Henry Chaplin A Memoir

Henry Chaplin A Memoir is in Modern Era.

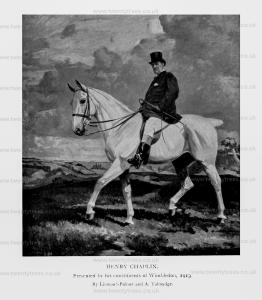

Henry Chaplin. A Memoir. Prepared by his daughter The Marchioness of Londonderry (age 47). 1926.

Books, Modern Era, Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Preface

PREFACE

It had always been my father's wish that some account should be made public of the part he had taken in the spheres of politics and sport. For this purpose certain letters and memoranda are extant— the latter in many cases dictated by himself, and from time to time amplified. A selection of this material has accordingly been prepared.

In presenting this record of the events of a long life, I must, in the first place, acknowledge with dutiful thanks the gracious permission of H.M. the King to publish certain letters written to my father by His late Majesty King Edward VII. and Her late Majesty Queen Alexandra.

Next, I must express my warm sense of obligation to many helpers. I am deeply indebted to my friend, Miss Rose Bradley, for the time and trouble she has so generously bestowed, not only in the co-ordination of the documents bequeathed by my father, but in the preparation of part of the narrative. An old friend of my father and myself, whose desire for anonymity I am bound to respect, is responsible for the section on Racing. My friend, Mr. John Buchan, has given me invaluable assistance in various sections, and has supervised with me the arrangement of the book.

For other services most kindly rendered by Helen Countess of Radnor (age 79), the Duke of Portland (age 68), Lord Lonsdale, Lord Charles Bentinck, Mr. Ernest Chaplin, Lieut.-Col. Charles Brook, Major E. C. Ellice, Sir Theodore Cook, Colonel A. Macauley, Mr. W. Danby, and Mr. Golding, I beg to express my sincere thanks.

I hope that this tribute of a daughter to the memory of her father may meet with some measure of approval from his many friends, and from the still wider circle to which for so many years he was a familiar figure.

E. LONDONDERRY (age 47).

Books, Modern Era, Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Contents

Books, Modern Era, Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Illustrations

ILLUSTRATIONS

The Hamby Monument in the Church of St Vedast, Tathwell

Henry Chaplin, ætat 9. Lady Florence at the time of her marriage.

Lady Florence Chaplin

Dunrobin Castle, Sutherland

Mr. Chaplin and his grandson, Viscount Castlereagh

Mr. Chaplin at Mount Stewart

Political Cartoons—In Swaziland

Political Cartoons—The Unknown Animal

Political Cartoons—The Return of the Dodo

Political Cartoons—That Baby Again

Political Cartoons—The Bird and the Salt

Political Cartoons—Trespassing

Henry Chaplin, 1907

A Meet of the Burton Hounds

Guardian—Entered 1867.

Charles Hawtin and Harry Dawkins

Meet of the Blankney Hounds

The Miller

The Blankney County I

The Blankney County II

Mr. Chaplin and Lord Willoughby de Broke

With the Cottesmore Hounds

Mrs. W. Ellice (in colour)

Caricature of Henry Chaplin by Prosper Merimée (in colour)

The Kyle of Tongue (in colour)

Emperor I.

Captain Machell

The Marquis of Hastings

Hermit, Winner of the Derby, 1867 (in colour)

Books, Modern Era, Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Chapter I Youth 1841-1868

I often think Mr. Chaplin said once, in a reminiscent mood, a few months before he died, "that Providence intended me to be a huntsman rather than a statesman. Horses and hounds have always been a passion with me from my earliest days, and always will remain so as long as I can get on to a horse at all." He spoke advisedly. He knew well that politicians will come and that politicians will certainly go. Sturdy fighter in and out of the House of Commons though he was, and staunch upholder of what he held to be the interests of his country, it is where horses and hounds and men are gathered together, and as long as racing remains the national sport of England, that the name of Henry Chaplin will be best remembered.

But when he died on May 29, 1923, it was universally felt that the world had lost more than an outstanding figure on the turf and in the hunting field—more than a great authority on agriculture— more than a singularly picturesque and lovable personality. The "Squire" as he was affectionately called by his friends, was all these things. But he was something else. In spite of his vigorous individuality, he was a representative—almost the last representative—of that type of landed gentry whose political and social influence had meant so much to Victorian England. He belonged essentially to that old school of country gentlemen to whom a long line of squires had bequeathed a tradition of responsibility to their country no less than to their acres.

Times have changed. Heavy taxation and lengthy periods of agrarian depression have given the squire of to-day, where he still exists, small chance of playing a prominent part in politics, or of maintaining that generous outlay on sport and that lavish hospitality which were a matter of course to his forebears. The great country houses where Victorian society met and Victorian politicians discussed Cabinet secrets, have mostly passed into the hands Of strangers who belong to a different world and have inherited no traditions with the acres they have purchased, or they have lapsed into the unfeatured dullness of state institutions. This memoir of Mr. Chaplin has, therefore, the interest of a completed chapter to which there can be no sequel. It tells of men and women and modes of life that will not come again.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I

The Chaplins had been squires in Lincolnshire since the year 1658, when on the marriage of John Chaplin with Elizabeth Hamby, only daughter and heiress of Sir John Hamby of Tathwell in that county, they removed thence from Wiltshire. John Chaplin's father, Sir Francis Chaplin of the Clothworkers' Company, was Lord Mayor of London, and lies buried in the Church of St. Catherine Cree in the City, close to the grave of Sir William de Bouverie. It is a curious coincidence that at about the same time as the Chaplins left Wiltshire, Sir William de Bouverie's son Edward bought Longford Castle [Map], almost adjoining their former property; and nearly 200 years later, a daughter of the Chaplins (Helen, Countess of Radnor (age 79) — Henry Chaplin's sister) married another Pleydell-Bouverie [William Pleydell-Bouverie 5th Earl Radnor], and thus linked two families which had been long before near neighbours.

John Chaplin settled on his wife's property at Tathwell, and became High Sheriff of the county. The Hambys traced their descent direct from Walter Hamby of Hamby in the county of Lincoln, who lived in the time of King Edward I. They had all been more or less notable figures in their own shire, and more than one had married an heiress from another part of England, thereby adding not only substance to their money bags, but also quarterings to their coats of arms. Elizabeth Hamby's mother was daughter and sole heiress of Richard Porter of Lamberhurst in Kent, and her paternal grandmother, the wife of Francis Hamby, had been Magdalen Leeds, an heiress from Sussex. So Tathwell, which now passed by marriage to the Chaplins, was a very goodly heritage.

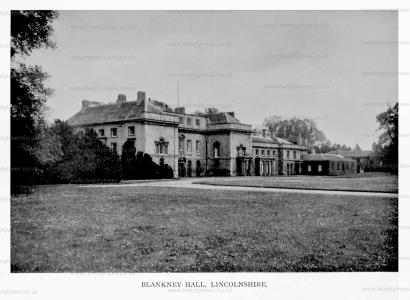

John Chaplin's younger brother Robert represented Great Grimsby in Parliament, and was granted a baronetcy, but, dying without a son, the title passed by special remainder to John's grandson (age 19) and namesake, a son of Porter Chaplin. This young man died of the small-pox in 1730, after a few days' illness; as he left no male heir and only a posthumous daughter, the title became extinct and the property of Tathwell, which was entailed, went to his uncle Thomas (age 46), another son of John Chaplin. It is to Thomas Chaplin that his descendants owed the estate of Blankney, which he bought and made his home in 1719. From that date until the close of the nineteenth century, Blankney was the Chaplin home.

