Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7 Pages 145-191

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7 Pages 145-191 is in Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7.

Silbury [Map]. By the Rev. A. C. Smith, M.A. Read before the Society at Avebury during the annual Meeting at Marlborough, September, 1859-

"Unchanged it stands: it awes the lands

Beneath the clear dark sky ;

But at what time its head sublime

It heavenward reared, and why —

The gods that see all things that be

Can better tell than I."1

Note 1. Bode's Ballads from Herodotus, p. 102.

Living as I do, though not quite under its shadow, yet within sight of Silbury, I feel in some degree locally constituted its guardian, and if I hear of any one impugning its purpose, or in any way speaking disrespectfully of the great mound, I have such a wholesome dread of incurring the wrath of the " [protective spirit]," that I consider myself in duty bound to act in some sort as its champion, and rebut any such accusations to the best of my power. Moreover esteeming it as one of the most remarkable and interesting relics of antiquity in this or any other County, and entertaining a strong belief that it contains the remains of the mighty dead of a very early age, I am very desirous to rescue it from the imputation of having been raised for other than sepulchral purposes, under which it has lain since the year 1849, when Mr. Tucker, who drew up the report of its examination by the Archaeological Institute boldly concluded his paper by announcing the sepulchral theory to be henceforth exploded.1 From such an assumption I must beg leave to dissent, and I hope to prove that here Mr. Tucker has jumped too rapidly to a conclusion, which is hardly warranted by his premises; and while I enter my humble protest against it, I imagine that I do not stand alone, but am only echoing the sentiments of very many, and some of these no mean Archaeologists, among whom I am proud to enumerate Aubrey and Stukeley of old time, and of our own day, the late Dean of Hereford, and that prince of Anglo-Saxon scholars, the late Mr. Kemble ; both of whom (unless I very much misunderstood them at the time) as well as many other influential members of the Institute who were present on the occasion, gave it as their opinion, not that the sepulchral theory as regarded Silbury must be abandoned, but only that we failed to prove it to be something more than theory, by not being so fortunate as to hit upon the exact spot in our excavations.

Note 1. Salisbury Volume of the Proceedings of the Archaeological Institute for 1849, p. 303. Archæological Journal, vi., 307.

With considerable diffidence of my own knowledge of the subject, but backed by such well-known names, I proceed to give a short description of the great tumulus, and then to consider its probable origin: remarking by the way, that gigantic as the work is, we can find no allusion to it in any early writer, unless we accept the suggestion (for which there seem to be scarcely sufficient grounds,) that possibly the "heaping the pile of Cyvrangon" mentioned in the Welsh Triads, as one of the three mighty labours of the island of Britain, may be applied to Silbury.1

Note 1. Sir R. C. Hoare's Ancient Wilts, ii., 83. Davies' Celtic Researches.

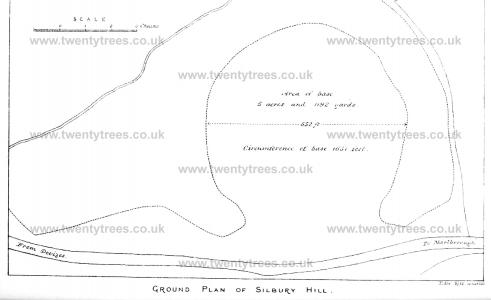

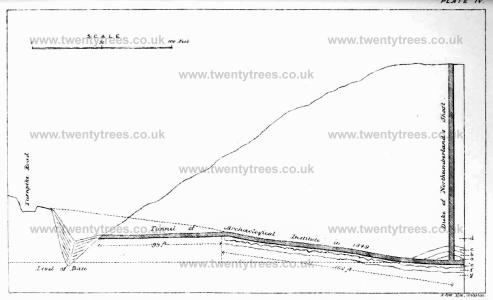

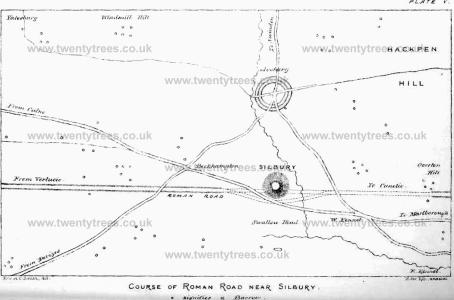

Silbury stands on the extreme edge of a short spur or promontory of down, jutting out Northwards towards Avebury, and is nearly South of the great Circle, and midway between the extremities of the avenues:1 that is, assuming that there was a second avenue, and that it ended where Stukeley fancied. Its general mass is composed of chalk, earth, and rubble taken from the surrounding soil, and is covered with the short close turf for which our downs are so famous:2 but by the kind assistance of Mr. Cunnington (who also furnished me with some of the details of the accompanying section) I am enabled to give an accurate description of the component parts of the hill, as they were originally placed in situ by the workmen (whoever they were) and as they were revealed by the tunnel which penetrated to the centre in 1849 under the auspices of the Archaeological Institute.3 It will be seen that at the nucleus of the mound these several materials lie in regular layers, (or segments of concentric circles)2 as they must have been taken from the surrounding ground and there deposited : the curve of the strata plainly showing the commencement of the accumulation, by which this gigantic tumulus had been formed:5 thus we have

1st, (at a) Light rubble with flints and chalk.

