Charges

Charges is in Terms.

Battering Ram

Bertie Arms. Argent, three battering rams, barwise in pale proper, armed and garnished azure. Source.

Bertie Arms. Argent, three battering rams, barwise in pale proper, armed and garnished azure. Source.

Billet

Billet. A small rectangle.

Broom Plant

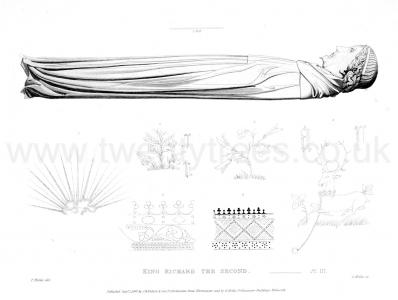

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. I will now proceed to notice in succession the several devices with which the robes of the Effigies before us are adorned. The robes of the King are powdered or strewn with three badges, the White Hart, the Broom Plant, and the Rising Sun. Among them are intermixed the letters R and A, the initials of Richard and Anne. The borders of the robes are ornamented with elegant patterns minutely delineated, the principal being a running scroll of the Broom-plant; at the foot are two rows of ermine spots, and the hood is also lined with ermine, but the inner sides of the mantle are plain. The badges on the mantle are interwoven with running lines of flowers or small leaves, in a manner so nearly resembling a curious painting of Richard the Second which is now preserved in the Earl of Pembroke's collection at Wilton, that, before I proceed further, I shall take some notice of that picture.

Broom Cods

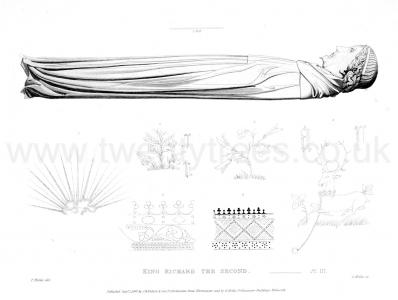

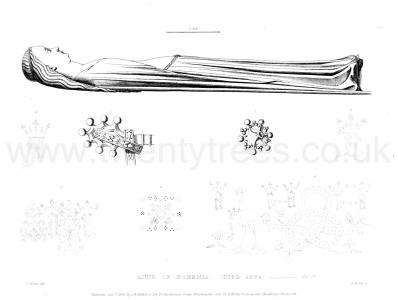

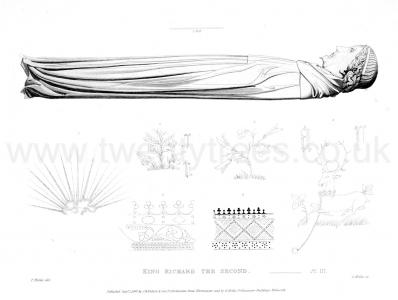

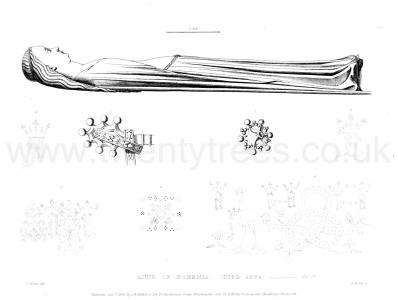

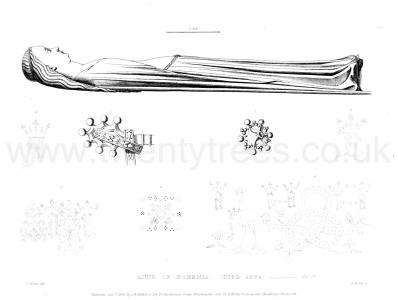

Monumental Effigies. King Richard II and his Queen Anne of Bohemia. Remarkable decoration of White Harts, sunbursts, broom cods on his clothes, as well as the initials A and R. Similarly, her clothes are decorated with the Ostriches with a nail in the beak, a symbol of Bohemia, from which the ostrich feathers, and entwined knots. Note his beard as also seen in portraits.

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. It is painted on two tablets, and Hollar engraved it in two plates in the year 1639; but the two when viewed together form but one design. The King is kneeling in prayer to the Virgin and her Son; behind him stand the three saints, John the Baptist, Edward the Confessor, and Edmund the King. Behind and around the Virgin are eleven angels. King Richard is here attired in a gown powdered with White Harts, which are interlaced with Broom-cods running in the same manner as the interlacing foliage on the mantle of his Effigy. He wears round his neck a collar of Broom-cods; and on his left shoulder is his badge of the White Hart. But what is more extraordinary is, that each of the eleven angels wears a similar collar and a similar badge. It must be remarked that the pendant to the collar in front, in every case, is formed of two of the Broom-cods only; and that the King, as well as the angels, wears the White Hart, as a badge, on his shoulder, not as a pendant to the collar, as was misapprehended by Anstisg. It was this picture which furnished a subject of discussion to Walpole in connexion with the alleged discovery of oil-painting by Van Eyckh; but it was proved to be painted in water-colours, on an examination by T. Phillips, Esq. R.A. as is noticed in Britton's Beauties of Wiltshire. It formerly belonged to the Royal Collection, but is said to have been given away by King James the Second to Lord Castlemaine, about the time he went Ambassador to Rome, after whose death it was purchased by the Earl of Pembroke, and added to the Collection at Wilton.