The demesne of Blankney had been the property of the Deincourts since the Conquest, until in the fifteenth century it passed through the marriage of an heiress [Alice Deincourt 6th Baroness Deincourt, Baroness Lovel and Sudeley] to the Lovels of Tichmarsh. All the estates of the house of Lovel were, however, confiscated to the Crown by Henry Vll., after the battle of Stoke-on-Trent, when Lord Lovel himself only escaped by swimming his horse across the river. Blankney was bought by the Thorolds, who did much to embellish the house with the fine carved panelling of the period. But in the reign of Charles I., through a marriage with the Thorold heiress [Mary Thorold], it passed into the hands of Sir William Widdrington, who was created Baron Widdrington of Blankney in 1643. Lord Widdrington's great grandson [William Widdrington 4th Baron Widdrington] had the indiscretion to take part in the rebellion of 1715; he was taken prisoner at Preston and convicted of high treason, and though his life was spared his estates were confiscated in the following year.

A tradition of hidden treasure at Blankney Hall survived for more than a century. When Lord Widdrington was attainted it was said that, foreseeing the confiscation of his land, he endeavoured to secure as much of the movable property as possible by concealing it in secret places, and a legend ran that he had deposited a large chest of plate in a vault beneath the great staircase. The family hopes, however, were dispelled when on one occasion, having workmen in the house, Mr. Charles Chaplin, uncle of the last squire, ordered the vault to be opened. The oak chest was there indeed, but it only contained a salt cellar of white metal and an iron ladle. Either Lord Widdrington had deliberately misled the Government treasure-seekers, or thieves had cheated posterity.

Three years later, in 1719, Blankney, twice the sport of political circumstance, was purchased from the Commissioners of Confiscated Property by Thomas Chaplin (age 35), who in the following year married Diana, sister of Thomas Archer (age 23), afterwards Baron Archer of Umberslade.

In the north chancel of the Church of St. Vedast [Map] at Tathwell the beautiful Hamby monument still remains. Beneath the shield bearing the Hamby arms and quarterings is a Latin inscription to the memory of William Hamby, Esq., who "peacefully fell asleep in the Lord on the 25th day of January, 1626". Below the inscription he kneels in a black robe at a desk with a book. Lower down on the monument are the figures of his brother Edward and his wife Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of Francis Read of Wrangle, "who begat a numerous progeny and were the grandparents of Sir John Hamby. On either side of these effigies, who also kneel at a desk, are three shields of the arms of the Hambys and Reads and their quarterings. A white marble slab of later erection is inscribed to the memory of John Chaplin, Esq., who died in 1714, and his wife Elizabeth, only daughter and heiress of Sir John Hamby.

On the other side of the chancel [at St Vedast's Church, Tathwell [Map]] is a monument to Thomas Chaplin on which the Latin inscription — translated — runs thus:

Sacred to the memory of Thomas Chaplin, Esq., a kind and blameless man, who having enjoyed a happy fortune and living honourably performed all the duties of life deserved to be buried in this place among the remains of his great grandparents whose simplicity he expressed in his character, nor will any fear shame his posterity if they are like him. He was born A.D. 1684 and died A.D. 1747.

This is followed by a tribute in verse which appears to include his wife:

The knot of love which twixt these two was knit

It held full fast till death untyed it.

Whoso in true and honest love do live

To such the Lord especial grace doth give.

Well may we hope they come to blessed end

Whom for their truth and love we may commend.

On one side of the monument are six sons kneeling, two of whom, one a youth and the other a boy, hold skulls in their hands denoting early death. On the opposite side kneel the seven daughters, three of whom bear skulls, while a fourth is baby in swaddling clothes lying in a cradle.

Thomas Chaplin of Blankney:

In 1684 he was born to John Chaplin.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth I. Three years later, in 1719, Blankney, twice the sport of political circumstance, was purchased from the Commissioners of Confiscated Property by Thomas Chaplin, who in the following year married Diana, sister of Thomas Archer, afterwards Baron Archer of Umberslade. In 12 Jul 1720 Thomas Chaplin of Blankney and Diana Archer were married.

In 12 Jul 1720 Thomas Chaplin of Blankney and Diana Archer were married. Before 17 Jan 1747 Thomas Chaplin of Blankney died.

Before 17 Jan 1747 Thomas Chaplin of Blankney died.

Thomas Chaplin, as we have seen, inherited further the Tathwell estate on the death of his nephew Sir John in 1730, and became a person of "high consideration", both political and social, in Lincolnshire — the first of a long line of notable squires who followed him for 150 years in direct succession. He seems to have had some difficulty over the inheritance of Tathwell, for he writes rather testily, referring to Sir John's executors or the lawyers: "The gentlemen have pretty well fleeced the estate that they need not be squeezing for more, and if they had signed the Conveyance sooner, the money would have been ready, and it is not reasonable that anybody should pay for their neglect."

His daughter Diana married in 1749 Lord George Sutton Manners, a son of the Duke of Rutland, while his elder son and heir John formed an alliance with another great house by his marriage with Lady Elizabeth Cecil, daughter of Brownlow, Earl of Exeter. Lady Elizabeth, being for long an only child, was regarded, even until after her marriage, as Lord Exeter's sole heiress, but ultimately a son [Thomas Cecil] was born to him. Had it not been for the birth of this child, the further great inheritance of Burghley would have come to the Chaplins. As it was, Lady Elizabeth brought some very beautiful plate into the family — in compensation, it was said, for the loss of the property. This included a vast silver wine cooler, the size of a bath. The story of its acquisition is as follows: On one occasion when her husband was staying at Burleigh, Lord Exeter after dinner pointed out to his guests a silver wine cooler which he was perfectly prepared to give to any of the gentlemen present, if they could carry it out of the dining-room. Thereupon John Chaplin went down on his hands and knees and, after great difficulty, managed to get the wine cooler on his back and crawled out of the room with it.

It must have been immediately after the marriage of Diana Chaplin (age 18), and probably in honour of that event, that a masquerade was held at Blankney Hall, of which a list of some of the principal guests and their impersonations has been preserved. Thomas Chaplin having died in 1747, his son John (age 28), who was not yet married, was presumably the host on this occasion. He chose for himself the character of Henry V Ill., and if he enjoyed the same splendid proportions as his descendant, the last Squire, his choice was justified. An old yellow torn sheet of paper has been preserved on which in faded ink is written:

A LIST OF THE COMPANY AS THEY DANCED AT THE MASQUERADE AT BLANKNEY, THE 9TH JANUARY 1749.

Lord George Manners (age 25)... A Spaniard

Mr. Glover... A Rich Vandyke

Mr. Chaplin (age 28)... King Harry the 8th

Mr. C. Chaplin (age 18)... A Huzsar

Mr. Amcotts... A Venetian Dancer

Mr. Nevill... Mercury

Sir Francis Dashwood (age 40)... Pluto (King of Hell with a Little infernal boy bearing up his train)

Mr. Pownall... A Vandyke

Mr. Thornton... A Dancer

Capt. Bell... A Chimney Sweeper (in black Satin)

Duke of Kingston (age 38)... In a Gold White Domino

Mr. Carter... A Priest

Major Gibbon... Queen Elizabeth's Porter

Mr. Dashwood (age 32), Bror to Sir Francis... A Russian

Mr. Stevens... A Black Domino

Mr. Porter... Mercury

Mr. Foster... A Domino

Mr. Willis... A Sailor

Mr. King... A Vandyke

Mr. Richd Welby... A Hungarian

Lady Vere Bertie.. A fair Maid of the Inn

Lady Tyrconnel... A Spanish Lady

Miss Wheat... Rubens' Wife

Miss Thornton... Flora

Miss Disney... Violette

Miss N. Amcotts... The Rising Morn

Miss Carter... Queen of the Scots as a widow

Lady Thorold... A Spanish Lady

Miss Mainwaring... Representing Night in a Black Gown with Stars

Miss Maddison... A Country Girl

Lady Dashwood... A Vandyke

Miss Bertie... A Dancer

Miss Bet Hales... An old-fashioned Lady

Mrs. Willie... A Country Girl

Miss I. Cust... Italian Dancer

Miss King... Aurette

Miss N. Welby... A Quaker

Mrs. Porter... A Turkish Lady

Miss Hales... A Country Girl

Miss Lucy Cust... An old Lady

COMPANY THAT SAT BY

Lady Vere Bertie... An Italian Peasant

Lord Tyrconnel... In a blue & silver Domino

Colonel Armiger...

