Archaeologia Volume 34 Section XIII

Archaeologia Volume 34 Section XIII is in Archaeologia Volume 34.

Account of some of the Celtic Antiquities of Orkney, including the Stones of Stenness [Map], Tumuli, Picts-houses, &c, with Plans, by F. W. L. Thomas (age 38), R.N., Corr. Mem. S.A. Scot., Lieutenant Commanding H.M. Surveying Vessel Woodlark. Read Feb. 6th and 13th, 1851.

Archaeologia Volume 34 1851 XIII Orkney Chapter I

The following Notes have been arranged partly with the view of affording the means for comparing the Celtic antiquities of the Orkneys with their prototypes situated in other countries, but more particularly in the hope of inducing some resident gentleman of more leisure and antiquarian lore to draw up a detailed description of these interesting Landmarks of Time, many of which are fast disappearing before the efforts of rural industry and agricultural improvement. There is, however, but little cause to apprehend any further dilapidation in the greater monuments of the county; an interest in their conservation is daily gaining strength, and we have the faith to believe that in a short time even a peasant will feel ashamed to remove from the inquiring presence of enlightened men an irrecoverable record of the thoughts and feelings of a by-gone race. The antiquities of the Orkney and Shetland groups will be found upon examination to be well worthy of a careful study, not only from being extremely numerous for the small extent of country in which they are placed, but also from the great diversity of their forms, in many places leaving us unable to determine the purpose for which they have been erected.

Orkney is generally supposed to have derived its name from words in the British language signifying Outer-Catti, and to have been inhabited by a branch of the Catti;a but, leaving conjecture, we find it stated in the famous diploma drawn up by Bishop Thomas Tulloch, in 1443,b that immediately preceding their conquest by Harald the Fair-haired these islands were occupied by two different races, the Pape and Peti (Pets or Picts), and that the Northmen "swa passit on the said nations of Peti and Pape, that the posteritie of thame after remained nocht."a1

Note a. "Which are said by a certain old manuscript to be so called (Orkney), as if one should say Argat, that is (for so it is there explained), above the Getes; but I had rather expound it Above Cat; for it lies over against Cath, a country of Scotland," &c.—Camden, p. 1073.

Note b. In Barry's History of Orkney: it lias since been printed by the Bannatyne Club, in the 3rd volume of their works.

Note a1. Reperimus itaque, imprimis, quod tempore Haraldi Comati primi regis Norwegie, qui gavisus est per totum regnum suum hac terra sive insularum patria, Orchadie fuit inhabitata et culta duabus nacionibus, scilicet Peti et Pape, quse duae genera naciones fuerunt destructae radicitus, hac penitus per Norwegiences de stirpe sive de tribu strenuissimi principis Rognaldi, qui sic sunt ipsas naciones aggressi quod posteritas ipsarum nacionum Peti et Pape non remansit.—Barry, p. 399.

But though the posterity of these people "passit away," they left behind them records of their social development in their sepulchres, their habitations, their castles, and their domestic and warlike implements; and such of these as have fallen under the writer's notice will be described.

Of the Pape it may be briefly stated that they are supposed to have been a collegiate Irish priesthood, introduced about the time of St. Columbab the apostle of the Picts; and, judging from the names, Paplay in South Ronaldsey, Paplay in Holm, Eynhallon, Papey Stronsey, and Papey Westrey, are places in which they have been located. It has also been pointed out to me by Professor Munch, of Christiania, that the island now known as North Ronaldsha is in Saga literature called Rinansey, which appellation he believes to be after the famous St. Ringan, or Ronan, and to have received that name before the conquest of this country by the Northmen. The Pape seem to have spread as far as Iceland, for, according to the Landnanamabok, before Iceland was colonized from Norway, there were people there who the Northmen called Papa; they were Christian men, and left behind them books in the Erse language.c

Note b. "St. Columba meeting one day with a prince of the Orkneys at the palace of King Brude, he told the King that some monks had lately sailed with a view of making discoveries in the northern seas, and begged he would strongly recommend them to the Prince who was then with him, in case they should land in the Orkneys. They did so, and owed their lives to the recommendation of Columba."—Smith's Life of St. Columba, p. 55.

Note c. Adur Island bygdist of Nordmonnum varo p'ar p'eri menn er Nordmenn kalla Papa, p'eri varo menn kristner, &c.—Johnstone's Ant. Celto-Scan., p. 14.

The ruins of many ancient buildings, both defensive and simply domestic, are ascribed by tradition to the Picts, who, instead of being magnified by the haziness of indistinct historical vision into giants or cyclops, have (probably from the very narrow passages in their castles and dwellings, and their small kistvaens), dwindled in the vulgar estimation to a race of pigmies: it is presumed that the controversy concerning their ethnographical position has long been settled, and that they were in fact a geographical division of the Celtic Britons.d

Note d. "After an interval of many years, when Brito reigned in Britain, and Posthumus his brother over the Latins, not less than 900 (about 256 B.C), the Picts came and occupied the islands which are called Orcades; and afterwards from the neighbouring isles, wasted many and not small regions, and occupied them in the left part of Britain, and remain to this day. There the third part of Britain they held, and hold till now."—Nennius, C. 5, quoted by Ritson, Annals of Caledonia.

It is generally imagined by those whose topographical information is limited to the southern portion of Britain that the island becomes more uneven as its northern extremity is approached; this is not, however, strictly the fact, for, after passing the mountain ridges which rise between the neighbourhood of Perth and the Ord of Caithness, we descend upon a simply hilly or undulating country, possessing very few romantic features, but peculiarly adapted to the labour of the agriculturist. The same topographical character occurs upon the northern side of the sea-valley (Pentland, properly Pightland, Firth) which divides the archipelago of the Orkneys from Scotland, where, instead of mountain masses separated by deep valleys, we find a swelling moorland whose mean elevation would not exceed one hundred feet. There are some exceptions to this usually tame appearance, for the hills of Hoy, of Orfer, Ronsey, and Edey have either had sufficient cohesive strength, or have accidentally escaped the denuding influence which has been going on around them; but in general the old red sandstone has been swept away, and the flagstone of the same formation, after the deposition of a few feet of boulder clay, is the floor upon which the present race of men are passing their ephemeral existene.

It is worthy of remark, that there is good evidence of the low grounds having been formerly covered by a forest of birch, hazel, and willow, which, besides forming a covert for the wild boar, red deer, and other extirpated animals, would afford fuel and shelter to the primitive inhabitants. That the native wood had become too scarce for economic purposes about A. D. 925, may be gathered from the fact that the reigning earl acquired the title of Torf-Einav from having taught his subjects the use of that substance for fuel, and this is but one generation after the occupation of the country by the Northmen.

That the Celtic or original inhabitants were very numerous is proved by the great number of barrows scattered throughout the islands; I imagine that at least two thousand might still be numbered; and when it is remembered that half as many more have probably been removed or obliterated from within the inclosures, an idea may be formed of the length of time which must have elapsed since the country was first settled. These barrows seem almost posited by accident, for they may be seen upon the very top of a hill, or upon the brow, or halfway down, upon the moor, or by a burn, or by the sea side. They are single, or in confused groups. At Stenness and at Vestrafiold there are four posited contiguously in a straight line; but I have not met with a circular, nor indeed any other, arrangement of barrows, except that they are sometimes twin, not however of equal size, but one about two-thirds smaller than the other.

The common form of the Orcadian barrows is the bowl-shape of Akerman's Archaeological Index (age 44). These barrows present exactly the outline of one-third of an orange cut through its axis. From their depressed figure they do not make a prominent appearance in the landscape. The contrary happens with the conoid barrows, which are at once remarkable from their greater height and size. It will be shewn hereafter, that there is reason to believe the conoid tumuli to be of Scandinavian origin.

There are considerable varieties in the species of bowl-shaped barrows; the simplest is a low mound of earth not raised more than eighteen inches from the ground, and about seven or eight feet in diameter: there is a group of five of these dimensions close to the Great Stenness circle (ring of Brogar), and four of them are posited in line, suggesting a relationship among the occupants in blood or destiny.

Increasing in size, they may next be noticed as about four feet in height, and twelve in diameter; these contain but one grave (kistvaen), formed by four rude slabs placed upright upon the natural surface of the moor, so as to inclose a small oblong cell; and in one opened by Mr. Petrie (age 60) and myself during the winter of 1848 the burnt bones were simply deposited in a hole scooped in the earth; a flagstone more than large enough to cover the cell was placed above it, and the earth heaped over all.