Note g. Register of the Order of the Garter, vol. i. p. 112; and also in p. 110. Anstis was here writing of collars, and he did not sufficiently bear in mind that the badge, stigma, mark, sign, or cognizance was another thing. He followed the verses under Hollar's print, in which it is erroneously said, "Pendulus est albus cervus," &c. Anstis, in turn, is followed by Mr. Beltz, who states that the White Hart was "pendent from a collar," in his Notices of Collars of the King's Livery, Retrospective Review, new series, vol. ii. p. 501.

Note h. In reference to this subject, see a paper by the present writer in the Gentleman's Magazine for Nov. 1840, vol. xiv. p. 489, relative to a picture in the Duke of Devonshire's villa at Chiswick, which was assigned by Walpole to Van Eyck, and supposed to represent the family of Lord de Clifford, but regarding which, Mr. Waagen has pronounced that "Jan Van Eyck is quite out of the question," and which is shown (ubi supra) to be the portraits of Sir John Donne and his wife Elizabeth, sister to Lord Hastings, temp. Edw. IV. They wear the collar of that King's livery, formed of alternate roses and suns, with a white lion sejant as a pendant.

Buckles

Jerningham Arms. Argent, three buckles lozengy gules. Source.

Jerningham Arms. Argent, three buckles lozengy gules. Source.

Leslie Arms. Argent, on a bend azure three buckles or. Source.

Leslie Arms. Argent, on a bend azure three buckles or. Source.

John Stewart of Darnley 1st Count Évreux 1380 1429 Arms.

John Stewart of Darnley 1st Count Évreux 1380 1429 Arms.  Capet Arms within a bordure gules charged with eight buckles or. Awarded in 1427 by King Charles VII of France. Source.

Capet Arms within a bordure gules charged with eight buckles or. Awarded in 1427 by King Charles VII of France. Source.

Castle

Caerleon Arms. Gules three castles argent. Source.

Caerleon Arms. Gules three castles argent. Source.

Portugal 1248 Arms.

Portugal 1248 Arms.  Portugal Arms a bordure gules charged with fourteen golden triple-towered castles. Source.

Portugal Arms a bordure gules charged with fourteen golden triple-towered castles. Source.

Portugal 1385 Arms. Argent, in Cross azure each charged with five plates in saltire charged with ten golden triple-towered castles and four fleur de lys in cross vert, Source.

Portugal 1385 Arms. Argent, in Cross azure each charged with five plates in saltire charged with ten golden triple-towered castles and four fleur de lys in cross vert, Source.

Castile Arms. Gules a castle or.

Castile Arms. Gules a castle or.

Chaplet

Chaplet. A garland typically with four leaves.

Chronica Majora. 19 Jan 1236. There were assembled at the king's (age 28) nuptial festivities such a host of nobles of both sexes, such numbers of religious men, such crowds of the populace, and such a variety of actors, that London, with its capacious bosom, could scarcely contain them. The whole city was ornamented with flags and banners, chaplets and hangings, candles and lamps, and with wonderful devices and extraordinary representations, and all the roads were cleansed from mud and dirt, sticks, and everything offensive. The citizens, too, went out to meet the king (age 28) and queen (age 13), dressed out in their ornaments, and vied with each other in trying the speed of their horses. On the same day, when they left the city for Westminster, to perform the duties of butler to the king (which office belonged to them by right of old, at the coronation), they proceeded thither dressed in silk garments, with mantles worked in gold, and with costly changes of raiment, mounted on valuable horses, glittering with new bits and saddles, and riding in troops arranged in order. They carried with them three hundred and sixty gold and silver cups, preceded by the king's trumpeters and with horns sounding, so that such a wonderful novelty struck all who beheld it with astonishment. The archbishop of Canterbury (age 61), by the right especially belonging to him, performed the duty of crowning, with the usual solemnities, the bishop of London assisting him as a dean, the other bishops taking their stations according to their rank. In the same way all the abbats, at the head of whom, as was his right, was the abbat of St. Alban's (for as the Protomartyr of England, B. Alban, was the chief of all the martyrs of England, so also was his abbat the chief of all the abbats in rank and dignity), as the authentic privileges of that church set forth. The nobles, too, performed the duties, which, by ancient right and custom, pertained to them at the coronations of kings. In like manner some of the inhabitants of certain cities discharged certain duties which belonged to them by right of their ancestors. The earl of Chester (age 29) carried the sword of St. Edward, which was called "Curtein", before the king, as a sign that he was earl of the palace, and had by right the power of restraining the king if he should commit an error. The earl was attended by the constable of Chester (age 44), and kept the people away with a wand when they pressed forward in a disorderly way. The grand marshal of England, the earl of Pembroke (age 39), carried a wand before the king and cleared the way before him both, in the church and in the banquet-hall, and arranged the banquet and the guests at table. The Wardens of the Cinque Ports carried the pall over the king, supported by four spears, but the claim to this duty was not altogether undisputed. The earl of Leicester (age 28) supplied the king with water in basins to wash before his meal; the Earl Warrenne performed the duty of king's Cupbearer, supplying the place of the earl of Arundel, because the latter was a youth and not as yet made a belted knight. Master Michael Belet was butler ex officio; the earl of Hereford (age 32) performed the duties of marshal of the king's household, and William Beauchamp (age 51) held the station of almoner. The justiciary of the forests arranged the drinking cups on the table at the king's right hand, although he met with some opposition, which however fell to the ground. The citizens of London passed the wine about in all directions, in costly cups, and those of Winchester superintended the cooking of the feast; the rest, according to the ancient statutes, filled their separate stations, or made their claims to do so. And in order that the nuptial festivities might not be clouded by any disputes, saving the right of any one, many things were put up with for the time which they left for decision at a more favourable opportunity. The office of chancellor of England, and all the offices connected with the king, are ordained and assized in the Exchequer. Therefore the chancellor, the chamberlain, the marshal, and the constable, by right of their office, took their seats there, as also did the barons, according to the date of their creation, in the city of London, whereby they each knew his own place. The ceremony was splendid, with the gay dresses of the clergy and knights who were present. The abbat of Westminster sprinkled the holy water, and the treasurer, acting the part of sub-dean, carried the Paten. Why should I describe all those persons who reverently ministered in the church to God as was their duty? Why describe the abundance of meats and dishes on the table & the quantity of venison, the variety of fish, the joyous sounds of the glee-men, and the gaiety of the waiters? Whatever the world could afford to create pleasure and magnificence was there brought together from every quarter.

