One of the largest monoliths in our kingdom is to be seen in the churchyard at Rudstone, a little village in Yorkshire. It is a gritstone over 25 feet high: it has been traced into the ground to a depth of 16 feet without its base being reached. It is computed to weigh 46 tons. It is nearly twenty miles distant from the nearest quarry. An illustration is given in "The Sphere" of September 13th, 1902, on page 294.

The dolmens, no doubt, like the pyramids of Egypt, were constructed for tombs. The Menhirs, or standing stones, may have been monumental, sometimes religious emblems, sometimes memorials of other significance, like the pillar-stones of the Bible.

Weird ancient customs are still maintained amongst the more uneducated of the Bretons even in the present day, customs which the priests endeavour to associate with Christian worship ; very strange popular traditions cling about the megaliths of Brittany.

It is now generally accepted that chambered structures were erected as memorials of some great hero at a period when burial mounds of earth (barrows or tumuli) were wont to be raised over them: some oval or long in form, representing a race existing before the makers of the circular barrows, as inferred from the shape of the skulls found buried under the mounds. Who the Aborigines of our island were remains unsettled. Some believe that the Silures on the western portion were descended from the Iberians of Spain, and the population of the southern and south-eastern parts were derived from the people of the opposite coast of Gaul. A study of the subjects leads to the surmise that some five or six centuries before our era the southern part of Britain was overrun by Celtic ancestors of the Goidels, whose language is represented by the Gaelic dialects of Ireland, the Isle of Man, and Scotland. These were driven northwards in the 2nd or 3rd century B.C. by another branch of the Celtic family, the Brythons, whose conquests are represented by the territory now covering Mid-Wales to the sea.

presented by the territory now covering Mid-Wales to the sea. In the Appendix to the work above referred to, " The Welsh People," on page 640, we read:- "That the pre-Celtic inhabitants of Britain were an off-shoot of the North African race is shown by the cranial and physical similarity between the "long-barrow" man and the Berbers and Egyptians, and by the line of megalithic monuments which stretches from North Africa through Spain and the West of France to Britain, marking the routes of the tribes in their migration."

As a grand memorial of the work of a past race, the origin of which is lost in the mist of pre-historic ages, Arthur's stone still remains a problem for antiquaries ; its mystery and antiquity claim the same respect of visitors, which it possesses of the lord of the manor, Sir George Cornewall, and of the local inhabitants.

We are assured by a resident that the appearance of Arthur's Stone is the same as it has been for sixty years. "The flat superincumbent stone, in three pieces, but the sides of those pieces answering one another," &c., still corresponds with Salmon's description as he saw it about two hundred years ago.