Bronze Dagger

Bronze Dagger is in Bronze Age Artefacts.

600BC. Date unclear. Boddington Hill Fort, Buckinghamshire [Map]. A slight Univallate Hill Fort on the summit of Boddington Hill

Historic England 1011304:

The monument includes a univallate hillfort occupying the summit of a steep sided chalk spur. The hillfort is oval in shape, measuring overall some 500m long by 220m wide, and has an internal area of some 6ha. It lies with its long axis along the hilltop orientated north-east to south-west. The defences run roughly around the 240m contour and comprise a single rampart and outer ditch. The defences are strongest around the south and east where the outer ditch is up to 1.6m deep and the outer scarp of the rampart up to 3.4m above the ditch bottom on its outer side and 1.7m high on its inner side. In places along this south-east side there are the remains of an outer or counterscarp bank which runs along the edge of the ditch; this averages 5m wide and 0.4m high. The defences become confused towards the north-east end of the hillfort as the result of later quarrying but their course can still be followed except where they have been destroyed in the northern corner of the enclosure. This position is almost certainly the site of the original hillfort entrance but today nothing of this can be recognised. This northern part has suffered considerable disturbance from occupation of the site by Calloway or Peacock Farm which stood in this vicinity until its demolition in the 1950s. Surface irregularities, along with tile and brick waste scattered on the surface here, relate to this phase of occupation. Around the north-western side of the hillfort the outer ditch has been overlain by a modern terraced forestry track. However the main rampart survives as a single well defined scarp averaging 2.6m high. Some 200m south along its length the rampart becomes stronger rising to an average height of 3.6m and an inner bank once more becomes recognisable, averaging 0.6m high. A modern entrance gap 5m wide has been cut through the rampart some 30m south of the commencement of this inner bank. The last 120m of this length of the rampart has an inner ditch 5m wide and 0.8m deep which probably served as the quarry for the inner bank. The outer ditch remains buried beneath the modern forestry track throughout the complete length of this western side. At the extreme south-western corner of the hillfort the outer rampart is lowered to form an entrance ramp which could be a second original approach to the interior of the fort. There is no outer ditch at this position, the ditch commencing some 40m to the east. Whether the ditch was originally intended to end short of this ramp or whether it has been subsequently infilled is unclear. The interior of the hillfort is today heavily afforested. Finds from the interior of the fort have in the past included fragments of Iron Age pottery, an ingot, part of a bronze dagger, a flint scraper and a spindle whorl. A section excavated through the rampart in the area of the southern entrance revealed fragments of pottery indicating occupation of the site during the 1st-2nd centuries BC. A series of lesser modern banks associated with the modern farm enclosure can be identified running inside and parallel to the prehistoric earthworks. A large circular concrete reservoir 33m in diameter lies approximately central to the site. The concrete reservoir, along with all modern boundary features, structures and metalled surfaces are excluded from the scheduling, although the ground beneath these is included.

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 12th of May, 1845, was opened a very large cairn, or stony barrow, called Brier Lowe [Map], near Buxton; it was about six feet in central elevation, and about twenty yards in diameter. On approaching the centre, upon the level of the natural surface, it was found to be covered with rats' bones, amongst which were some small pieces of an urn, and some burnt human bones, which had doubtless been disturbed upon the occasion of the interment of a body, which was discovered in the middle of the barrow. This skeleton was laid upon some flat limestones, placed on the natural ground, with its head towards the south, and its knees contracted; it was very large and strong, and was accompanied by a bronze dagger, in excellent preservation, with three rivets remaining which had attached the handle: this fine instrument lay close to the middle of the left upper arm, and is the first of the kind ever found in Derbyshire. The skeleton was surrounded with a multitude of rats' bones, the remains of animals which had in former times feasted upon the carcass of the defunct warrior, which fact was satisfactorily proved by the gnawed appearance of the various bones, and from the circumstance of several of the smaller ones having been dragged under the large flat stones upon which the body lay, and which could not by any other means have got into that situation. This barrow is extremely interesting, as having produced conclusive evidence regarding the "quæstio vexata" of the cause of the perpetual occurrence of rats' bones in barrows in various places, which are the remains of generations of those unpleasant quadrupeds which have burrowed into the tumuli, in all probability to devour the bodies therein interred.

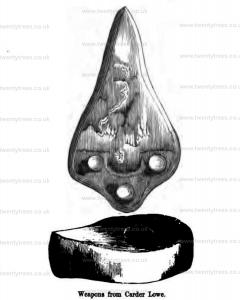

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 21st of May, 1845, was opened a barrow called Carder Lowe [Map], near Hartington, which is about fourteen yards in diameter, and, owing to the former removal of its summit, is not more than two feet in average elevation. In the process of excavation about eighty quartz pebbles and several instruments of flint were found, amongst the latter a very neatly-formed barbed arrow-head. These articles were possibly cast into the mound during its construction by mourners and friends of the deceased, as tokens of respect. In addition to these were a few pieces of a coarse urn, curiously ornamented.