2nd, (at b) Dark clayey rubble with flints.

3rd, (at c) Decayed peat with moss and shells.

4th, (at d) Light chalky rubble, forming the general mass of the hill.

Note 1. Stukeley' s Abury, p. 41. "Abury illustrated," by William Long, Esq., M.A., in Wiltshire Magazine, vol. iv., p. 337.

Note 2. Professor Buckman found forty species of plants on Silbury Hill, and considers that it furnishes a good, example of the flora of a limestone district.

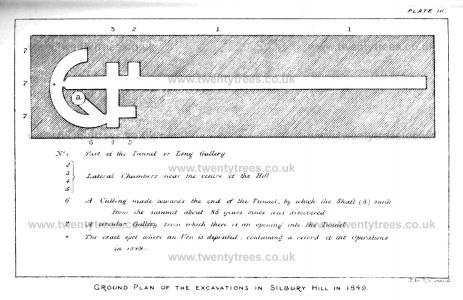

Note 3. "On Tuesday the 10th July the excavation of the gallery was commenced : from this time gangs of workmen succeeded each other at stated intervals, so that the work proceeded day and night without interruption. By Friday evening the 13th, the tunnel had extended to 94 feet from the entrance, about one-third of the whole intended length, by which it was calculated the centre of the hill would be attained. The work thus far was carried through the natural soil, a vein of hard undisturbed chalk, and proceeded in an upward direction, at an inclination 'of 1 in 28 : the artificial soil was cut into at 33 yards from the entrance : the work was then carried on through 18 inches of the artificial earth and 5 feet of the original soil, presuming that by this means any sepulchral remains must be discovered if they existed. The excavation was carried in this way 54 yards, at which distance, according to the survey made, the original centre of construction, or true centre of the hill would be attained." [Examination of Silbury, in Salisbury Volume, p. 300.]

Note 4. Archaeological Journal, vi., 307.

Note 5. "The turf was quite black, as was also the undecayed moss and grass which formed the surface of each layer, and amongst it were the dead shells, &c, such as may still be found in the adjoining country." [Salisbury Volume of the Archaeological Institute, p. 301.]

Nor is this all which the tunnel has revealed, for it exposed the undisturbed surface, just as it existed before the vast superincumbent mass was placed upon it, showing throughout its entire length,

1st, (at e) The ancient original turf.

2nd, (at /) The original soil (viz : clay with flints).

3rd, (at g) The original chalk undisturbed.

So far for its geology. Next with regard to the Etymology of Silbury. Here, as in everything else connected with this mysterious tumulus, there is a great variety of opinion, some inclining to the tradition that a King Sel was buried here, and thence its name;1 others, that it is "Solis-bury," the mound of the Sun:2 but the most obvious derivation seems to be from the Anglo-Saxon words sel "great, excellent," and bury "mound," just as Silchester undoubtedly derives its name from sel "chief" and ceaster, "city;"3 and Selwood is described by the Saxon Chronicler Asram as "Magna Silva." And in good truth an enormous mound it is, and correctly stated by Mr. Matcham in his paper on the results of Archaeological investigation in Wiltshire, "the largest tumulus which this quarter of the world presents."4

Note 1. The tradition was that King Sel or Zel was buried there, and that the vast mound was raised while a posset of milk was seething. [Hoare's Ancient Wilts, ii., 80. Abury illustrated, in Wiltshire Magazine, vol. iv., p. 337. II Stukeley's Abury, p. 42.]

Note 2. Rickman (who disdains the idea of sepulture as connected with Silbury) enters into a long and ingenious argument, to prove that the latter part of the name, though apparently denoting a memorial of interment there, was applied indiscriminately to every tumulus and hillock, natural or artifical, and is in truth the same as berg, a fact which I do not wish to dispute. [Archaeologia, xxviii., p. 415.]

Note 3. In the county of Westmoreland there is a Raise or large heap of stones, called "Selsit-raise," near Shap : and a How, or heap of earth and stones, near Odindale, called "Sillhow," [Archaeological Journal, No. 69, 1861]. [See Bosworth's Anglo-Saxon Dictionary in loco.] In like manner Stukeley supposes that the old British or Belgic name of Stone-henge " Choir-gaur," latinized by the monks into "chorea giganteum" signifies " the great Church," or, as we should say, the "Cathedral." [Stonehenge, p. 47.]