In the next rank may be placed those barrows which are from six to ten feet in height, and from twenty-five to thirty feet in diameter; one of these dug into by Mr. Petrie (age 60) and myself, called the Black Knowe, was situated on a wet moor at the foot of the ward of Rhush, in Randal. It had evidently been formed with greater care than was usually bestowed upon these sepulchres; the mound was nearly semi-circular in outline, and had a covering of a layer of peat fully one foot in thickness, but whether a sward had been originally placed over the tumulus, or it was simply the growth of time, I am unable to determine, but incline to the former opinion. Beneath the peat we came to a very pure sandy clay without any mixture of stones; but on the surface of the clay flat pieces of stone, about the size of a man's hand, were plastered here and there, evidently for the purpose of keeping the mound in shape. We found no further difference until we came to the grave, the covering stone of which was six feet below the top of the tumulus. This stone was of no determinate figure, and was without dressing of any kind, although much larger than the aperture of the cell. It was so clumsily placed that a little earth found its way into the grave before it was removed. When the covering-stone was lifted, which it required rather a strong man to do, the grave or kistvaen was seen to be eighteen inches long, one foot in breadth, and eight or ten inches in depth. The stone of this country has naturally a slaty pacture, and splits easily, so that it only requires dressing upon the edges; but this had not been done, the sides of the stones did not meet, and schoolboys in their play would construct a neater apartment. Upon an oblong stone which nearly fitted the cell were deposited an urn and burnt bones. The urn had been broken when the covering stone was placed over it, otherwise it was quite fresh and clean; it was of a dirty brick colour, of a very coarse clay, in which there were many bits of stone, and when newly burnt would not have had sufficient tenacity to have been held up by one side without breaking, The urn was about eight inches in diameter, and four in height, and of a simple basin shape. There was about a large handful of fragments of burnt bones and ashes, which had been first placed upon the stone, and the urn inverted over them; upon the outside the urn was banked up by very fine sand or ashes. This would prevent the escape of the contents, as well as keep it from sliding off the stone. Upon the whole there seems to have been but a small degree of skill exerted in proportion to the labour employed in the construction of this tumulus.a

Note a. "Several other tumuli have been opened, which had much the same appearance. In some of these were found stone chests of about 15 or 18 inches square, in which were deposited urns containing ashes; in others of these chests were found ashes and fragments of bones without urns.

"In digging for stones in one of these tumuli was found an urn, shaped like a jar, and of a size sufficient to contain 30 Scotch pints (15 gallons English). It contained ashes and fragments of bones. The colour on the outside was that of burnt cork, and on the inside grey."—Old Stat. Ace. p. 459.

The Rev. Charles Clouston in his Statistical Account remarks that "barrows or tumuli are particularly numerous in Sandwick. I believe there are more than one hundred, though it would be neither easy nor useful to count them. Eight of these situated upon the common have been opened during the last year. A minute description of each would be tedious, but a brief account of the most important, which I opened in company with most of the other office-bearers of the Orkney Natural History Society, must be interesting to the antiquarian. The first, which was the largest of a numerous cluster between Vog and Syking, was fifty yards in circumference, and about seven feet and a half high. It was formd of a wet adhesive clay. On reaching the centre, we found a large flag, which formed the cover; and on raising it up, the grave appeared as free from injury, and the pieces of bone as white and clean, as if formed only the preceding day. At its end, which lay north-east by east, was an urn inverted, shaped like an inverted flower-pot, and at its other end about a pot full of bones unmixed with ashes, which had been burnt and broken small, none being more than two inches long and one broad, covered by a stone of an irregular shape about one foot across. It was sprinkled with a peculiar mossy-looking substance of a brown colour, and white ashes, which seemed from the smell, when burnt, to be animal matter. The surface of the urn was dark, not unlike burnt cork, and seemed to be rude earthenware,, into the composition of which bits of stone enter liberally. It contained nothing that we could perceive, and soon fell to pieces; but I put them together with Roman cement, and it is now safe in the Society's museum, with part of the bones.

"The next in size of the group of tumuli was thirty-four yards in circumference, about six feet high, and contained six separate graves.a The two nearest the centre seemed the principal ones. A large flag rested against the covers of them on the east side, jutting up about a foot above them. It measured five feet long, four feet two inches broad, and three inches thick. The space under this flag was quite empty. On removing it and the two horizontal covers on which it rested, the two principal graves were exposed to view. The first was formed of a double row of upright flags on all sides except the south, next to the second, where there was only a single row, and small pieces substituted at the corners; the space inside was filled for nine inches with clay, and the corners of this and the second were also cemented with it. Between the cover and clay flooring was a vacant space about a foot deep, into which some fine sand had penetrated or fallen from the cover in wasting, and sprinkled the floor. On removing this, we found a small stone, which covered a cavity in the clay one foot in diameter and nine inches deep, containing the bones, burnt and broken as in the first tumulus, and some little pieces of charcoal. This grave was one foot eight inches square inside; the outside flags were six inches higher than the inner ones, and those on the west and east sides very thick. Outside they were supported by some lumpy stones and the clay.

See the accompanying Plan, IV.

"The second grave (which was one foot ten inches by one foot three inches across the middle, but far from square, and two feet deep,) was nearly one foot south of the former, and consisted of four flags, set up on a floor of flag, with a heap of bones similar to those in the first. The third was at the south side, close by the west corner of the second, and was very simple, being merely a cavity in the earth covered by a stone on-which we were treading; and being so low, without any upright flags about it, it escaped observation till we were about to leave the tumulus. It contained pieces of bone of a larger size than the former two, and a few pieces of a vitrified substance, like a parcel of peas with a vesicular internal structure, and of a whitish appearance, as if it were vitrified bone. The fourth grave lay on the east of the first, with a space of three feet between; internally, it was two feet ten inches long, by two feet three inches broad, the inner row of flags six inches below the level of the outer; nine inches below that was a small cover stone, and at the bottom six inches of peat ashes, with bits of bone. The fifth lay two feet south of the last, and was about three feet five inches by two feet three inches. It was formed by a single row of flags without any cover On the top was six inches of clay, and below that about nine inches of ashes and bone. The sixth lay three feet from the north-west corner of the first, and was the rudest of all. It measured two feet by one foot two inches. All these graves lay with one end north-north-east, except the sixth, which was directed north-east. This resemblance between the fourth and first is worthy of notice,—that it also consisted of a double row of flags upon all sides except the south, next to the fifth-, where it was single."—P. 57.

In the fourth grade of bowl-shaped tumuli may be considered those whose circumference is bounded by a ring of rough blocks of stone, like the first course of a modern stone dyke. This prevents the earth of the tumulus from spreading, and preserves its shape..Many of these, which are almost flat on the top, may be seen on Vestrafiold, in Sandwick; they are about twenty feet in diameter and four in height.a Another variety of bowl-shaped tumulus is that having a ring of small upright stones standing around the barrow. I am only able to cite one instance, on Vestrafiold, where there are but one or two stones left, about two feet in height.

Note a. "I lately made excursions to St. Andrew's and the farm of Wideford in this parish (St. Ola), and opened two graves at the former place, and three at the latter; they all appear to be of the same date. I opened one of the largest, which was of greater diameter than the one we explored in Rendal (the Black Knowe), but not quite so high. It had a sort of circle or ring of burnt stones about afoot in breadth, and the thickness of one stone, immediately within the edge of the base. In the centre, embedded in clay, was a layer of burnt bones mixed with charcoal, about three inches in thickness. There was no kist-vaen, nor any stones near the bones."—G. P.

There is yet another variety of these tumuli, where upright pillars are situated upon the mound, of which the Knowe of Cruston was, and Stoneranda (Stoneround) is (both in Busa), an example.

None of the tumuli previously described are remarkable for height; on the contrary, they are low and broad; nor does the interior arrangement constantly advance with their external decoration; for the Knowe of Cruston, although surmounted by a standing stone four or five feet in height, did not contain any urn, but only burnt bones in a common cell, and in those described by Rev. C. Clouston (ante) it is seen in one instance that the large family-barrow contained no cinerary urns, and in the other, that the bones were deposited in a hole at one end of the grave, while the empty inverted urn was placed at the other.

