Effigy of Henry IV and his Queen Joan of Navarre

Effigy of Henry IV and his Queen Joan of Navarre is in Monumental Effigies of Great Britain.

THESE effigies are both on one altar-tomb in the cathedral at Canterbury [Map]. Henry the Fourth, surnamed of Bolingbroke, from the castle in Lincolnshire [Map] where he was born, about the year 1366, was the son of John of Gaunt by his first wife, Blanche, daughter of Henry Duke of Lancaster. Thus in blood he was truly royal; for Edward the Third was his paternal grandfather, and he descended directly, by his mother's side, from Edmund Crouchback, first Earl of Lancaster, the second son of Henry the Third. His first wife, and the mother of all his issue, was Mary, second daughter and coheiress of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Essex, in whose right he was created Duke of Hereford by King Richard the Second, and bore also, after his father's death, the title of Duke of Lancaster, and Earl of Derby. Having taken occasion one day, in conversation with Thomas Mowbray, first Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal of England, to animadvert somewhat freely on his cousin King Richard's misgovernment, Norfolk denounced him to the King as a traitor. Bolingbroke recriminated on him as a malignant forger of seditious tales, and requested the King to allow him to clear himself by the trial of battle, "by the stroke of a spere and the dent of a sworda." They both in the royal presence interchangeably threw down their gages, and the King appointed a day at Coventry for the adjustment of this quarrel by legal duel. In a work of this character, it may be peculiarly allowable to follow the old chronicles in the description of so chivalrous a ceremony. On the appointed day the Dukes came to Coventry, accompanied by the noblemen and gentlemen of their lineage, who encouraged them to the fight. The Duke of Albemarle, or Aumarle, and the Duke of Surreyb,- the one High Constable and the other High Marshal of England for the day, entered the lists with a numerous body of attendants, each of whom was attired in silke cendal, having a "tipped staff" in his hand to keep the held in order. About the hour of prime (six o'clock in the forenoon) Bolingbroke came to the lists armed at all points, mounted on a white courser, barded with blue and green velvet, embroidered sumptuously with swans and antelopes of goldsmiths' work. The Constable and Marshal demanded of him at the barriers who he was ? "I am," replied the noble appellant, "Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford, who am come hither to do my devoir against Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, as a traitor untrue to God, the King, his Realm, and me!" Then he was immediately sworn upon the Gospels that his quarrel was true and just, and therefore he desired to enter the lists. He then returned his sword to the scabbard, put back his vizor, crossed his forehead, entered within the barriers, alighted from his horse, and sat down in a chair of green velvet, which was placed under a canopy, also of velvet, at one end of the lists. Soon after, King Richard entered the held, in great state, accompanied by the Peers of the Realm, and the Earl of St. Paul, who had journeyed post from France expressly to see this challenge. The King had above ten thousand men in harness with him as a guard. He ascended a stage, royally decorated, and seated himself. A herald forbade, in the Constable's and Marshal's names, ail persons, on pain of death, from touching the lists, except the officers for marshalling the held. Another herald then proclaimed aloud these words: "Behold, Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford, Appellant, is entered the Lists Royal to do his devoir against Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, Defendant, on pain of being proved false and recreant." During this time the Duke of Norfolk, completely armed, was wheeling about before the entrance to the lists on his destrier, barded with crimson velvet embroidered with silver lions (the bearing of his house) intermixed with mulberry-trees. When he had taken the oath that his quarrel was just and true, he rode within the barrier into the held, exclaiming aloud, "God defend the right!" and sat him down in a chair of crimson velvet canopied with white and red damask. The Marshal then measured the spears, to see they were of equal length. He himself delivered one to the Appellant, and sent the other to the Defendant by a knight. At the King's command, the seats of the champions were now removed, they mounted their coursers, closed the beavers of their helms, threw their lances into rest, the trumpets sounded, and the hery steed of Bolingbroke rushed forward to the course. The Duke of Norfolk's horse was not yet at his full pace, when the King cast down his warder. The heralds called "Ho! ho!"— the signal for arresting the combat. The King's Secretary, Sir John Borcy, then read from a roll the decision of the King and Council, publicly declaring that Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford, Appellant, and Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, Defendant, had entered the Royal Lists to "darrain" battle like two valiant knights, but that, because the point in dispute between them was great and weighty, and as Henry Duke of Hereford had displeased the King, he was, within fifteen days, to depart the Realm, not to return for ten years, on pain of death. That Thomas Mowbray, having sown sedition of which he could make no proof, was also to avoid the Realm, never to approach it or its confines again, on pain of deathc. A summary sentence, more intended to adect the revenues of these noblemen than to answer the ends of justice, and of which Bolingbroke gave Richard in a short time ample reason to repent. Bolingbroke retired to France; and Richard, on the death of his father, John of Gaunt, seized his estates into his own hands.