Note 4. [Salisbury Volume of the proceedings of the Archaeological Institute in 1849, p. 5.] The author of the "Lost Solar System of the Ancients discovered," calls it, "the largest tumulus in Europe, and one worthy of comparison with those mentioned by Homer, Herodotus, and other ancient writers," [i. 417]. I [Sir R. Hoare's Ancient Wilts, ii., 81.]

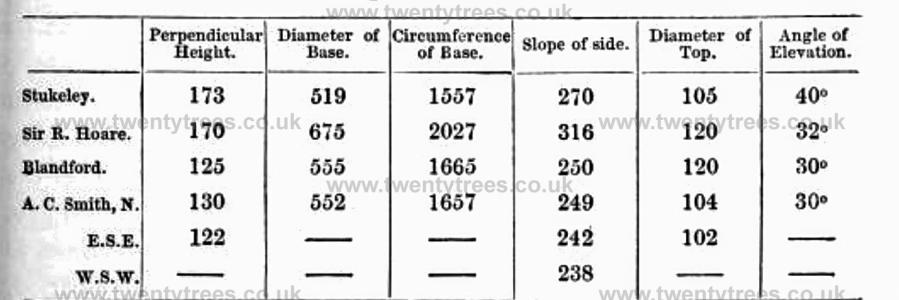

It is extraordinary that though its dimensions have been often published, no two measurements have ever yet proved alike: under these circumstances I hardly dare assert my own accuracy, though from repeated measurements with the spirit level, the quadrant and the tape, I have satisfied myself that I have mastered its dimensions: and I cannot but conjecture that the fact of its circular form giving it the appearance of far greater steepness than in reality it possesses, has caused some to doubt the accuracy of their own measurements, and led them to trust to their eye rather than the tape; though by standing at some distance and holding up a stick obliquely between the eye and the slope of the hill, any one may easily satisfy himself that the angle of elevation is far lower than he would at first sight have imagined. I proceed now to compare the measurements of Stukeley who surveyed it circa A.D. 1720;1 Sir Richard Hoare about A.D. 1812;2 Mr. Blandford in 1849, and my own of the present year, as regards Perpendicular Height; Circumference of the base; Diameter of the base; Diameter of the top; Slope of the side; and Angle of elevation:3 first remarking that with the single exception of the comparatively immaterial measurement of the Diameter of the top, Mr. Blandford's figures coincide very nearly with my own, though we both differ widely from those of the above-named eminent Antiquarians.4

Note 1. Stukeley's Abury, p. 43.

Note 2. Sir R. Hoare's Ancient Wilts, ii., 82.

Note 3. Rickman, (in the 28th vol. of Archæologia,) gives 2300 feet as the circumference of the base; 105 as the diameter of the top; and 130 as the perpendicular height, the two latter figures agreeing with my own: but the former (if correct), would produce an area of 10 acres and 538 yards, whereas Hickman says, it covers only 4½ acres, wherefore there is a manifest discrepancy in his figures.

Note 4. In taking the present measurements, I have not only been very much assisted by my friend the Rev. W. C. Lukis: but his name is a further guarantee that no mistake has been made : and in working out the figures, and calculating the contents of the hill, I desire to record my obligations to Mr. Richard Falkner of Devizes, who has kindly come to my aid, and has also given me much valuable information on many points connected, with my subject.

With regard to the slope of the side, and the diameter of the top, which aro so easily measured, and especially in the latter case, which requires no calculation, and where the line extends from one side to another, one would imagine that with ordinary care no discrepancies could exist, and yet it will be seen by the table that the measurements here vary quite as much as elsewhere. And with regard to the angle of elevation which Stukeley boldly affirms to be 40°,1 I would again observe, that in this the eye greatly deceives us, leaving us under the impression that the sloping side is far steeper than it really is, and while I confess that on paper our hill does look very depressed, and very easy of ascent, I would deprecate the criticism of the casual observer, and beg him before he condemns my figures, to give them the only fair trial of their accuracy, viz : a personal examination.

Note 1. I must add that Dr. Stukeley, though, an accomplished scholar, was by no means accurate in his figures and plans.

So much then for its dimensions, though I may add that the ground covered by this gigantic tumulus has been variously estimated at from five to six acres.1 According to my measurements, the area of the base would be 5 acres and 1192 yards, and its cubical contents 468, 170 cubic yards.

Note 2. Sir Richard Hoare says 5¼ acres: (Anc: Wilts, ii., 82). Rickman only 4½ acres: (Archaeologia, vol. xxviii., 402). Stukeley adds "the solid contents of it amount to 13, 558, 809 cubic feet: some people have thought it would cost £20,000 to make such a hill." [Abury described p. 43,] and Aubrey says, "I remember that Sir Jonas Moor, Surveyor of the Ordnance, told me it would cost threescore, or rather (I think), fourscore thousand pounds to make such a hill now."

