Biography of Thomas Seddon 1821-1856

Thomas Seddon 1821-1856 is in Painters.

On 28 Aug 1821 Thomas Seddon was born to Tom Seddon.

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1851. 13 Nov 1851. After Clipstone Street spent the evening with Wells (age 22) at [his brother] John (age 24) and Thomas Seddon's (age 30), 7 Percy Street; G. Rossetti (age 23), F. M. Brown (age 30) and G. Truefitt (age 27) were there.

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1852. 03 Mar 1852. Tom Seddon (age 30) showed me the drawing by G. Rossetti (age 23) he spoke to me about? I was so pleased with it that I decided on having it at once. Some very fine colour about it independent of its other merits. I am to give 5 gns. for it.

1853-1854. Thomas Seddon (age 31). "View on the Nile".

1853-1854. Thomas Seddon (age 31). "View on the Nile".

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1853. 26 Jan 1853. January 26. Tom Seddon (age 31) called on me and said he and Gabriel Rossetti (age 24) had been speaking about me and thinking it would be good for me to try painting in oil.

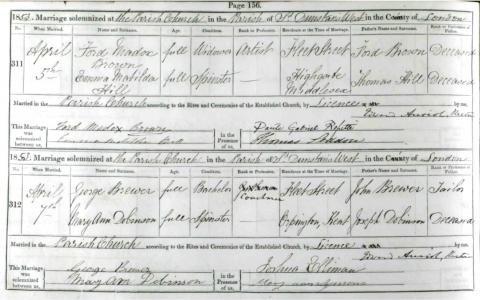

On 05 Apr 1853 Ford Madox Brown (age 31) and Emma Matilda Hill (age 23) were married at St Dunstan's in the West, Fleet Street [Map]. The witnesses were Dante Gabriel Rossetti (age 24) and Thomas Seddon (age 31). The Rector who performed the ceremony was Edward Auriol (age 48).

Edward Auriol: On 27 Feb 1805 he was born to James Peter Auriol. In or before 1841 he was appointed Rector of St Dunstan's in the West, Fleet Street. In or before 1841 Edward Auriol and Georgina Morris. On 10 Jul 1880 Edward Auriol died.

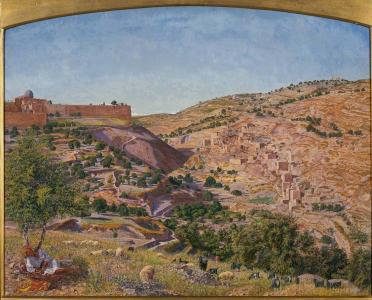

1854-1855. Thomas Seddon (age 32). "Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel".

1854-1855. Thomas Seddon (age 32). "Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel".

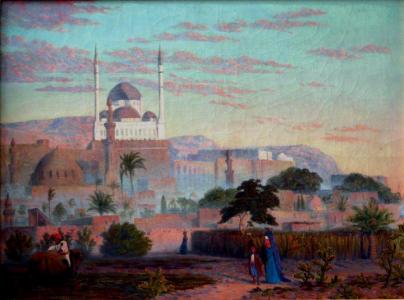

1856. Thomas Seddon (age 34). "The Citadel of Cairo".

1856. Thomas Seddon (age 34). "The Citadel of Cairo".

On 23 Nov 1856 Thomas Seddon (age 35) died of dysentery at Cairo, Egypt.

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1855-1857. 09 Feb 1857. Brighton, February 9, 1857.

My Dear Allingham,

At the very time you were writing to me "How happy you travellers are, How I envy you !" your humble servant was lying on his bed at Giornico suffering the consequences of an innocent bit of fun, namely, scrambling over a wall and giving chase to a trio of country lasses who were wont to come and sit by me as I worked, and sing quaint ditties of the country to me. In the excitement of the moment I quite forgot my first nine months lying up some 5 or 6 years ago from an injury to the same part (the hip joint) by overwalking and skating, or should not at this very time be still paying the penalty of my folly. For, in fact, after resting and breaking off my work at Giornico and following professional advice in Paris for a month without benefit, I have at length been obliged to come down to this miserable place, accompanied by my sister as nurse, and put myself under my old doctor, Harrap (a quack as the faculty chooses to call him) who so wonderfully set me on my legs the first time. You will easily conceive what a sore trial this is to me, fond as I am of independence and freedom of movement. For in addition to lameness, comparative helplessness and expense, there's the thought of my lost season and the work neglected and neglecting to harass me. For five months I've scarcely touched a brush or pencil, and it's impossible to say when I shall be able to take to either vigorously again. All is not, you see, coulear de rose with us artist ramblers. There's poor Seddon, whom we have lost altogether, dying away from his wife and relatives in Cairo; and young Herbert; a painter of promise, cut off in the Auvergne. I hope in the meanwhile you have been blessed with good health and spirits, and that these have found vent occasionally in song of your own genuine quiet stamp. The "mowers" came very acceptably, and set the sharp scythe swiftly sweeping in my mind's ear and eve.