I have never heard of any gold ornaments, or stone or other implements, being found in Orkney, in the graves of those who burned their dead, though such may yet be discovered

Archaeologia Volume 34 1851 XIII Orkney Chapter II

It is generally known that the Orkneys are naturally divided into the north and the south isles by the island of Pomona,a which is also very appropriately called the mainland, for it is fully equal in size to one-third of the whole group; but its figure is very irregular; the eastern half is so deeply intersected by several large bays as to be in one place but a mile from sea to sea. The west mainland, that is, so much of the island as lies upon the north side of a line joining the Bay of Firth to the Bridge of Weith, is, on the contrary, bounded by nearly straight coasts, and may be roughly estimated as about ten miles in length and breadth. Parallel, and near to the coasts, are ranges of hills of moderate elevation, from 200 to 500 feet, sufficiently high to exclude a view of the sea from a large and tolerably level area, and here the parish of Hana has the solitary distinction of not having the ocean on any side to form its boundary. This district or heneda1 is in a great measure occupied by two large lakes, yet most unaccountably they are usually considered as but one, and both have been known by the same name, the Loch of Stenness, although their connection is only by means of a narrow ford about 120 yards in breadth; besides the sea occasionally ebbs and flows in the southern lake, and the water is salt, while the northern is tideless and filled with fresh water.

Note a. It is very singular that the Scandinavian name of this island should be so entirely forgotten. In the Orkneyinga Saga it is usually called Hrossey or Rossey, and it is so named in a map appended to Camden's Britannia; it appears to mean "the Island of horses."

Note a1. Hened, jurisdiction, district, hundred.

The two promontories dividing these lakes are known collectively as "Stenness" (Stone-ness), but individually as Stenness and Brogar. The latter name, which is applied to the northern point, is derived from the Scandinavian bro or bru, a bridge, and gard, an inclosure. Until lately stepping stones enabled the foot passenger to cross the ford dry-shod; but a sort of bridge-causeway now supplies a less adventurous mode of transit: this is the Bridge of Brogar.

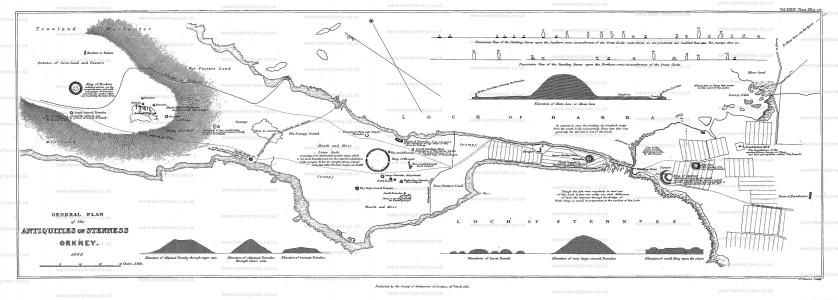

This neighbourhood has been consecrated ground, or the holy land of the ancient Orcadians; for there are within the distance of two miles no less than two rings or circles with circumferential columns, two others without erect stones, four detached pillars or standing stones, besides about twenty bowl-shaped and conoid barrows, some of them of large dimensions, and presenting great diversity in their proportions and magnitudes; as well as the remains of cromlechs and tumuli too much destroyed to admit of their peculiarities being distinguished.

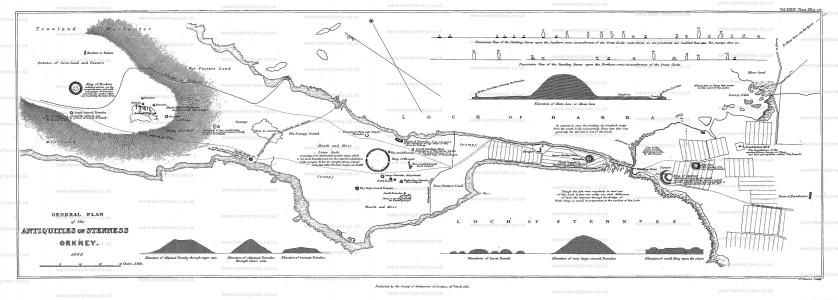

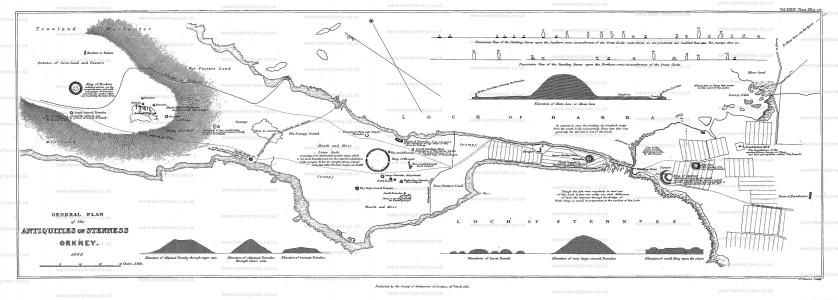

In the winter of 1848 I undertook a survey of these antiquities, wishing to leave a permanent record of their present state and position, while they were yet in tolerable preservation; but, although a labour of love, it was not accomplished without much difficulty, principally owing to the uncertain state of the weather and the distance of the locality from my residence. After a long ride, there was first to lay out the surveying poles, then shoulder my theodolite, and march from station to station through the most insinuatingly melting snow that I ever remember to have felt, often being obliged to leave my instrument and run for a quarter of a mile, to gain a little warmth by the exertion. It was, however, sometimes exceedingly romantic to hear the wild swans trumpeting to each other while standing under the lee of a gigantic stone, till a snow-squall from the north east had passed over; but, could I have attuned my soul to song in such a dreary situation, instead of raving with Macpherson, my strain would certainly have been something in praise "of the bonnie blythe blink o' my ain fireside." Occasionally there is some fine weather even in this inhospitable climate; but I can only remember the many nights, dark, bleak, and cold, in which I have been urging my easy-going quadruped over that weary road while the snow fell into my eyes upon any attempt being made to look a-head. At last, however, the survey was finisheda; with Mr. Robert Heddle, the dimensions and an outline figure of every stone in the Ring of Brogar was taken; and Mr. G. Petrie (age 60) assisted me in measuring the diameters of the circles, trenches, &c. The General Plan was made by triangulating with staves, and a base measured by a land-chain on the level point of Stenness.

Note a. See General Plan, Plate XII.

I shall now proceed to describe these antiquities in the order of their rank or development, commencing with the lowest in the series, the bowl-barrow. Around the great circle (Ring of Brogar) there are about ten of these barrows, of which the elevations are given in Plate XII.; they vary in height from eighteen inches to six feet, and in diameter from seven to eighteen feet. Far beyond the limits of the plan they occur in great numbers, and those described by Mr. Clouston, which are but two miles distant, will convey a notion of their structure and contents.

Close by the Ring of Brogar there is a ring or small barrow, about fifteen feet in diameter, but almost obliterated. There is a small standing stone still erect upon the circumference, and the stumps of two others may be seen at the angles of a square, so that it is very probable a fourth originally stood there to complete the figure.

Just without the division dike of the parishes of Stenness and Sandwick, upon the shore of the south lake, there is a small ring,b in good preservation, of great use when comparing these antiquities with each other, for it is a simple bowl-barrow, but distinguished by being inclosed within a circular embankment of the same height and material as the barrow. The barrow is forty feet in diameter, and not more than three feet in height, and is almost flat on the top. The trench is shallow, and about fifteen feet broad; not excavated, for the bottom corresponds with the natural surface. The ring-embankment (about five feet broad) is almost entire, except on the water side, where the peasants drive their carts over it to avoid the soft ground in the vicinity; it is to be hoped that the fortunate proprietor of this extremely ancient and interesting earthwork (for the common is in process of division) will take care to prevent its further injury. The diameter to the outer edge of the bank is ninety-four feet.

Note b. This ring is marked upon the General Plan; and there is a ground plan and elevation in Plate XIV.

At a very short distance to the northward are the remains of two obscure contiguous circles,a which appear to be of the nature of cromlechs: they are formed by a ring embankment of earth or stones; the interiors of both, corresponding with the natural level, have indications of flag stones arranged in two parallel lines, between two and three feet apart. It is very probable that these were graves from which the covering and other stones have been carried away.

Note a. Marked upon the General Plan.

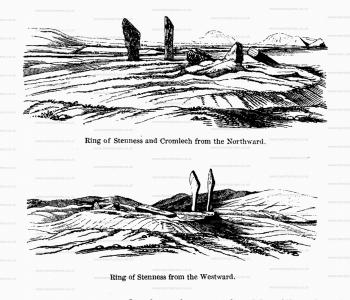

The lesser stone circle of Stenness, called here for the sake of distinction the Ring of Stenness [Map],b is a remarkable structure upon the low level point at the south side of the Bridge of Brogar, and, though considerably dilapidated, still presents sufficient of its original form to determine its dimensions without difficulty. It is indeed rather a matter of surprise that so much of it should be left for the delight of the antiquary, when it is considered that this ground has probably been under cultivation for nine hundred years. It is stated in Olaf Tryggvesson's Saga that one of the earls of Orkney was stopping at Stenness about A.D. 970; and I believe the site of the brû was not far from where the church at present stands, at least tradition says the palace stood there.

