Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2

Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 is in Vetusta Monumenta.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.1 and 2.2 Plans for the Rebuilding of London

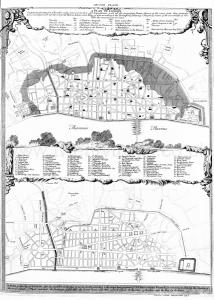

1747. Plates 2.1 and 2.2. Three plans for rebuilding the city of London after the great fire of 1666. The plans were originally submitted to King Charles II in September of 1666 and February of 1668 by John Evelyn and Christopher Wren. Engravings by George Vertue (age 63) after the original plans by Evelyn and Wren.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.3 Portrait of George Holmes

1750. Plates 2.3. Portrait from around 1732 of George Holmes, a founding member of the Society of Antiquaries and Deputy Keeper of the Tower of London. The engraving augments the original oil painting by depicting a more mature Holmes surrounded by objects symbolic of his intellectual and professional pursuits. Engraving by George Vertue (age 66) after Richard van Bleeck.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.4 Deeds and Seals

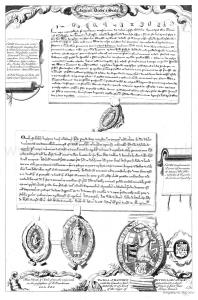

1751. Plates 2.4. Two early to mid-fourteenth-century deeds and three seals, which confirm land charters related to ecclesiastical establishments in Yorkshire. Engraving by George Vertue (age 67).

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.5 A View of the Savoy from the River Thames

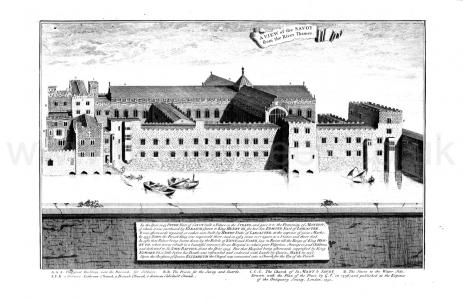

1750. Plate 2.5. Savoy Palace [Map] with C. Saint Mary le Strand, F. Savoy French Church.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.7 Greensted Church

1752. Plate 2.7. Greensted Church with Objects Commemorating St. Edmund. The central image of the Church of St. Andrew, Greensted [Map], Essex, is rendered along with the burial shrine of St. Edmund and a seal fragment from the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds, both in Suffolk. Engraving by George Vertue (age 68) after Smart Lethieullier (age 50) and John Lydgate.

Edmund "The Martyr" King East Anglia: In 855 he was appointed King East Anglia. On 20 Nov 869 he died. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 870. This year the army rode over Mercia into East-Anglia, and there fixed their winter-quarters at Thetford. And in the winter King Edmund fought with them; but the Danes gained the victory, and slew the king; whereupon they overran all that land, and destroyed all the monasteries to which they came. The names of the leaders who slew the king were Hingwar and Hubba. At the same time came they to Medhamsted, burning and breaking, and slaying abbot and monks, and all that they there found. They made such havoc there, that a monastery, which was before full rich, was now reduced to nothing. The same year died Archbishop Ceolnoth; and Ethered, Bishop of Witshire, was chosen Archbishop of Canterbury.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.8 Gloucester Cross

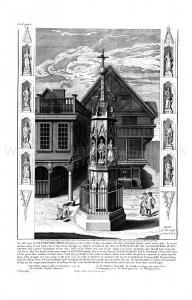

1751. Plate 2.8. Gloucester Cross [Map], framed by scaled-up images of the sculptures of English kings and queens that were located in the niches of the second story. Engraving by George Vertue (age 67) after Thomas Ricketts.

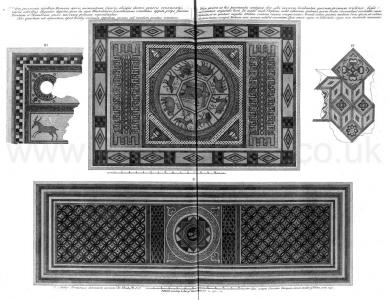

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.9 Mosiacs found at Winterbourne and Roxby

1752. Plate 2.9. Three fourth-century CE Roman mosaic pavements discovered in North Lincolnshire in 1699 and 1747. Figures I-III depict two large nearly intact pavements, the Ceres and Orpheus Pavements, with a related fragment, all discovered at Winterton in 1747. Figure IV shows a fragment of a large geometric mosaic discovered nearby at Roxby in 1699. Engraving by George Vertue (age 68) after Charles Mitley.

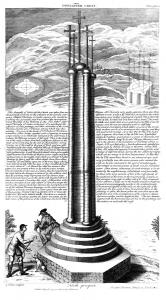

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.10 Doncaster Cross

1752. Plate 2.10. Doncaster Cross [Map], also known as the Hall Cross, which was erected at the southeastern end of Doncaster, near Hallgate, on the old London road, in honor of Otho de Tilly, land steward to the count of nearby Conisborough from about 1165 to 1188. The dense text on either side of the cross relates a brief history of Otho de Tilly. Engraving by George Vertue (age 68). The original cross in Doncaster, UK, was demolished in 1792 but was replaced by a replica ex-situ the following year.

Originating from the village of Tilly in Calvados (Normandy), Otho de Tilly (c. 1121-88) first appears in the historical record during the reign of Stephen of Blois (d. 1154), for instance, as witness to the charter of foundation of Kirkstall Abbey in 1152. He subsequently served as senescallus comitis de Conibroc (seneschal or land steward to the count of Conisborough), Hamelin de Warenne (1129-1202), the illegitimate half-brother of Henry II, who first came into possession of Conisborough Castle in 1163 and extensively rebuilt it – with the addition of a new polygonal stone keep – between 1180 and 1190. Given that Conisborough is located just under six miles down the road from Doncaster, it is likely that the cross that bore Otho's name was erected sometime during his tenure as seneschal to the Warennes—probably between the mid-1160s and Otho's death in 1188.

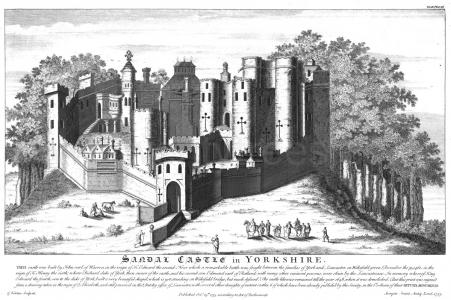

Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.11 Sandal Castle

1753. Plate 2.11. Sandal Castle [Map]. Engraving by George Vertue (age 69) after a drawing originally produced for a survey of the properties of the Duchy of Lancaster conducted by the Chancellor of the Duchy, Ambrose Cave, in 1561.