I should like you to have seen the chestnut harvest, and, especially, the vintage, at Giornico. The vines are not those ugly, short, stiff, monotonous things tied to sticks, that one meets with in France or by the Rhine, but free and full and forming a canopy of green and purple at a man's height from the ground, extending often many acres without interruption. You may in some measure conceive the effect of such a vineyard in vivid sunlight, the leaves and fruit glowing greeny-gold and crimson with transmitted light, tempered by the grey bloom and white lustre of their upper surfaces, and the network of flickering light and shadow on the supports and grass beneath; and then, giving wonderful life to the picture, the varied groups of vintagers from the hills and villages about, with their blue skirts and white shirt sleeves tucked up, their heads covered with scarlet and many-coloured fichus upturned, and their bare arms and hands, wine-stained, uplifted picking the purple pendants in the golden chequered light and flood of warm autumnal air. In fine contrast to this were the same vineyards looked at from above, at the commencement of a storm, when the big, heavy drops, heard afar off in their coming, began pattering loud upon the floor of leaves extending almost across the valley, and the fitful gusts of wind swooping over this green pavement came bristling it into hurrying spaces of shivering grey. Of course there was no painting either the oneor the other, even had I been in the cue. I passed the Simplon as late as the 8th November (though lingering at Giornico in hope of convalescence) the day before the snow.

The valley of Domo d'Ossola, as we entered it from the Maggiore lake by a deeply coloured sunset was magnificent. The groups of red-lit peaks seemed to be literally playing like flame along the green and profoundly quiet sky into which they almost melted. The glowing sunset gave gradual place as we approached the summit of the pass to misty moonlight which added mystery and awe to sublimity and loveliness. As the grey and bitterly cold dawn broke, we were passing through a dreary region of peaked granite snow and ice; and then gradually stole into view the colossal range of the Bernese Oberland with the glaciers at its roots stretching away inexpressibly grand and desolate till lost in the falling snow, mist or drizzle, which rendered all its forms doubly huge and ghostly. Then at Briegg commenced the wonderful valley of the Rhone, in which is the picturesque and characteristic town of Sion-N'lartigny, where I stayed a night.

With the gorge of the Trient, with the Lake of Geneva studded as it is—or rather as its banks are—with white houses and hotels ; and seeing it as I did in so late and dreary a season with the higher mountains cloud covered; I was much disappointed. Equally so with Chillon, Vevey, Clarens and Geneva themselves. Lausanne, I thought, was the only place on the northern bank I would care at all to stay at.

Between Seyssel and Lyons I noted in the grey twilight glimmer some very unusual interesting scenery. Long narrow treeless defiles with continuous jutting beds or string courses of rock along the sides with sloping debris at the bottom, room enough only for the road and small lakes here and there. Would you believe it, a railway embankment was being jammed into this ravine and smack through the little lakes, which will in consequence be nearly choked up, and the whole scene ruined, to a painter's eye at least. It's for you poets to "point the moral" and show us what we gain by all this—that's to say wishing to get over the ground so fast. I believe, but can't see, that all's working for good.

Your references to Tennyson and Browning were very interesting. What wonderful things there are in "Nlen and Women' '—especially ' 'In a Year," "Fra Lippo Lippi," that letter from the Arab student, and "Blougram." What I've read of "Aurora Leigh" I don't like nearly as much as these.

I didn't meet Ruskin (age 38) abroad. By a letter just received from my friend Warren, I find he (Ruskin) was present at the meeting at Hunt's about poor Seddon's works and spoke very feelingly and sympathisingly.

Rossetti (age 28), I hear, is hard at work on the Tennyson illustrations. I know nothing of what the rest of the brotherhood are doing.

I am very glad that "Anstis Cove" continues to please. It is so much more than I dare to hope for my drawings in general. I am anxious to know—as you don't refer to it—that you found the little spring sketch I promised you of a favourite valley in N. Wales, when you opened the case containing the larger drawing. Although slight, and done in 2 or 3 hours I think it's as truthful, as far as it goes, as the other, and that you would get to like it also. It was done on the spot. I put it loose into the case.

It's time I brought this jobation to a close. I shall be glad of a few lines when you can manage it.

Yours very truly,

George P. Boyce.