Note b. There is a ground plan and elevation of it in Plate XIV.

The Ring of Stenness resembles in its earthworks the smaller one formerly described, but is much larger, and is besides decorated with standing stones. It is formed by an interior raised mound, which is nearly or quite flat on the top, and slopes almost imperceptibly towards the trench; at the margin there are now three columns, two erect and one prostrate, and the stump of a fourth can be detected. From these it was found, on the assumption that the pillars were at equal distances apart, that twelve would complete the circle. The pillars are massive slabs of flagstone of their natural shape, and without dressing or carving of any kind. They stood in a circle whose radius is fifty-two feet, and about eighteen feet high.

This ring is peculiarly interesting from the presence of a Cromlecha within the area, but it is not placed at the centre. Though the cromlech is overthrown, it is sufficiently perfect to understand its former shape. One of the legs or supporters remains in situ, and is an unturned block rising three feet above the ground; another leg of the table, of the same size and figure exactly, has fallen outwards, and lies upon its side, while the covering stone, which is a rectangular slab 9x6x½ feet in dimensions, partly rests upon the last; the other two legs have been taken away. It may be here remarked in the instance of the only other two cromlechs known to exist in Orkney, that they also are overthrown.

Note a. In the old descriptions of Druidical (?) circles, there is generally mention made of an altar (cromlech) standing within them, either in the form of a stone table or a single upright pillar.

The ruthless plough has been driven by barbarous men over this enduring record of the thoughts and labours of an exterminated people, and even within this century some of the pillars have been destroyed to clear the ground. The unlucky tenant of the adjoining farm has exercised his "little brief authority," and a most unenviable immortality has attached to him in consequence," for, "says Mr. Peterkin, "one (of the standing stones [Map]) has lately been thrown down; three were in the month of December, 1814, torn from the spot on which they had stood for ages, and were shivered to pieces." As Mr. Peterkin speaks rather apologetically for the man, he is not to be suspected of exaggeration; yet this statement does not correspond with the plates in Barry's History, nor the drawings of the late Marchioness of Stafford. At this moment there are two stones erect, and one prostrate, but perfect; and in the drawings referred to there are but four erect stones; hence the tenant of Barnhouse could have broken up but one of these stones (exclusive of the Odin Stone [Map]), and one he prostrated.

The circumscribing ring, which is a raised earthwork of the same height as the included mound, can only be traced for one-third of the circumference, and this has led some persons to imagine that this structure was but a semicircle from the beginning, and I believe a fanciful theory has been founded on that presumption.b

Note b. A very amusing account of the Stenness antiquities will be found in a paper on the "Tings of Orkney and Shetland," in vol. iii. of Arch. Scot.

If ever this ring was completed, the massive and approximated pillars must have produced a magnificent effect, particularly if it contained the tombs of those whom men delighted to honour; but it may have happened that, as with some other great intentions, the design exceeded the means of execution; and this opinion gains support from a fact noticed by the intelligent and scientific minister of Sandwick. Upon the south side of Vestrafiold, which is about six miles to the westward of Stenness, the flagstone of this formation crops out at the surface in parallel ridges of several hundred yards in length, and from these enormous blocks may be detached without any excavation. There are at present several massive stones set free and ready for transport, and, if I am not deceived, their style is that pertaining to the Ring of Stenness rather than to the Ring of Brogar.

Dimensions of the Ring of Stenness. FEET.

Diameter of circle on which the pillars are pitched... 104

Do. to bottom of slope of interior Mound.... 162!

Do. to inner foot of bank...... 198

Do. outer ditto....... 234

Height of Mound and embankment above the natural surface, about.. 3

Dimensions of easternmost pillars erect.... 17.4 x 6 x 8/12

Do. adjoining ditto, erect..... 15.2 x 4 x 1¼

Do. nexta ditto, prostrate..... 19 x 5x 1⅔

The bottom of the trench corresponds with the natural surface

Note a. This is computed to weigh 10.71 tons.

The site of the Odin Stone [Map]b was pointed out to me by a man who had looked through it in his youth; it stood about one hundred and fifty yards to the northward of the Ring of Stenness, but it does not ppear to have had any relation to that structure, though it is probable that it was erected at the same era. All that can now be known of it must be learnt from Barry's or the Marchioness of Stafford's drawings, for the unfortunate tenant of Barnhouse cleared it away. The stone, which was of much the same shape as those still left, was remarkable from being pierced through by a hole at about five feet from the ground; the hole was not central but nearer to one side. Many traditions were connected with this stone, though with its name I believe them to have been imposed at a late period; for instance, it was said that a child passed through the hole when young would never shake with palsy in old age. Up to the time of its destruction, it was customary to leave some offering on visiting the stone, such as a piece of bread, or cheese, or a rag, or even a stone; but a still more romantic character was associated with this pillar, for it was considered that a promise made while the plighting parties grasped their hands through the hole was peculiarly sacred, and this rude column has no doubt often been a mute witness to "the soft music of a lover's vow."

Note b. "At a little distance from the temple is a solitary stone about eight feet high, with a perforation through which contracting parties joined hands when they entered into any solemn engagement, which Odin was invoked to testify." (Arch. Scot. vol. iii. p. 107.) This agrees with the description of Mr Leisk; but Barry's plate would lead us to imagine that the height was at least double that given above.

Close to the east end of the Bridge of Brogar stands a single gigantic pillarc of about the same size and shape as that marked a in the Ring of Stenness. There is no appearance of earthworks or structure near it, and I have remarked that these bauta stones, of which I can reckon up about a dozen in Orkney, are not distinguished by having a tumulus or barrow near them

Note c. It was called "The Watchstone."—Arch. Scot. vol. iii. p. 108.

A little way to the eastward of the Ring of Stenness, is a mound called "Big How," but of what nature I am unable to decide, and it would require considerable excavation to make out its details—its position is shown upon the plan: and at the north-west end of the Bridge of Brogar is a large dilapidated tumulus, which appears to be the ruin of an ancient stone building, perhaps a Pict's castle; close by it are two small standing stones.