Young Mr. Wills... Capt. Flask

Mr. Middlemore... In a Pink Domino

Mr. Villarial... Scaramouch

Mrs. Chaplin... An Old Woman

Lady George Manners (the Bride) [Diana Chaplin (age 18)]... A Jardiniere

Mrs. Wills... Queen Elizabeth

Miss Truman... Columbine

Among all this motley crowd, not the least imposing figure was probably that of Sir Francis Dashwood (age 40), appropriate in the character chosen, since he was one of the most prominent supporters of the Hell Fire Club.1

Note 1. He was Chancellor of the Exchequer. Wilkes described him as one who from puzzling all his life at tavern bills was called by Lord Bute to administer the finances of the Kingdom which were 100 millions in debt He was the founder of the Society of the Franciscans at Medmenham Abbey, where the door was surmounted by the motto, "Fay ce que voudras" ["Do Whatever You Want"], and where he played the part of an immoral buffoon for the amusement of Privy Councillors and Members of Parliament.

While the adjoining church of St. Oswald's (from which the late Henry Chaplin took his title) was practically rebuilt in the nineteenth century, Blankney Hall was fortunate in escaping the destruction that befell so many castles and houses confiscated at different times owing to the political views of their owners. It has been modernised and altered at intervals according to the taste and the standard of comfort of the period, but to this day it retains all the spacious dignity of an old English country house.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth II

Henry Chaplin (age 1) was born on December 22, 18411, at Ryhall Hall near Stamford, being the third son of the Rev. Henry Chaplin (age 52), the Lord of the Manor and Rector of the Parish, and of Caroline Horatia (age 26), a daughter of William Ellice of Invergarry, M.P. for Great Grimsby, and niece of Horatio Ross.

Note 1. There was some doubt as to the year of his birth. See p. 146.

His father, like all the Chaplins, was a great horseman and follower of hounds, and his children were taught to ride from infancy. He was a country gentleman of the old type as well as a clergyman, and his sons had every opportunity of acquiring that taste for sport and an open-air life which was to be one of their most marked characteristics. Ryhall is close to Burghley, and Lord Exeter, regarding the Chaplins as belonging to his own family, allowed the young people the run of the house and land which had so nearly been their own.

The Rev. Henry Chaplin in 1849 while his children were still young, and though their mother (age 35) took a house in London, in Montagu Square, the greater part of their happy childhood was spent with their uncle Charles Chaplin (age 63) at Blankney. The latter, who represented Lincolnshire in Parliament from 1818—1832, had married Caroline Fane (age 58), a grand-daughter of the 8th Earl of Westmorland. He had no children, and Harry (age 9), the subject of this memoir, after the death of his two brothers, was brought up as his uncle's heir.

Caroline Horatia Ellice:

Around 1815 she was born to William Ellice of Invergarry.

On 19 Aug 1834 Reverend Henry Chaplin and she were married. The difference in their ages was 25 years. On 19 Jun 1858 Caroline Horatia Ellice died.

On 19 Jun 1858 Caroline Horatia Ellice died.

Charles Chaplin was a survivor of a most ancient order of squires. A complete autocrat on his own land, and owning property in three counties, it was said of him that he could himself return no fewer than seven members to Parliament, since to vote the way the Squire ordered was the whole duty of the good tenant. He was regarded with universal respect and a good deal of awe, and was a perfect terror to the poacher. It is told of him that on one occasion when he was sitting on the Bench a young lawyer from London, who was present, ventured to criticise a pronouncement of the Squire's as not legal. "Young man," thundered Mr. Chaplin, as much astounded as he was affronted by the interruption, "you are evidently a stranger in these parts or you would know that my word is law."

Harry as a small boy was sent to Mrs. Walker's school at Brighton, and it was here, while his family were staying in the place, that he suffered his first real grief in the death of his elder and much-loved sister Harriet, who had been his special companion. He was inconsolable at her loss, and his little sister "Mattie (age 79)" (Helen, Countess of Radnor) relates that she earned the one and only snub of her life from "Brother Hal" by her well-meant efforts to heal the wound, with the pious platitudes derived from her nurse.

Mrs. Henry Chaplin — "Mrs. Henry" as she was always called at Blankney to distinguish her from her sister-in-law — was thirty years younger than her husband, and took the place of a daughter to the old Squire and his wife, since she lived so much with them after her husband's death. She was a woman of remarkable ability and of great strength and sweetness of character. She had a wonderful head for figures and was of immense assistance to the Squire, who was Chairman of the Great Northern Railway, which in 1849 only extended to Essendine, a few miles beyond Peterborough. Her daughter can remember her seated constantly before sheets of beautifully neat figures, being the balance sheets of the railway company which she prepared for the use of the Squire, but she was never too busy to attend to the interests, or to listen to the chatter, of the younger members of her family. On their journeys by road from Ryhall to Blankney they travelled in what was known as the "chariot ", and Mrs. Henry, finding the interior of the vehicle stuffy, was in the habit, when the weather was fine, of sitting outside in the rumble. When this was impossible and they had to sit inside, her little girl suffered a good deal from the swaying motion of the "chariot " and she can still remember the entertaining conversation with which her mother throughout the long hours distracted her attention from a physical uneasiness which she herself probably shared.

Blankney was an ideal home for children, and the four boys and their sister do not seem to have found their uncle at all alarming. They were allowed plenty of scope for their high spirits and love of outdoor exercise. They rode the ponies he provided for them — the boys teaching their small sister to ride as well as themselves — Harry, all his life an entirely fearless rider, leading the way over the jumps, but taking care that the little girl should run no unnecessary risk. Very many years later he rewarded his pupil by referring to her as one of the best judges of a horse that he knew; and there could scarcely be a higher compliment from one Chaplin to another.

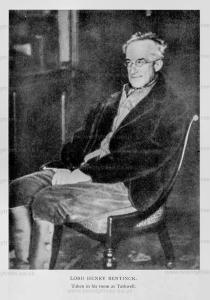

In all matters pertaining to sport, and indeed in most others, the young Chaplins had a perfect counsellor and friend in their neighbour, Lord Henry Bentinck (age 45). He was at the time Master of the Burton Hunt, and Mr. Charles Chaplin was his principal supporter—subscribing £1200 a year. Lord Henry taught the children everything that they had to learn about horses and hounds, and they were proud indeed when he told them that the hounds which had been "walked" by them were among his best. He was a kind of fairy godfather to them all in his own strange way; Harry in especial owed him much, and in spite of the difference in age, there was a close and lasting friendship between them.

Though sport, and above all riding, was naturally the main preoccupation of the children during their holidays, Blankney provided other interests. Their uncle ruled, as we have said, in the autocratic fashion of the squires of his day over his many thousand acres and the picturesque village, but it was a benevolent despotism. The young people were known and welcomed by all the neighbouring tenants, and Harry, the future squire, had very early in life the opportunity of acquiring that intimate and affectionate knowledge of the land and the farmers which was to serve him so well in later life.