And now I think I may assert without fear of contradiction that Silbury was a work of enormous labour, and at the early period of its formation must have taxed the sinews as well as the patience of a vast multitude ; and though in this advanced age, and in our superior wisdom, we are (I think) somewhat inclined to underrate the powers of our rude forefathers in a remote period, and decry their skill, (though surely in Wiltshire at least Stonehenge and Avebury and Silbury stand before us to rebuke our self conceit, and arrest our supercilious contempt for bygone ages) yet without arrogating to barbarous times the skill of modern engineers, and the appliances of modern science, we may rest assured that those who directed the throwing up of Silbury were not wanting in courage and ability to accomplish so mighty a work;1 for without question a mighty work it was, and especially if we consider that in all probability every particle of it was carried in baskets on the shoulders of the workmen, as was and is the custom of barbarous nations:2 though I confess it dwindles down to the comparative insignificance of a mole-hill when placed side by side with the gigantic results of railway embankments within the last thirty years, so graphically described in a recent article in the Quarterly.3 There we are told that it is almost impossible " to form an adequate idea of the immense quantity of earth, rock and clay, that has been picked, blasted, shovelled and wheeled into embankments by English navvies during the last 30 years : on the South Western Railway alone the earth removed amounted to sixteen millions of cubic yards, a mass of material sufficient to form a pyramid 1,000 feet high, with a base of 150,000 square yards. Mr. Robert Stephenson has estimated the total amount on all the railways in England as at least 550 millions of cubic yards, and what does this represent ? " We are accustomed," he says, " to regard St. Paul's as a test for height and space ; but by the side of the pyramid of earth these works would rear, St. Paul's would be but as a pigmy to a giant : imagine a mountain half a mile in diameter at its base, and soaring into the clouds one mile and a half in height, that would be the size of the mountain of earth which these earthworks would form : while St. James's Park, from the Horse Guards to Buckingham Palace would scarcely afford space for its base."4But to return to Silbury, which we will not attempt to compare to these modern labours. I apprehend it will be allowed on all sides, that it could not have been thrown up without a vast expense of time and severe toil, but at what cost, and whence the workmen derived their supplies of food during their labours,5 it were idle now to speculate : we may also assume that its promoters must have had some great motive, when they set about and accomplished so Herculean a task : and now comes the question, what can we assign as the probable object, likely to have given rise to such a stupendous work ?

Note 1. The grand dimensions of Silbury attracted the particular notice of King Charles II. during a Royal progress to Bath ; and under the guidance of Aubrey the "merry monarch" ascended to the top. [Hoare's Ancient Wilts, ii., 59. Stukeley's Abury, 43.]

Note 2. It is a ridiculous but significant fact that when a railway plant was sent to India from this country, the natives who were employed as labourers in the work, mistaking the use of the wheelbarrows, filled them with earth and then placed them on their heads, and so proceeded to carry them to the embankment they were forming. The same thing is told of the negroes in South America : "they seem to prefer carrying burdens on their heads, transporting the very heaviest articles in this way: it is said that when the railway to Petropolis was being built, the negroes insisted on carrying the handbarrows (which were furnished to them) on their heads, turning the wheel in front with the hand, in time to their song." [From New York to Delhi by way of Rio de Janeiro, Australia, and China, by Robert Minturn : Longman, 1858.] And Sir James Emerson Tennant in his admirable work on Ceylon, says, "the earth which formed the prodigious embankments and Dagobahs in Ceylon was carried by the labourers in baskets in the same primitive fashion which prevails to the present day," [vol. i., p. 464].

Note 3. Quarterly Review for January, 1858.

Note 4. The author of the "Lost Solar System of the Ancients discovered " calculates that in the last fifteen years, 250,000,000 cubic yards, or 400,000,000 tons of earth and rock have in tunnel embankment and cutting been moved to greater or less distances in the construction of railways, [vol. ii., p. 296].

note 5. Compare Herodotus, book ii., chap. 125, where the good old historian delighted to compute the garlic and onions consumed by the workmen at the Pyramids as amounting to 1600 talents of silver, a sum equal to £345,600. [See too Rollin's Anc. Hist., book i., part i., chap. 2, sect. 2.]

I believe that if we search into the existing remains of the most ancient times, and if we continue our enquiries through more mod- ern ages, in heathen countries, we shall find that, almost without an exception, the greatest works of man have been devoted either to objects of religious worship or of sepulture. To accomplish either of these ends, no labour seems to have been too great. As regarded worship, however misguided might be the worshipper, however false the god, the object of providing a suitable temple was enough to smooth away all difficulties, and overcome every obstacle : while on the other hand, to leave behind him a sepulchral monument which should continue as long as time should last, and remain an imperishable memorial of him to distant ages, this was enough to rouse all the energies of the ambitious barbarian, and spur him on to perseverance in the most arduous tasks1. We may take Stonehenge and Avebury as instances of what the first of these motives could effect, while the Pyramids of Egypt, the renowned Mausoleum in Caria,2 and the famous Taj Mahal and other tombs of astonishing size, beauty, and the most elaborate workmanship in India, demonstrate no less clearly the power of the second.