About the centre was found the skeleton of the chiefs over whom the barrow had been at first raised. He lay upon the right side, with the head towards the east, and the legs contracted very slightly; at his elbow lay a splendid brass or bronze dagger, in a good state of preservation. It has three large rivets remaining, which had securely attached the handle, which was still easily traceable by the wood of which it had been composed having decayed into a black mould, which contrasted strongly with the light-coloured, clayey soil in which the body was imbedded. A few inches lower down was placed a beautiful axe- or hammer-head of light-coloured basalt of much smaller size than usual, and which was originally nicely polished. Close to the head was found a small piece of calcined flint, of no apparent design or form. The skeleton was surrounded with rats' bones, the undoubted remains of those four-footed cannibals who had preyed upon the body, and had endeavoured to devour the bones of this ancient British chief, many of the latter were half-eaten away. Rather nearer to the south side of the barrow, and on a higher level, another interment was discovered, which consisted of a skeleton of mighty size, the femur or thigh-bone measuring twenty-three inches in length, which would give a height to the owner, when alive, of six feet, eight or ten inches. Along with this lengthy individual, an iron knife and three hones of sandstone were deposited; also a few pieces of calcined bone. This was evidently a secondary interment, of later date than the one previously described, which was undoubtedly the original one.

Note. The bronze dagger on display at Weston Park Museum, Sheffield.

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the afternoon of the same day, a barrow [Map] at New Inns was opened; it is situated upon a ridge of high ground immediately overlooking the secluded hamlet of Alsop-in-the-Dale [Map]. The centre of the tumulus being reached, the original interment was discovered lying upon the rocky floor, upon its left side, with the knees contracted, and the face towards the south, without being inclosed in any kind of cist or vault; close to the back of the head was a beautiful brass dagger of the usual form, but with smaller rivets than common, which the appearance of the surrounding mould denoted to have been buried in a wooden sheath; about the knees two small brass rivets were found entirely unconnected, and as on a strict scrutiny nothing else was discovered, it is most probable that they had riveted some article of perishable material, wood for instance which had so completely decayed as to leave no trace. In the course of this excavation were found part of another haman skeleton, some animal teeth, and two instruments of flint, which had all been previously disturbed.

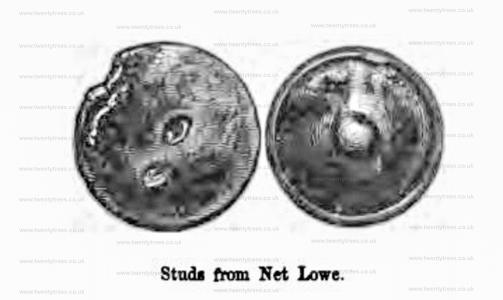

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 4th of June, 1845, another large flat barrow was opened, which is situated upon the level summit of a hill upon Alsop Moor, known by the name of Net Lowe Hill [Map]. This barrow is about twenty-five yards in diameter, and not more than two feet in height; it was opened by cutting through it in different directions, so as to divide it into quarters. In each of these trenches, on approaching the centre, were found horses' teeth and an abundance of rats' bones; and in one of them a small piece of a coarse urn. In the centre of the tumulus was found a skeleton extended on its back at full length, and lying on a rather higher level than the surface of the natural soil; close to the right arm lay a large dagger of brass (broken in two by the weight of the superincumbent stones), with the decorations of its handle consisting of thirty rivets, and two pins of brass. In vol. i, plate 23, of Sir Richard Hoare's "Ancient Wiltshire" a dagger is engraved of a precisely similar character the number of rivets or studs and pins being exactly the same; close to this dagger were two highly-polished ornaments made from a kind of bituminous shale known in the south of England as Kimmeridge coal and equally well known to the archaeologist as the material of the coal money and of many other ancient British ornaments. Those in question are circular and moulded round the edges having a round elevation on the fronts to allow of two perforations which meet in an oblique direction on the back for the purpose of attaching the ornaments to some part of the dress or more probably to the dagger-belt of the chief with whose remains they were interred. In vol. 1, plate 34, of Sir Richard Hoare's book a similar ornament of jet is engraved, which is smaller, and does seem to have a moulding round the edge. It is a singular fact that, although the skeleton had evidently been never previously disturbed, the lower jaw lay at the feet of the body. Along with the above-mentioned articles were numerous fragments of calcined flint, and amongst the soil of the barrow were two rude instruments of the same.