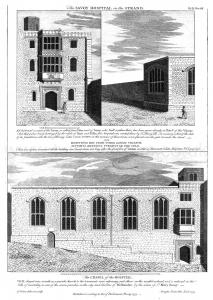

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.12 Savoy Hospital

1753. Plate 2.12. The prison and chapel buildings in the Savoy Hospital in 1736. The Hospital Chapel, depicted from two different sides in the lower half and the upper right portion of this plate, is the only Savoy building that survives today. Engraving by George Vertue (age 69) after his own drawings.

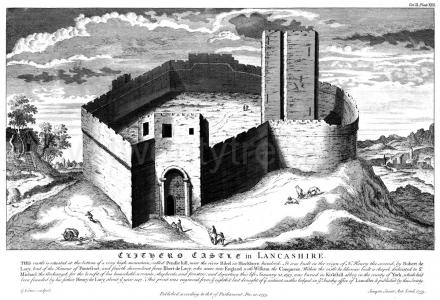

Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.13 Clitheroe Castle

1753. Plate 2.13. Clitheroe Castle [Map]. Engraving by George Vertue (age 69) after a drawing originally produced for a survey of the properties of the Duchy of Lancaster conducted by the Chancellor of the Duchy, Ambrose Cave, in 1561.

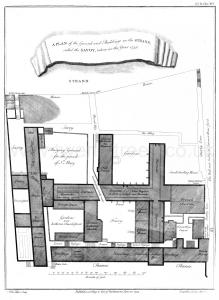

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.14 Plan of the Savoy

1753. Plate 2.14. Plan of the Savoy Palace [Map]. Engraving by George Vertue (age 69) after his own drawings.

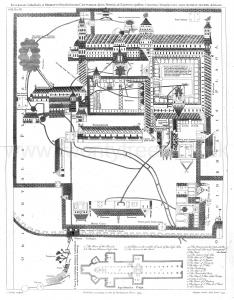

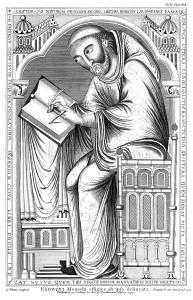

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.15 and 2.16 Eadwine Salter

1755. Plate 2.15 and 2.16. Two images from a twelfth-century manuscript, the Eadwine Psalter. The first is a plan of the monastery precinct at Christ Church, Canterbury, including Canterbury Cathedral [Map] as it stood prior to 1174. The second plate reproduces an author portrait of Eadwine of Canterbury, after whom the entire manuscript is named. Engravings by George Vertue (age 71) after drawings of the manuscript made at Cambridge in 1753 by an unknown draftsman.

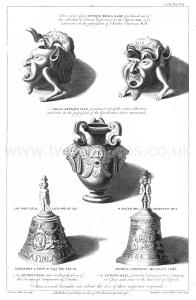

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.17 Roman Lamp

1756. Plate 2.17. A Roman lamp, an amphora-style vase, and two hand bells from 1366 (left) and 1547 (right). Engraving by George Vertue (age 72) (his last for Vetusta Monumenta) after his own drawings.

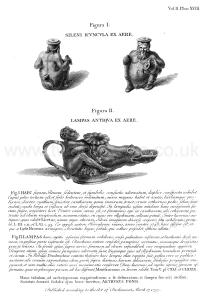

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.18 Two Roman Bronzes

1757. Plate 2. Two small Roman bronze lamps, one in the form of Silenus and one composed of a Bacchanalian figure astride an ass's head. Engraving by Arthur Pond (age 52) after his own drawings and those of Richard Cosway.

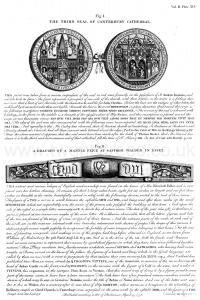

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.19 Seal of Canterbury Cathedral

1758. Plate 2.19. Third conventual seal of Canterbury Cathedral (13th century) and a segment of a wooden mantelpiece from a house in Saffron Walden featuring carved images and letters (16th century). Engraving by James Green after drawings provided by John Ward.

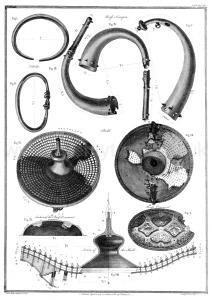

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.20 Bronze Age Horns and Medieval Brooch

1763. Plate 2.20. Two silver arm rings and three bronze horns from Ireland, a fifteenth-century buckler from Wales, and a Viking Age brooch from the Western Isles of Scotland. Engraving by James Basire Sr. (age 33) after his own drawings.

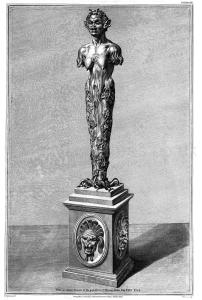

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.21 and 2.22 Bronze Statuette

1765. Plate 2.21. Bronze statuette, 22 1/4 inches high, believed in the eighteenth century to be of ancient origin. It was acquired by Thomas Hollis (age 44) in Italy in 1753 and exhibited at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1758, after which Hollis donated the drawings here reproduced. Engravings by James Basire Sr. (age 35) after drawings by Giovanni Battista Cipriani.

Thomas Hollis: On 14 Apr 1720 he was born. In 1757 Thomas Hollis was elected Fellow of the Royal Society. On 01 Jan 1774 he died.

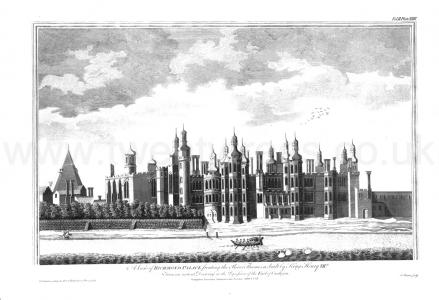

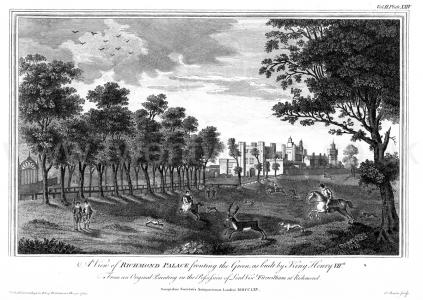

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.23 Richmond Palace

1753. Plate 2.23. Richmond Palace [Map]. Engraved by James Basire Sr. (age 23).

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.24 Nonsuch Palace

1765. Plate 2.24. Nonsuch Palace [Map]. Engraved by James Basire Sr. (age 35).

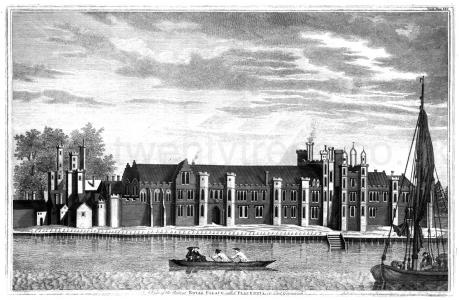

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.25 Palace of Placentia

1753. Plate 2.25. Palace of Placentia, Greenwich [Map]. Engraving by James Basire (age 23) after George Vertue (age 69).

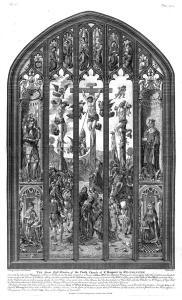

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.26 East Window of St Margaret's Church

1765. Plate 2.26. East Window of St Margaret's Church, Westminster [Map]. A sixteenth-century Flemish-inspired stained-glass window produced in Holland and shipped to England around 1526. Known now as the "Great East Window at St Margaret's Church, Westminster," its three central lights show the Crucifixion, and its two outer lights feature portraits of King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. The window was first installed in the Church of Waltham Abbey, and then moved to New Hall, Essex during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The window was installed in St. Margaret's in 1758. Engraving by James Basire (age 35) after George Vertue.