Clotworthy Arms. Azure, a chevron ermine between three chaplets or. Source.

Clotworthy Arms. Azure, a chevron ermine between three chaplets or. Source.

Morrison Arms. Or, on a chief gules three chaplets of the first. Source.

Morrison Arms. Or, on a chief gules three chaplets of the first. Source.

Chequy

Acland Arms. Chequy argent and sable, a fess gules. Source.

Acland Arms. Chequy argent and sable, a fess gules. Source.

Beaumont Arms. Chequy or and azure a chevron ermine. Source.

Beaumont Arms. Chequy or and azure a chevron ermine. Source.

Chichester Arms. Chequy or and gules, a chief vair. Source.

Chichester Arms. Chequy or and gules, a chief vair. Source.

Clifford Arms. Chequy or and azure, a fess gules. Source.

Clifford Arms. Chequy or and azure, a fess gules. Source.

Fitzwilliam Arms. Chequy gules and argent. Source.

Fitzwilliam Arms. Chequy gules and argent. Source.

Warenne Arms. Chequy or and azure. Source.

Warenne Arms. Chequy or and azure. Source.

Chevronel

Bagot Arms. Ermine, two chevronels azure. Source.

Bagot Arms. Ermine, two chevronels azure. Source.

Cookes Arms. Argent, two chevronels between six martlets 3, 2 and 1 gules. Source.

Cookes Arms. Argent, two chevronels between six martlets 3, 2 and 1 gules. Source.

Hornby Arms. Or, two chevronels between three bugle-horns sable stringed gules on a chief of the second as many eagle's legs erased of the first. Source.

Hornby Arms. Or, two chevronels between three bugle-horns sable stringed gules on a chief of the second as many eagle's legs erased of the first. Source.

Monson Arms. Or two chevronels gules. Source.

Monson Arms. Or two chevronels gules. Source.

Strutt Arms. Per Pale sable and azure, two chevronels engrailed, between three cross crosslets fitchy or. Source.

Strutt Arms. Per Pale sable and azure, two chevronels engrailed, between three cross crosslets fitchy or. Source.

Clarion

Clarion. Unclear as to origin. Possibly a spear rest?.

Crancelin

Crancelin. A Crown.

Delve

Delve. A sod of earth.

Delves Arms. Argent, a chevron gules fretty or between three delves sable. Source.

Delves Arms. Argent, a chevron gules fretty or between three delves sable. Source.

Falcon and Fetterlock

Around 1460. The Falcon and Fetterlock Yorkist emblem at St Mary and All Saints Church, Fotheringhay [Map].

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. In 1375 the Black Prince bequeathed to his son Richard his hangings for a hall, embroidered with mermen, and a border of red and black impaled, embroidered with swans having lady's heads, and ostrich feathers: to his wife, the Princess, he bequeathed a hall of red worsted, embroidered with eagles and griffins, with a border of swans having lady's heads; and to Mons. Aleyne Cheyne a bed of camoca, powdered with blue eagles. In 1385, Joan Princess of Wales bequeathed "To my dear son, the King, my new bed of red velvet, embroidered with ostrich feathers of silver, and heads of leopards of gold, with boughs and leaves issuing out of their mouths." Edward, [Note. Edward assumed to be a mistake for Edward?] Earl of March, in 1380, bequeathed to his son and heir, "our large bed of black satin, embroidered with white lions and gold roses, with escutcheons of the arms of Mortimer and Ulster;" and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, in 1397, bequeathed to the altar of St. Paul's cathedral "his great bed of cloth of gold, the champepiers powdered with golden roses, placed upon pipes of gold, and in each pipe two white ostrich feathers;" and again, to his daughter the Duchess of Exeter, his "white bed of silk, with blue eagles displayed." In 1415, Edward, Duke of York, bequeathed to his wife "my bed of feathers and leopards, with the furniture appertaining to the same; also my white and red tapestry of garters, fetter-locks, and falconsb".

Note b. Nichols's Royal and Noble Wills. Nicolas's Testamenta Vetusta.