Thomas Bateman 1846. On the 15th of August 1846, another barrow [Bole Hill Barrow [Map]], on higher ground, a little farther on the opposite side of the road to Buxton, was opened. Its diameter is greater than that of the last, but, like it, is surrounded by a circle of very large stones. In the centre was an erection of very large flat stones, regularly walled in courses, and having for its base a piece of rock four feet by five, and one foot thick, approaching to a ton weight, so that if the earthy part of this barrow had been carefully removed so as to leave these stones undisturbed, there would, according to the old school of antiquarianism, have been a complete druidical circle, with a cromlech or altar for human sacrifices standing in the centre; more particularly, as the flat stone at the top of the central pile had a considerable inclination towards one side, which peculiarity in similar structures has been gravely accounted for as an intentional provision to carry off the blood of the unfortunate victims now and then sacrificed by the Druids. But to return to the funereal discoveries made in this barrow; on removing the aforesaid large stone, a few pieces of an unusually coarse urn, some calcined human bones, and the remains of a host of rats, with here and there a skull of the weasel, appeared; though level with the surrounding field, the earth under the stone was loose, and had been removed to form a cist, 'which had for its floor a level surface of rock, some three feet below the natural soil, and which was neatly walled round with flat stones; in this grave was a skeleton of large dimensions, lying on its left side, in a contracted posture; behind the head was a brass dagger of the usual type, measuring six inches and a quarter in length, and in the highest preservation; it has the appearance of having been silvered, and still retains a brilliant polish; when deposited it had been inclosed in a wooden sheath, the remains of which were very perceptible at the time of its discovery. Near it were two instruments of flint, and two more were found during the progress of the examination of the tumulus.

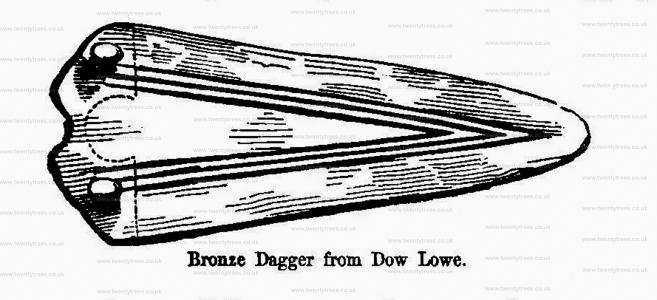

Thomas Bateman 1846. On the 5th of September, 1846, was examined the lower part of a large barrow (called Dowe Lowe) [Note. Dow Low Barrow [Map]] near Church Sterndale; the upper part of which had been some time removed, on which occasion an urn and other antiquities were found; fortunately the primary interment was left untouched; though the remnants of later interments deposited on a higher level, consisting of sundry pieces of bone, burnt and unburnt, fragments of urns, and a small piece of thin cylindrical brass, testified to the havock that had been made. The most remote interment consisted of two much decayed skeletons, lying near each other upon the floor of the barrow, about two yards from the centre; one was accompanied by a fluted brass dagger, placed near the upper bone of the arm, and an amulet or ornament of iron ore, with a large flint instrument, which had seen a good deal of service, lying near the pelvis. A few chippings of flint and calcined ];|Luman bones were distributed near the two skeletons.

Kenslow Barrow. February 3rd. - The excavation of the grave cut in the rock, which contained the previously discovered interments, was commenced: the rubbish being cleared out, we found some portions of the skeleton which had evidently lain undisturbed; with them was a small and neat bronze dagger, 3 inches long, with the three rivets by which the handle was attached, remaining. A little above these we found an iron knife of the shape and size usually deposited with Anglo-Saxon interments, which had most likely been thrown in unobserved when the grave was refilled in 1821. About the same place was a bone pin with a perforated head. By digging in the outer parts of the barrow, another bone crescent and several good instruments of flint were found.