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.27 Hampton Court Palace

1769. Plate 2.27. Hampton Court Palace, Richmond [Map]. Etching by John Pye after an anonymous drawing copied by Michael Tyson.

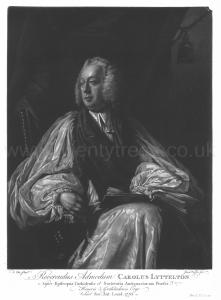

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.28 Charles Lyttelton

1765. Plate 2.28. Engraving of a portrait of Bishop Charles Lyttelton (age 51) from around 1765, Bishop of Carlisle and President of the Society of Antiquaries of London from 1765 to 1768. This portrait was likely painted to commemorate his appointment as president of the Society in 1765. Engraving by James Watson after Francis Cotes.

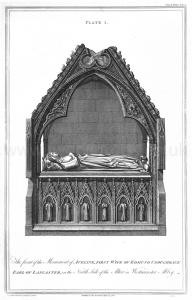

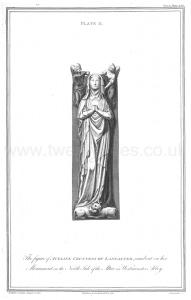

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.29 to 2.31 Effigy of Aveline Countess of Lancaster

1780. Plates 2.29, 2.30 and 2.31. Effigy of Aveline Forz 6th Countess Albemarle and Lancaster. Engravings by James Basire, Sr. (age 50) after his own drawings, or possibly those of his apprentice, William Blake.

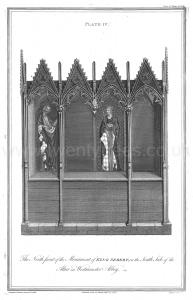

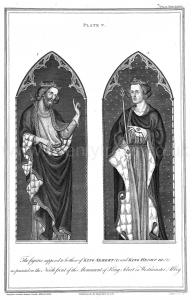

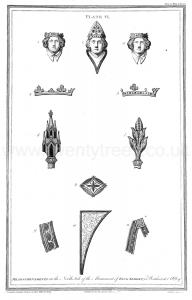

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.32 to 2.34 Monument of King Sebert

1780. Plate 2.32 to 2.34. Monument of King Sæberht of Essex in Westminster Abbey [Map].

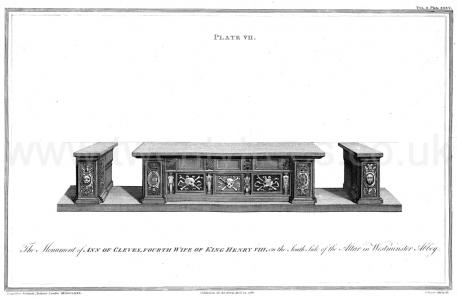

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.35 Monument to Anne of Cleves

1780. Plate 2.35. Monument to Anne of Cleves Queen Consort England at Westminster Abbey [Map].

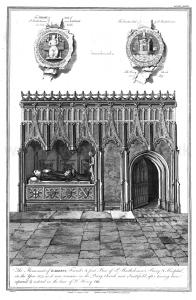

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.36 and 2.37 Monument to Rahere

1784. Plates 2.36 and 2.37. Monument to Rahere at St Bartholomew's Hospital.

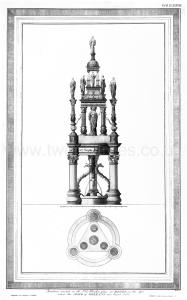

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plate 2.38 Fountain at Rouen

1780. Plate 2.38. Fountain dedicated to the memory of Joan of Arc in Rouen, France [Map], Normandy. The fountain was erected in 1525 at what was believed to be the site of Joan's execution in 1431. Engraving by James Basire Sr. (age 50) after a drawing made in France, possibly by Louis-Jean Allais, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Descamps.

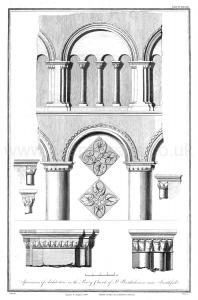

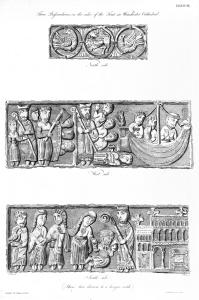

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.39 and 2.40 Winchester Cathedral Font

1786. Plates 2.39 and 2.40. Twelfth-century baptismal font in Winchester Cathedral [Map]. Carved of a blue-black limestone commonly known as "Tournai marble," the north and east sides of this font depict eight birds and a mammal, and the south and west sides present hagiographical scenes from the life of St. Nicholas of Myra (also known as "Saint Nick" or Santa Claus). Engravings by James Basire Sr. (age 56) after John Carter.

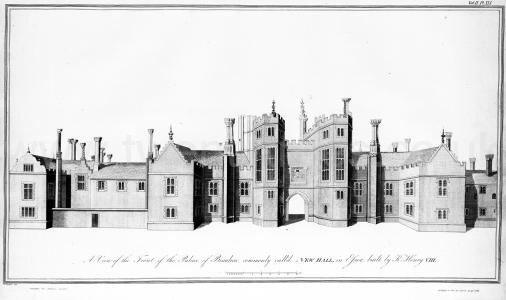

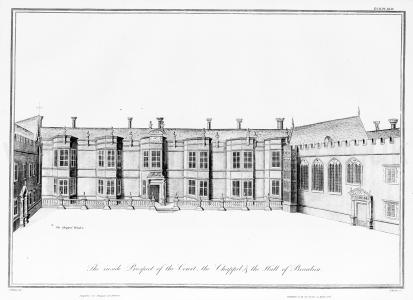

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.41 and 2.42 New Hall

1786. VOL. II. NEW HALL in Essex. THE splendid taste in architecture, a composition of Roman and Gothic introduced by Italian artists, which first made its appearance among us in the reign of Henry VIII. discovered itself in the number and variety of palaces erected by that magnificent monarch. There was hardly an agreeable situation within 30 miles round his capital which he did not convert into a palace for himself, or a nursery for his children. On Hunsdon-House, in Hertfordshire, £.19,000 were expended by him in the space of three years1.

Note 1. Walpole's Anecd. of Paint. I. 125.