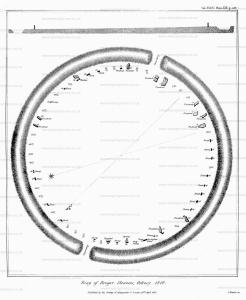

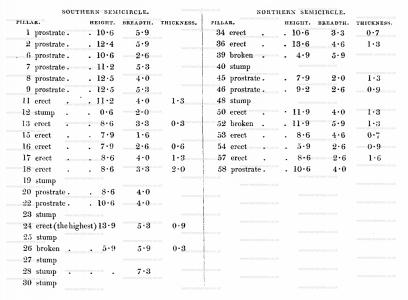

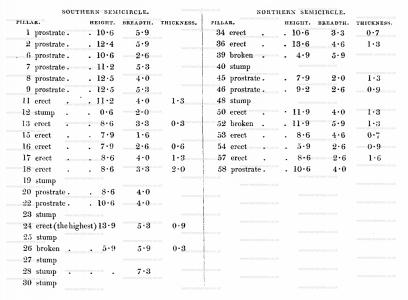

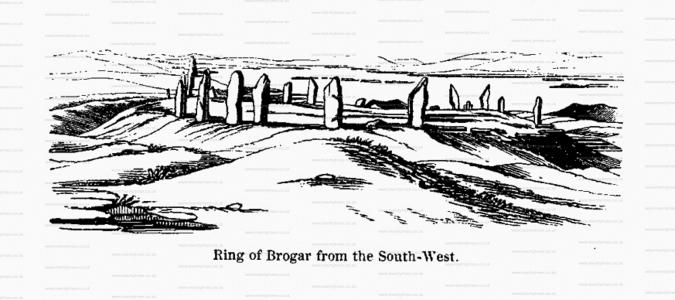

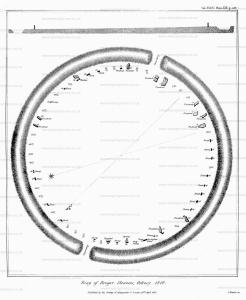

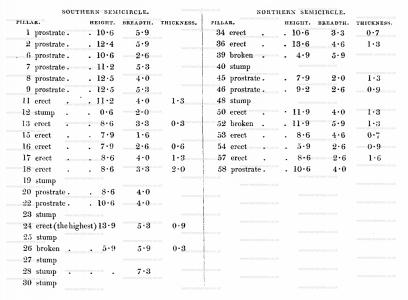

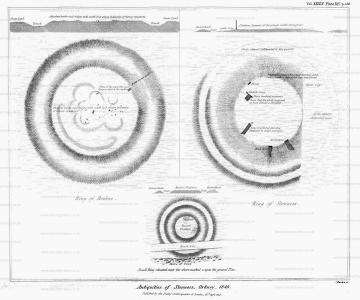

But the most considerable of all the antiquities of this district, is the great circle of Stenness, or Ring of Brogar [Map].a. This is a deeply-entrenched circular space, with a diameter of 366 feet, and containing two acres and a half of superficies. No peculiarity is observable in the topographical character of this place. The area is neither level nor smooth, for the natural undulations of the ground traverse the inclosure. Around the circumference of the area, but about thirteen feet within the trench, are single, large, erect stones or pillars, standing at an average distance of eighteen feet apart. These stones appear to be the largest blocks that could be raised in the quarry from whence they were taken, and are without dressing of any kind; hence, their figure is not uniform, and they vary considerably in size; the highest stone was found to be 139 feet above the surface, and, judging from some others that have fallen, it is sunk about eighteen inches into the ground. The smallest stone is less than six, but the average height is eight or ten feet. The breadth varies from 26 to 7'9 feet, but the average is about four feet, and the thickness one foot. No order can be traced in the relative size or figure of the remaining stones; small and large succeed each other indiscriminately. To mineralogists they are known as the flagstones of the old red sandstone formation, and are supposed to have once been mud, which has been aggregated into sub-crystalline forms by molecular forces.

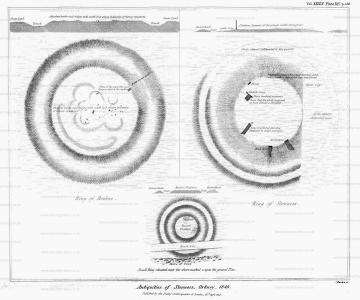

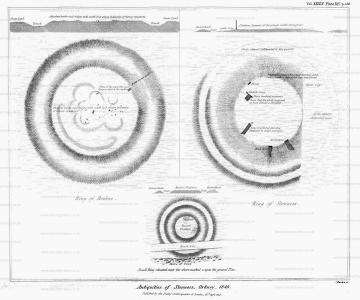

Note a. See the General Plan, and Plate XIII. for an enlarged Plan and Elevation.

It appears that the number of standing stones, on the assumption that they were placed at nearly equal distances apart, was originally sixty, but there are now only thirteen erect and perfect; ten others are nearly perfect, but prostrate; and there are the stumps or fragments of thirteen more; in all thirty-six. So that twenty-four (if the above assumption is correct) have been entirely obliterated.a

Note a. "The number of stones which originally formed the temple is supposed to have been thirty-five, but this is uncertain; sixteen were standing in the year 1792, and eight had fallen to the ground."—Arch. Scot. p. 108.

The trench around the area is in much better preservation than could have been expected from the lapse of years; the edge of the bank is still sharply defined, as well as the two footbanks or entrances (to the circle) which are placed exactly opposite to each other; they have no relation to the true or present magnetic meridian, but are parallel to the general direction of the neck of land on which the circle is placed. The trench is twenty-nine feet in breadth, and about six in depth, and the entrances are formed by narrow earth-banks across the fosse. It has been imagined, but without sufficient reason, that the earth or rubbish from the trench has been taken to raise the surrounding tumuli; but had these tumuli been coetaneous with the Ring of Brogar and the materials from that source, some order would have been observed in their position with regard to the great circle. Besides, as we certainly know that they are sepulchres, and are confident that their magnitude is in proportion to the importance of the individual or family they contain, it would follow that an unusual murrain had occurred among the mighty ones of the day, that so many should want sepulture while the Ring of Brogar was in process of construction.

There are now no indications of structure within the area nor has it been either smoothed or leveled: but it must be observed that not only has the peat or turf been cut for fuel, but every layer of soil has been removed, as fast as it has formed, to serve as manure for the infield. The general appearance of the country is sufficiently uninteresting; but a barren and desolate aspect, not natural to the place, is produced by the practice of paring the soil from the outfield,b that is, from all the land lying without the inclosures; and the Ring of Brogar has had no sanctity with these barbarous depredators, as the broken and scarified turf will witness.

Note b. As the division of the common is now taking place, it is probable this destructive practice will cease.

The surface of the area of the ring has an average inclination to the eastward; it is highest on the north-west quarter, and the extreme difference of level was estimated to be six or seven feet: the circumscribing trench has also the same inclination, and it therefore could never have been intended to hold water. In winter, when the lower half is partly filled, the rain water is flowing over the brim before it has reached the foot of the causeways.a

Note a. See General Plan.

About a mile to the northward of the Ring of Brogar is a large deserted quarry, quite capable of supplying all the pillars or standing stones for that entrenchment (the only man who has attempted to work there of late years gave it up, in consequence of finding the rock so hard and intractable); but it has also been stated by those whose opinion I have reason to respect, that the shore of the south loch, close by the hill dyke of Sykin, is the spot from whence the stones were taken; it is also possible that they were brought from the quarry on the south side of Vestrafiold, mentioned in a former page.

Dimensions of the Ring of Brogar [Map]. FEET.

Diameter of circle on which the pillars are placed... 340

Distance of pillars from edge of fosse or trench.. 13-2

Diameter to inner edge of fosse..... 366 • 4

Breadth of fosse....... 29

Diameter to outer edge of fosse.....424-4

Depth of fosse—average..... 6 • 0

Distance of pillars apart—average breadth of causeways... 17 • 8

Highest pillar......13-9

Lowest ditto......5-9

Average height.......9-0

Broadest pillar, stump only remaining....7* 3

Least breadth.......1- 6

Average ditto.......5- 0

Average thickness.......1- 0

The following are the dimensions of the pillars (see panoramic view)a which are numbered on the assumption that there were originally sixty (thirty in each semi-circle). The numbers begin from the south-eastern entrance, and pass towards the south:-

Note a. See the upper part of the General Plan, Pl. XII.

We will now pass by the tumuli about the Ring of Brogar for the present, and proceed to the northward for a mile, when we come to the ancient quarry, where there are four or five bowl-shaped tumuli, perhaps the graves of those who have been killed by accident when working for the standing stones, or the facility for collecting a heap of rubbish may have induced their relatives to fix upon this locality, but this is an unchai'itable conjecture. The land here rises to about seventy or eighty feet above the lakes, and is known as the Black Hill of Warbuster. Proceeding along the ridge for a quarter of a mile, we arin srive at the Ring of Bûkan, which seems to have escaped the notice of all those who had described the antiquities of Stenness, until we find it mentioned in the Rev. C. Clouston's statistical account of the parish of Sandwick; it may indeed be easily passed without attracting attention.

The Ring of Bûkan (in Plate XIV) is a circular space surrounded by a deep excavated trench, thus far resembling the Ring of Brogar, but it wants the circumferential stones, and besides the interior shews evident marks of superstructure. Many stones of small size are apparently in situ, yet no order could be traced among them; one is erect, about three feet in height, and one foot square. A triangular-shaped block, making a comfortable seat, occupies the centre, while another, completely identical in size and figure, is prostrate upon the circumference of the ring. Even this deeply-intrenched spot has been ravaged by the plough, and the industry of the agricultural savage has no doubt been rewarded by as much grain as might fill his cranium, but certainly not his stomach. Within the area there is the appearance of five or six small tangental circles about six feet in diameter, and formed of earth; within these the stumps of stones are prominent; the whole is too obscure to admit of any statement concerning it to be made with certainty, but I conjecture that these compartments are the remains of small cromlechs long since destroyed, and that the triangular stone lying at the edge of the ring has been dropped there by the boors, who have found it too heavy to be transported further from its original position, which was near to its twin at the centre.

Dimensions of the Ring of Bukan. FEET.

Diameter of internal area......13 6

Breadth of trench....... 44

Diameter to outer edge of trench..... 224

Depth of trench, about...... 6

Except on the north-east side, the bank is still sharply defined. This ring appears to have been completely isolated, and without any footway across the fosse; but the trench will not retain water, for the bottom remained dry in what was, even in this climate, called a rainy winter.

The remaining antiquities of Stenness to be described are the Conoid Tumuli. These have been purposely retained to follow the others from the belief of the writer that they are not Celtic, but the tombs of the early Scandinavians.a The reason for this opinion is soon stated: the bowl-barrows, so numerous throughout the Orkneys, are constantly found to contain the ashes (bondfide) of the dead; the conoid barrows are known to be the sepulchres of those who buried their dead entire, and usually in a bent posture. This alone shows a difference of race, although both might be living (or rather dead) at the same epoch; but the argument having most weight with the critical antiquary is this, that silver ornaments have been found in the tombs. Although this paper is intended to be but a dry record of fact, it would be negligent of the writer to describe as Celtic, or without some remark, a monument which he believes to belong to the Northmen. The Conoid Tumuli are few in number; but six exist at Stenness, where they are readily distinguished by their greater height in proportion to their base.