Fer de Moline

Fer de Moline. A mill wheel.

Fers de Moline

Fers de Moline. A mill wheel.

Turner Baronets Arms. Sable, a chevron ermine between three fers de moline or on a chief argent a lion passant gules. Source.

Turner Baronets Arms. Sable, a chevron ermine between three fers de moline or on a chief argent a lion passant gules. Source.

Flaunche

Flaunche. A flank, sometimes flasque. Always in pairs.

Flowers

Barbed and Seeded Proper

Boscawen Arms. Ermine, a rose gules barbed and seeded proper. Source.

Boscawen Arms. Ermine, a rose gules barbed and seeded proper. Source.

Duke Montrose Arms. Quarterly, 1&4

Duke Montrose Arms. Quarterly, 1&4  Graham Arms 2&3 Argent three roses gules barbed and seeded proper (Montrose).

Graham Arms 2&3 Argent three roses gules barbed and seeded proper (Montrose).

Knollys Arms. Gules, on a chevron argent, three roses gules, barbed and seeded proper. Source.

Knollys Arms. Gules, on a chevron argent, three roses gules, barbed and seeded proper. Source.

Lily

Fleur de lys. The Lily. Typically representing the House of France.

Primrose

Earl Roseberry Arms. Quarterly, 1&4 vert, three primroses within a double tressure flory counter-flory or (for Primrose); 2&3 argent, a lion rampant double queued sable (for Cressy). Source.

Earl Roseberry Arms. Quarterly, 1&4 vert, three primroses within a double tressure flory counter-flory or (for Primrose); 2&3 argent, a lion rampant double queued sable (for Cressy). Source.

Fountain

Stourton Arms. Sable, a bend or between six fountains. Source.

Stourton Arms. Sable, a bend or between six fountains. Source.

Fret

Cosin Arms. Azure, a fret or.

Cosin Arms. Azure, a fret or.

Despencer Arms. Quarterly 1&4: Argent, 2&3: Gules, a fret or, over all a bend sable. Source.

Despencer Arms. Quarterly 1&4: Argent, 2&3: Gules, a fret or, over all a bend sable. Source.

Harrington Arms. Argent, fret sable.

Harrington Arms. Argent, fret sable.

Spencer Arms. Quarterly 1&4: Argent, 2&3: Gules, a fret or, over all a bend sable.

Spencer Arms. Quarterly 1&4: Argent, 2&3: Gules, a fret or, over all a bend sable.

Tollemache Arms. Argent, a fret sable.

Tollemache Arms. Argent, a fret sable.

Verdun Arms. Or, a fret gules.

Verdun Arms. Or, a fret gules.

Fusil

Fusil. An elongated lozenge.

Garb

Garb. A wheat-sheaf. When a sheaf of any other grain is borne the name of the grain must be expressed. When the stalks are of one tincture and the ears of another, the term eared must be used.

Cholmondeley Arms. Gules, in chief two esquire's helmets argent in base a garb or. Source.

Cholmondeley Arms. Gules, in chief two esquire's helmets argent in base a garb or. Source.

Grosvenor Arms. Azure a garb or. Source.

Grosvenor Arms. Azure a garb or. Source.

Gemelles

Gemelles. Twin narrow horizontal lines.

Badlesmere Arms. Argent, a fess between two gemelles gules. Source.

Badlesmere Arms. Argent, a fess between two gemelles gules. Source.

Throckmorton Arms. Gules, on a chevron argent three bars gemelles sable. Source.

Throckmorton Arms. Gules, on a chevron argent three bars gemelles sable. Source.

Grozing Irons

Grozing Irons. A pair of pliers for clipping the edges of pieces of glass.

Keilway Arms. Argent, two grozing irons in saltire sable between four Kelway pears proper. An example of Canting arms Kelway Pear = Keilway. Source

Keilway Arms. Argent, two grozing irons in saltire sable between four Kelway pears proper. An example of Canting arms Kelway Pear = Keilway. Source

Heart

Brunswick Luneburg Arms. Per pale, I gules two lions passant guardant or (for Brunswick), II or a semy of hearts gules a lion rampant azure (for Lunenburg).

Brunswick Luneburg Arms. Per pale, I gules two lions passant guardant or (for Brunswick), II or a semy of hearts gules a lion rampant azure (for Lunenburg).

Earl Douglas Arms. NO IMAGE a heart gules imperially crowned or.

Earl Douglas Arms. NO IMAGE a heart gules imperially crowned or.

Lozenge

Lozenge. Lozenges are frequently conjoined in the form of ordinaries, and in all such cases the number of the lozenges should be given.

Feilding Arms. Argent, on a fess azure three lozenges or. Source.

Feilding Arms. Argent, on a fess azure three lozenges or. Source.

Joicey Arms. Argent three lozenges Sable within two bendlets invected gules between two miners' picks in bend proper. Source.

Joicey Arms. Argent three lozenges Sable within two bendlets invected gules between two miners' picks in bend proper. Source.

Mascle

Mascle is a diamond shape.

Spring of Lavenham Arms. Argent, a chevron engrailed between three mascles gules. Source.

Spring of Lavenham Arms. Argent, a chevron engrailed between three mascles gules. Source.

Maunch

Maunch. A sleeve of the type typically worn in the 13th and 14th Centuries.