Note 1. The Lost Solar System of the Ancients discovered, vol. ii., 209.

Note 2. Herod., vii., 99. Strabo, xiv. Diod., xvi. Pliny, N. H., xxxvi., 4 — 9. Aul: Gell., xc., 18.

Now to affirm positively, that Silbury was not erected for religious worship, would be to beg the question at issue: moreover we know that the Persians and other Sun-worshippers did frequent the tops of conical mountains, whence they could catch the first beams and watch the last rays of their rising and setting Deity:1 as indeed at this day do the Parsees or Ghebers in the East, and the Peruvians and inhabitants of La Plata in the West,2

"To loftiest heights ascending, from their tops

With myrtle wreathed tiara on their brows."

Note 1. Herodotus Clio, chap. 131. Rollin's Anc. Hist., ii., 136. Job xxxi., 26, 27.

Note 2. "Lost Solar System of the Ancients discovered," vol. i., pp. 260, 265, 395.

Therefore I say it is not impossible that this may have been the origin of the great mound in question : though I confess such a conjecture carries little conviction to my mind: for in the first place, its immediate contiguity to the famous temple at Avebury seems to forbid its intention for such a purpose : and again, stand- ing as it does, on comparatively low ground, and surrounded with undulating downs which tower above it, very limited indeed is the view from the summit, and this fact alone seems to deny that it had any such object.

But against the probability of its being the tomb of some Sovereign or famous Chieftain amongst the early Britons1 I confess I have seen no arguments of any force, while there are many prima facie reasons to induce us to assign this as its origin. For though it is perfectly true that nothing indicating it to be a place of sepulture was discovered, either by the Duke of Northumberland and Colonel Drax, when they sunk their shaft from the top towards the close of the last century,2 or by the Archaeological Institute, when they drove their tunnel into the centre from the side in 1849,3yet I contend that these failures proved nothing more than the unpropitious fortune of the excavators: for if the vast area of the whole mound be considered, and the comparatively narrow passages which pierced it to its centre, like puny bodkins probing a whale,4 surely, (to use a homely proverb,) it was like searching for a needle in a hay-rick, and a marvel it would have been, if without a clue to guide them, they had hit upon the cromlech, always supposing one, or more (for there may be several), to exist.

Note 1. Stukeley goes so far as to assume (though I must own he comes to conclusions on very slight premises) not only that Silbury is the tomb of the Royal founder of Avebury, but that the temple of Avebury was made for the sake of this tumulus : and then he adds, "I have no scruple to affirm 'tis the most magnificent Mausoleum in the world, without excepting the Egyptian Pyramids:" and then giving the reins to his fanciful imagination, he continues, "this huge snake and circle (meaning the avenues and temple of Avebury) made of stones, hangs, as it were, brooding over Silbury-Hill, in order to bring again to a new life the person there buried." [Abury, p. 41.]Douglas's .Nenia Britanniea, p. 161.

Note 2. Douglas's .Nenia Britanniea, p. 161.

Note 3. Without at all impugning the decision of the late Dean of Hereford, who heard their statements, it would have been satisfactory to have learned on what grounds he rejected the testimony of the two old men in the neighbourhood whom he examined, and who both asserted that the miners from Cornwall who dug into Silbury by direction of the Duke of Northumberland in 1777 found "a man," meaning a skeleton. [Salisbury Journal, p. 74.]

Note 4. This is an allusion to a large whale stranded on the coast of Norfolk (of whose death throes I was an eye-witness from a yacht) despatched at last by a ship's spit, after an hour's fruitless attempts on the part of some fishermen to reach some vital part with their short knives. [See Zoologist for 1851, p. 3134.]

Again, however geometrically exact the engineer may have been in driving his tunnel into the exact centre, and however accurately the perpendicular shaft may have attained the same spot, (though by the way they did not meet, for it was in cutting a diagonal passage from the tunnel that the workmen came upon the shaft,)1 yet how improbable is it, that the cromlech would retain its position in the exact centre, assuming for a moment (which I shall presently show to have been unlikely) that it was intended to be near the middle of the mound : for even in this case, those rude workmen, (the "navvies" of a remote age,) as they heaped up their vast tumulus, soon losing sight of the tomb to guide them, would necessarily fail to preserve it as their centre, and the more the mound increased under their exertions, so in inverse ratio the chances diminished of the cromlech retaining its original position in reference to its gigantic covering. Moreover it is not probable that the workmen would have been at any pains to preserve it as a centre, even if it had been so at the first heaping up of the earth.