Among the old customs which still survived at Blankney was the Blankney Feast, and a record has been kept of one of these held in 1847. The "seven shillings to be run for by first event is donkeys " (best of three heats). We can picture the future M.F.H. and owner of Hermit, at six years old, astride a donkey, urging his mount with youthful zeal and precocious judgment to the winning post; or perhaps coerced by a stern nurse to content himself with backing the favourite—as much as he could see of it over a thoughtless barrier of the voluminous skirts of the period. Other items in the programme include "A cheese to be won by men jumping in sacks", and "A pig with a soaped tail, to be run in all classes by boys under fourteen years of age: to be caught by the tail and dropped over the shoulder. The final item in the programme is "five shillings for a jingling match to last twenty minutes "—for which entertainment the reader may consult the pages of Tom Brown's Schooldays. So serious and sportsman-like were the whole proceedings under the direction of the Squire, that a steward and a clerk of the course were appointed, and no dogs or cats allowed on the course by order of the steward or whom he may appoint ".

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth III

From his dame's school at Brighton, Harry Chaplin went with his brothers to Harrow, but for various reasons he left early and was sent to a private tutor, Mr. Furneaux, at Walton, Northamptonshire, to be coached for Oxford. There is not much record of these years, but it may be gathered from his mother's letters, all of which he carefully preserved, that he enjoyed life to the full and committed all the minor and proper indiscretions of a healthy, high-spirited schoolboy.

Throughout his life he had a profound zest for the simple material pleasures of existence. It was a part of that infectious power of enjoyment which kept him young, and which it was impossible for his companions of the moment not to share with him. But to a wise and affectionate mother, the attendant dangers upon what she felt to be a form of self-indulgence were naturally apparent. Her son's light-hearted expenditure in "tuck shops" called for a serious warning.

"I send you a sad batch of bills to look over," she writes in 1857, and I am sure you will feel sorry when you see how much they amount to, particularly when you remember that almost the whole of this large sum was spent in less than three months... It seems very dreadful to think of throwing away so much money upon eating and drinking when so many are starving! But I won't say any more about it now, my darling boy, as I hope and trust it will be a lesson to you for the future, and that you will ever remember how wrong it is to buy what you have not the money ready to pay for. You cannot think the mischief and miseries it leads to, or the good which must arise from exercising a little self denial.

"I have no doubt they cheat very much at these eating shops, and I do not at all like to pay their bills, but it must be done."

And then, having done her whole duty for the moment in reprimands, Mrs. Henry thankfully turns to congenial matters, gives him some account of the guests staying at Blankney, and begs to be told which day he is returning for his Easter holidays, as Uncle Charles wants to know on account of the mare "

Even as a schoolboy—when he could find time for it—Harry Chaplin was the excellent letter writer which he remained all his life. "I was very glad to get your nice long letter," writes his mother. "Never be afraid of not having enough to tell me. Everything you do interests me." She not only kept up a regular and intimate correspondence herself with her boys, but wisely endeavoured to help them at times with what they regarded as their duty letters to their "I think you ought to write to Uncle elder relations. Willy1 and that he would be much pleased to hear from you. He is so kind that you will not have much difficulty in writing to him. Thank him for his kind letter and tell him you will try to follow his good advice, which I earnestly hope and pray you will, my own dear child. (This was presumably at the time of the boy's confirmation.) And then you can tell him all about Mr. Furneaux and how you like him and your companions and all about Walton."

Note 1. Mrs. Henry Chaplin's brother, William Ellice — one of Mr. Chaplin's guardians.

Mrs. Henry was at this time living wholly at Blankney, her sister-in-law being much of an invalid, and she was constantly engaged in entertaining the Squire's guests. In February 1857 she writes to her son on what was probably his first entrance into society away from home, when he was already, at the age of sixteen, an acknowledged social success.

You gave a charming account of all your gaieties. I think you write very nice letters if you could but improve in the handwriting. I am very glad you enjoyed yourself so much and got on so well. It was very kind of Lady Willoughby asking you to dinner—I liked your going there and to Lady Mordaunt's ball very much. I think the Leamington one was rather an extra, but I suppose it was only for once in a way, and now you must be very steady and studious to show us that you are not the worse for all the gaiety!

And again a month later,

I like your nice letters very much, but I am not sorry you were bored at the Leamington ball, as I am sure you would have been much better at Walton.

Harry, like all her children, was deeply attached to his mother, but at seventeen he was naturally ready to grasp with both hands the pleasures and adventures that life brings to a handsome and popular and, above all, happy-natured young man. With proud and loving anxiety Mrs. Henry strained her eyes to the horizon of that fair sea of fortune on which her eldest son was about to set sail. But she did not live even to see him embark.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth IV

Harry Chaplin matriculated at Christ Church, and went up to Oxford in January 1859. In the previous July he had suffered a severe blow in the death of his mother. Mrs. Henry Chaplin's death was a very real grief to all those who knew her and whose affection she had won by her remarkable character, by her intelligence no less than by her sweetness. To her children the loss was irreparable: to the three young boys at school, to the little girl of twelve, now to be left so much alone with her uncle at Blankney, and certainly not least to her eldest son, just emancipated from the discipline of boyhood and about to start on his university career. Mrs. Henry had shown more than ordinary maternal discernment where her son Harry was concerned. The loss of her intelligent and far-seeing counsel was to mean much to him and his fortunes.

The elder Mrs. Chaplin followed her in November, and the old Squire, doubly bereaved, felt the full burden of responsibility towards the young people left to his care. From his letters to his nephew, which have been preserved, glimpses may be had of the latter's life at Oxford during his first term. On February 5 the Squire writes, on hearing that the young man has suffered the common fate of freshmen of recognised means and position at the hands of the Oxford tradesmen: "You appear to have been sadly plundered on your first arrival at Oxford, but it is, I suppose, no use grumbling. I enclose you an order for £15, but you must recollect this makes up more than the first quarter's allowance. Therefore you must be very careful. I am sorry to hear you have so little to do. If you apply to the Dean I have no doubt he will order you to attend some more lectures." This ingenuous advice was apparently ignored, but the old Squire writes again a month later:

I began to think it was a long time since I heard from you when your letter arrived. I have been at Tathwell the last three days and had other letters to write before I went that I could not answer yours sooner. I was in hopes you would have told me the names of the set you generally live in at Christ Church, as I suppose by this time you are able to give some information as to those with whom you chiefly associate, as it is of the greatest importance not only to your present comfort, but also to your future prospects after leaving Oxford, to have formed a good acquaintance there, particularly as you left Harrow so young.

Caroline Fane:

On 28 Dec 1791 she was born to Henry Fane of Fulbeck and Anne Buckley Batson. Before 1858 Charles Chaplin and she were married.

On 22 Nov 1858 Caroline Fane died.

Before 1858 Charles Chaplin and she were married.

On 22 Nov 1858 Caroline Fane died.

I was at Brickenden about a fortnight since, and I arranged with your Uncle Russell that when you had ascertained what quantity and sorts of wine it was desirable to order, you should write to him and request him to order it for you, and the bill to be sent to me. I will pay it and shall charge it as a part of your allowance. I should not recommend you to order a large quantity, as it is very probable if you do that some of it will be stolen. I hear Lord H. B. [Henry Bentinck] has had some good sport and found plenty of foxes, particularly on this side, but the country is now getting very raw and dry. I am going to London to-morrow to attend a Railway Board. Mattie is Very well.