Introduction. Thus it also appears probable that the metallic colours of heraldry had their rise in the actual use of the precious metals by the infidels, in the gorgeous distinctions assumed by them for their armoura.

Note a. How many distinctive bearings were suggested by garments, arms, or implements, which must have been familiar to the warriors of the crusades: manches, vair, flanches, minever, swords, arbalists, bows, lances, arrows, pheons (barbed heads for missiles), battering-rams, water-budgets, &c.

Calthorpe Arms. Ermine, a maunch gules. Source.

Calthorpe Arms. Ermine, a maunch gules. Source.

Conyers Arms. Azure, a maunch or. Source.

Conyers Arms. Azure, a maunch or. Source.

Hastings Arms. Argent, a maunch gules. Source.

Hastings Arms. Argent, a maunch gules. Source.

Tosny Arms. Argent, a maunch. Source.

Tosny Arms. Argent, a maunch. Source.

Morion Cap

Morion Cap. A cap made of steel usually worn by foot soldiers.

Ostrich Feathers

Monumental Effigies. King Richard II and his Queen Anne of Bohemia. Remarkable decoration of White Harts, sunbursts, broom cods on his clothes, as well as the initials A and R. Similarly, her clothes are decorated with the Ostriches with a nail in the beak, a symbol of Bohemia, from which the ostrich feathers, and entwined knots. Note his beard as also seen in portraits.

Letters 1536. Vienna Archives. 284. Death and Burial of Katharine of Arragon.

The good Queen (deceased) died in a few days, of God knows what illness, on Friday, 7 Jan. 1536. Next day her body was taken into the Privy Chamber and placed under the canopy of State (sous le dhoussier et drapt destat), where it rested seven days, without any other solemnity than four flambeaux continually burning. During this time a leaden coffin was prepared, in which the body was enclosed on Saturday, the 15th, and borne to the chapel. The vigils of the dead were said the same day, and next day one mass and no more, without any other light than six torches of rosin. On Sunday, the 16th, the body was removed again into the Privy Chamber, where it remained till Saturday following. Meanwhile an "estalage," which we call a chapelle ardente, was arranged, with 56 wax candles in all, and the house hung with two breadths of the lesser frieze of the country. On Saturday, the 22nd, it was again brought to the chapel, and remained until the masses of Thursday following, during which time solemn masses were said in the manner of the country, at which there assisted by turns as principals the Duchess of Suffolk (age 16), the Countess of Worcester (age 34), the young Countess of Oxford (age 18), the Countess of Surrey (age 19), and Baronesses Howard (age 21), Willoughby (age 24), Bray, and Gascon (sic).

25 Jan 1536. On Tuesday1 following, as they were beginning mass, four banners of crimson taffeta were brought, two of which bore the arms of the Queen, one those of England, with three "lambeaulx blancs," which they say are of Prince Arthur; the fourth had the two, viz., of Spain and England, together. There were also four great golden [standards]. On one was painted the Trinity, on the second Our Lady, on the third St. Katharine, and on the fourth St. George; and by the side of these representations the said arms were depicted in the above order; and in like manner the said arms were simply, and without gilding (? dourance), painted and set over all the house, and above them a simple crown, distinguished from that of the kingdom which is closed. On Wednesday after the robes of the Queen's 10 ladies were completed, who had not till then made any mourning, except with kerchiefs on their heads and old robes. This day, at dinner, the countess of Surrey held state, who at the vigils after dinner was chief mourner. On Thursday, after mass, which was no less solemn than the vigils of the day before, the body was carried from the chapel and put on a waggon, to be conveyed not to one of the convents of the Observant Friars, as the Queen had desired before her death, but at the pleasure of the King, her husband, to the Benedictine Abbey of Peterborough, and they departed in the following order:—First, 16 priests or clergymen in surplices went on horseback, without saying a word, having a gilded laten cross borne before them; after them several gentlemen, of whom there were only two of the house, "et le demeurant estoient tous emprouvez," and after them followed the maître d'hotel and chamberlain, with their rods of office in their hands; and, to keep them in order, went by their sides 9 or 10 heralds, with mourning hoods and wearing their coats of arms; after them followed 50 servants of the aforesaid gentlemen, bearing torches and "bâtons allumés," which lasted but a short time, and in the middle of them was drawn a waggon, upon which the body was drawn by six horses all covered with black cloth to the ground. The said waggon was covered with black velvet, in the midst of which was a great silver cross; and within, as one looked upon the corpse, was stretched a cloth of gold frieze with a cross of crimson velvet, and before and behind the said waggon stood two gentlemen ushers with mourning hoods looking into the waggon, round which the said four banners were carried by four heralds and the standards with the representations by four gentlemen. Then followed seven ladies, as chief mourners, upon hackneys, that of the first being harnessed with black velvet and the others with black cloth. After which ladies followed the waggon of the Queen's gentlemen; and after them, on hackneys, came nine ladies, wives of knights. Then followed the waggon of the Queen's chambermaids; then her maids to the number of 36, and in their wake followed certain servants on horseback.