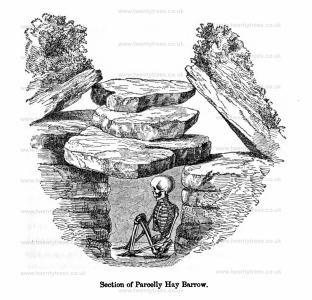

Parsley Hay. March 6th was passed in opening a cairn or tumulus [Map] [Parsley Hay Barrow [Map]] of stone in a plantation near the Parcelly Hay wharf of the Cromford and High Peak Railway. We found the primary interment beneath the middle of the barrow, in a small oval excavation in the rook below the natural surface of the land, about three feet in depth, and not exceeding the same in its greatest diameter, consequently the body had been placed upright in a sitting or crouching posture, as was abundantly evident from the order in which the bones were found. The grave was roughly covered in with large flat slabs of limestone, which had prevented the material of the tumulus from quite filling it up; a good deal of earth had, however, been washed in, which had the effect of preserving the bones in unusual perfection. The remains accompanying the body were of the poorest description, consisting merely of three pieces of chipped flint, some shreds from a drinking cup, and various animal bones and teeth, some of which were calcined. The fine skull from this interment has been engraved in the magnificent work by Messrs. Davis and Thumam, entitled "Crania Britannica," where its internal capacity is given at 72½ ounces; length of the femur, 18.3 inches. The high antiquity of this interment may be inferred when we take into consideration the fact, that upon the covering stones there lay another skeleton, quite unprotected from the loose stone of the barrow, and accompanied by weapons indicating that the owner lived at a very remote period. This body was badly preserved, owing to the percolation of water through the over lying stones, but it appeared to have been laid as usual upon the lefl side, with the knees slightly advanced; near the upper part of the person were placed a very elegantly formed axe head of granite, with a hole for the shaft, and a very fine bronze dagger of the earliest or archaic bronze period, with three studs for fastening the handle. The engraving gives an accurate section of this remarkable barrow,

Mare Hill. May 25th, we opened a barrow [Mere Hill Barrow [Map]] on the top of Mare Hill; near Throwley Hall, by sinking by the side of a mass of natural rock which approached the surface near the middle of the tumulus. About three feet down we discovered a grave, cut in the rock, covered, more especially about the sides, with charcoal: in it were two skeletons, near the shoulders of one was a spear point of calcined flint; in the earth, near the grave, were found a small piece of pottery and a piece of lead, having the appearance of wire, which subsequent researches prove to have been accidentally fused from metalliferous gravel present upon the spot where either a corpse was burnt or an urn baked, which was generally the site afterwards occupied by the tumulus.

Carrying the excavation to the further side of the before-named rock, we found that the artificial ground extended much deeper, and was mingled with fragments of human skeletons and rats' bones; and about four feet from the surface was a cist of flat stones placed on end, which contained three interments on different levels: the uppermost was the skeleton of a child, the next a deposit of burnt bones, among which were some animal teeth; the lowest was an entire skeleton. Immediately above the burnt bones was found a small bronze dagger about 3 inches long, perforated at the lower end with two holes, which did not present the usual rivets for attaching the handle, and which must therefore have been secured by ligatures. Outside this cist were found, pieces of human skull, sherds of pottery, flints, animal bones, and a piece of lead of conical shape.

Note A. this point we continued the excavation at right angles, being induced to do so by observing another declination in the earth, which led to another deposit of calcined bones. Further on at the depth of about two feet from the surface, was the skeleton of a child, laid as usual on the left side, with the knees drawn up, in a state of decay, accompanied by a very neatly ornamented vase 5 inches high, which was placed by the side of a flat stone set on edge for its protection. Half a yard further we found another incinerated interment, the bones, amongst which were a good arrow head of flint and a perforated bone pin, having been placed within a small inverted urn much decayed, which lay in the midst of a heap of burnt earth and charcoal. Near the same place were a piece of fused lead and the skeleton of a child, without any relics.

Shuttlestone near Parwich. On the 3rd of June we examined a mutilated barrow in a plantation upon Parwich Moor, called Shuttlestone [Map], which had originally been about four feet in height; it consisted of a compact mass of tempered earth down to the natural surface of the land, below which point, in the centre of the barrow there appeared a large collection of immense limestones, the two uppermost being placed on edge and all below being laid flat, though without any other order or design than was sufficient to prevent the lowest course resting upon the floor of the grave, inside which they were piled up, and which was cut out to the depth of at least eight feet below the natural surface; thus rendering the total depth from the top of the mound to the floor of the grave not less than twelve feet. Underneath the large stones lay the the skeleton of a man in the prime of life and of fine proportions, apparently the sole occupant of the mound, who had been interred whilst enveloped in a skin, of dark red colour, the hairy surface of which had left many traces both upon the surrounding earth and upon the verdigris or patina coating a bronze axe-shaped celt and dagger, deposited with the skeleton. On the former weapon there are also beautifully distinct impressions of fern leaves, handsful of which, in a compressed and half-decayed state, surrounded the bones from head to foot. From these leaves being discernible on one side of the celt only, "whilst the other side presents traces of leather alone, it is certain that the leaves were placed first as a couch for the reception of the corpse with its accompaniments, and after these had been deposited, were then further added in quantity sufficient to protect the body from the earth. The position of the weapons with respect to the body was well ascertained; and is further evidenced by the bronze having imparted a vivid tinge of green to the bones where in contact with them. Close to the head were one small black bead of jet and a circular flint; in contact with the left upper arm lay a bronze dagger with a very sharp edge, having two rivets for the attachment of the handle, which was of horn, the impression of the grain of that substance being quite distinct around the studs. About the middle of the left thigh bone was placed the bronze celt, which is of the plainest axe-shaped type. The cutting edge was turned towards the upper part of the person, and the instrument itself has been inserted vertically into a wooden handle by being driven in for about two inches at the narrow end - at least the grain of the wood runs in the same direction as the longest dimension of the celt, a fact not unworthy of the notice of any inclined to explain the precise manner of mounting these curious implements. The skull, which is decayed on the left side, from the body having lain with that side down, is of the platy-cephalic form, with prominent parietal tubers - the femur measures 18½ inches.

