Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1866 V10 Pages 130-135

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1866 V10 Pages 130-135 is in Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1866 V10.

Examination of a Chambered Long Barrow [West Kennet Long Barrow [Map]], at West Kennet, Wiltshire. By John Thurnam (age 55).

One of the most remarkable chambered barrows of England is that at West Kennet, near the great stone circles of Avebury, which was explored for the Wilts Archæological and Natural History Society, in the summer of 1859, on the occasion of the Meeting at Marlborough.1.

Note 1. A more fully detailed account of this tumulus, will be found in the Archaeologia, vol. xxxviii., p. 405; where the notices of it by Aubrey, Stukeley, Sir Richard Hoare, Dean Merewether, and Mr. W. Long are given.

This long barrow has suffered much at the hands of the cultivators of the soil. Whilst the "Farmer Green" of Stukeley's days seems to have removed nearly all the stones which bounded its base, two being all which remain standing; later tenants, even in the present century, have stripped it of its verdant turf, cut a waggon-road through its centre, and dug for flints and chalk rubble in its sides, by which its form and proportions have been much injured. In spite of all this, however, the great old mound with its grey, time-stained stones, among which bushes of the blackthorn maintain a stunted growth—commanding as it does a view of Silbury Hill, and of a great part of the sacred site of Avebury—has still a charm in its wild solitude, disturbed only by the tinkling of the sheep-bell, or perhaps the cry of the hounds. Shade, too, is not wanting; for on the north side of the barrow, occupying the places once filled by the encircling upright stones, are, what are rarely seen on these downs, several ash and elm trees of from fifty to seventy years' growth. At the foot of the hill, half a mile away to the east, lies one of those long combs or valleys where the thickly scattered masses of hard silicious grit or sarsen stone, still simulate a flock of grey wethers," and which, as Aubrey says, "one might fancy to have been the scene where the giants fought with huge stones against the gods." From this valley there can be little doubt were derived the natural slab-like blocks, of which our "giant's chamber " and its appendages were formed.

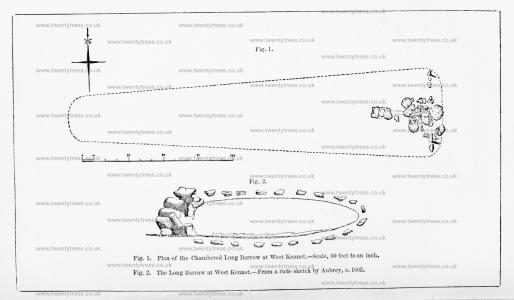

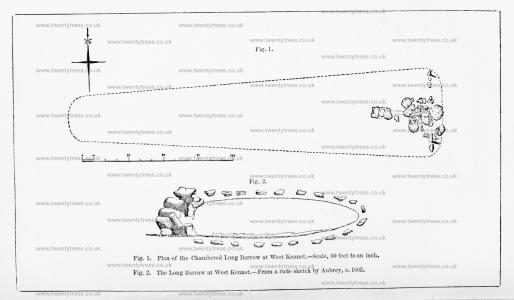

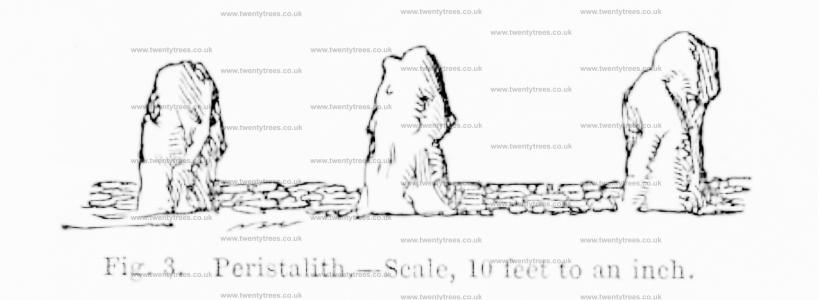

The tumulus, which is one of the longest known, measures 335 feet in length, 75 feet in width at the east end, and about 8 feet in greatest height. (Fig. 1.) It has been surrounded by a complete peristalith, which according to John Aubrey, was nearly perfect in the 17th century, but of which fragments only now remain. (Fig. 2.) Near both the north-east and south-east angles of the tumulus, two stones remain standing and there are two or three others which have fallen or been broken away, and are now partially buried in the turf. The entire barrow was no doubt originally surrounded with a ring of these stones, just as was the great chambered cairn of New Grange in Ireland [Map]. Some of the chambered long barrows of the west of England, as those of Stoney Littleton [Map] and Uley [Map], have been enclosed by a dry walling of stone in horizontal courses, carried to a height of from two to three feet. The surrounding wall of the long barrow at West Kennet, as is the case with similar tumuli in this district, united both methods, and was formed by a combination of ortholithic and horizontal masonry. This was ascertained by digging between the stones at the north-east angle of the tumulus. Here, at one spot, were several tile-like oolitic stones, the remains no doubt of a dry walling, by which the spaces between the sarsen ortholiths had been filled up, after the manner shown in the accompanying woodcut (fig. 3), though, carried probably to a greater height. In the long barrow on Walker Hill (Alton Down) [Map], near its east end, is an upright of sarsen, and below the turf at a little distance on each side, another fallen ortholith of the same stone was uncovered. Between these, on each side of the remaining upright, a horizontal walling of oolitic stones was found neatly faced on the outside, five or six courses of which remained undisturbed.

