Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7 Pages 315-320

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7 Pages 315-320 is in Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7.

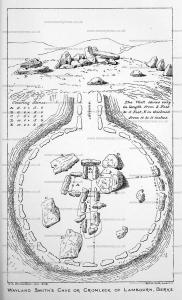

Wayland Smith's Cave or Cromlech [Map], near Lambourn, Berks. By Professor T. L. Donaldson, Architect, Ph. D.

Those, who are accustomed to travel along the line of the Great Western Railway, will remember a range of downs, which on the south skirts the vale beyond the Steventon station. Near the Shrivenham station is the White Horse Hill. A series of downs runs from east to west for 30 miles or more, covering a breadth of some 12 or 15 miles. These downs rise to a considerable height, and have a series of undulations and valleys, which diversify the face of the country and give it a varied character. The geologist, the architect, and the antiquary, have here full scope for their respective pursuits. The summit of the White Horse Hill is crowned by a regularly formed fortification, by some called the Camp of Alfred, by others considered a Roman encampment. Ashdown Park, the seat of Lord Craven, and the production of Inigo Jones, lies in the very heart of the downs, about three or four miles from Lambourn. On these wild expanses, unbroken by divisions of fields, undivided by roads, are scattered in some parts a profusion of Boulders, while other spaces close by are quite free from them. These masses of rocks sometimes contain three or four tons of stone each, but others are round and smaller. These are used by the farmers to form walls, and are broken in pieces for that purpose by having a fire lighted under them, so that they become quite hot ; cold water is then thrown upon them, and they split and fall to pieces. In the times of the Early Britons, the Druids constructed of such blocks their Dolmens, the Cairns, the Triliths, the Cromlechs and Rocking-stones, which abound in this country, and are found as well in Gaul, Germany, and even Spain. These rude constructions owed their origin to such regions as this range of down, where frequent Boulders (possibly the glacial deposits of antediluvian epochs) offered ready materials to the piety and energy of the Celtic worshippers.

Sir Walter Scott, whose antiquarian lore is so well known, avails himself of this rude mound as a feature in his novel of "Kenilworth," where Tressilian, anxious to replace a lost shoe to his horse, is taken to it as Wayland Smith's Forge, a traditionary name of long standing. "Here are we," said Dickie, "at Wayland Smith's Forge-door." "You jest, my little friend," said Tressilian ; "here is nothing but a bare moor, and that ring of stones with a great one in the midst like a Cornish barrow."

"Ay, and that great flat stone in the midst, which lies across these uprights," said the boy, "is Wayland Smith's counter, that you must tell down your money upon."

"What do you mean by such folly?" said the traveller, "beginning to be angry with the boy, and vexed at himself for having trusted such a hare-brained guide."

"Why," said Dickie, with a grin, "you must tie your horse to that upright stone, that has the ring in't, and then you must whistle three times, and lay me down your silver groat on that other flat stone, walk out of the circle, sit down on the west side of that little thicket of bushes, and take heed you look neither to right or left for ten minutes, or so long as you shall hear the hammer clink, and whenever it ceases, say your prayers for the space you could tell a hundred, or count over a hundred, which will do as well, and then come into the circle, you will find your money gone and your horse shod."

Lysons, in his "Magna Britannia," vol. i., p. 215, gives a plate of the White Horse Hill, and in the corner a rudely drawn small view of the Cromlech, which he calls "Way land Smith." There are no trees around it. More covering stones appear to be in their places, and earth seems piled up against the central stones. He calls this a "tumulus, over which," he says, "are, irregularly scattered, several of the large stones, called Sarsden Stones, found in that neighbourhood; three of the largest have a fourth laid on them in the manner of the British Cromlechs. It is most probable that this tumulus is British."

Were it not for the unusual size of the covering stones, and the reputation it has justly acquired, this ruin might escape notice. When we, however, come to examine its arrangement more narrowly, its form and disposition immediately class it among the most important monuments of its kind. The central figure has the form of the Latin Cross, the whole length being some 22 or 23 feet from out to out; its greatest width 15 feet. Each end of the four arms of the Cross is closed by a larger sized stone from 5 to 7 feet long and 15 to 24 inches thick, the longer arm answering to the nave of a church is 2 feet wide inside and 14 feet long, having now on one side four blocks, and on the other three ; but I am inclined to think one has been displaced, and that there were four on that side also. These stones forming the walls are 14 or 15 in number, and vary from 3 feet long to 4 feet. The shorter arms or transepts are about 5 feet wide, and they are 5 feet deep, thus presenting the appearance of chambers 5 feet square, with the entrances narrowed to 2 or 3 feet. The short arm at the further end is 4 feet 9 inches deep by 2 feet wide, and is formed by a stone on each side and one at the end.

There were five large blocks to form the roof: one now remains in its place, covering the east transept ; it is of circular form 10 feet by 9 feet on the surface, and 12 inches thick ; it therefore weighs from 5 to 6 tons. The covering block of the other arm or transept is 9 feet long by 5 feet wide : that at the further end 6 feet by 5 feet ; the two, which covered the nave, respectively 7 feet 6 inches by 5 feet wide, and 10 feet long by 5 feet wide, and of the same average thickness.