Note a. In a large district or country, presenting great difference in topographical feature, it is possible that the antiquities of two co-existent races may be found together; but this is not likely to occur in a comparatively small group of islands like the Orkneys, where, according to the custom of the-savage warfare of those times, the conquerors would most assuredly extirpate the conquered; thus Scandinavian rites and observances would at once supersede those of the Picts or Celts.

About one hundredyards down the Brae upon the south side of the Ring of Bukan stands a large tumulusa just without the hill-dyke of the townland of Warbuster, in the south-west extremity of the parish of Sandwick, which was exeavated last summer by Mr. Wall of Skaill, Rev. C. Clouston, Mr. Ame, the officers of Her Majesty's cutter "Woodlark" &c. It had previously been dug into by Dr. Wall of Skaill, who had trenched from the south-west side into the middle without finding any indication of structure. We now began by cutting a trench, three or four feet wide, from the south side towards the centre, and, not finding any thing remarkable, the hole at the centre was enlarged to six or seven feet in diameter, but the labour of the day was expended in a useless search.

Note a. Marked upon the General Plan, to the reader's left.

This tumulus is made of much coarser materials than is usual with the bowl-barrows, there being but little earth in comparison with the many large angular pieces of stone, such as would be thrown from a quarry, or when making a drain; but I entertain no doubt of its being formed from the subsoil of the adjacent moor. This tumulus is seventy-one feet in diameter and ten or twelve in height; but it appeared much larger until submitted to actual measurement. On a subsequent occasion, when some labourers who had been making a road hard by were present, they declared it would take half a dozen of them a fortnight to raise such a heap.

We met again on the 31st of July, and the day was nearly expended in digging at the centre, but we came upon the natural surface without finding any grave. We learnt, however, that the ground had received no preparation previous to the formation of the tumulus, for the heath and moss which had then been growing was the foundation upon which it was erected. Dr. Wall now directed attention to a few moderately large pieces of flagstone that had been passed when trenching in, when a few strokes of the pick soon made it apparent that we had hit upon some structure, and in a little while we came upon a grave. This was placed about half-way between the centre and circumference of the tumulus, that is, about ten feet from the centre and four feet above the natural surface. The top stone of the grave was a large unsquared slab, not made to fit in any way, but overlapping the sides considerably; this was very carefully cleared to prevent the earth falling in upon its removal. On lifting off the top stone, the grave was seen to contain a human skeleton, which was lying upon the right side, with the legs doubled close up to the abdomen. The large bones of the arms and legs were nearly and the skull was quite perfect; some of the teeth had fallen out, they were much worn but otherwise good. The bones of the spine and pelvis had decayed; no remnants of clothes nor ornaments could be detected. The grave was conjectured to be that of a female of full age, from the small size of the bones (femur, 17f inches; tibia, 14^ inches), the decidedly marked attachments for the muscles, and the worn teeth. Though I do not attach much importance to the circumstance, it is necessary to state that the grave was in the direction of the prime vertical (east and west), and that the skull was in the north-west quarter, with the face towards the east. The sides of the grave were neatly built, but no bottom slab could be detected; it was evident that the occupant must have been squeezed in, probably swathed in the native cloth of the country (wadmal). The capacity of the grave is 36 X 27 X 18 inches.

After our curiosity was satisfied, the grave was re-covered and closed up. This finished our operations for the day; but a short time afterwards this tumulus was]'again explored by a party from the "Woodlark," when it was considered advisable [to commence operations exactly opposite to where we had been working before; accordingly a trench was begun in that quarter, and almost immediately a grave was found. It appeared to be of a ruder description than that previously described. The walls or sides were formed of single upright flags, and the covering stone, which had fallen in, had disturbed the contents. The grave contained nothing but the displaced bones. These had belonged to a large man, but on a comparison with the graceful proportions of my companiona it was found the latter had undoubtedly the advantage in stature. Although this grave was placed opposite to the former, and at nearly the same distance from the centre, it was six or seven feet higher up in the tumulus, and not more than one foot beneath the surface. In the lapse of years, the rain and wind acting upon so steep a mound of earth, must have much reduced its height, and consequently have brought the grave nearer to the surface; in stormy weather pieces of stone the size of a man's fist are set in motion by the wind.

Note a. Rev. C. Clouston.

A cut was now made upon the east side, perpendicular to a line joining the graves already found, when another was qxiickly discovered. It was at nearly the same level with the last, perhaps a foot higher, and slightly nearer the centre; it was but one foot beneath the surface. This grave was still smaller than either of the others. The covering stone had fallen in; the sides, less than a foot in height, were formed by two placed stones upon each other. Only a few bones were seen; they had belonged to some young person, perhaps twelve or fourteen years of age.

We had good reason to imagine that a fourth grave would be found opposite to the last, but the very large quantity of earth thrown on that side from the interior of the tumulus discouraged any attempt to search for it.a

Note a. "A tumulus containing three stone chests was opened in the parish of Sandwick, by Sir Joseph Banks, in the presence of Dr. Solander, Dr. Van Tioch, and Dr. Lind, on their return from Iceland in 1772. In one of these chests or coffins was found a human skeleton lying on its side with the knees bent; in the hollow of which was found a bag which appeared to be made of rushes, and contained a parcel of bones bruised small, and also some human teeth." It was supposed by Sir Joseph Banks and Dr. Solander, that this bag contained the remains or ashes of his wife, or of some near relation, after burning.(?)

"In the second of these chests was found a skeleton in a sitting posture, as if seated on the ground, and the legs stretched out horizontally. To keep the body erect, stones were built up opposite to the breast as high as the crown of the head. The whole was covered with a large stone.

"In the third chest was found in one end the bones of a human body thrown together promiscuously; in the other end, a quantity of chesnut-coloured hair, covered with a turf, and under the hair about four dozen of beads, flattened on the sides, lying as if on a string, about the middle of which was a locket of bone, and underneath the beads a parcel of bruised bones like to those found in the bag in the first chest. When the hair was first touched, it appeared rotten, and the beads friable; but when exposed to the air, the hair was found to be strong and the beads hard. The beads were black, but it could not be discovered what they were composed of."—Old. Stat. Ace. p. 459. I think there is some account of these explorations in the Transactions of the Royal Society.

The peculiarities of this tumulus are, 1. that no object should occupy its centre, which is contrary to former experience; 2. that the graves should be placed at the cardinal points of the compass; but this must be regarded as accidental, for at the time this tumulus was erected the deviation of the compass-needle was very different to what it is now; they must therefore be considered as placed in a circle in the tumulus; it appears to have been a family tomb for father, mother, and child; and 3. that the bodies were not incinerated, but interred in a bent posture.

Several bowl-barrows are near, and scattered about the moor are many lumps of cramp or vitrified stone, some of which are built into the hill-dyke of the adjoining townland of Warbuster.

A large conoid tumulus (6) fifty feet in height, and twenty-nine feet in diameter, stands 150 yards to the westward of the Ring of Brogar.a It has been explored at some former period, and it is not improbable that this is the one to which Wallace alludes when he says that "in one of these hillocks, near the circle of high stones at the north end of the Bridge of Stennis, there were found nine fibulae armillae) of silver, of the shape of a horse-shoe, but round." From the drawing they appear to have had the same form as those figured in plate vii. of Arch. Index, and probably met the same fate.

Note a. For its elevation see the General Plan.

A short distance to the northward of the Ring of Brogar, and near to, but not at, the shore, there is another tumulus of peculiar form.b It may be aptly compared to the shape of a plum-cake, for it is circular, and rises nearly perpendicular for five feet, when it becomes almost flat on the top, or rather is surmounted by a very depressed cone. Its diameter is sixty-two feet, height nine feet. This has never been explored, though I believe the gentleman upon whose property nearly all these antiquities are situated, and who is also a zealous antiquary, proposes to do so shortly.c

Note b. Ibid.

Note c. David Balfour, Esq. of Balfour.