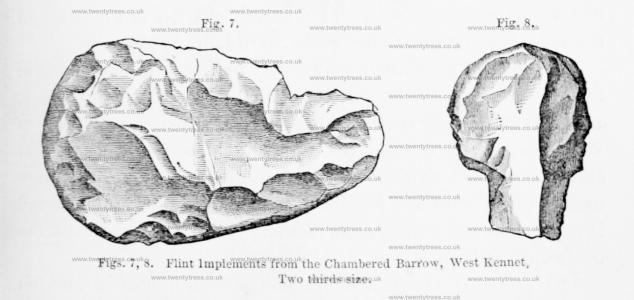

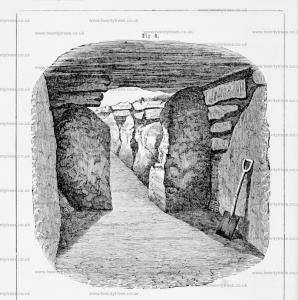

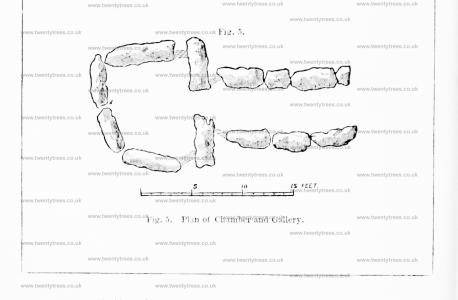

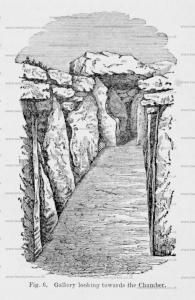

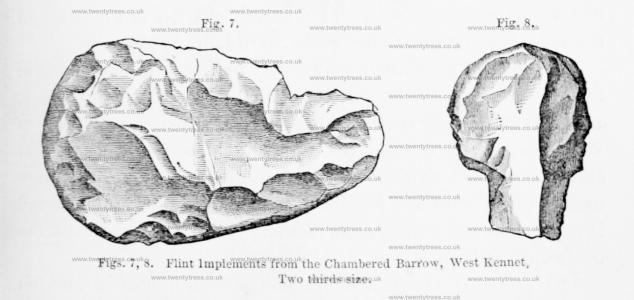

Permission had not been given to move any of the stones on the surface, and operations were confined to the neighbourhood of the presumed chamber, and to digging on the east and west sides of the three large cap-stones. Omitting the details of the excavation, it may suffce to state that the chamber was entered from the west end, and was found to be formed of six upright sarsen stones, covered by three very arge blocks of the same, and having a gallery entering it from the east, similarly constructed. (Figs. 4, 5, 6.) The chamber was about eight feet in length, by nine in breadth, and nearly eight feet in clear height. On clearing out the earth and chalk-rubble with which it was filled, the chamber was found to contain six skeletons, all, so far as could be made:out, in the crouched or sitting posture,—five being probably of males from 17 to 50 vears of age, and the sixth that of an infant. With one exception, they were of less than middle stature. Two of the skulls were remarkable for distinct traces of fractures, unequivo- cally inflicted before burial and probably before death. Bones of various animals used for food were found, including those of the sheep or goat, ox of a large size, roebuck, boars and other swine. There were very numerous flakes and knives of flint, some of which were circular and elaborately chipped at the edges: one only had been ground (fig. 7), and may have been used in flaying-animals. There were two or three large mallets or mullers of flint and sarsen stone, part of a rude bone pin, and a sin•gle hand-made bead of Kimmeridge shale. The fragments of coarse but ornamented pottery were remarkable for their number and variety (figs. 9, 10); and in three of the four angles of the chamber tuere was a pile of such, evidently deposited in a fragmentary state, there being scarcely more than two or three portions of the same vessel. One small vase had been perforated at the bottom and sides. (Fig. 11.) In the cen- tral part of the chamber was a shard of pottery, perhaps Roman, (fig. 12); and a fragment undoubtedly such, was turned up at some depth outside the chamber, near its western end,—affording a probable indication that it had been searched during the Roman period. By whomsoever opened, its contents had been but partially disturbed; as was proved by the condition and order of the skeletons, and by the presence of a defined layer of black unctuous earth immediately above them. Not a bit of burnt bone or other sign of cremation was met with; there were no traces of metal, either of bronze or iron; or of any arts for the practice of which a knowledge of metallurgy is essential.

The upright and covering stones, of which the chamber and its appendages were formed, were of the bard silicious grit or sarsen stone of the district; the horizontal maspnry (of which there were traces between the uprights at the bottom of the chamber and gallery, as well as surrounding the base of the mound), was of tile- like stones of calcareous grit, the nearest quarries of which are in the neighbourhood of Calne, about seven miles to the west.

The skulls, of which four were nearly perfect, are more or less of the lengthened oval form, with the occiput expanded and projecting, and present a strong contrast to skulls from the circular barrows of Wiltshire. They confirm the observation previously made, that crania from the long chambered tumuli of this part of Britain are usually of a narrow and peculiarly lengthened form. The forehead is mostly low and narrow; the face and jaws, as compared with the other ancient British type, decidedly small.

The principal skeleton, to which the skull figured in "Crania Britannica," (pl. 50) belonged, was that of a man about 35 years of age. It was deposited in the north-west angle of the chamber, with the legs flexed against the north wall. The thigh bone measured 17¾ inches, giving a probable stature of 5 feet 5 inches. The skull faced the west. The lower jaw was found about a foot nearer to the centre of the chamber, as if it had fallen from the cranium in the process of decay. Being imbedded in the clayey floor, the jaw was singularly well preserved, of an ivory whiteness and density, and even retained distinct traces of the natural oil or medulla. Near the skull was a curious implement of black flint— a sort of circular knife with a short projecting handle, the edges elaborately chipped. (Fig. 8.) The skeleton was perhaps that of a chief, for whose burial the chamber and tumulus were erected, and in honour of whom certain slaves and dependants were immolated.