Winterbourne Down Barrows

Winterbourne Down Barrows is in Station 5 Amesbury North.

Continuing our ride in an eastern direction over this rich down, we meet with a ditch and bank traversing it, and leading on each side directly into a British village. I have before started the new idea that these banks and ditches, of which there are so many in different parts of our county, were not boundaries, like Wansdyke, &c.1 but roads of communication from one village to another, in which the passenger could walk both sheltered, and almost unperceived: and here we have a convincing proof that this my supposition has solid grounds of support, for we find one of these ditches issuing from one village, and leading across the valley immediately into another; and as far as we could trace them, we perceive by the map, that the ditch and bank which are visible on Wilsford and Lake downs, pointed directly to these British villages, and still further northward we find another bank and ditch proceeding towards the great British village on Elston down. The general character of these towns is so similar, and their produce so uniform, that a repeated description of each of them would be tedious to my readers. Those on Stoke downs are interesting specimens, and the southern village presents a greater degree of regularity than usual: for in it we may trace the favourite square form of the Romans, which they almost universally adopted in the formation of their camps: the northern village bears a more decided British character.

Note 1. Whoever views these banks and ditches with an attentive and unprejudiced eye, will easily perceive a decided distinction between them, and those evidently formed for boundaries; the valla or the former being thrown up with a great deal of symmetry, and equally on both sides, with a wide and flat surface left between them at bottom; the latter having an elevated vallum on one side only, with a deep and narrow ditch on the other. Of these the districts comprehended within my work will afford striking examples in Wansdyke, North Wiltshire, and in Bokerley ditch, near Woodyates in Dorsetshire.

No. 3 [Map] is a long, or rather triangular barrow, standing nearly east and west, the broad end towards the former point; it measures 104 teet in length, 64 feet in width at the large end, 45 feet at the small end, and does not exceed three or four feet in elevation, This tumulus has been much mutilated, partly by former antiquaries, and partly by cowherds or shepherds, who had excavated the eastern end, by making huts for shelter. Our first section was made at the western end, but produced nothing. On making a second, we perceived the earth had been disturbed, and pursuing the section, found two or three fragments of burned bones. We next observed a rude conical pile of large flints, imbedded in a kind of mortar made of the martyr chalk dug near the spot. This rude pile was not more than four or five feet in the base, and about two feet high on the highest part, and was raised upon a floor, on which had been an intense fire, so as to make it red like brick. At first we conceived that this pile might have been raised over an interment, but after much labour in removing the greater part of it, we very unexpectedly found the remains of the Briton below, and were much astonished at seeing several pieces of burned bones intermixed with the great masses of mortar, a circumstance extremely curious, and so novel, that we know not how to decide upon the original intent of this barrow. The primary interment might have been disturbed before, or we might have missed the Britons might perhaps have burned the body by an intense fire on the spot, where the earth was made red; and the calcined bones might then have been collected together, and mixed in the mortar, which, with flints, formed the rude cone over the fire-place. If this opinion is right, the Britons in this case adopted a very singular method for preserving the dead. We have left some of the mortar containing the burned bones, near the top of the barrow, to satisfy the curiosity of any person who might wish to examine it. Though nearly the whole of the bones had slight tinge of green, we could not discover any articles of brass. On exploring this barrow further to the east, we found two deep cists containing an immense quantity of wood ashes, and large pieces of charred wood, but no other signs of interment.

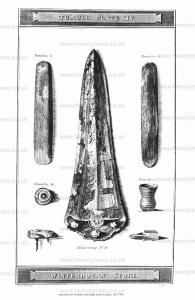

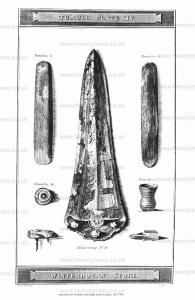

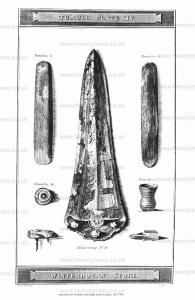

No. 5 [Map]. This large circular barrow is situated a few yards west of the road leading from Salisbury to Devizes, is flat at the top, five feet in elevation, and 110 feet in base diameter. When on the top of this tumulus, you perceive several depressions on the surface, from which, and its large dimensions, we conceived it must have been a family sepulchre, and so it proved to be. We opened it by a large square section near the centre, and in digging down to within a foot of the floor, we found the skeleton of a young person, deposited aver the north-west edge of a very large and deep oblong cist; and upon the same level, on the south side, we discovered an interment of burned bones. On clearing the earth to the depth of five feet, we reached the floor of the barrow, in which a cist of the depth of four feet was cut in the native chalk, and at the depth of two Feet on the southern side of the cist, was deposited the skeleton of an infant, apparently but a few months old. From the positions in which these interments were placed, it is evident they had been deposited at different times, and were subsequent to the primary one, in search of which we next proceeded. On clearing away the earth from the large cist, we found the head of a skeleton lying on the north side, but to our surprise, no vertebræ or ribs; further on were the thigh bones, legs, &c. At the feet was a little rude drinking cup, nearly perfect, and two pieces of a dark coloured slacy kind of stone, lying parallel with each other, which are engraved in Tumuli Plate XIV. We also found a large black cone, and an article like a pully, both of jet, and a piece of flint rudely chipped, as if intended for a dagger or spear. This tumulus, if more minutely examined, might very probably produce other interments, but from its great width, the operation would be attended with a very heavy expense.