At the distance of 15 feet from the end of the eastern transept are three stones in their places, corresponding in size with the wall stones of the centre group, and varying from 3 feet 9 inches to 5 feet long. They seem to form the arc or portion of a circular out- side ring. Although there are only two or three other stones of this size to be found on the site, I am led to think that these three stones formed a part of an enclosure, and that the rest have been removed by the peasants. The general arrangement, then, of this interesting remain would present a mound about 50 feet in diameter at the top, surrounded by an outer ditch ; the top of this mound having a circle of stones, in the centre of which is a cruciform chamber in the shape of a Latin Cross, there being one arm to the south decidedly longer than the others. On examining the ground opposite the north end, it appeared to me as though there was a continuous embankment, calculated for an alley of stones, or a dromos, as at Avebury, near Marlborough. And here, possibly, was an opening in the outer ring affording access to the enclosure. The whole of the mound and a considerable distance, where I suppose the avenue to have been, were some years since closely planted with fir-trees, so that it is not without considerable care that the precise form of the whole can be guessed. The species of gallery with the two lateral chambers, which the general form presents, is very like the galleries of New Grange, Wellow, Pornic, and the Galgaloi Gavrennes: but these were all embedded in mounds, which Wayland Smith's Cave has never been. The outer circle of stones immediately raises it to the dignity of those gigantic Cromlechs (magna componere parvis) of Stenness in the Orkneys, Landaoudec in Crozon, at Carnac near Auray, in Morbihan, France, 20 miles to the S.E. of l'Orient, Stonehenge and Avebury in Wiltshire, with this exception, that the inner constructions were there circular, instead of being cruciform as in this instance. (See Gailhabaud, "Monumens Anciens et Modernes," article "Monumens Celtiques," 1840 — 50.)

I leave it to others, more versed than myself in Celtic antiquities, to decide the actual destination of this monument of our forefathers. May I presume to suggest, that the centre m&y have contained the remains of one or more deified persons held in high veneration ; that the whole enclosure was dedicated to public worship ; and that perhaps the covering stones themselves served as altars, and on them were possibly offered the human victims, sacrificed to propi- tiate the manes of the dead, or to appease by their bloody rites the wrath of the savage gods of the Druid Priests. T. L. D.

At the conclusion of the paper Mr. Lukis said that, while expressing what he felt sure was the sense of the meeting, viz., that the best thanks of the Society were due to Professor Donaldson for his interesting communication, there were two or three points in it, which invited discussion.

In the first place there was an allusion to the origin of Boulders which he, Mr. Lukis, would leave to the geologists present to explain. In the next place there was the form of Wayland Smith's Cave, which the Professor, in his admirable and accurate ground plan, had shown to be a Latin Cross. This Mr. Lukis conceived to arise from an accidental circumstance. It was well known that Cromlechs not unfrequently had side chambers subsequently added to them. This may be seen in the published plans of New Grange, and other Cromlechs, in the instance before us, as well as in that of Du Tus, in Guernsey, and in those which abound in Britany and Scandinavia. The Professor exhibits a ground plan of a fine Cromlech on Lancresse Common, in Guernsey, in which a similar chamber is marked ; but that one, which Mr. Lukis explored in conjunction with his brothers in 1838, for the first time, barely amounts to more than a small recess. These chambers, Mr. Lukis conceived, were additions subsequently made, sometimes on one side only, at other times on both sides of the original central construction. Here, at Wayland Smith's Cave, there was a chamber on both sides ; but the reason for their being opposite to each other, and in the centre of the main line, so as to form with it the other limbs of a Latin Cross, was apparent. The side chambers are proportionably larger than the central one, and required to be inclosed in that part of the barrow where they would be most covered with earth. In a mound of comparatively small dimensions, the centre would present the only favourable position.

Again, Professor Donaldson seems to consider that this monument was never inclosed in a mound of earth. This, Mr. Lukis stated, was not his opinion. On the contrary he believed not only that Wayland Smith's Cave had been inclosed in a barrow, but that all Cromlechs were originally so inclosed. He did not think that there was any evidence to disprove this statement. All the Cromlechs he had seen, and he had carefully inspected and examined many in different parts of Europe, had confirmed his opinion. They were, in fact, sepulchral vaults inclosing the ashes of the dead, which have boon in all ages respected and carefully protected from the rude hands of men. The very fact of such gigantic labours having been bestowed upon their erection is a proof of the reverence they felt for the mortal remains of their friends. It was not likely, therefore, that they would have erected chambers for their reception, open not only to the light and to the elements, but to the irreverent gaze and treatment of different and hostile tribes.

And this would lead him, (Mr. Lukis,) to touch upon one other point, viz., his entire disbelief in the use and appropriation of the cap-stones of Cromlechs for the sacrifice of human victims. This was, he thought, an idea pretty generally exploded, now that their sepulchral nature had been satisfactorily ascertained. The cap- stones having been always covered with a mound would also render this use of them impossible.

Mr. Cunnington agreed with Mr. Lukis as to the non- sacrificial nature of Cromlechs in general, and of Wayland Smith's Cave in particular. He also disputed Professor Donaldson's conclusions with reference to Boulders, and said there could be but little doubt that at a very remote period the whole of the chalk district of England was covered with sand. The action of the sea having removed the softer portions, the more solid masses were left scattered over the surface in the manner they were now seen.

Mr. Estcourt said some years ago he beard Professor Buckland give a familiar explanation of the origin of the stones. Dr. Thurnam also disputed some portions of the learned Professor's theory, sup- porting his view by reference to a ground-plan of the spot hitherto unpublished, which was made by Aubrey about the latter third of the 17th century. His remarks, as well as some further observations made by him, at the request of Sir John Awdry and other members, when the Cave was visited the next day, will be found in the following paper.