Note 1. Salisbury Journal, p. 300.

Thus I deny that anything like a satisfactory examination of the interior of Silbury has yet taken place, or that the fruitless researches hitherto made are any proof that it contains no cromlech. And now having answered the only objection put forth against the sepulchral theory, I come to state the arguments I am able to adduce in its favour : and here I would submit, that where absolute proof is wanting, and, (until at least some further research is made) opinions formed can at the last be but conjectures, rendered more or less probable by the arguments adduced, it is quite fair to reason from analogy : and here certainly the countless barrows which stud the downs in every direction around Silbury being them- selves places of sepulture, proclaim the great hill to be the same. I need not stop to prove that to heap a mound of earth over their dead, as a sort of protection to their remains, has been the most ancient and uniform practice of all nations,1 a fact referred to by the oldest extant authors of all countries,2 and of which we have in Wiltshire, and especially on the Marlborough downs more ocular proof than perhaps any where else : and now I would ask, what appearance does Silbury present, but that of a gigantic barrow ? though to to adapt the words of the Roman poet,

"Mieat inter omnes ["Let him be among all]

Silbury collis, velut inter ignes [Silbury hill, as if between fires]

Luna minores. [The moon is smaller.]"

Note 1. The Soros which marks the grave of the Athenian dead is still a conspicuous object on the plain of Marathon. [Wordsworth's Pictorial Greece, p. 113. Leakes Demi of Attica, p. 99. Rawlinson's Herodotus, vol. iii. p. 505.]

Note 2. The following list I have found in an unpublished MS. of Aubrey, and which I have considerably amplified : the figures marked thus (*) being additions to Aubrey's catalogue :

De Tumulis.

Josh : xxiv. 33. vii. 25, 26. viii. 29.

2 Sam : xviii. 17.

Homeri Iliad: ii. *793. 811—815.

vi. *419.

vii. 332—336. *435. *86.

xi. *55. *166. *372.

xvi. *457. 667—675.

xxiii. 245 — 255.

List continues in the original on the following page which is not included here. See original.

And how comes it that the downs round Avebury abound for miles in every direction with such innumerable barrows, but that they form, as it were, a vast graveyard to the colossal temple there, a kind of Mecca where the faithful would desire to lay their bones, a Westminster Abbey in the remote age of the Druids?1

Note 1. "All around Stonehenge are barrows extending to a considerable distance from the temple, but all in view of it, so that like Christians of the present age, ancient Britons thought proper to bury their dead near where they worshipped the Supreme Being." [Spencer's Wilts, p. 79.] Stukeley in his Itiner: Curios: vol. i. p. 128, describing what he supposed to be "Carvilii tumulus," the grave of a king of the Belgse near Wilton, within sight of Stonehenge, says, "I question not but one purpose of this interment was to be in sight of the holy work or temple of Stonehenge;" "and here," he concludes, "rest the ashes of Carvilius, made immortal by Caesar for bravely defending his country." Again, he says, speaking of the vast number of barrows round Stonehenge, "We may very readily count fifty at a time in sight from the place," and again at a short distance off he declares he could count 128 barrows in sight. [Stonehenge, pp. 43,45. Abury, p. 40.] See also " Lost Solar System of the Ancients discovered," p. 113; and Sir R.C . Hoare's Ancient Wilts, i. 250.

But if it be objected that from their inferior size, the analogy of the barrows is of little value, and so to argue from such premises carries little weight, I reply in the first place that many of the barrows which stud our downs are not at all despicable in bulk even now, when the tendency of ages, especially where assisted by the plough, has been materially to diminish their height, and bring them down to the level of the plain : indeed those who have attempted to excavate some of the larger ones will bear me out in my statement, that they are extremely deceptive, and are really very much larger than the casual observer would suppose. But not to insist too strongly on this point, I pass on to the grand climax of my argument, viz., the analogy of other tumuli of colossal dimensions in other countries, which by recent excavations and recent discoveries have been positively proved to be sepulchral. And I would beg of the reader to observe as we pass on, in how many cases the discovery of the interment was the result of pure accident ; how in others their sepulchral character had been denied, till proof positive set the question at rest for ever : and how in several instances the interments were not found in the centre of the mound, but at the side ; for these are all questions nearly affecting the point now under examination, and may materially help us in forming our conclusions on the probable object of Silbury, when we shall have weighed all the evidence I can bring to bear upon it.