In this order the royal corpse was conducted for nine miles of the country, i.e., three French leagues, as far as the abbey of Sautry [Map], where the abbot and his monks received it and placed it under a canopy in the choir of the church, under an "estalage" prepared for it, which contained 408 candles, which burned during the vigils that day and next day at mass. Next day a solemn mass was chanted in the said abbey of Sautry [Map], by the Bishop of Ely, during which in the middle of the church 48 torches of rosin were carried by as many poor men, with mourning hoods and garments. After mass the body was borne in the same order to the abbey of Peterborough, where at the door of the church it was honorably received by the bishops of Lincoln, Ely, and Rochester, the Abbot of the place, and the abbots of Ramsey, Crolain (Crowland), Tournan (Thorney), Walden and Thaem (Tame), who, wearing their mitres and hoods, accompanied it in procession till it was placed under the chapelle ardente which was prepared for it there, upon eight pillars of beautiful fashion and roundness, upon which were placed about 1,000 candles, both little and middle-sized, and round about the said chapel 18 banners waved, of which one bore the arms of the Emperor, a second those of England, with those of the King's mother, prince Arthur, the Queen of Portugal, sister of the deceased, Spain, Arragon, and Sicily, and those of Spain and England with three "lambeaulx," those of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, who married the daughter of Peter the Cruel, viz., "le joux des beufz," the bundle of Abbot of arrows, the pomegranate (granade), the lion and the greyhound. Likewise there were a great number of little pennons, in which were portrayed the devices of king Ferdinand, father of the deceased, and of herself; and round about the said chapel, in great gold letters was written, as the device of the said good lady, "Humble et loyale." Solemn vigils were said that day, and on the morrow the three masses by three bishops: the first by the Bishop of Rochester, with the Abbot of Thame as deacon, and the Abbot of Walden as sub-deacon; the second by the Bishop of Ely, with the Abbot of Tournay (Thorney) as deacon, and the Abbot of Peterborough as sub-deacon; the third by the Bishop of Lincoln (age 63), with the Bishop of Llandaff as deacon, and that of Ely as sub-deacon; the other bishops and abbots aforesaid assisting at the said masses in their pontificals, so the ceremony was very sumptuous. The chief mourner was lady Eleanor (age 17), daughter of the Duke of Suffolk (age 52) and the French Queen, and niece of King Henry, widower now of the said good Queen. She was conducted to the offering by the Comptroller and Mr. Gust (Gostwick), new receiver of the moneys the King takes from the Church. Immediately after the offering was completed the Bishop of Rochester preached the same as all the preachers of England for two years have not ceased to preach, viz., against the power of the Pope, whom they call Bishop of Rome, and against the marriage of the said good Queen and the King, alleging against all truth that in the hour of death she acknowledged she had not been Queen of England. I say against all truth, because at that hour she ordered a writing to be made in her name addressed to the King as her husband, and to the ambassador of the Emperor, her nephew, which she signed with these words—Katharine, Queen of England—commending her ladies and servants to the favor of the said ambassador. At the end of the mass all the mourning ladies offered in the hands of the heralds each three ells in three pieces of cloth of gold which were upon the body, and of this "accoutrements" will be made for the chapel where the annual service will be performed for her. After the mass the body was buried in a grave at the lowest step of the high altar, over which they put a simple black cloth. In this manner was celebrated the funeral of her who for 27 years has been true Queen of England, whose holy soul, as every one must believe, is in eternal rest, after worldly misery borne by her with such patience that there is little need to pray God for her; to whom, nevertheless, we ought incessantly to address prayers for the weal (salut) of her living image whom she has left to us, the most virtuous Princess her daughter, that He may comfort her in her great and infinite adversities, and give her a husband to his pleasure, &c. Fr., from a modern copy, pp. 6.

Note 1. This would be Tuesday, 1 Feb., if the chronology were strict; but the latest Tuesday that can be intended is 25 Jan.

Effigy of Edward, the Black Prince. Various reasons have been assigned for Edward's bearing the surname of the Black Prince; the most generally received, and perhaps the best entitled to credit, is that it arose from his wearing black armour. A circumstance which may throw some light on this point, and correct an error in another particular, appears to have been entirely overlooked. The three Ostrich Feathers within the Coronet, as at present borne, is generally understood to have been the Cognizance of the Black Prince, but on strict investigation, although his Will, his Seals, and his Tomb, give the most minute evidence on the subject, there exists no authority whatever for this disposition of the Ostrich Feathers. We are told that after the battle of Cressy, the banner of John, the old and blind King of Bohemia, there slain, was found in the field; upon it was wrought—sable, three ostrich feathers, with the motto Ich Dien; which cognizance, in memory of the day, was adopted by Prince Edward. By what authority this account is supported, is uncertain; but the German words Ich Dien and Houmont on the tomb, seem to give it probability. Although there is no farther proof that the feathers were borne by the King of Bohemia, yet it is not a little remarkable, that his granddaughter Anne, bore an ostrich as her Badge. Instead of the feathers either being worn within the coronet, or as a crest, the evidence on the tomb is contrary, they are borne as a coat, on an escutcheon. From the subjoined extract of the Prince's will, in the passage describing the man and horse, armed and covered with the badges, it is clear that the former bore them on his surcoat, and the latter on the bardinga. We cannot, therefore, be surprised, if the Prince of Wales wore such sable trappings, (which must be interred from the extract alluded to,) that he should have received the surname of the Black Prince. It may be necessary to remark, that the first notice of this surname occurs soon after the battle of Cressy.