Deepdale. June 19th, we opened another barrow at Deepdale, in the immediate vicinity of the others. The field in which it is situated is called Burnet's Low, the prefix being derived from a late occupier of the land. The mound was 17 yards across, and having no great elevation it promised an easy task; but having dug to the depth of two feet, we arrived at the side of a very large grave, about six feet wide, cut at least three feet deep in the rock; it was filled with stones without any earth, except what had been washed in during the lapse of ages. We cleared it out for the distance of ten feet from the southern end, without meeting with the other extremity, which time would not allow of our doing. The sides were cut down perpendicularly, and were blackened by charcoal. On the west side within the grave, was a skeleton, deposited on the left side with the head to the south, and the knees drawn up; under the shoulders of which was a well preserved bronze dagger, with three rivets for the purpose of fastening the semilunar handle, which had imparted a green tint to the bones with which it had been in contact. The earth above was mixed with pebbles and bouldered pieces of sandstone, and in it we found an arrow point of flint

End Low. On the 13th of July we re-opened the large barrow at End Low [Map], which was first attempted in 1843, without our finding the primary interment. Our researches this time resulted in the discovery of the remains of the original occupant, which were, after the expenditure of much labour, found in a cist cut down in the rock to the depth of six feet beneath the natural surface, and upwards of ten feet from the top of the barrow. The skeleton was that of a finely proportioned man, rather above the middle size, and was in good preservation, with the exception of the head, which was decayed at the left side, from contact with the floor of the grave. The bones lay apparently without much regularity, which was attribute able to the settling down of the stones upon the body during the process of decay. At a small distance from them was a bronze dagger and spear head of flint, of a grey colour. The grave was bounded on three sides by rock, and the remaining one was walled up to a level with them with loose limestones. The skull is engraved in the Crania Britannica, and is described by the learned writer as "a well-formed head, presenting very clearly the conformation of the true ancient British cranium, of which it may be regarded as belonging to the typical scries." The femur measures 18.8 inches.

Calton Moor. July I3th, a tumulus on Calton Moor, called Thorncliff; about a mile from the village of Calton, was opened. It is a large bowl-shaped barrow, 26 yards diameter, considerably elevated in the middle. We commenced a section four feet wide through the centre, cutting first through a mixture of earth and small stones, in which lay a very slender skeleton, measuring 5 feet 6 inches in length, which had been deposited at fnll length on its right side, about four feet east of the centre of the barrow, and not more than a foot beneath the turf, probably an interment of much later date than the barrow itself; we next encountered a stratum of clay 4 feet thick, below which were loose stones, then small stones mixed with clay down to the natural surface, where we found a rock grave extending under the east side of the moimd, which was cleared out to the depth of three feet without our arriving at the bottom. Being now four yards from the summit, at an advanced hour in the day, we attempted to reach the floor of the grave by undermining the stratum of clay forming an arch over the grave, but having undercut it to the extent of six feet, we very fortunately abandoned the work as unsafe shortly before it fell in, and terminated both the day's labour and the chance of discovering the original interment. Animal bones and pieces of flint were found below the clay. Although the arrangement of this volume is chronological, we may be allowed to deviate from it in this instance, for the sake of finishing the account of the contents of the grave; which were discovered on the 29th and 30th of August, when the direction of the grave being known, we sunk down upon it, and after working upwards of a day and a half, had the satisfaction of finding, at a depth of more than four yards from the surface, the primary deposit in this difficult barrow; namely, the remains of a large skeleton, accompanied bu a neat instrument of flint and a bronze dagger, with three rivets of the usual form, but broken, perhaps by the pressure of some very large stones with which the grave was filled, and in consequence of which our labours were rendered much more arduous.