No. 7 [Map] is a fine bell-shaped barrow, 122 feet in diameter, and 9 feet in elevation. After great labour in making a spacious excavation, we unfortunately missed the interment; but from finding the fragment of a very large urn, and a few burned bones, we have some reason to think the barrow might have been opened before.

No. 8 [Map]. This barrow, rather inclined to the bell shape, is 82 feet in diameter, and in elevation. It contained within a shallow oblong cist, the burned bones (as we conceived) of two persons piled together, but without arms or trinkets. In excavating the earth from this barrow, our men found a piece of square stone polished on one side, having two marks cut into it, also a whetstone.

No. 9 [Map], a small barrow not above sixteen inches in elevation, produced, six feet apart, the horns of two large stags, and between them a sepulchral urn inverted over a pile of burned bones. This urn is rudely made, yet elegant in its outline.1 On digging deeper, we discovered the skeleton of an adult lying with its head to the south; and on pursuing our researches to the depth of four feet in the native bed of chalk, we found another skeleton with its head placed towards the north; bat each of these interments was unaccompanied by any warlike or decorative articles.

Note 1. See Plate XVI.

No. 10 [Map]. In this small tumulus, which appears to have been partially opened before, found an oblong cist, which was arched over with the chalk that had been thrown out of it; and in the further part of it, a few fragments of burned bones, and a large glass bead, of the same imperfect vitrification as the pully beads so often before mentioned, and resembling also in matter, the little figures that are found with the mummies in Egypt, and are to be seen in the British Museum. This very curious bead has two circular lines of opaque sky blue and white, which seem to represent a serpent intwined round a centre, which is perforated. This was certainly one of the Glain Neidyr of the Britons, derived from glain, what is pure and holy, and neidyr, a snake. Under the word glain, Mr. Owen, in his Welsh Dictionary, has given the following article: "The main glain, transparent stones, or adder-stones, were worn by the different orders of the Bards, each having its appropriate colour. There is no certainty that they were worn from superstition originally; perhaps that was the circumstance which gave rise to it. Whatever might have been the cause, the notion of their rare virtues was universal in all places where the Bardic religion was taught. It may still be questioned whether they are the production of nature or art." Mr. Mason, the poet, thus alludes to these stones,

.... But tell me yet

From the grot of charms and spells,

Where our matron sister dwells,

Brennus, has thy holy hand

Safely brought the Druid wand,

And the potent adder-stone,

Gender'd fore th' autumnal moon?

When in undulating twine

The foaming snakes prolific join;

When they hiss, and when they bear

Their wond'rous egg aloof in air;

Thence, before to earth it fall,

The Druid in his holy pall,

Receives the prize,

And instant flies,

Follow 'd by the envenom'd brood,

Till he cross the silver flood.

The serpent has ever been respected by the nations of antiquity, and noticed with peculiar marks of veneration. It was considered as an emblem of immortality, and from the circumstance of shedding its skin annually, a symbol of renovation. We find it introduced on the coins and altars of the ancients, and even temples, from their resemblance in form, assumed the title Of Dracontia. Of these, we have a singular example in our own county, at Abury in North Wiltshire, which 1 shall describe minutely during the progress of my work.

The beads or rings, which are the present object of my attention, are thus noticed by Bishop Gibson, in his improved edition of Camden's Britannia: "In most parts of Wales, and throughout all Scotland, and in Cornwall, we find it a common opinion of the vulgar, that about Midsummer Eve (though in the time they do not all agree) it is usual for snakes to meet in companies, and that by joining heads together, and hissing, a kind of bubble is formed like a ring about the head of one of them, which the rest by continual hissing, blow on till it comes off at the tail: and then it immediately hardens, and resembles a glass ring; which whoever finds, (as some old women and children are persuaded) shall prosper in all his undertakings. The rings which they suppose to be thus generated, are called Gleinneu Nadroedh, i. e, Gemmæ Anguinum, whereof I have seen at several places about twenty or thirty. They are small glass annulets, commonly about half as wide as our finger rings, but much thicker; of a green colour usually, though some of them are blue, and others I have also seen two or three curiously waved with blue, red, and white, earthen rings of this kind, but glazed with blue, and adorned with transverse streaks or furrows on the outside. There seems to be some connection between the GLAIN NEIDYR of the Britons, and the OVUM ANGUINUM mentioned by Pliny, as being held in veneration by the Druids of Gaul; and to the formation of which, he gives nearly the same origin. They were probably worn as an insigne, or mark of distinction, and suspended round the neck, as the perforation is not suffciently large to admit the finger. This bead, which I consider as a very interesting relict of antiquity, is engraved of its original size in TUMULI Plate X IV.