There is something pathetic in the efforts of this old and childless gentleman to attend to the interests of each member of his adopted family, and to keep pace with the doings of a young man at the University, which, no doubt, he found strangely altered in the fifty years which had elapsed since his own under-graduate days. It is evident that, in common with all parents in all ages, he discovered Oxford to have become an amazingly extravagant place for the next generation.

In March he writes again:

I congratulate you upon being elected into the Christ Church Club. At the time I Was at Oxford, there were no clubs for undergraduates that I ever heard of. It does not appear that many Of your intimate friends are members of the Club. I Can hardly think your vacation will be as early as you suppose, but I shall be glad to see you whenever it occurs. I have ordered the mare to be ready for you. Teddy1 writes that his vacation will not begin till the Wednesday before Easter; Harrow is to be on the 12th or 13th.

Note 1. Edward Chaplin, born 1842, second surviving son of the Rev. Henry Chaplin; Lieut.-Col. in the Coldstream Guards; represented the City of Lincoln in Parliament 1874—80; died 1883.

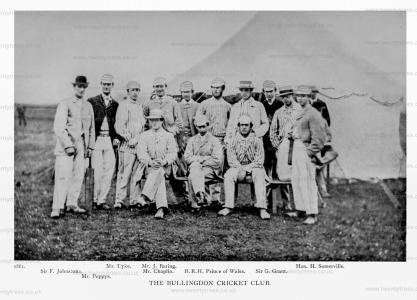

Meantime, as an undergraduate, Harry Chaplin was enjoying himself extremely. As long as King Edward VII. lived, he remained one of his intimate friends, and the Prince of Wales's set to which he belonged in his Oxford days was naturally composed of young men of birth and fortune whose interests at that age were concerned rather more with the pleasures of existence, and especially with sport, than with the academic side of university life. A photograph has been preserved of the Bullingdon Club in 1859, of which he was a prominent member. Among the others were Sir Frederick Johnstone, Bart., who, later, was member for Weymouth, and until his death in 1913 was one of Mr. Chaplin's closest friends; Sir William Hart Dyke, Sir George Grant, Tom Baring, and George Lane Fox.1

Note 1. Eldest son of George Lane Fox, for many years Master of the Bramham Moor hounds.

These young men hunted and raced and entertained their friends and one another, and were entertained at Blenheim and Nuneham and other great houses in the neighbourhood. Some of them in preparation for their future careers talked politics at the Union, but for the majority attendance in the lecture room occupied an inconsiderable portion of their time.

To acquire a knowledge of the kind of life which suited him, and to make congenial friends, seems to have been Harry Chaplin's main preoccupation at this period. Life smiled upon a young man who smiled back as pleasantly as he did, and the death of the old Squire, in May 1859, left him, in his second term at Christ Church, master to a greater extent of his own actions.

To his grandson, Lord Castlereagh (age 23), he once gave an account of his college days. From this we learn that he had four hunters of his own at Oxford, an unheard of number in those days, and, in addition, he had the "command " (the word he used) of eighteen horses belonging to a cousin, a banker, which were stabled at Bicester, the cousin being unable to hunt before January. With a stud of this size he hunted six days a week, and it was very rare indeed for him to spend a whole day in Oxford.

But if life smiled upon the young man, the authorities were inclined to be less lenient. It had not infrequently occurred that Harry Chaplin had been summoned to the handsome and commanding presence of Dean Liddell and lectured for some such venial offence as the wearing of hunting kit under his surplice in Cathedral. One morning, however, the matter proved to be more serious. The familiar blue slip reached him at breakfast and he made haste to obey its summons. But on this occasion the Dean greeted him with all that impressive severity before which more than one generation of delinquents was destined to tremble.

"My dear Mr. Chaplin," he began austerely, "as far as I can gather you seem to regard Christ Church as a hunting box. You are hardly ever in college, and I must request you, unless you change your habits, to vacate your rooms and make way for some one who will benefit from his studies during his residence at the University." The reply was remarkable even to one so familiar with the vagaries of youth as Dean Liddell. "But, Mr. Dean, what do you expect me to do?" "Do," replied the Dean, "you must go in for an examination." "My dear Mr. Dean" — and the undergraduate's answer this time in spite of its suavity, was not unmixed with mild reproof — "if only you had told me before, I should have taken the necessary steps; but when is there one?" "In three weeks," was the curt reply.

The ingenuousness of Harry Chaplin's attitude may be partially explained by the fact that he was what was known in those days as a gentleman commoner, living out of college. In the 'sixties it was not the custom at Christ Church, as it is to-day, to allot every freshman immediately he comes up to a tutor, who will arrange his scheme of work with him for the first year, and instruct him as to what examinations he is expected to take. Harry Chaplin, entirely occupied with matters which seemed to him of greater moment, was genuinely ignorant and had taken no pains to inform himself of what was academically expected of him. But throughout his life it was his habit to do with all his might whatever his hand found to do, provided it were a sufficiently reasonable or pleasurable occupation. So, on this occasion, being impressed by the Dean's arguments, he lost no time in securing the services of a coach whom he described as "an old bottle-nosed man", but with whom, his abilities diverted into this fresh channel being no less effective than his energy, he worked so well that he passed Mods. with distinction.

It was not long before another blue slip reached him at his breakfast table. This time the Dean addressed him with an entirely cordial, if dignified, approbation. "Mr. Chaplin, I must congratulate you on your excellent performance. But now I must earnestly entreat you to go in for the Honours Schools. You have shown us your abilities, and you will become a credit, not only to this house, but to the University if, as I confidently expect, you are successful."

But the Dean was once more to meet with the unexpected from this apparently amenable under-graduate. The taking of a degree had been no part of Harry Chaplin's programme at the University. "When I left Oxford ", he used to say in later life, "I went for my education in big game shooting to and it is probable that his mind had been America fixed for some time upon this other and, as he then considered, more important branch of education. He felt that by his recent success he had done all that could reasonably be expected of him in his college career. "Mr. Dean," he replied politely, "if only you had told me before, I would have done so, but after my last interview with you, in which you intimated that I should have to vacate my rooms, I am very sorry to inform you that I have arranged to go for a trip to the Rocky Mountains."

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth V

Here, indeed, was authority set at nought, but in so suave and so definite a fashion as to be unanswerable. History does not relate whether the Dean attempted a remonstrance, but, as his surviving guardians raised no objection, Harry Chaplin went down from Oxford in 1860. It was owing to the influence of his great uncle, the Right Hon. Edward Ellice, that the projected big game shooting expedition was made feasible. Mr. Ellice, who had been member for Coventry1 and one of the Secretaries of the Treasury in Lord Grey's Administration, became Secretary at War in 1833 and held that office in Lord Melbourne's Government of 1834. He was familiarly known as "Bear" Ellice—for his "wiliness", says Carlyle, but in reality for his close connection with the fur trade. His grandfather had been a merchant in New York, and his father, Alexander Ellice, taking the English side in the War of Independence, moved to Montreal and became managing director of the Hudson Bay Company, for which he supplied much of the capital.

Edward Ellice went out to Canada in 1803 to engage in the fur trade, and it was at his suggestion that in 1820 the competing Canadian fur companies were amalgamated; the Hudson Bay Company, of which he was made Deputy Governor, being given the right of exclusive trade for twenty years. Mr. Ellice had inherited large landed estates both in Canada and in New York State, and in early life he was busily engaged in colonising them. By his marriage2 he became closely connected with the Whig Party, and as an English statesman he played a distinguished part. He refused a peerage, though the sacrifices he had made to politics were very considerable. At Glenquoich, his place in Inverness-shire, his hospitality was the delight of his friends and his young relatives.