Readon Hill. September 4th, opened a barrow nineteen yards diameter and three feet high, on Readon Hill [Possibly Wredon Hill Barrow [Map]], near Ramshorn, which is mentioned by Plot, Hist. Staff, fol. 1686, p. 404. It contained two skeletons extended at length, about the centre, without any protection from the earth of which the mound was formed, with the exception of a few stones in contact with one of the bodies, which was possibly interred at a subsequent period to the other, as it was not more than two feet from the surface of the barrow, whilst the other lay on the natural level, at least three feet from the turf covering the mound. Vestiges of the hair of the former were perceptible about the skull, which was that of a young man, and in perfect preservation; and a small pebble was found at the right hand (compare Barrow [Map] opened 30th May, 1845, Vestiges, p. 67). The other, and probably earlier interment, was covered with a thin layer of charcoal. The skull is that of a middle-aged man, the vertex much elevated, the left side completely decayed from lying in contact with the floor of the barrow. At some distance from either of the skeletons, but nearest to the higher interment, from which, however, they were full two yards, lay an iron spear, thirteen inches long, with part of the shaft remaining in the socket, and a narrow iron knife, eight inches in length. An examination of these by the microscope, enables us to add the further information that the spear has been mounted on an ashen shaft, about one inch of which yet remains, owing its preservation to being saturated by the ferruginous matter produced by the decomposition of the iron - outside the iron are numerous casts of grassy fibre, and the larvae of insects, apparently flies - the grass must have been present at the time of interment in considerable quantity. The knife shews fewer traces of the vegetable, and more of the animal structures, the tang where inserted into the handle, shews the impression of horn. It is fortunate that metals in a state of oxydization have the property of taking, and retaining, the most delicate casts of substances the most perishable with which they lie in contact; we thus gain much valuable information as to the materials of dress in times of pre-historic antiquity, and are enabled to describe the circumstances under which the dead were committed to the grave, with an exactitude resulting from a strictly inductive method of reasoning. For example, we find that the early Celtic population, whose chief men were armed with the bronze celt and dagger, not only wore the skins of animals during life, but were enveloped in the same after death, and were thus laid upon a bed of moss or fern, before being buried out of the sight of their friends beneath the sepulchral mound. In later times, when the use of iron became so general as to supersede the more ancient metal bronze, we find a corresponding advancement in the materials of clothing, the impression of woven fabrics, of varying degrees of fineness, being almost invariably distinguishable on the rust of weapons found in the barrows; although the old custom of providing a grassy couch for the remains of the deceased was still retained, from an intuitive feeling beautifully expressed by Sir Thomas Browne, in his Hydriotaphia, when referring to the sepulture of the ancients, he writes - "that they have wished their bones might lie soft, and the earth be light upon them. Even such as hope to rise again would not be content with central interment, or so desperately to place their reliques as to be beyond discovery, and in no way to be seen again; which happy contrivance hath made communication with our forefathers, and left unto our view some parts which they never beheld themselves."

On the following day we examined another barrow in the same neighbourhood, about 21 yards diameter. It is called Wardlow, and is constructed over a lump of rock, in the middle of which was cut a grave, which we found had been previously disturbed, it had originally contained a skeleton with burnt bones, and chippings of flint. A cutting through the side of the mound where there was the greatest accumulation of factitious earth, produced many fragments of human bone, together with those of the water rat.

Musdin Fourth Barrow. The fourth of the group of barrows on Musdin Hill was opened on the 16th of June. It is a flat-topped barrow, 25 yards across, about three feet high, and composed of earth, with a few stones about the various interments. About half way down, in the centre, we found a skeleton, near to which was a second much decayed, but apparently of a young person; by the side of the head was a pebble, and a circular ring of bronze, with a ribbed front, which, from the remains of the iron pin, we conclude to be a brooch. Beneath the head was another like it, in better preservation. The rust from the iron pins retained impressions of woven cloth and hair, but whether the latter results from contact with a skin garment, or the hair of the corpse, it is impossible to decide: the last is, however, most probable. Under the body was much charcoal.

Slightly further on, we found a large thin instrument of grey flint, which probably belonged to a decayed skeleton reposing near upon some stones, surrounded by rats' bones. A beautiful bronze dagger, five inches long, 2½ broad, with a rib up the centre at each side, and three rivets for the handle, the polished patina of which rivals malachite in colour, was found, in no very determinate position with regard to any of these interments, though nearest to the first; if, however, we take former discoveries as a guide, we should attribute it to the owner of the flint instrument.

Of the fourth interment nothing remained but some of the smaller bones. The fifth deposit, found in a bowl-shaped cavity in the natural surface, about nine feet from the centre, consisted of bones which had undergone the process of cremation on the spot where they were buried, the depression being lined with charcoal. They were accompanied by the remains of a peculiarly ornamented vase, with perforated bosses, which had been placed near a stone. The sixth was a skeleton, accompanied by two flints, one round, the other pointed, which lay about three yards from the last.

The small bones and teeth only remained of the seventh.

The eighth had also been buried entire, though part of the skull, the teeth, and the bones of the extremities, were the only remains. Near the head were two flints of mean quaUty, and a small neatly-ornamented vase, 4½ inches high, which stood upright about eighteen inches beneath the surface. The latter has been partly broken for ages, without coming to pieces, as there is a crack half an inch wide down the side.