The mansion-house, called the NEW HALL, in Boreham parish, in Essex, was purchased by him in the ninth year of his reign, 1517, of Richard Fitz James, bishop of London, by virtue of the will of Thomas Boteler, earl of Ormond2; or, as others say, by exchange with Thomas Bullen, earl of Wiltshire.

This noble lordship was antiently part of the possessions of the monastery of Waltham. About 24 Edward II. the abbot and convent granted it to Sir John of Shardelow, knight, Joanna his wife, and Thomas his brother, with their manors of Campes and Orseye, c. Cambridge, in exchange for the manors of Copped-Hall and Shingled-Hall, in Epping3. But in the 47th of the same King, Sir Thomas de Shardelow granted this manor of New Hall, with its appurtenances in Boreham, Springfield, Little Badow, Little Waltham, Bromfield, and Hatfield Peverel, unto Sir Henry de Coggeshall, knight, in free and perpetual exchange for the manor of Bradeker, in Shropham and Holkham, c. Norfolk4. This Sir Henry de Coggeshall was of an antient family so named from the town of Coggeshall5, where they had considerable estates. He died about 49 Edward III. leaving Sir William, his son and heir, in whom the direct male line of the family failed; and a vast estate was, by his four daughters and coheirs, transferred into other houses. This estate was however settled on his brother Thomas, who had the lordship of Sandon, where he probably resided. He held the manor of New Hall, 15 Richard II. and died 10 Henry V.6 leaving Richard, his son and heir, 13 years old.

But at this time New Hall was holden by John de Boreham, and others; though on what account is not specified. And 6 Henry VI. Robert Darcy, of Malden, ancestor of the Barons Darcy Of Chiche, granted to Sir William Hungerford, &c. two parts of the manor called in New Hall, in Boreham7.

Note 2. Inq. 9 H. VIII.

Note 3. Writ ad quod damnum [Writ to what damage], 24 E. II.

Note 4. Cart. 47 Ed. III.

Note 5. In Boreham church several of the Coggeshalls were buried. See an account of their tombs, effigiess in windows, &c. in Symons's Essex Collection, in Coll. Armor.

Note 6. Inq. 10 H. V.

Note 7. Claus. 6 H. VI.

Richard de Coggeshall above mentioned died 11 Henry VI. leaving Elizabeth his sister and heir. This manor was still in the hands of John De Boreham and others2.

Next we find it in Richard Alred, who may have married the said Elizabeth. He died 26 Henry VI. seised of the manor of New Hall, holden of Margaret, Queen of England, as of her manor of Great Badow, parcel of the Duchy of Lancaster; and 40 acres of arable land, in Boreham, lying near Cobbiswode, holden of John earl of Oxford; and one messuage, 100 acres of arable, 20 acres of meadow, 12 acres of pasture, and 6 of wood, lying in Springfield, Little Waltham, Great Leyes, Terling, Boreham, and Bromfield, called Nobatt, which was formerly the estate of Robert Nobatt and others; of Sir John Bourchier and Thomas Tyrel, knights, leaving William, his son and heir, 15 years old, to whom, by his will, dated March 8, 1446, he bequeathed particularly the manor of New Hall, with its appurtenances3.

Afterwards this estate fell to the crown; whether by forfeiture, during the wars between the houses of York and Lancaster, or otherwise, Mr. Morant could not determine. Perhaps, the manor of Great Badow being part of the Duchy of Lancaster, this might have fallen into it by escheat, exchange, or purchase.

We find it next in the noble family of Boteler, earl of Ormond, who had zealously adhered to the house of Lancaster. James Boteler, who was created earl of Wiltshire, 27 Henry VI. and became earl of Ormond on his father's death, 1451, was with Henry VI. at the battle of St. Alban's; and, on his behalf, also, at the battles of Wakefield, Mortimer's-cross, and Towton, at which last, being taken prisoner, he was beheaded, 1460, and attainted 1461, I Edward IV. John, his next brother, was also attainted 14 Edward IV.4 But Thomas, the third brother, living to see Henry VII. on the throne, that prince gave him the manor of New Hall, in recompense for the sufferings of his family; and in the 7th of his reign granted him licence to build there walls and towers5. He left only two daughters, whereof Margaret, the eldest, was married to Sir William Bullen, of Blickling, c. Norfolk. knight, who had by her Sir Thomas Bullen, his son and heir, advanced 18 June, 1525, to the title of viscount Rochford, soon after made knight of the Garter; and, 24 January, 1529, created earl of Wiltshire and Ormond; and the 24th of January following constituted Lord Privy Seal. All these honors were conferred on him out of the great regard Henry VIII. had for his daughter, the lady Anne, whom he soon after married.

In this king's reign one Mr. Colt lived at New Hall whose eldest daughter, Sir Thomas More married. He was John Colt of Nether-Hall, in Royden6

The king purchased this manor in the 9th year of his reign, 1517, of Richard Fitz James, bishop of London, by virtue of the will of Thomas earl of Ormond. Camden7 says that he procured it of Thomas Bullen, earl of Wiltshire, by exchange. So pleased was he with the situation, that he gave it the name of BEAU LIEU, which name, however, never came into general acceptation8 He also erected it unto an HONOUR, and greatly adorned and improved it. Here he kept the feast of St. George. 15249

Leland dates the improvements made in several of the royal houses to the leisure which Henry enjoyed by the peace of Cambray between the Emperor and the King of France, on which occasion he had behaved so generously to the latter by giving him up the Emperor's bonds to restore his two sons, who were left as hostages, returning the jewels which France had pawned to him, and forgiving him all the expences he had been at to assist him, by a mutual discharge on both sides10.

Note 2. Inq. 11. H. VI.

Note 3. Inq. 26 H. VI.

Note 4. Dugd. Bar. II. 235.

Note 5. Pat. 7 H. VII.

Note 6. Morant, Essex. I. 490.

Note 7. Britannia, Essex.

Note 8. Camden ubi sup.

Note 9. Grafton's Chron. p. 553.

Note 10. Rapin VII. 310, 407.

See Note 11 below for translation.

Anglus tam placidae quietis autor

Gaudet munere pacis innovato:

Quoscunque artifices favens politos,

Hac lege ut laceros palatiorum

Muros restituant labore justo,

Conferantque suum novis nitorem.

Hinc crevit Viridis sinus2 corona;

Hundesdenaque pervenusta sedes;

Hinc BELLUS LOCUS extulit serenae

Frontis lumina, Brigidae et sacer Fons3

Aedes magnifico decore festae.

Hinc Thornega4 vetus suos honores

Auxit splendida principum cathedra:

Shelfesega5 etiam domus renidens

Signis ventivolis et albicante

Crista. Sideris instar est Avona6

Ottelandaque7 verticem alta tollit.

Et Nulli titulo8 domus secunda

Caelo quae caput inserit corusco9

Note 2. Greenwich.

Note 3. Bridewell.