Note a. There is a curious coincidence, bearing strong evidence on this point, in a beautiful manuscript, containing in French verse, an account of the iatter part of the life of Richard II written and illuminated by one who was an eyewitness to what he describes. In the second illumination Richard II is represented knighting Henry of Monmouth. The king is on horseback, in armour, his surcoat and the barding of the horse is powdered with ostrich feathers, and above him appears a pennon emblazoned in like manner. BibF. Harl".

Edward the Black Prince leaves to his son Richard in his will, "a blue vestment embroidered with gold roses and ostrich feathers." The feathers, and other devices of the Black Prince are also alluded to in the two following passages of the said Will:—"We give and devise our Hall of Ostrich Feathers of black Tapestry with a red border wrought with Swans with Ladies Heads, that is to say, a back piece, eight pieces for the sides and two for the Benches to the said Church of Canterbury, &c., &c."-" Item, we give and devise to our said son the Hall of Arras of the deeds of Saladyn, and also the Hall of worsted embroidered with Mermaids of the Sea, and the border paly red and black, embroidered with swans with Ladies Heads and Ostrich Feathers."

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. In 1375 the Black Prince bequeathed to his son Richard his hangings for a hall, embroidered with mermen, and a border of red and black impaled, embroidered with swans having lady's heads, and ostrich feathers: to his wife, the Princess, he bequeathed a hall of red worsted, embroidered with eagles and griffins, with a border of swans having lady's heads; and to Mons. Aleyne Cheyne a bed of camoca, powdered with blue eagles. In 1385, Joan Princess of Wales bequeathed "To my dear son, the King, my new bed of red velvet, embroidered with ostrich feathers of silver, and heads of leopards of gold, with boughs and leaves issuing out of their mouths." Edward, [Note. Edward assumed to be a mistake for Edward?] Earl of March, in 1380, bequeathed to his son and heir, "our large bed of black satin, embroidered with white lions and gold roses, with escutcheons of the arms of Mortimer and Ulster;" and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, in 1397, bequeathed to the altar of St. Paul's cathedral "his great bed of cloth of gold, the champepiers powdered with golden roses, placed upon pipes of gold, and in each pipe two white ostrich feathers;" and again, to his daughter the Duchess of Exeter, his "white bed of silk, with blue eagles displayed." In 1415, Edward, Duke of York, bequeathed to his wife "my bed of feathers and leopards, with the furniture appertaining to the same; also my white and red tapestry of garters, fetter-locks, and falconsb".

Note b. Nichols's Royal and Noble Wills. Nicolas's Testamenta Vetusta.

Rising Sun

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. I will now proceed to notice in succession the several devices with which the robes of the Effigies before us are adorned. The robes of the King are powdered or strewn with three badges, the White Hart, the Broom Plant, and the Rising Sun. Among them are intermixed the letters R and A, the initials of Richard and Anne. The borders of the robes are ornamented with elegant patterns minutely delineated, the principal being a running scroll of the Broom-plant; at the foot are two rows of ermine spots, and the hood is also lined with ermine, but the inner sides of the mantle are plain. The badges on the mantle are interwoven with running lines of flowers or small leaves, in a manner so nearly resembling a curious painting of Richard the Second which is now preserved in the Earl of Pembroke's collection at Wilton, that, before I proceed further, I shall take some notice of that picture.

Stars

Estoile

Estoile. A six pointed star.

Danvers Arms. Gules a chevron or three estoiles. Source.

Danvers Arms. Gules a chevron or three estoiles. Source.

Hobart Arms. Sable, an estoile of six points or between two flaunches ermine.

Hobart Arms. Sable, an estoile of six points or between two flaunches ermine.

Mordaunt Arms. Argent, a chevron between three estoiles sable. Source.

Mordaunt Arms. Argent, a chevron between three estoiles sable. Source.

Robartes Arms. Azure, three estoiles and a chief wavy or. Source.

Robartes Arms. Azure, three estoiles and a chief wavy or. Source.

St John Arms. Argent, a chief gules two estoiles or. Source.

St John Arms. Argent, a chief gules two estoiles or. Source.

White Hart

Monumental Effigies. King Richard II and his Queen Anne of Bohemia. Remarkable decoration of White Harts, sunbursts, broom cods on his clothes, as well as the initials A and R. Similarly, her clothes are decorated with the Ostriches with a nail in the beak, a symbol of Bohemia, from which the ostrich feathers, and entwined knots. Note his beard as also seen in portraits.

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. I will now proceed to notice in succession the several devices with which the robes of the Effigies before us are adorned. The robes of the King are powdered or strewn with three badges, the White Hart, the Broom Plant, and the Rising Sun. Among them are intermixed the letters R and A, the initials of Richard and Anne. The borders of the robes are ornamented with elegant patterns minutely delineated, the principal being a running scroll of the Broom-plant; at the foot are two rows of ermine spots, and the hood is also lined with ermine, but the inner sides of the mantle are plain. The badges on the mantle are interwoven with running lines of flowers or small leaves, in a manner so nearly resembling a curious painting of Richard the Second which is now preserved in the Earl of Pembroke's collection at Wilton, that, before I proceed further, I shall take some notice of that picture.