The only example of the elliptical or long barrow existing in Orkney (that I am aware of) occurs upon the shore of the North Loch, 100 yards to the eastward of the Ring of Brogar. It measures 112 feet in the direction of its major axis, while its minor is but sixty-six feet, that is, it is twice as long as it is broad.'d The level ridge on the top is twenty-two feet, and its height twenty-two. The west side is so steep as to be difficult to clamber up. On the opposite side it has been dug into, but not recently, and it may be that from this one the fibulae mentioned by Wallace were obtained. There is a fine spring of water at the foot of the tumulus upon the loch side, and not unfrequently in summer a group of hungry antiquaries may be seen gazing with fixed attention not into the musty recesses of a kistvaen, but the still more interesting interior of a provision-basket. All these large hillocks are covered by a short green turf, which renders them picturesque and pleasing objects.

Note d. See General Plan.

But the most remarkable tumulus in Orkney is situated a mile to the north-east of the Ring of Stenness, and is called M'eshoo or Meashowe [Map].a This is a very large mound, thirty-six feet in height, and ninety'two in diameter, and is of a bluntly conical outline. The mound occupies the centre of a raised circular platform, which has a radius of eighty-six feet. This is surrounded by a trench twenty feet in breadth, and a circular bank probably inclosed the whole. Many attempts had been made to explore it, as there are several small heaps upon its sides; but at last sufficient force and perseverance was brought to work, and a huge mis-shapen mass upon the east side shews the explorers were successful." Unfortunately no inventory was published of its stores; and such will too generally be the case, so long as the possession of a metal ring or bracelet is liable to be hunted for by an official (like a kittywake by the Skoutie-allan) till the precious bait is disgorged. The law of treasure-trove fuses nearly all antiquities of gold or silver; they find their way to a watch-cobler, and thence to a crucible. It is a mere fiction to assert, that either Queen, Government, or nation can derive any pecuniary benefit from the few articles that are occasionally turned up; in fact, neither of these parties ever see them; and the only way to prevent their conversion is to let it be known that they are the property of those who find them, and that the lucky individual is to get the largest amount of sterling money that the articles will fetch in open market. The more they cost the purchaser, the greater will be the chance of their ultimate preservation.

Note a. Its elevation is marked upon the General Plan.

Such is the distribution of the antiquities in the immediate neighbourhood of Stenness, of which the writer, at the risk of being tedious, has endeavoured to render an exact account. Their written history, as may be supposed, is meagre enough. The Orkneyinga Saga, presumed to be compiled in the thirteenth century, does not mention or refer to Stenness. In the Saga of Olaf Trygvesson it is said, "Havard var pa 6 Steinsnessi i Rossey; par var fundi oc Bardagi peina Havards, oc ei langt ade Jarl fell, heiter nu Havards teigr," which my friend Professor Munch thus translates: "Havard was then at Stenness, in Rossey; there Havard and the other (Einar) met and fought, and in a short time the Earl fell, which (place) is now called Havard's teigr." Teigr is thus explained: Cultivated ground of indefinite size, inclosed within a turf or stone dyke, is a tun, or town-land. The tun is often occupied by several families, who annually re-divide by lot the arable land between them, and, for greater fairness, the good and bad land is divided into many small pieces or shares, and any of these is a teigr, and may be called after the present possessor, as Willie's teigr, or Magnus' teigr, &c. It is very probable that Earl Havard was buried beneath one of the Stenness tumuli.

The first direct notice of the stones of Stenness is in "Descriptio Insularum Orchadiarum anno 1529, per me Joan. Ben, ibidem colentem," where he says, "Stenhouse is another parish, where there is a great lake twenty-four miles in circumference. There, in a little hill near the lake, were found in a sepulchre the bones of a man, which indeed were joined, and were in length fourteen feet, as the reporter stated, and a coin was there found under the head of that dead man; and I, indeed, saw the sepulchre. There, near the lake, are high and broad stones, of the height of a spear, in circumference half-a-mile." The reporter seems to have been guilty of the very common fault of exaggeration.

In Wallace's History of Orkney, published in 1700, at p. 58, we find, "At Stennis, in the mainland, where the loch is narrowest, in the middle, having a causey of stones over it for a bridge, there is, at the south end of the bridge, a round, set about with high smooth stones or flags, about twenty feet high above ground, six feet broad, and each a foot or two thick. Betwixt that round and the bridge are two stones standing, with that same largeness with the rest, whereof one has a round hole in the midst of it; and at the other end of the bridge, about half-a-mile removed from it, is a large round, about one hundred and ten paces in diameter, set about with such stones as the former, but that some of them have fallen down; and at both east and west of this bigger round are two artificial (as it is thought) green mounds. Both these rounds are ditched about." There is a figure of one of these circles appended, but is purely imaginary.

In "A brief Description of Orkney, Zetland, Pightland Firth, and Caithness, by John Brand," published at Edinburgh in 1701, it is stated, "At the Loch of Stenness, in the mainland, in that part thereof where the loch is narrowest, both on the west and east side of the loch, there is a ditch, within which there is a circle of large and high stones erected. The larger round is on the west side, above 100 paces diameter. The stones, set about in form of a circle within a large ditch, are not all of a like quantity and size, though some of them, I think, are upwards of twenty feet high above ground, four or five feet broad, and a foot or two thick; some of which stones are fallen, but many of them are yet standing; between which there is not an equal distance, but many of them are about ten or twelve feet distant from each other. On the other side of the loch, over which we pass by a bridge laid in the manner of a street, the loch there being shallow, are two stones standing, of a like bigness with the rest, whereof one has a round hole in the midst of it; at a little distance from which stones there is another ditch, about half a mile from the former, but of a far less circumference, within which also there are some stones standing, something bigger than the other stones on the west side of the loch, in form of a semi-circle, I think, rather than of a circle, opening to the east, for I see no stones that have fallen there save one, which, when standing, did but complete the semi-circle. Both at the east and west end of the bigger round are two green mounts, which appear to be artificial; in one of which mounts were found, saith Mr. Wallace, nine fibula of silver, round, but opening at one place like to a horse-shoe."—p. 43

In vol. iii. of Arch. Scot, there is a rude woodcut from a drawing, and extracts from a description of the stones of Stenness, communicated by the Rev. Dr. Henry, in 1/84. In the drawing we have an amatory couple exchanging vows at the shrine of Odin, but unfortunately the Odin stone [Map] is drawn standing upon the east instead of the west side of the Stenness Ring. There are eight standing and two fallen stones in the Stenness Ring, which forms an exact semi-circle, and the cromlech is removed from the north side to what is intended to be the centre. Upon the cromlech is a kneeling damsel supplicating for the power to do all that is wanted from her by her future lord, while he is standing by, and seems to be rather intoxicated, but whether from love or wine is not to be determined from the drawing. I quote the following account, which I believe to be extremely exaggerated. "There was a custom among the lower class of people in this country, which has entirely subsided within these twenty or thirty years, when a party had agreed to marry, it was usual to repair to the Temple of the Moon, where the woman, in presence of the man, fell down on her knees and prayed the god Woden (for such was the name of the god whom they addressed on this occasion) that he would enable her to perform all the promises and obligations she had made and was to make to the young man present; after which they both went to the Temple of the Sun, where the man prayed in like manner before the woman. Then they repaired from this to the stone north-east of the semi-circular range; and, the man being on the one side and the woman on the other, they took hold of each other's right hand through the hole in it, and there swore to be constant and faithful to each other. This ceremony was held so very sacred in those times, that the person who dared to break the engagement made here was counted infamous, and excluded from society."—p. 119. In the description of the before-mentioned drawing, the Ring of Stenness is called "the semi-circular hof or temple of standing stones, dedicated to the moon,, where the rights of Odin were also celebrated:" but my witty friend, Mr. Clouston, is of opinion that it was only the lunatics who worshipped here. The Ring of Brogar is called "the Temple of the Sun:" unfortunately, the Ring of Bukan, which was of course the Temple of the Stars, seems to have escaped notice, or we might have learned of some more ante-nuptial ceremonies performed therein.

Principal Gordon, in "Remarks made in a Journey to the Orkney Islands"in 1781, gives the following sensible account of the Stenness antiquities. "From Kirkwall I went to Stromness, and in my way thither visited the semicircle and circle of stones near the Lake of Stenhouse. This lake is of fresh water, and runs into the sea at Stromness. It extends for about ten miles south-east; at Stenhouse is almost divided into two separate lakes by a neck of land, where the water is so shallow that it may be passed at any time, even when the tide flows.

"From this neck of land the lake runs north-west for about six miles, leaving an intermediate space of dry ground, which, from one-eighth of a mile, widens to about a mile towards the manse of Sandwick.