Note 4. Westminster.

Note 5. Chelsea.

Note 6. Hampton Court.

Note 7. Oatlands.

Note 8. Nonsuch.

Note 9. Cygnea Cantio.

Note 10. Translation: The English author of calm repose takes joy in his gift of renewed peace, showing all skilled artisans his favor on this condition: that they rebuild the dilapidated walls of his palaces with just labor and confer a splendor of their own making to new ones. Herefrom has grown the crown of Viridis sinus (Greenwich), and the very charming seat of Hundesdena (Hunsden); herefrom Bellus Locus (Beaulieu) has lifted up the lights of its serene brow, as has hallowed Brigidae Fons (Bridewell), a festive residence of magnificent beauty. Herefrom venerable (Thornega) Westminster, illustrious seat of rulers, has added to its honors. Shelfesega (Chelsea) too, a home resplendent with banners blowing in the wind and its white crest. Like a star is Avona (Hampton Court), and Ottelanda (Oatlands) lifts its head aloft. And his home, second to none in name (Nonsuch), which inserts its head into the gleaming firmament.

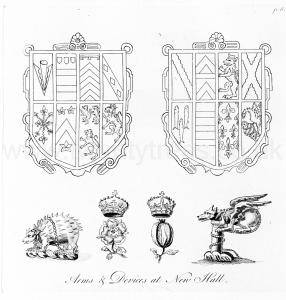

Mr. Morant thinks it most probable that the old house here was either new built or repaired by Thomas, earl of Ormond. But it was greatly adorned and improved by Henry VIII. who built, in particular, the noble gate-house leading into the grand court, as appeared by his arms10 over the gate, carved in stone, supported by a lion and griffin, with this inscription under them: henricus rex octavus, rex inclitus armis, Magnanimus struxit hoc opus eximium11 [King Henry VIII, a king renowned in arms, nobly erected this outstanding work.]

They are said to have been brought from the gateway in one of the courts erected by this king, and are now over a door opposite the grand entrance, which door formerly lead into a spacious court12.

Note 10. Quarterly, France and England, supported by a greyhound and griffin. A rose and pomegranate intertwined at bottom, and singly crowned over the head of each animal.

Note 11. Symons gives it egregiū.

Note 12. Of these two the Society have drawings, by Mr. Vertue.

His daughter Mary, afterwards Queen of England, resided here some time13.

It received further improvement from Queen Elizabeth, who probably made it one of her retreats.

Over the house door were the arms of England as before, in a garter, supported by a crowned lion and a griffin sided by cariatides; over them this inscription.

VIVA ELIZABETHA. [Long live Elizabeth.]

Under the arms,

IN TERRA LA PIU SAVIA REGINA, EN CIELO LA PIU LUCENTA STELLA. VIRGINE MAGNANIMA, DOTTA, DIVINA, LEGIADRA, HONESTA, E BELLA. [On earth the wisest Queen, in Heaven the brightest star / Noble, learned, divine, graceful, honourable, and fair virgin.]

Note 13. Fox's Book of Martyrs.

May 28, 1573, Queen Elizabeth granted to Thomas Ratcliffe earl of Suffolk, all that capital mansion-house commonly called the Honor and Manor of Biewliew, alias Newhall, or Biewliew-house, and all the buildings and demesne lands thereto belonging, with the Old Park1 And Dec. 31, following, she further granted to the same earl all the manor of Boreham, the manor of Walkfare, the manor of Oldhall, and the honour of Beauliew, alias Newhall2 This nobleman was lord deputy and lieutenant of Ireland, in the reign of her predecessor, and was continued in that office by herself; he was also lord president of the North in her twelfth year, and made several successful inroads into Scotland. He was employed in several foreign negotiations, and sat as one of the peers on the duke of Norfolk's trial, and was lord chamberlain of the household at the time of his decease, June 9, 15833. By a deed of feofment, dated Dec. 20, 1579, he settled the manor of Beaulieu, alias Newhall, with divers other lordships and lands in Essex and elsewhere, on the issue male of his own body until the tenth son: remainder to his brother Sir Henry Ratcliffe, knight, for life, and, after his decease on Robert Ratcliffe son and heir apparent to the said Henry and the heirs male of his body, and for a lack of such issue on Thomas Ratcliffe, esq. son and heir of Sir Humphrey Ratcliffe of Elnestow, c. Bedford, knight, deceased, and the heirs male of his body; remainder to Edward Ratcliffe second son of the said Sir Humphrey, and the heirs male of his body; and for default of such issue to the lady Frances his sister, then wife of Sir Thomas Mildmay, knight, and the heirs of his body by her4 He married first Elizabeth daughter of Thomas Wriothesley earl of Southampton, by whom he had two sons who died young; and secondly, Frances daughter of Sir William Sydney, knight, sister of Sir Henry Sydney Knight of the Garter, but dying without issue male surviving, he was succeeded in this and his other estates by his brother Henry earl of Sussex, who died April 10, 15945, leaving his only son and heir Robert, who, though, as his grandfather, he married two wives, yet died without issue male surviving, Sept. 22, 16296. Before his decease he had sold this estate for £30,000. to George Villiers duke of Buckingham, on whose murder by Felton, Aug. 23, 1628, it descended to his son George, a minor, duke of Buckingham, who having, 1648, engaged with the earl of Holland and others to rise in behalf of king Charles I. and being defeated and dispersed at Kingston upon Thames, the parliament voted him a traitor, and sequestered his estates. This was sold by the commissioners appointed by parliament for that purpose7 and purchased by Oliver Cromwell; the consideration money being 5s. and the computed yearly value £.1309. 12s. 3½d.8 But in 1653 he exchanged it for Hampton Court, paying the difference9 It was then sold to three wealthy citizens of London for £.18,000. Mr. Morant says, "Undoubtedly the duke of Buckingham recovered it at the Restoration." Whether he did or not, it was then purchased by George Monk duke of Albemarle, who lived here in a splendor which greatly reduced his fortune, and dying Jan. 4, 1669-70, was succeeded in his estate and title by his only son Christopher, who died 1688, in Jamaica, of which he had been appointed Governor the year before. He married Elizabeth eldest daughter of Henry earl of Ogle, son and heir apparent to William Cavendish duke of Newcastle, who being jointured in this estate was remarried 1691 to Ralph Duke of Montague. From that time this noble mansion was neglected and became ruinous. Her Grace died at Newcastle House, near Clerkenwell-church, Aug. 28, 1734, in the 96th year of her age.

Note 1. Pat. 16 Eliz.

Note 2. Pat. 17 Eliz.

Note 3. Dugd. Bar. II. 286.

Note 4. Ib.

Note 5. Ib. 287.

Note 6. Ib. 288, [sic]

Note 7. Scobell's Collection of Acts July, 1651. c. 10.

Note 8. Mr. Booth's MS. Collections for Essex.

Note 9. Parliamentary History, XX. p. 223.