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. It is painted on two tablets, and Hollar engraved it in two plates in the year 1639; but the two when viewed together form but one design. The King is kneeling in prayer to the Virgin and her Son; behind him stand the three saints, John the Baptist, Edward the Confessor, and Edmund the King. Behind and around the Virgin are eleven angels. King Richard is here attired in a gown powdered with White Harts, which are interlaced with Broom-cods running in the same manner as the interlacing foliage on the mantle of his Effigy. He wears round his neck a collar of Broom-cods; and on his left shoulder is his badge of the White Hart. But what is more extraordinary is, that each of the eleven angels wears a similar collar and a similar badge. It must be remarked that the pendant to the collar in front, in every case, is formed of two of the Broom-cods only; and that the King, as well as the angels, wears the White Hart, as a badge, on his shoulder, not as a pendant to the collar, as was misapprehended by Anstisg. It was this picture which furnished a subject of discussion to Walpole in connexion with the alleged discovery of oil-painting by Van Eyckh; but it was proved to be painted in water-colours, on an examination by T. Phillips, Esq. R.A. as is noticed in Britton's Beauties of Wiltshire. It formerly belonged to the Royal Collection, but is said to have been given away by King James the Second to Lord Castlemaine, about the time he went Ambassador to Rome, after whose death it was purchased by the Earl of Pembroke, and added to the Collection at Wilton.

Note g. Register of the Order of the Garter, vol. i. p. 112; and also in p. 110. Anstis was here writing of collars, and he did not sufficiently bear in mind that the badge, stigma, mark, sign, or cognizance was another thing. He followed the verses under Hollar's print, in which it is erroneously said, "Pendulus est albus cervus," &c. Anstis, in turn, is followed by Mr. Beltz, who states that the White Hart was "pendent from a collar," in his Notices of Collars of the King's Livery, Retrospective Review, new series, vol. ii. p. 501.

Note h. In reference to this subject, see a paper by the present writer in the Gentleman's Magazine for Nov. 1840, vol. xiv. p. 489, relative to a picture in the Duke of Devonshire's villa at Chiswick, which was assigned by Walpole to Van Eyck, and supposed to represent the family of Lord de Clifford, but regarding which, Mr. Waagen has pronounced that "Jan Van Eyck is quite out of the question," and which is shown (ubi supra) to be the portraits of Sir John Donne and his wife Elizabeth, sister to Lord Hastings, temp. Edw. IV. They wear the collar of that King's livery, formed of alternate roses and suns, with a white lion sejant as a pendant.

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. The writer of the Life of Richard, edited by Hearne, states that the badge of the White Hart was first given at the time of the Tournament held in Smithfield in 1396 for the entertainment of the Count of St. Pol and the Count of Ostrevandt:—

"Ubi datum erat primo signum vel stigma illud egregium cum Cervo Albo, cum corona et cathena aurea." [Where was first given that excellent sign or mark with a white stag, with a golden crown and chain]

Archaeologia Volume 29 Section III. But it is less probable that the White Hart was first givenl on that occasion, than that it was then brought into conspicuous notice by being displayed upon all the housings and accoutrements of the English knights who took part in the tournament, as the accounts given by Walsingham and in the Polychronicon state that it was. Indeed, as Anstis has pointed out (though with a wrong date, as it belongs to Richard's sixthm and not his ninth year), there is a document in Rymer some years earlier in date, which enumerates various crown jewels pawned to the Corporation of London, among which occur three brooches in the form of White Harts, set with rubies. It should, however, be added that in this document the White Hart does not come prominently forward, for there were more brooches of other patterns; as, of twenty-three in the whole, four were worked with a Griffon in the middle, five were in the form of White Dogs, one great one with four Blue Boars, four in the form of Eagles, three in the form of White Harts, and six in the form of Keys. Still there is ample evidence that the White Hart was made very conspicuous on occasion of the Tournament already mentioned, and it is remarkable that a passage has been foundn in the household-book of Richard's great adversary the Earl of Derby (afterwards Henry the Fourth) for that very year, recording the expenditure of 40s. for the embroidering of two sleeves of red velvet and a pair of plates of the same suit, with the Harts

Note l. The devise of "le Cerf volant, couronné d'or au col," had been adopted ten years before, viz. in 1380, by Charles VI. of France, according to his historian, Juvenal des Ursins; who connects it with a legendary story of the collar having been placed upon the Hart in its youth by Julius Cesar; which legend is also related by Upton and by him located in Windsor Forest, at the stone called Besaunteston near Bagshot. (Nic. Upton de Studio Militari, 1654, p. 159.) The same legendary beast was adopted as a supporter by the family of Pompei in Italy in token of their allegiance to the Emperor, with the initials N. M. T. alluding to the inscription on the collar of the original Hart, Nemo Mg Tanear, Casaris svm. (Anstis, Register of the Garter, i. 113, from Menestrier, Ornem. des Armes, p. 118.) Froissart ascribes the origin of the fying hart of Charles VI. to a dream of the king, the story of which occupies his CIVth chapter. It was represented winged, as it appears in the engraved title of the Compendium Roberti Gaguini super Francorum Gestis. Paris, fol. 1504.

Note m. See Rymer's Foedera, edit. 1740, vol. IIT. part iii. p. 140.

Note n. Anstis, i. 14.