The ninth was the most perfect skeleton in the barrow. It lay on its left side, with the knees drawn up, and the head to the centre. The upper part was much decayed: length of femur eighteen inches.

Of the tenth little was left.

The eleventh consisted of calcined bones and the remains of an urn.

The twelfth and last was another decomposed skeleton, lying on an accumulation of stones, and accompanied by some flint flakes. Most of the interments were within a little distance of the centre of the barrow, and were surrounded by small stones laid on a stratum of charcoal; they were unusually decayed, although the bones of rats found in contact with them were well preserved.

Minninglow. On the 27th of July, excavating as near the centre of the earthy barrow [Map] [Rockhurst Barrow [Map]] as possible, we raised three or four ponderous flat stones, beneath which the earth exhibited a crystalized appearance, resulting from its having been tempered with liquid; cutting down through it we arrived at the natural surface at the depth of rather more than 4 feet, and found that the mound had been raised over the site of the funeral pile, as it remained when burnt out. The scattered human bones had not been collected, but lay strewed upon the earth accompanied by some good flints, part of a bone implement, and a bronze dagger of the most archaic form, having holes for thongs and no rivets, all of which had been burnt along with their owner. The dagger is singularly contorted by the heat, and affords the first instance of a weapon of bronze having been burnt, and the second in which we have found one associated with calcined bones, the first being at Moot Low [Map], in 1844 (Vestiges p. 51). But perhaps the most important conclusion to be drawn from the discovery is the corroboration of the opinion entertained in favour of the high antiquity of the cairns or stone barrows, and other megalithic remains of primitive industry, as we here find a mound containing an interment accompanied by weapons indicating a very remote period, and itself differing both in material and structure, occupying a position in relation to the cairn, which affords positive proof of its more recent origin.

Throwley. 18th August, we opened a barrow [Throwley Moor Barrow [Map]] on the hill behind Throwley Moor House, the dimensions of which are not ascertainable, from the greatest part of the mound being natural. We commenced digging on the north-west side, through earth one foot deep, beneath which was rock. We soon, however, arrived at a flat stone, placed upright beneath a wall that crossed the barrow; and having removed sufficient of the latter to allow us to proceed, found immediately below its foundation a large sepulchral urn, which, contrary to general usage, stood with the mouth upwards in a hole in the rock eighteen inches deep; the upper edge, from having been long exposed to the influence of the atmosphere from being so near the surface, was so much disintegrated as to be at first taken for charcoal, but we ascertained the diameter to be about fourteen inches; it is quite plain, and composed of coarse friable clay, of a brick red outside and black within. It contained calcined human bones, amongst which were the following articles - two fine pins, made from the tibia of an animal probably not larger than a sheep; a short piece cut from a tubular bone, and laterally perforated, possibly intended for a whistle; a bronze awl, upwards of three inches long, which has been inserted into a handle, and is now covered with a very dark and polished aerugo; a flint spear head; and a bipennis, or double-edged axe, of basaltic stone. All these, except the whistle and the awl, have been submitted to the fire, by which the axe had been so much injured that it was difficult to extricate it from its position under the bones at the bottom of the urn without its falling to pieces. The urn itself, being very thin and adhering to the rock, was taken out in small fragments. The few stone axes found during our researches have uniformly been associated with the brazen daggers, and were replaced by the plain axe-shaped celt at a slightly later period, but in no other instance have they accompanied an interment by cremation; indeed the instances in which the brass dagger has been found with burnt bones bear so small a proportion to those in which it accompanies the skeleton, that we may conclude there was a marked, though gradual change in the mode of burial introduced about the time when the knowledge of metallurgy was acquired. There is, however, evidence that the ancient rite of burial was resumed at a later period, dating but little, if at all, previous to the occupation of the country by the Romans.