The first tumulus which I adduce is in the sister kingdom of Ireland, and is generally known in that country as "New Grange [Map]." It is one of four great sepulchral mounds, situated on the banks of the Boyne, between Drogheda and Slane, in the county of Meath, and which have been not inaptly termed "the Pyramids of Ireland." It is the only one of the four, whose interior has been exposed to human curiosity, but there is every reason to believe that if explored, the others would be found similar in nature to the one in question. I extract the particulars of it from the second vol. of Archaeologia, and the Dublin Journal of March 1833, corroborated by the evidence of my father, who visited it, and made a personal inspection of the interior in 1848.1 It is now (as the learned antiquary Governor Pownall tells us) but a ruin of what it originally was, though it still covers two acres of ground, and has an elevation of about 70 feet ; but its original height was not less than 100 feet, as it has been used for ages as a stone quarry, for the making and repairing of roads and the erection of buildings in the neighbour- hood. It is formed of small stones, covered over with earth, and at its base was encircled by a line of stones of enormous magnitude, placed in erect positions,2 and varying in height from four to eleven feet above the ground, and supposed to weigh from ten to twelve tons each : these stones as well as those of which the grand interior chamber is built, are not found in the neighbourhood of the tumulus, but have been brought hither from the mouth of the river Boyne, a distance of seven or eight miles. The interior of the tumulus, was accidentally made known in the year 1699, when a Mr. Campbell, who resided in the neighbouring village, in carrying away stones from it to repair a road, discovered the entrance to a gallery or passage leading into a sepulchral chamber. This entrance was about 50 feet from the original side of the Pyramid, and is placed due South, and runs Northward: the length of this passage to the entrance of the chamber is about 58 feet, its breadth and height gradually narrowing till at about 18 feet from the entrance it reaches a stone which is laid across in an inclined position, and which seems to forbid further progress : beyond this, the gallery immediately expands again to the width of three feet, and to the height of from six to ten feet at the entrance of the dome. The chamber is an irregular circle, about 22 feet in diameter, covered with a dome of a bee-hive form, constructed of massive stones laid horizontally and projecting one beyond the other, till they approxi- mate and are finally capped with a single one : the height of the dome is about 20 feet. The chamber has three quadrangular recesses, forming a cross, one facing the entrance gallery, and one on each side : in each of these recesses was placed a stone urn or sarcophagus, of a simple bowl form, two of which remain to this day : of these recesses the East and the West are about eight feet square, the North is somewhat deeper. The entire length of the cavern from the entrance of the gallery to the end of the recess is 81 feet 8 inches. The stones of which the entire structure consists are of great size, viz., from 12 to 18 feet long by 6 broad ; a great number of the stones within the chamber, as well as in the gallery, are carved with spiral, lozenge-shaped, and zig-zag lines, and in the West chamber there are marks, which have been supposed, though perhaps without reason, to be an alphabetic inscription. That this large tumulus was constructed "as a tomb or great sepulchral pyramid" and that the "oval granite basins originally contained human remains" admits of no doubt: and as to its age, by most of the learned and intelligent modern archaeologists it is referred to the most remote period of Celtic occupation, and far beyond the time of the invasion of the Danes, to which people, like so many other Irish antiquities, it has been sometimes attributed ; indeed it is generally supposed to be coeval with, by some to be even anterior to, its brethren on the Nile."3 Such is the remarkable tumulus of New Grange in Ireland, apparently the very counter- part of Silbury : and I have been thus minute in giving all the particulars I could glean, and especially the exact position, with reference to the points of the compass, of the chambers and gallery, because I am not without hopes that they may hereafter be useful to some future investigators of Silbury which perhaps may be found to contain similar treasures.

Note 1. See Mr. Edward Lhwyd's description of it, in a letter to Mr. Rowlands at the end of Mona Antiqua; and that by Dr. Thomas Molineux, published first in the Philosoph: Transactions No. 335 and 336, and afterwards in his discourse on Danish forts in Ireland : above all, see Governor Pownall's description in the Archaeologia, vol. ii. pp. 236 — 275. Also Journal of Archaeological Institute, iii. 156. Stukeley's Itinerarium Curiosum, plate in vol. ii. p. 43. Dublin Penny Saturday Journal, vol. i. p. 305.

Note 2. In the Salisbury vol. of the Proceedings of the Archaeological Institute in 1849, p. 74, Dean Merewether in speaking of Silbury, says, "It is remarkable, though I have not seen it noticed by former writers, that the verge of the base is set round with sarsen stones, three or four feet in diameter and at intervals of about eighteen feet ; of these however, only eight are now visible, although others may be covered with the detritus of the sloping sides of the tumulus, and overgrown with turf." This is clearly a mistake, though it is astonishing how the Dean, usually so careful, fell into such an error, for there is, and there has been for very many years, but one small stone visible on the Northern side of the base. [See Mr. Long's "Abury Illustrated" in Wiltshire Magazine, vol. iv. p. 339.]