"The semicircle stands opposite to the place where the lake begins to wind to the north-west. The stones have been originally seven, four of which are still standing, and seem to be about fourteen feet high; one, however, is eighteen complete; their breadth about five feet; their thickness varies. This semicircle has been formed with some degree of art; for, were we to form it into a complete circle, the diameter would be one hundred and four feet, and, upon examination, the diameter of the semicircle as it was at first designated is exactly fifty-two, a clear proof that the planners of this semicircle were not unacquainted with mathematical proportions.

"At some distance from the semicircle to the right stands a stone by itself, eight feet high, three broad, and nine inches thick, with a round hole on the side next the lake. The original design of this hole was unknown till, about twenty years ago, it was discovered by the following circumstance: a young man had seduced a girl under promise of marriage, and she, proving with child, was deserted by him. The young man was called before the session; the elders were particularly severe. Being asked by the minister the cause of so much rigour, they answered, You do not know what a bad man this is, he has broke the promise of Odin. Being further asked what they meant by the promise of Odin, they put him in mind of the stone of Stenhouse with a round hole in it, and added that it was customary when promises were made for the contracting parties to join hands through the hole, and the promises so made were called the promises of Odin.

"The complete circle stands upon the intermediate space betwixt the two branches of the lake, and this space or promontory, being a rising ground which forms at last into a plain of some extent, is seen at a considerable distance. There are sixteen of the stones standing, eight more are fallen to the ground; the original number is uncertain. Their height differs from nine to fourteen feet above the ground. The diameter of the circle is 366 feet. Round the circle is a ditch thirty-five feet broad, and from nine to fourteen feet deep: round the ditch, at unequal distances from one another, are eight small artificial eminences. The entrance is from the east, with an opening of equal size to the west. The altar stood without the circle to the south-east: to the left of the circle looking eastward, you perceive a solitary stone, and two or three more such in a direct line with it on to the semicircle. There is no inscription upon any of the stones either of the circle or semicircle.

"Different reasons have been assigned by different people for the circular and semicircular form of the Scandinaviana temples, for such they certainly have been, as appears from the explication given above of what is called in Orkney the promise of Odin. Some have pretended that the semicircular temple was in honour of the moon, and the circular one in honour of the sun; others that the semicircle and circle were emblems of the different phases of the moon. Pocock bishop of Ossory, who visited Orkney several years ago, found out in the different stones composing the circle and semicircle a very minute astronomical description of the various motions of the sun, moon, and planets, but these fancies have no foundation, as far as I could see, either in the arrangement of the stones or in the Scandinavian mythology. It does not appear from the Edda of Iceland, where we have a very full account of the Scandinavian divinities, that either the sun, moon, or stars had any place among them. 1 do not pretend to give a better reason for the circular or semicircular shape of these temples than what has been given by others. Indeed, it is impossible to give any good one at this distance of time; however, we see that in different nations the circular shape was a favourite one in building temples; witness the Rotunda at Rome, and many others on a smaller scale in other parts of the heathen world."

Note a. I need scarcely remark, that there is not the slightest evidence of these circles having been made by the Northmen.

It may be expected that the writer of these remarks should offer some conjecture concerning the age and purpose of these interesting monuments of antiquity, and indeed it would be difficult after having been so long engaged with them to avoid forming a theory on the subject; and it may at once be stated that he considers the whole of them to have,been originally intended for sepulchral monuments, though they may subsequently have been used as places for council, feasting, or sacrifice. The cromlech within the Ring of Stenness is conclusive in that instance; and, though nothing can be seen within the Ring of Brogar to determine the purpose of its erection, the Ring of Bukan, which is evidently of the same genus, if not of the same species, contains indications which are now constantly recognised as sepulchral. These monuments have undoubtedly been erected by the same race of people who have made similar ones in other parts of Britain; their age is consequently nearly the same as that of Stonehenge, Avebury, &c, but more learned antiquaries must decide upon the exact epoch. That the Orcadian circles were already existing on the introduction of Christianity will be readily admitted, though this was as early as the middle of the sixth century, when St. Colomba sent Cormac, one of his disciples, to these islands; and though a period of paganism ensued after the conquest by Harald Harfagre in A.D. 875, to the forced conversion of the second Sigurd, about A.D. 998 (which is but one hundred and twenty-three years), there is nothing in the northern annals to lead us to the opinion of their having been constructed in that interval.

This closes the account of the Stenness antiquities; but it will be proper to notice here some interesting remains that were I believe first described by the Rev. C. Clouston, in his Statistical Account of Sandwick. One of these is a cromlech, known by the name of the Stones of Veu (Ve signifying holy or sacred), situated about half a mile to the southward of the manse upon the moor. The cromlech, which has been overthrown, but not otherwise destroyed, is formed by four square short pillars, three feet in height, supporting a square slab (5 ft. 10 in. x 4 ft. 9 in. X 1 ft. 0 in). Upon one side there lies a smaller square slab; but whether it was originally placed on the top of the other, or formed a small supplemental cromlech like that represented in plate i, fig. 10, of Akerman's Archaeological Index, is not to be determined.

Another ruin of a cromlech of a far more complex character, called Holy Kirk, stands upon the brow of Vestrafiold, which Mr. Clouston describes "as a curious collection of large and ancient stones; and a gentleman residing in that neighbourhood recollects one of them, now prostrate, supported by those that are still perpendicular." It would be well if this gentleman would put his recollection upon record, for Mr W. Wall and myself puzzled for more than an hour over these remains without being able to divine its plan: there appeared to have been either two or three covers originally.

A very interesting but obscure remnant of antiquity exists upon the south foot of Vestrafiold, which I believe must be classed with Celtic remains; it is a large irregular inclosure, approaching to a square in outline, and fenced by large flags where they have not been carried away. It is stated to be 800 yards in circumference. A water-course runs through the area, and there are indications of interior sub-division by ranges of flags. No reason can be detected for choosing such a site; the greater part of the area I should imagine has always been very swampy; on the north-west side the line of demarcation runs up and along a rather steep brae (perhaps twenty feet higher than the average level). The great size of the inclosing flags, uselessness for keeping out cattle, &c, and the barren piece of land, which has never been of any agricultural value, are the proofs of its antiquity, and I commend this inclosure to the notice of practical antiquaries. The Dwarfie Stone of Hoy, of which there is a drawing and description in Barry's History of Orkney, is probably a sepulchral monument of the Pictish period; and I am informed by Professor Munch that there is a romantic story in the elder Edda, which occurs in Hoy, but the name is so commonly given to high islands by the Northmen, that we cannot be certain that it refers to one of the Orcadian group.

The round tower and church of Egilsey are in all probability the erection of the christianized Picts; and at the Brough of Birsa the foundation of such another church and cylindrical tower are to be seen. The Brough of Deerness is also a station of great antiquity; and in several of the islands there are the ruins of old churches which would, I believe, be of considerable interest to the ecclesiastical antiquary.

Archaeologia Volume 34 1851 XIII Orkney Chapter III

WE have now to consider a Class of Antiquities deserving much greater attention than they have hitherto received. I allude to those structures which the general traditions of the North of Scotland have ascribed to the Picts. These may be divided into Picts Castles and Picts Houses; but, though the first term may be allowed to pass without much argument, the propriety of the second may by some be considered to be hardly substantiated by the known facts.

The Pictish Broughs may be generally described as circular towers of sixty feet in diameter, and forty or fifty in height, and are either formed of one cylindrical wall of great thickness in which small chambers or cells are left in the interior of the wall, or of two concentric walls, the interspace being formed by flagstones into circular galleries, to which there is a communication by means of a winding staircase. Much information concerning these broughs may be gathered from Pennant's Scottish Tour, Cordiner's Remarkable Ruins of North Britain, Hibbert's Shetland, &c.; but I shall limit my remarks to the little that is known of them in Orkney.

In Orkney the site of a Picts castle may be generally known by the name of "Brough" being bestowed upon the place, and a grassy hillock most frequently points out the exact spot, where it has stood; this term does not however apply exclusively to an artificial elevation, but includes every place of defence. The prefix "bur" is a contraction of "brough," as Burwick in South Ronaldsey, and in Sandwick, where the ruin of the brough at either place may be seen. Burra, formerly Borgarey, means the castle island; Burgher in Evie is the place of the castle; and at Burroston, in Shapinsey, Mr. Balfour informs me, are the remains of extensive entrenchments and fortifications. The position of the Pictish broughs is generally not peculiar for natural strength; they are either built along the sea-shore, as in Evie, &c. &c. or upon a small island or point in a lake; but we do not find them upon those natural defences which are seen along the coast, where a small piece of land is separated by a chasm from the main, as at the Broughs of Deerness, Biggin, &c, or upon an easily defensible peninsula, as at Burrow (Brough) Head in Stronsev, though at all these places the remains of a wall or a ditch may be traced upon the landward side.