But before her decease Benjamin Hoare, esq. youngest son of Sir Richard Hoare, banker in Fleetstreet, and Lord Mayor of London, 1713, had bought of her heirs the reversion of New Hall, and other estates appendant thereto. With the marble and other materials of this mansion he decorated the house which he built on the opposite or South side of the London road to Harwich. He died Jan. 12, 1749, leaving issue Richard. But before his death he sold New Hall, in 1737, with the gardens, park behind it, and the fine avenue (but none of the land on each side of it) to John Olmius, esq. who after tak[ing] down the more extensive appendages of this royal seat, fitted up the remaining part, including the great hall, above 40 feet high, 90 long, and 50 wide, for a residence for himself and successors, which his son has considerably improved. He married, 1741, Anne daughter and heiress of Sir William Billers, knight, Lord Mayor of London; was created, 1762, baron Waltham of Philipstown, in the kingdom of Ireland, and dying March 12, 1764, was succeeded by his eldest son Drigue-Billers Olmius, the second baron and present proprietor of this mansion, 1786.

Like Audley End, New Hall has been reduced from two courts to the central part, or the South side of the inner court, consisting of the great hall and apartments connected with it.

Over the door leading to the chapel are, or were, these arms and quarterings carved in stone of Thomas Ratcliffe earl of Sussex, with those of his lady Frances Sydney, daughter of Sir William Sydney of Penshurst in Kent, knt. the celebrated founderess of Sydney Sussex College, Cambridge, and whose time by these arms we may conclude some additions were made to this mansion:

1. A bend ingrailed. Ratcliffe earl of Sussex.

2. A fess between two chevrons.  Fitzwalter Arms.

Fitzwalter Arms.

3. A lion rampant crowned, within a bordure. Burnell.

4. A saltire ingrailed. Botetourt.

5. Three lucies hauriant.  Lucy Arms.

Lucy Arms.

6. Three bars.  Multon Arms.

Multon Arms.

7. Semee Fleurs de lis. Mortimer of Attilborough.

8. An eagle and child. Culcheth.

Over the door leading to the hall those of Frances countess of Sussex, his consort:

1. A pheon. Sydney.

2. Two bars, in chief three shields. Clunford.

3. Three chevronells; a label of 3 points. Barrington.

4. On a bend three lozenges or muscles. Mercy.

5. Quarterly an escarbuncle.  Mandeville Arms.

Mandeville Arms.

6. A chevron between three mullets. Chetwynd.

7. Three lions rampant. Baard.

8. Barry of 8 a lion rampant crowned.  Brandon Arms.

Brandon Arms.

A bear chained: the crest of Dudley earl of Leicester.

A griffin chained.

A rose crowned. Henry VIII.

A pomegranate crowned. Catharine of Arragon, his queen.

These coats and devices are here engraved from drawings taken by Mr. Vertue at the same time that he made those of the house.

The beautiful painted window now in the church of Saint Margaret at Westminster once contributed to the decoration of this palace. It was intended as a present to Henry VII. for his chapel at Westminster, from the magistrates of Dort in Holland; but he dying before that building was completed, it was set up in the abbey church of Waltham, and remained there till the dissolution, when it was removed to the chapel at New Hall, where it was preserved with great care for near two centuries. Mr. Olmius sold it for £50. to the late John Conyers, esq. of Copthall, who at that time had thoughts of placing it in the chapel of that venerable mansion of the abbots of Waltham. But soon after altering his intention of keeping that house in repair, and preferring the more expensive plan of building a new one on a higher situation, the window remained in the packing case till the parishioners of St. Margaret purchased it of him for four hundred guineas, in 1758. The print engraved by Mr. Basire, 1768, from drawings taken by Mr. Vertue, at the same time that he made those of the house and its ornaments, renders it unnecessary to enlarge on the subjects represented in this window, which are the crucifixion, accompanied by portraits of Henry VII. and his queen1, taken from original pictures, sent to Dort for that purpose. Over the king is the figure of St. George, and above him a white rose within a red one: over the queen stands St. Catherine, and in a panel above her is a pomegranate Vert in a field Or. the arms of the kingdom of Grenada2. The objections raised at the time against fixing up this window in the church of St. Margaret, and the admirable defence of the whole proceeding made by one of the residentiaries of the adjoining collegiate church, founded on arguments drawn from historical practice, supported by a suitable taste for the polite arts, as well as for the monuments of antiquity, are too well known to require a detail in this place.

Note 1. Of these portraits the Society have sketches of the original size by Mr. Vertue.

Note 2. From the badge over the queen some have supposed the portraits intended for prince Arthur and the princess Catharine of Arragon: but against this the royal crowns and mantles seem strongly to militate.

In Symons's Essex collections in the Heralds Office is a rough plan of some painting at New Hall done for the duke of Buckingham, with his arms and those of his lady, Catharine Manners, and his motto Fidei Coticula Crux [The Cross, Touchstone of Faith]. What the painting was, is not said, but it seems to have been in the chapel. Inigo Jones designed it, and Jarbier (Sir Balthasar Gerbier) painted it, for which he had £.500.—He also says the removing the duke's household there cost £.500, and that in his (Symons') time the rental was £.1100 per. ann.

The venerable avenue to this palace from the London road still remains the pride and boast of the neighbourhood. It is near a mile long, and has double rows of trees on each side. A number of fine furs, some of them coaeval with the royalty of the place, planted on each side of this avenue, were felled and sold about twenty-five years ago.

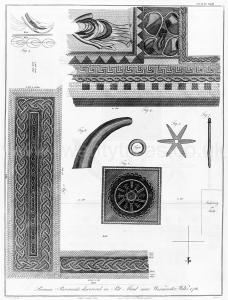

Culture, England, Societies, Society of Antiquaries of London Publications, Vetusta Monumenta Volume 2 Plates 2.43 Roman Pavements Found Near Warminster

1786. The tesselated pavements exhibited in this plate were discovered, in March and November, 1786, in a common meadow, called Pitt-Mead, near Warminster, in the county of Wilts. Through the particular attention of a lady then in the neighbourhood, sketches of them were made before the greater part of them were destroyed by the ignorant peasantry. Her account of them, and of further discoveries which she procured to be made, were communicated in a letter to the Hon. Daines Barrington, which is here subjoined, as it was read before the Society of Antiquaries, Jan. 21, 1787.

Warminster, Jan. 6, 1787.