Note 1. Mr. Ellice, as a Liberal, was on nine occasions elected member for the borough, his return being contested except at the election of July 1852.

Note 2. The Right Hon. Edward Ellice married Lady Hannah Grey, daughter of Charles, first Earl Grey — widow of Captain Bettesworth.

In 1861 Mr. Ellice's active and helpful interest — at the age of eighty — in his great nephew's projected expedition was naturally of inestimable value. Harry Chaplin's chosen friend, Sir Frederick Johnstone (age 19), was to accompany him, but as this young man was under age and a ward in Chancery, it was not permissible for him to go to so great a distance without an elder and more responsible person. Mr. Ellice was fortunate in procuring for the purpose the services of his friend Dr. Rae, later Sir John Rae, the Arctic explorer and famous scientist, who in the course of his geographical survey of the northern coasts of America had discovered the remains of the Franklin expedition in 1854. Later Dr. Rae had been appointed surgeon to the Hudson Bay Company, and in 1858 Mr. Ellice had made a tour with him through the United States. To shoot buffalo on the plains and ultimately to reach the Rocky Mountains in pursuit of grizzly bear was the intention of Harry Chaplin and his companion, and with this inspiring programme before them they shook the dust of Oxford from their feet, made their preparations and left England in the spring of 1861.

But in New York they found interest of yet another kind awaiting them. Civil war between the Northern and Southern States was declared four or five days after they landed. The forced surrender of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, to the Confederates on April 11, had acted as a live coal to inflame the patriotic passion of the people in the Northern States. This insult to the American Flag could only be wiped out by war, and on the 15th April Lincoln issued his proclamation.

The two young men were naturally in no mind to desert immediately a scene which promised so much dramatic interest. The introductions which they had brought from Mr. Ellice, apparently enabled them to see something of the outbreak of hostilities at close quarters. Harry Chaplin has unfortunately left no written record of his experience, but it is clear that he succeeded in making friends with General Grant, and that the latter made him a present of a pony which he subsequently brought back to England. It appears that he also witnessed from a distance the loss of the great national armoury at Harper's Ferry, which was part of the Confederate design to capture Washington.

The sympathies of the upper classes in England at this time were mainly with the South. Abraham Lincoln's policy was as yet an unknown quantity on this side of the Atlantic. Mr. Edward Ellice, who had visited the United States repeatedly and had a close acquaintance with the politics, had seen the inevitability of the Civil War and its enormous cost. In a letter to Harry Chaplin, which reached the latter in Canada, he expressed in uncompromising language what was probably the opinion of the majority of Englishmen on the outbreak of the war, who had any first-hand knowledge of America.

I have half a century's experience of the people in the Northern States, and have always considered them the most calm and about the most cold, calculating and sagacious sect of the whole race. By what miracle they have been driven mad it is impossible to fathom, but their conduct, in the opinion of every man of intelligence in this country, seems only suitable to the inmates of a lunatic asylum. We look upon the whole scene as Bedlam turned loose and in vain for any keeper to restore order or act physician in the character of statesman to restore them to some reason.

I sympathise sincerely with them in their complaints of their Southern countrymen, but what then? The question is, which was the least of the evils in their manner of dealing with the situation as the last Government left it? They have clearly chosen the worst one of civil war. If they had temporised, done whatever was calculated to secure the Border States, even to the extent of admitting secession of the others—and there are many classes of the Southern people quarrelling with one another—these states would at least have come back in gratitude for escape from dangers through which they found it too difficult to guide themselves. Instead of this they have been rushed blindly into civil war, which, be it successful or not in its military incidents, must defeat all hope of reunion. If they succeed, they can never maintain their dominion as we did in Ireland by a standing army, or reconcile their brothers, so many of them slain in the contest, to associate again in a common government. If they fail, what calamities may not ensue from failure?...

Mr. Ellice died in 1863 before he had time to realise that, thanks to the wisdom and forbearance of Lincoln, the worst of his prognostications were not to be fulfilled.

Meantime, even these most stirring events could not long detain the two young Englishmen from their real purpose. So, no doubt reluctantly, they turned their backs upon fighting which did not after all concern them, and in company with Dr. Rae, set their faces northward to Toronto. From Toronto they travelled in four days to St. Paul, and thence after nine days more they reached the Red River, the navigation of which was in itself something of an adventure.

Mr. Chaplin used to describe in later life how they arrived at Fort Garry, afterwards Winnipeg, in a canoe made out of the hollowed log of a large tree. They found only one stone house and six enormous wooden houses surrounded by a palisade. These were the headquarters of the Hudson Bay Company, where the Red River hunters disposed of the furs which they had collected from all parts of the regions to the north and west. The hunters and trappers remained at the settlement all the winter, and in the spring, when the snow had gone, they were ready for new expeditions. They killed buffalo, of which in those days there were vast quantities on the prairies in the winter, when the coats were long and silky, and they also did a large trade in dried meat from buffalo flesh cured in the sun and in pemmican.

Even at this age and with his mind and body fully occupied with new and engrossing experiences, Harry Chaplin seems to have shown himself the good correspondent which his mother had found him as a schoolboy. "Everybody is delighted with your letters," writes Mr. Edward Ellice from Glenquoich, where he was as usual entertaining a large house party, and from the spirit and health in which you set out on your western adventure, I augur well of the result of your travels. Dimidium facti, qui bene coepit, habet [He who began well is half done]. All things, even your muddy voyage down the Red River, seem to have prospered with you."

Harry Chaplin and his party remained a month or more at Fort Garry, while Dr. Rae collected a small army of men and horses in readiness for the journey to the mountains. These were placed under the leadership of a famous guide, James Mackey, a Scotch half-breed, a man whose character and individuality made a lasting impression upon the young Englishman. Dr. Rae's interest in the expedition was naturally scientific, but in the account which he gave of it in the following year before the Geographical Society, he remarked that "the two young gentlemen whom he accompanied were anxious to kill any and all kinds of game. They travelled over several hundred miles before they could kill an animal larger than a badger. They had the ablest hunters in the country, all picked men, the Red River half-breeds, and their object was entirely to kill game — yet that was the result of their hunting. They would have starved had they not carried plenty of provisions with them."

Dr. Rae reported that the party travelled very hard, having excellent horses—two to each man. After sixteen or eighteen days they came within 150 miles or eight days' journey of the Rockies. Beyond this, it was destined that they should go no farther. The very formidable obstruction in their path was nothing less than the appearance of the Black Foot Indians, a wild tribe living far from civilisation, and now, as it happened, on the war-path.

The Red River hunters and the buffalo runners entirely refused to go through their country. The situation was apparently complicated by the presence in their party of a negro who was acting as cook. The hunters declared that if they approached near enough for the Indians to catch sight of this man, they would insist at whatever cost upon having his scalp, and would pursue them relentlessly until they got him. Nothing would induce them to go a yard farther; even the threats and persuasions of James Mackey were unavailing. So there was nothing for it but to abandon their main aspirations—the Rocky Mountains and the grizzlies. The twelve horses were put back into the twelve carts which accompanied them and the whole party returned in the direction from which they had come.

From a scientific point of view the expedition seems to have been more satisfactory. Dr. Rae was able to establish the latitude of several points on the route and to rectify the position of other places. He also reported to the Geographical Society the discovery by his party of the existence of two salt lakes of considerable size situated among the elevations of the Cöteau du Prairie in the neighbourhood of Moose-jaw which had not previously been placed on the map. He named these the Lakes Chaplin and Johnstone in honour of his young companions. History does not relate how far the latter found consolation in their scientific privileges for the sport to which they had so ardently looked forward. To one at least of them, however, in later years, it was a constant source of entertainment that the lake named after him should originally in the Indian language have been called "The Witches' or Old Squaws' Lake" and that, in the first new map published after the receipt of Dr. Rae's information, it appeared as "Chaplin, or the Old Wives' Lake". Thus it may be found in the Times Atlas at the present day.