Note a. Hall, reprint, p. 3.

Note b. Edward Plantagenet, son of Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, was created Duke of Albemarle, and Thomas Holland, Earl of Kent, Duke of Surrey, by Richard the Second; both were deprived of these dignities by King Henry the Fourth.

Note c. With what a faithful adherence to Hall's Narrative, and with what spirit has Shakspeare dramatised this scene! Richard thus pronounces sentence on Norfolk in the play.

"Norfolk, for thee remains a heavier doom,

Which I with some unwillingness pronounce.

The fly-slow hours shall not determinate

The hateless limit of thy dear exile;

The hopeless word of Never to return,

Breathe 1 against thee, upon pain of life!"

Richard 11. act i. scene 3.

In 1399 the banished Bolingbroke returned to his native shores, and landed at Ravenspurg on the coast of Yorkshire. Richard was deposed, and he was elevated to the throne in his place, notwithstanding the superior claims of Edmund Mortimer, Earl of Marche. Henry by no means, however, succeeded to an undisturbed sway. While Richard was yet alive and in confinement at Pontefract Castle, a mock Richard was found to personate him by the Earls of Huntingdon, Kent, Salisbury, and Gloucester. This conspiracy defeated, the unfortunate royal captive was privately put to death as a matter of state policy. The rebellion of the Percys which followed in 1403 was put an end to by the victory of Shrewsbury, in which fell the gallant Henry Percy, "the Hotspur of the North." His father, the Earl of Northumberland, in 1408, made a second attempt at revolt, which cost him his life.

Henry enjoyed the crown, that

"polished perturbation! golden care!"

the object of his chief ambition, but fourteen years. While the more tranquil state of his affairs was giving him leisure to prepare for an expedition to the Holy Land, to recover, like the old Crusaders, the place of Christ's passion from the infidels, he was struck with an apoplexy, under which he sunk on the 23d March 1413, in the 46th vear of his age.

A marked characteristic of his ruling passion appeared in his desiring the crown so indirectly obtained, to he placed on a pillow at his bed's head during his last illness. He clung to the splendid bauble with the fondness of a child for a favourite toy. The motto of his device, "Soverayne," seems to have been imagined under the same influence of mind. His body was conveyed to Feversham by water, and thence by land to the cathedral of Canterbury, where it was interred on the Trinity Sunday following his death, with much state, his son Henry the Fifth and many nobles attending. There is an improbable tale on record that they followed but an empty coffin, which the opening of the tomb could only entirely refutea.

Note a. Testimony of Clement Maydestone, that the body of Henry IV. was thrown into the Thames, and not buried at Canterbury. From a Roll in the Library of Corpus Christi College, M. XIV. 98.