"Sir

"Pitt Meadow (or Mead, as it is more generally called), a common pasture field, is situated about a mile and three quarters east of Warminster (supposed Verlucio), between the two villages of Bishopsrow and Norton-Bavant, and about six hundred yards south of the turnpike road leading to Sarum. Through one side of it runs the river Wily; it is the property of divers persons, therefore divided by small trenches or gutters leading to the river. On one of these divisions, about an acre and a half, the property of a nobleman in the neighbourhood [Lord Weymouth], the tenant, in March 1786, being about to make the surface somewhat more level, discovered ruins[.] This induced him to go lower than he intended, and he presently came to the tesselated pavement which I have delineated No 1. The fame of this reaching Warminster, an ingenious person of this place took a sketch of the figure and colours; but, as the country people soon demolished and carried away the whole of it, and as nobody seemed to stir in the matter, he threw it by, and no more was thought of Pitt-Mead, till a Mr. Walker, lecturer in philosophy, came to the town, who was accidentally informed of what had been found, in consequence of which he visited the spot, saw some loose tesselae, broken tiles, &c. and inserted a paragraph in the Salisbury Journal, though very unsatisfactory. Seeing this (for, being a stranger in the place, I had heard nothing of it before), on the 16th of November, after applying to the occupier for permission, I took a man over, and began to dig, when to my great satisfaction, about two feet below the surface I hit upon the top of the pavement No 2, and traced it to its full extent. Continuing the search, on the eighteenth was discovered, by the Rev. Mr. Massey, at the head of the last-mentioned floor, but not more than half a foot below the surface, an imperfect floor, No 3, but so decayed that I could make little or nothing of it, nor could we at that time find a continuation of it; for which reason, added to the severity of the weather, we desisted from any farther investigation at that time. But the above-mentioned Nobleman, hearing of our discoveries, employed some men there, who in the course of a few days, Nov. 22, came to the beautiful remains No 4. This was likewise not more than half a foot below the surface, and in some places not more than four inches, which I suppose to be at the cause of so large a part of it being destroyed. The men still continued to open different parts, and on the west side of No 1 came to what I take to be a bath, or sudatory; the floor, a very hard cement, composed of something extremely white, like marble, broken in pieces, sand, brick, oyster-shells, broken together, what about three feet below the surface. Upon breaking up a point of it, I found some pieces of burnt wood, in a kind of drain or flew. The men then proceded lower in the mead (that is, nearer to the water), and at about eight feet from the pavements, No 1 and 2, discovered the foundation of a wall, two feet thick, running in a direct line, east and west, turned up, and continued by the outside of the pavement No 2, at about the distance of four feet from it. This is the last discovery; but one man is still at work, and as they politely gave me leave to direct his search, on Monday last I set him to open the uninvestigated part between No 1 and the above-mentioned wall, looking upon that as the most likely spot to find somewhat to gratify the curious: however he has as yet discovered nothing material, except you may think an iron star (which I look upon to be the rowel of a spur), a ring of the same metal, and, nearer the wall, an ivory bodkin or pin, together with part of a horn; the figures and sizes of all which I have faithfully given at No 5, 6, 7, 8. Though I have not the least doubt but there are many places yet untouched that would afford ample entertainment to the curious antiquary, were there a person well versed in these matters to superintend the search; at present, for want of skill and management, all is random work and confusion. In all our researches, nothing else has been found that is perfect; but great variety of worked tiles and broken pieces of pottery, of all colours, kinds, and shapes. I have the foot, and a small part of the body, of an urn, of beautiful black pottery, much resembling Mr. Wedgwood's tea-pots, and several bits of glass, very different to what is now made, or any I have ever seen, a great variety of bones, human and animal, one skull of astonishing thickness and magnitude, and four teeth in the lower jaw extremely sound and even.

I must now, though with infinite regret, make known the fate of these valuable remains of antiquity. The pavement No 1, I observed above, was immediately torn to pieces. No 2 was, about a week after it was discovered, almost totally destroyed by a clown, who took up the greatest part of it, and carried it away by night. No 3 was demolished in like manner. But, I have the pleasure and satisfaction to inform you, the elegant part of No 4 is preserved by the ingenuity of my Lord Weymouth's surveyor, and carried to his Lordship's seat at Longleat, where it will be safe from the depredations of the vulgar. The method he made use of was as follows: after providing a sufficient quantity of canvas, he made a cement of wax, resin, and tallow, melted upon the spot, and, after picking and cleaning the joints of the tesselae very well, spreading the cement upon a piece of canvas equal to the size of the piece of pavement he intended to take up at one time (which in general was about three quarters of a yard square), laid it upon the face of the tesselae, upon that two or three sheets of strong brown paper and a flat board, then undermined the piece with large iron pins, and, when the cement was cold, turned it up, put it into hampers, and carried it away. When at home, he laid a thick coat of plaster of Paris on the bottom part of the tessela, the heat of which caused the cement to fall from the face side, and leave the figures entirely clean and perfect. I have been thus particular in the process he observed, in hopes the hint may be the means of preserving future discoveries of this kind.

I have nothing to add relative to this particular spot, save that there is evidently a raised causeway leading from it across the meadows to Bishopsrow; and that the learned and honourable Society may depend upon the accuracy of the draughts, as I took them all (except the first, which I copied from the before-mentioned sketch) upon the spot, which no other person had the opportunity of doing. As to the execution, conscious as I am of a great deficiency, having never had the least instructions, I can with truth say, nothing but an ardent desire of preventing what most people think so important a discovery from being hid from your learned body, could have induced me to let it meet the eye of taste and science. At the other end of the mead (which is about a quarter of a mile in length) stand two tumuli or barrows. I got permission to open one of them, had a cut made about two feet and a half wide, quite across it, and in the middle, about four feet from the top surface, found an unbaked urn full of burnt bones and ashes, but to my great mortification nothing else. Near to these barrows I also yesterday discovered evident ruins of an oblong form: I made a man dig a small hole, and I met with many worked tiles, Roman bricks, &c. &c. Upon informing Lord Weymouth's steward of it, he promised to have it properly investigated, when, if any thing is discovered of consequence, I will do myself the honour of again addressing you. In the mean time, permit me to say, if these indigested hints are capable of affording the least satisfactory information to the honourable Society, I shall be abundantly recompensed for the trouble of committing to paper; and have the honour to subscribe myself, with all imaginable respect, Sir, your most obedient, and very humble servant,

CATH. DOWNES.

P.S. I am possessed of a small collection of coins, and amongst them one of fine brass, inscribed, "DIVVS ANTONINVS:" the reverse, a kind of standard, without any legend1.

Note 1. By the account of this discovery communicated to the Editors of the Gentleman's Magazine, 1787, printed in vol. LVII. p. 22, withs a sketch of the pavements, urns, stylus, &c. it appears that a coin of Claudius Gothicus was found sticking to the foot of an earthen vase.

In a second letter, of Feb. 2, 1787, Mrs. Downes says "Some men, employed to fill up the space where the long tesselated pavement (No 2) was taken from, on the 24th of last month discovered another border, running from the lower (or Northern) end of that, in a line due West, between the pavement No 1 and the wall, mentioned in my first letter. About ten feet of it in links is entirely perfect, as was also the joining with No 2; but the Western extremity is so much decayed or damaged, that it is impossible to trace the termination. The colours and figure are exactly the same as a part of No 2; but that you may the more readily comprehend my meaning, I have taken the liberty of scratching the figure and situation upon the blank side of this letter2. This last piece is carefully covered over with turf and mould, so as to preserve it from the injuries of the weather; and all further search is deferred till March, when, I am informed, Lord Weymouth intends to make a thorough investigation of the whole spot."