Henry Chaplin A Memoir: Youth VI

After his mother's death the paramount influence on Harry Chaplin's life was that of Lord Henry Bentinck. In spite of the disparity of age, Lord Henry had been a good friend to him and to all the family from boyhood. As the young squire grew up the friendship became closer, and Lord Henry was also his guide and mentor on all matters pertaining to sport.1 He was still master of the Burton Hunt when Henry Chaplin came of age, and the latter continued his uncle's subscription of £1200 a year. When in 1864 he wished to be relieved of the mastership Mr. Chaplin bought the hounds from him for £3500.

Note 1. See pp. 198-208 and 260-69.

For some years during the hunting season Mr. Chaplin lived in Lincoln at the old house at Burghersh Chantry. Blankney was on the outskirts of the country, some of the meets being thirty miles distant, while Lincoln was much more central. In consequence he saw a great deal of Lord Henry, who lived what he called his " vagabond life " at an inn in Lincoln, the White Hart, where he had a bedroom and a sitting-room. He had also a first-rate cook and an admirable cellar of his own. Some of Mr. Chaplin's reminiscences of this remarkable man, which in part will be familiar to the readers of Lord Beaconsfield's Life, may be set down in his own words.

Lord Henry and myself were constantly together. I used to dine with him at his hotel and sometimes he used to dine with me and I saw a great deal of him. Everything I know of sport of all kinds he taught me, except racing, and a good deal of politics too. On one occasion when I was dining alone with him after a day's hunting, he told me that in days long gone by it was he and his brother, Lord George Bentinck, who had been the means of enabling Disraeli to become the proprietor of Hughenden, where he lived for the rest of his life.

The way in which Hughenden was acquired was described to me by Lord Henry as follows: Lord George, who was bitterly opposed to the policy of Sir Robert Peel and his particular proposals for the repeal of the Corn Laws, was at that time working hard in Parliament with the aid and assistance of Disraeli, and came down to Welbeck after a hard session, apparently out of spirits and rather downcast and worried, which was most unusual for one of his indomitable courage and ardent spirit. His brother naturally asked him, " What's the matter, George? You don't seem like yourself. Have you got any trouble that is depressing you? "Yes," he said, "I have a great trouble, and it is this. I have found the Party the most wonderful man the world has ever seen, and I cannot get these fools to take him as leader because he is not a country gentleman."

At this Lord Henry burst out laughing, which Lord George was inclined at first to resent. Then he asked him this question, "Is that your only trouble, George? If so, the remedy is perfectly simple. Make him one, George; make him one...." Lord George understood at once what he meant. "If you are ready to help me," he said, "you are right. The matter is perfectly simple."

Now none of the three Bentinck brothers was married, and none of them was likely to marry, and the Duke, their father, was probably the richest man in England at that time. So the three combined had the command of any amount of money that they wanted. Lord George gave instructions forthwith to one of the principal land agents in London, to find at the earliest moment that he could a country residence within easy reach of London, which would be suitable for a prominent politician, or even for a man who might soon be in the position of Prime Minister. This arrangement was quickly carried out by the agent, who secured the offer of the property at Hughenden, which happened at that time to be in the market. This information was conveyed by Lord George, I believe, to Disraeli, and upon such terms by way of mortgage and the interest to be paid thereon as would enable Disraeli with all propriety to take advantage of it.

All this was told me by Lord Henry Bentinck himself on one occasion when I was dining with him alone at Lincoln.1 But what he did not tell me was this; and I did not learn it till Mr. Buckle published the Life of Lord Beaconsfield. What I learnt was that after Lord George's death, it was Lord Henry Bentinck who greatly helped Mr. Disraeli to the leadership of the Party, by the work and energy which he displayed in securing for him the support of many of the most prominent and powerful leaders of the Party. This is amply recognised by Disraeli in the pages of the third volume of Mr. Buckle's fascinating work.

Note 1. The story is to be found in the Life of Disraeli by Monypenny and Buckle, iii. pp. 147-152. Mr. Chaplin was misinformed on one point; there was no intervention on the part of a house-agent. The Disraeli family knew Hughenden well, as it was within easy reach of Bradenharn. Disraeli's father, in the last year of his life, busied himself to secure for him that permanent home in the country, on which both father and son had set their hearts" (loc. cit., page 148).

Lord Henry Bentinck's was in some respects a strange and hard character, though a strong one and capable of the utmost generosity. He was always said to be the favourite son of his father, the then Duke of Portland (age 68), and it was some time after the death of Lord George Bentinck that an unfortunate quarrel arose between Lord Henry on the one side, and his eldest brother, Lord Titchfield (age 32), on the other, and they ceased to be on speaking terms. What it was about I never knew, but it was a question in connection with some property which had been left to Lord Henry in Scotland, I believe, in regard to which he was convinced that Lord Titchfield had behaved badly. Later the Duke became seriously ill, and he died without ever seeing Lord Henry again.

Lord Henry at that time represented in the House of Commons one of the Nottinghamshire seats1 which, as happened in those days, were more or less under the control of the Duke of Portland. Mr. Denison, afterwards Lord Ossington, who had married one of the Duke's daughters, Lady Charlotte Bentinck, and became Speaker of the House of Commons, represented another, and when the next election came, for reasons best known to himself, Mr. Denison thought himself justified in denouncing Lord Henry on the hustings. This created a tremendous sensation in Nottinghamshire. Lord Henry left the county, vowing he would never set foot in it again; and he never did.

Note 1. Lord Henry was Member for North Notts, 1846—57.

Meantime, Mr. Denison, who had made this attack upon Lord Henry, was elected Speaker when Parliament met. In his position as Leader of the Tory Party, it fell to Mr. Disraeli to follow the then Prime Minister in congratulating the Speaker-elect upon the position which he had achieved, and this he did in language which perhaps may have been somewhat exaggerated. Lord Henry told me that after all he and his brothers had done for Mr. Disraeli he did not like it, but after thinking it over he determined to say nothing about it. He afterwards received a long letter from Mr. Disraeli, explaining why he thought it necessary to say what he had done in his speech about the Speaker. Lord Henry's expression to me was that "his letter damned him, and I never will speak to him again".

But now comes a still more remarkable part of the story. The elder brother, who had now become the Duke, had always been a Peelite and so out of sympathy with Mr. Disraeli's politics. Lord Henry, in order to avoid any possible danger of Lord George Bentinck's intentions being interfered with by Mr. Disraeli being disturbed in his possession of Hughenden, said to me, "I posted up to London the moment I became aware of it, went to the Jews and borrowed enough money to pay off sufficient of the debt to prevent the possibility of Mr. Disraeli being ever disturbed in his possession I always remember the expression "posted ", though of it." I do not know whether it meant he merely hurried up, or that the loop line to Lincoln via Boston was not then made.1

Note 1. The following unpublished letters which passed between Disraeli and the fifth Duke of Portland show the relations of the two men:

Confidential.

June 22, 1857.

I cannot resist the conviction that it wd. be more than ungracious on my part, were I to permit the confidential relations wh. have so strangely subsisted between us to terminate in silence.

I am aware of the personal interposition wh. your Grace made on my behalf at the time of the catastrophe. It must have cost you great pain and solicitude, and it merited, & obtained, my gratitude. I am not insensible to the forbearance who I have experienced from Your Grace during the last two years.