Stanshope. On the 2nd of September [Note. This is probably December], we resumed the examination. Whilst still within the central bason, we found, near to its western limit, some bones of a full-grown human skeleton, a horse's tooth, one instrument of calcined flint, and many unburnt flakes of the same. The lower part of the barrow in this direction was chiefly composed of large stones, with but little earth amongst them, which led us to suppose that there was no interment in their vicinity, as all the other skeletons were surrounded by small stones, mixed with earth. The east side, untouched before from want of time, was next examined, where, at the depth of two feet six inches, we found the disturbed remains of a young person, covered with small stones and earth, lying on the natural surface and accompanied by rats' bones, a piece of earthenware, and some small flints. We found that this skeleton had been disturbed by the formation of a grave close to it, cut nine inches deep in the rock, for the reception of a later interment, which was discovered immediately after. This grave was irregular both in form and depth, being deepest in the middle, so that the skull and opposite extremities were on a higher level than the rest of the bones. The skeleton, which was that of a tall young man whose femur measures 19½ inches, lay on the left side in the usual contracted position, embedded in earth which presented the appearance and was actually of the consistence of mud, arising from the percolation of water through the overlying mound. A rude piece of black flint lay under the upper part of the body, and at a higher level, above the right shoulder, was an elegantly-shaped bronze dagger, 4¾ inches long, with two rivets attached, between which are two holes that have never been filled with metal, but which may have served to bind the dagger more securely to its handle, by thongs of leather or sinews of animals. It presents the corrugated surface usual on bronze instruments that have been buried in their leather sheaths, and is further enriched by the impressions of a few maggots or larvae of insects. Several small pieces of flint wers found in this grave, which at one point was only about a yard from the second discovered by the first day's excavation.

Lady Low. On the 13th of April we made a cutting in the south-east side of the tumulus, at Lady Low [Map], near Blore, first examined on the 2nd July, 1849, and discovered a heap of calcined bones buried in the earth, without any provision having been made to enclose them. In their midst lay a bronze dagger, of the usual shape as far as regards the blade, but having a shank or tang to fit into the handle, which was secured by a single peg passing through a hole in the former; the handle, where it overlaid the blade, was terminated by a straight end, and not by a crescent-shaped one as usual. The dagger had been burnt along with the body, furnishing the second instance of the kind, and the third in which that instrument has been discovered with calcined bones in our researches. We also made a further search in the other tumulus at Lady Low, where burnt bones were found on the 14th of September, 1849, but found nothing but two blocks of flint.

Hill Head. On the 20th of June, we excavated a small mound of earth near the large barrow at Sterndale, opened in September, 1846, but failed to discover an interment.

When, to occupy the afternoon, we worked a little in the large barrow, where, in 1846, a bronze dagger was found, and made two cuttings to no purpose, as we observed only remains of animal bones and pottery, some of which was of the Romano-British period, and doubtless belonged to a late interment that was found near the surface some years before by men getting stone.

Bole Hill. On the 29th of September, we examined the remains of a large tumulus at Bole Hill, on Bakewell Moor, near that [Bole Hill Barrow [Map]] investigated on the 24th of August, 1843. (Vestiges, page 47.) By measurement with a tape, the diameter was ascertained to be exactly 23 yards; about eighteen inches only in height remained, the upper part having been removed at the time of the enclosure of the common for the sake of the stone. The remainder consisted entirely of small gravelly stone, the upper moiety having been much disturbed, together with all the later interments that had been deposited above the natural surface; of these we observed the remnants of at least two, some in their natural state, others calcined. We also found a few articles of different dates, the most modem being a small piece of kiln-baked pottery, of coarse texture, and red colour, and a circular stud of green glass, which may possibly have graced the centre of a fibula, as a fictitious gem; a more ancient object was the point of a very slender bronze dagger, much attenuated by frequent sharpening; it was in two pieces, which lay some distance apart: there were many bones and teeth of animals amongst the gravel, and when we arrived at a depth that left only six or eight inches of artificial ground above the natural level, we observed innumerable rat' bones, and in the gravel just below, near the centre of the barrow, we discovered the primary interment in a state of advanced decay; it was the skeleton of a man lying on his left side, with the knees drawn up and the head to the north-east; beneath the head was a very rude instrument of grey flint, nearly round, which was the only article of man's device found near him. From the unmanageable nature of the clayey soil on which the skeleton lay, and the friable condition of the bones, no measurement of the long bones could be taken, but fortunately so many pieces of the skull were recovered as to allow of its restoration. To us it appears a remarkable example, and may be described as having the calvarium long, narrow, and conveying the idea of lateral pressure; the forehead retreating, with the frontal sinuses prominent, the facial bones large, and the upper maxiilaries, together with the lower jaw, strong and wide.

Long Stones Long Barrow [Map]. Historic England:

The monument includes a Neolithic Long Barrow aligned north east to south west and situated on a gentle east-facing slope, 300m south west of the South Street long barrow [Map].The barrow mound has been slightly disturbed by cultivation in the past but survives as an impressive earthwork which measures 84m long and 35m wide. The mound stands up to 6m high and is flanked to the north and south by quarry ditches which provided material for the construction of the mound. These have become partially infilled over the years owing to cultivation but survive as slight earthworks c.24m wide and 84m long with a depth of c.0.6m. The barrow was partially excavated by Merewether between 1820 and 1850. He discovered evidence of a Bronze Age cremation burial contained in a 'Deverel Rimbury' style pottery urn and a piece of bronze which was probably part of a dagger. The urn is now located in the [Map].