"About thirty days after the death of Henry IV. there came a certain man of his household to the House of the Holy Trinity at Hounslow for refreshment. And while they were conversing at dinner about the righteousness of that King's manners, the said man answered to a certain squire Thomas Maydstone, sitting at the same table, that God knew if he were a good man. But this most truly (said he) I do know, that when his body was conveyed from Westminster towards Canterbury in a small boat to be buried, I was one of those three persons who threw it into the sea between Berkingham and Gravesend. And, he added with an oath, that so great a tempest and sea burst upon us, that many noblemen following us in eight vessels, were so scattered that they hardly escaped with life. But we who were with the body, driven to despair of our lives, with common consent, threw it into the sea, and kept the matter very silent. But the chest, in which he lay, covered with a golden pall, we carried with much ceremony to Canterbury and buried it. Therefore the monks of Canterbury say, that the sepulchre (not the body) of Henry IV. is with us. Almighty God is witness and judge, that I saw that man, and that I heard his asseveration to my father Thomas Mavdestone, that all the aforesaid things were true.—CLEMENT MAYDESTON." From the Latin in Peck's Desiderata Curiosa, vol. 1.

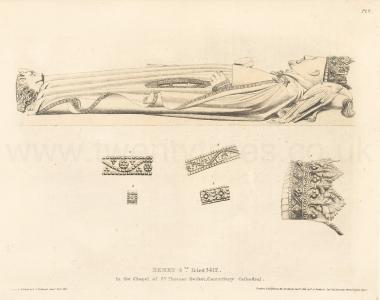

Henry the Fourth was twice married, first to Mary de Bohun, younger daughter and coheiress of Humphrey Earl of Hereford, Essex, and Northampton, High Constable of England, by whom he had issue Henry Prince of Wales, Thomas Duke of Clarence, John Duke of Bedford (Regent of France temp. Henry VI.), Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, Blanche Duchess of Bavaria, and Philippa Queen of Denmark. Mary de Bohun died in 1394, and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. Nine years after he espoused Joan, daughter of Charles the first King of Navarre, and widow of John de Montfort, Duke of Bretagne. She died without children, at that ancient seat of the English Kings from the Saxon times, Havering-at-the-Bower [Map], in Essex, the 10th of July, 1397, and was buried at Canterbury Cathedral, where a sumptuous tomb, with the effigies delineated in this work, commemorates herself and her husband. The tomb is on the north side of the Trinity chapel, in which stood the shrine of Thomas a Becket, and opposite to the monument of Edward the Black Prince. It is of alabaster, painted and parcel gilt, of the richest workmanship, but has suffered much from barbarous mutilation. The figures are crowned, robed, and bore in their hands, no doubt, the other ensigns of royalty, which are now broken away. The Queen has round her neck a collar of SS; an ornament which is often repeated on other parts of the tomb, as is the King's motto "Soveraynewe", may therefore strongly infer that the letters SS are used as the initials of that favourite "impress." The earliest instance of the collar of SS is that, we believe, now before us. The King's word "Soverayne," with an eagle surmounted by a crown, and the Queen's "a temperance," with a small animal, said to be an ermine or a gennet, similarly surmounted, adorn the cornice round the canopy of the tomba, which is further decorated with several armorial coats of contemporary nobles.

Details. Plate I. 1. Band, &c. attaching the mantle of the King to the shoulders. 2. Band, border, cordon, &c. of the Queen's mantle. 3. Her collar of SS. 4. Jewelled studs in the front of her cote hardie.

Plate 2. Profile of the King. 1. The Crown of State enlarged. 2. Jewelled border of the cuff 3. Ditto of the mantle. 4. Ditto of the side apertures of the dalmatic. 5. One of the two clasps closing the above aperture.

Plate 3. Profile of the Queen. 1. Portion of the Crown enlarged, with fret for confining the hair. 2. Border of the mantle.

Note a. The ceiling of the canopy of the tomb is said to have undergone two paintings. The first painting consisted of eagles and greyhounds, surrounded by the garter, having the words, "Soverayne," "A Temperance," between in diagonal stripes; the last, of the eagles and gennets placed as stops between the above inscriptions.