Thus far in regard to the discovery.

Note 2. In the plate it is put in its proper place.

Mr. Horsley observed, Wiltshire abounds with Roman antiquities; Roman coins, and tesselated pavements, &c. have been found at several places, which argue that the Romans must have had some settlements here, and some military way passing through the county. Dr. Stukeley3 has traced out that along which the xivth Iter of Antoninus proceeds. It passes a little North of Hedington, coinciding with Wansdike, and just by Calston lime-kiln is parted from it, and proceeds by Rundway-hill. Before it comes to Beckhampton the ridge is very plain and beautiful. It goes South of Beckhampton, lying directly East and North, runs on the South-side of Silbury-hill, and passes Overton-hill, and the visible ridge of it near Abury is a little to the North of the present road. It keeps afterwards on the North-side of the river Kennet till it comes to Marlborough.

Note 3. Itin. I. 132.

Dr. Stukely1 [sic] places VERLUCIO (which the Itinerary makes 15 miles from Bath) at Hedington, which is too far from Bath, and too near Marlborough. Dr. Gale2 had therefore placed it at Westbury, which is indeed off the military way, and in a MS note he translates it Ver lug, the town on the Were. But Mr. Horsley finding the present distance between Bath and Marlborough agree[s] with the Itinerary distance between AQUAE SOLIS and CUNETIO, Mr. H. chooses to divide it proportionably to the numbers in the Itinerary, and concludes VERLUCIO to be near the part where we are directed to by such division. By this method, 15 Itinerary miles will bring us to the East of the river Avon, though not very much. There is a place called Aldford, through which the way to the ancient ford may have lain. Leckham on the Avon, though somewhat out of the line of the way, as Dr. Stukeley represents it, may seem to retain somewhats of the name VERLUCIO; and there we are told by Mr. Camden3, Roman coins are frequently found. Lacocke is also not far from it, and much in the line of the military way; and near this last place Leland4 mentions "a field called Silverfield, where men find much Roman money." Mr. Horsley therefore makes no great doubt but that VERLUCIO has stood in the neighbourhood of one of these places, though perhaps on the other side of the river. Dr. Stukeley, in his Comment on Richard of Cirencester, places VERLUCIO at Lacocke5.

Note 1. Itin. I. 134.

Note 2. Anton. Itin. p. 134.

Note 3. Brit. Wilts.

Note 4. It. II. 29.

Note 5. P. 55.

The discovery of such considerable vestiges of a Roman villa at Mansfield-Woadhouse, in a part of Nottinghamshire where "there certainly never was any Roman Road6," will justify us concluding in favour of another Roman villa near Warminster, which is within 20 miles of a very considerable military way. The same articles present themselves in both villae: pavements, hypocausts, rings, horns, styles, coins. It is by no means improbable, that, at the distance which Warminster is from Bath, some Roman of distinction may have fixed his double villae, as well as others of his countrymen at Mansfield-Woadhouse, or as those who left marks of their magnificence and taste at Wellow near Bath7, at Nether-Hayford8 near Weedon, at Welton9 near Geddington, or at Cotterstock10 near Oundle, all in Northamptonshire, and not much nearer to stations; or those at Winterton and Roxby in Lincolnshire11, where no station has been discovered, though the Fosse Road ends at the first of these places, or that at Hovingham near Castle-Howard in the North Riding of Yorkshire12, or that most beautiful, but now entirely destroyed, one at Littlecoat, six miles from Marlborough, which seemed to have formed the floor of a temple13, and that smaller in Ridge coppice, near Froxfield, in the same neighbourhood14; all which are so many proofs that such monuments are not confined to stations, but scattered all over the kingdom, by the people who first conquered, and then civilized it, and kept possession of it 476 years.

Note 6. Major Rooke, Arch. VIII. 375.

Note 7. Engraved by this Society, Vet. Mon. I. pl. i.—lii.

Note 8. Moreton, 528. Bridges, I. 519.

Note 9. Drawn by John Lens, and engraved by Cole, at the expence of Lord Viscount Hatton, who preserved it by building over it.

Note 10. Engraved by this Society, Vet. Mon. I. xlviii.

Note 11. Engraved by this Society, Vet. Mon. 1750, II. ix.

Note 12. Engraved by Vertue, for the Earl of Burlington, 1747.

Note 13. Engraved by Mr. Vertue, with an account by Professor Ward, 1729.

Note 14. Engraved by Vandergucht, 1723.

Mr. Camden did not hesitate to place VERLUCIO at WARMINSTER, deriving both names from the Deveril, on which the latter town stands, whose name he compounds of the second syllable of that little name and the Saxon word [transcription to be completed]. It was formerly famous for its particular privileges, being excused in the Conqueror's survey from every tax (nec geldavit nec hidata fuit [translation to be completed]), though in Mr. Camden's time only noted for its corn market. The course of the Road seems against Mr. Camden, but not perhaps against Dr. Salmon placing VERLUCIO at Devizes15. R. G. [Richard Gough]

Note 15. P. 790.

SINCE the above was printed off, Mr. BARRINGTON received the following letter from Mrs. DOWNES, dated Warminster, March 10, 1788; in which, after expressing her acknowledgements for the attention paid to her description by the Society, she proceeds.

"Give me leave, Sir, to mention to you a small inaccuracy of the press in regard to the Lecturer in Philosophy; for Walker, read Warltire: the mistake was natural, as there is a Mr. Walker, a Lecturer also.

Not long since there was accidentally found, in some of the rubbish at Pitt Mead, a small, but perfect copper coin of Claudius, with a radiated crown, and also some quantity of burnt corn in a hollow stone. All farther intention of search there is, I believe, dropped, which I cannot but regret; as, I am certain, the parts hitherto unexplored are full as likely to contain wherewith to gratify the curious as those already opened. But Lord Weymouth having taken the matter into his hands, excludes any one else from attempting discoveries.

I cannot help observing to you, that at the distance of about half a mile north of Pitt Mead, and nearly upon a line with it, stands Battlesbury, a triple intrenchment, upon which Roman coins have been found, one of the first Constantine lately; and from this place a chain of intrenchments may plainly be traced for nine or ten miles towards Marlborough; and about a quarter of a mile south of Pitt Mead, on a rising ground called Sutton Common, is a circular level plain, about thirty yards over, inclosed by a bank four feet high, with two entrances, one east, the other west; and in the neighbourhood of Pitt Mead are several tumuli or barrows: and great numbers of Roman coins have been found, at different times, near to all these spots, many of which I have in my possession. With all due submission, do not these things bespeak something more than a mere VILLA at Pitt Mead or Warminster?

Many apologies are necessary for the length of this letter; but I shall forbear to trespass longer upon your patience: and have the honour to subscribe myself, with the greatest respect, Sir, your most obedient servant, CATH. DOWNES."