Note 3. Compare Mr. Scarth's account of this tumulus in his very able paper on "Ancient Chambered Tumuli," published in the 8th vol. of the Proceedings of the Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society: Taunton, 1859, pp. 24—27.

The next great mound to which I wish to direct attention, and this too externally bearing an exact resemblance to Silbury, is the largest of all the tumuli in Britany, the "Tumiac," situated at the South of that Province, near the end of the promontory in which Sazzeau is situated, and on the road to Arxon. It is about 280 feet in diameter, and 68 feet in height ; or, to speak more accurately, it measured, according to the French style, 260 metres in circumference, and 20 metres in height, the metre being, (as it is almost needless to state) within a fraction of 40 inches English. Up to 1853 it had baffled the curiosity of antiquaries no less than Silbury has done to the present day, and then accident alone led to the discovery of a large sepulchral chamber on one side, for there was nothing to indicate the spot. This discovery took place in July of that year, under the auspices of the Societe Polymatique, who opened a gallery at the base of the mound due South, or rather one point East of South. The entire mound proved to be composed of small stones or large pebbles thrown together, and through these the tunnel penetrated in a straight line running N.N.E. to the distance of about 140 feet, and then reached a square chamber, at a considerable distance from Us centre, though far into the interior of the mound. This chamber was formed of three large granite pillars, placed sideways on a bed of stones supporting a large flat slab of quartz which formed the roof of the cromlech. On the sides of some of these stones, characters were to be traced, some- | what of a Syriac or Arabic form, though their meaning still re- mains an enigma not to be deciphered : within the chamber, which was exceedingly damp, the water continually dropping from the upper stone, was found a layer of dark dust, evidently the remains of decomposed wood ; buried in which were 120 round beads, which probably formed a necklace : and in another part about half that number of larger round beads of jasper, which were supposed to have composed a bracelet. Two groups of celts, or Druidicai knives, fifteen in each group, were also discovered here ; some highly polished and of great beauty, though the greater part were ; broken in two pieces. But to crown all, several fragments of bone ! were also found, which, though almost pulverized and in a very decomposed state, were identified by scientific anatomists to whom they were submitted, as undoubtedly human : indeed there were sufficient portions to indicate pretty clearly that the corpse was laid on a wooden plank at the end of the chamber along the North wall, the head to the East, and the feet towards the West. The accident which led to the discovery of this chamber was as singular as it was happy, for with nothing to guide them, the directors of the excavations pushed their tunnel right up to the very entrance of the chamber, whereas had they gone one point more to the East or West, they would have missed the only entrance to it, if not , the cromlech itself. The above particulars I have taken from the Report, drawn up by M. Fouquet, the Secretary of the Societe Polymathique, and addressed to the Prefet of the district:1 and I have the greatest satisfaction in bringing forward this instance, I both because my friend, the Rev. W. C. Lukis, chanced to be i present soon after the discovery of the sepulchral chamber, and was an eye- witness of the particulars I have given above : and also because the fact of the sepulchre being at the side, speaks volumes to my mind with regard to Silbury, accounts for the failure of former investigators, whose whole energies were directed towards the centre, and suggests that it is no cenotaph, but still contains ; one or more tombs, to reward the perseverance of future excavators.

Note 1. Rapport sur la decouverte d'une Grotte Sepulcrale dans la butte de Tumiac le 21 Juillet 1853, adresse a Monsieur le Preftt du Morbihan, au nom de la Societe Polymathique par le Secretaire de cette Societe le l er Aout 1853.

From Britany I pass through North Germany, remarking on the numerous barrows of various form and height which abound there, and are denominated "Kegelgraber," conical graves,1 whose sepulchral object has never been called in question; but which, as they do not rival Silbury in bulk, I will not adduce in support of my argument. Thence I proceed to Northern Europe, and call attention to the large tumuli there, some of which are of such vast dimensions and adorned with such enormous blocks of stone (wherein the Northmen especially delighted) that they are still regarded by the natives as of stupendous magnificence:2 it haa never however been disputed there, that these are the tombs of the mighty dead, (whose souls wander, and whose shades drink mead out of the skulls of their enemies, in the halls of Valhalla) though I am not aware that any of the larger ones have been explored Therefore I merely allude to them as we hurry by, but above all, I would point out as more particularly deserving of notice the great mounds of old Upsala, the sepulchres of the ancient "gods of Scandinavia" as they are called, the graves of Odin, Thor and Freya.3

Note 1. Archaeological Journal, xii., 387.

Note 2. Archaeologia, vol. ii., p. 264. Monum. Dan., lib. i., c. vi. Monumenta Sueo-Gothica, lib. i., pp. 215—217.

Note 3. Northern Travel by Bayard Taylor: London, 1858, p. 17. See Murray's Handbook for Northern Europe, vol. ii.

[Continues at length discussing European, Egyptian and South American monuments.]