A course of kind & considerate conduct wh. has ranged over so long a period, whatever the motive, ought not to be disregarded by the recipient, & I wish to offer my thanks in terms, not conventional, but cordial. Having relieved myself so far, I would hope that Yr. Grace may not be offended, if I express myself with equal frankness on another point. It has been impossible for me, from observations that have occasionally dropped since the death of the late Duke, to resist the inference that Yr. Grace was of opinion that I had taken advantage adroitly of circumstances, & dexterously installed myself in a profitable position.

The time has come when I can touch upon this matter witht. embarrassment.

And in the first place I neither suggested nor sanctioned the original scheme, & if it be thought that I yielded with too great facility, it may be remembered that I was acting under the influence of a person whose position and whose character were alike commanding.

With respect to the subsequent results, the accounts of the estate have been regularly kept, and it appears by the balance wh. has been recently struck, that the pecuniary loss of the project to myself has been little short of ten thousand pounds.

I feel assured that Yr. Grace will bear these unreserved remarks with a manly spirit. There is nothing so painful as to be misjudged by those from whom, whatever may have been the cause, you have received favours, & whom you respect.

I have the honour to remain, Your Grace's obliged & faithful servt.,

B. DISRAELI.

HIS GRACE, THE DUKE OF PORTLAND.

HARCT. HOUSE,

June 23, '57.

SIR—I hasten to acknowledge the receipt this afternoon of your letter of yesterday's date, & to express my very great regret that you should have felt it in the slightest degree called for or expected. I can assure you nothing has ever fallen from me to justify the impression you refer to from "occasional observations".

It was very unfortunate that I should have had to take any part whatever in what has passed, but unavoidable, and I could but endeavour to reconcile as well as might be contending duties.

The whole subject has been a most embarrassing one, & I felt from the first it was impossible I could ever enter in it in detail personally with yourself, and you will forgive me for continuing to abstain from doing so. I much regret the pecuniary loss you mention having sustained, but trust it has been more than counterbalanced in your mind by the high position you have attained.

I have the honour to be, your very obedient servant,

SCOTT-PORTLAND.

THE RT. HONBLE. B. D'ISRAELI.

Whether Mr. Disraeli ever knew this or not I do not know. I do not think he did, and I believe there was only one other man besides myself that ever did, unless it was the late Lord Rothschild or his father Baron Lionel, who was greatly in Mr. Disraeli's confidence. But if he did not know it, it shows what a judge of human character he was, from something he said to me after Lord Henry's death.

When Disraeli was leader of the Party, he used to give on the night before the meeting of Parliament a Party Dinner, at which the Queen's speech was read, and unlike what has been the practice in more recent years, instead of confining his invitations to members of the existing Government alone, he used to ask members whom he considered, I suppose, to be more or less prominent in the Party. Amongst these he was kind enough to include me.1

Note 1. Mr. Chaplin is not quite exact. He has confused two functions. When in office the Leader of the Party in the House of Commons gives a ceremonial dinner to his Front Bench colleagues of the Government, and also invites the Speaker and the Mover and Seconder of the Address. At this dinner the Leader reads the gracious speech from the Throne. The Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons also gives a dinner on the same evening at which he reads The Speech, of which, by courtesy, he receives a copy from Downing Street. To the Opposition dinner the Leader invites the members of his Front Bench, and sometimes also other members of his political connection who may not have held office. In 1871 the Conservatives were in Opposition and Mr. Disraeli gave his dinner, as Leader of his Party in the House of Commons, and there was nothing unusual in Mr. Chaplin being honoured with an invitation. This dinner must have been on February 8, as the Parliamentary Session opened on February 9.

Lord Henry Bentinck had died, I think, on the last day of 18701, and the Party Dinner was given quite early in the following year, 1871. As I was shown into the room, Mr. Disraeli said to me, "Both you and I have lost a great friend since we last parted." I replied, "Yes, Sir, I know that poor Lord Henry and you were great friends at one time, and he has often talked to me about you in those days." "Ah!" said Disraeli, "that is true, and I always wished it could have remained so." And then, after pausing a moment, he went on to say this, "I always said of Henry Bentinck that, taking him all round, I think he was probably the ablest man I ever knew, and with some eccentricities of character he combined the highest qualities of human nature in a greater degree than any I ever was acquainted with." This was a tribute, coming from a man such as Mr. Disraeli, which was indeed striking. It was as just in my opinion as it was striking, in view of the sacrifice which Lord Henry had made from regard for his brother's memory and aspirations, for a man with whom he was at that time not even on speaking terms.

Note 1. This is correct.

A curious instance of the more eccentric side of Lord Henry's character occurred on one occasion when King Edward as Prince of Wales came down to stay at Burghersh Chantry for a week's hunting. Lord Henry did not approve of the Prince of Wales coming to hunt. He had apparently a morbid horror of being supposed to toady anybody. He had, however, a reputation for being the finest whist player in Europe and the Prince was particularly anxious that he should come and dine at the Chantry and have a rubber with him. This, to my extreme annoyance, Lord Henry refused to do.

The Prince came up to me, soon after we got to the Meet, which I had arranged for him at Wellingore Gorse, and said, "I wish you would introduce Lord Henry Bentinck to me." I said, "Certainly, sir," and I brought him up and introduced him. The Prince began in his charming manner — "I understand, Lord Henry, you hunted the county for a great many years and with great success." "Yes, sir," said Lord Henry, "I was king of the county once, but they deposed me as happens to other crowned heads at times." That was the sort of man he was. He did not want to toady him. He told me what had happened, and said, "I don't think he will trouble me much more to-day." I was horrified.

But whatever Lord Henry's eccentricities of conduct, all of us who knew him intimately, my brothers and sister and his few Lincolnshire friends, regarded him with admiration and real affection and always spoke of him as "dear old H.B."

He [Henry William Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck (age 66)] died in a house at Tathwell which he had built for himself, where I had lent him the shooting—10,000 acres with lots of game at that time—and he was buried in the churchyard at Tathwell [Map], where he still lies, though his brother, who had some correspondence with "Little" George Bentinck on the subject, intended at one time to have him interred later at Welbeck.

When I heard by telegram from my brothers, who did not realise what the position was, for I believe he was dead already, that he had been taken suddenly and very seriously ill, I ordered a special train and got Prescott Hewett, a great doctor and surgeon of that time, to go down with me at once to see him.

They had had a hard day's work out shooting in the Wolds with the snow almost up to their knees. Lord Henry had had nothing but tea and toast for breakfast, and refused to have any lunch, taking only a small glass of the brandy for which he was famous.

Walking home that night with Canon Pretyman, the father of the present owner of Orwell, as they parted at the turn for Lord Henry's house, the latter asked him if there was a good doctor in Louth. Pretyman replied that there was a very good man and begged to be allowed to send him out at once, but this Lord Henry declined, saying he would send for him if he required him. On getting home he had a hot bath and went to bed, desiring his servant to say that he wasn't well and would not come to dinner himself, but that his guests were to order for themselves what wine they liked best. Then he went to bed and died, I believe, in his sleep from heart failure very shortly afterwards.

None of them, not even his servant, seemed to be aware that he was ill, and when Prescott Hewett saw the body after we arrived, he expressed the opinion that if he had had a basin of soup, a glass of wine or some brandy and water when he came home instead of the hot bath, he would probably have been as well as ever he had been in his life.

For myself, I can only say this of him—of a man of another generation altogether than mine—he was my oldest, and greatest friend, and I felt for him great admiration, deep affection and profound respect. He taught me all I know of sport, of horses, hunting, hounds and deer-stalking, and a good deal of politics also.1

Note 1. An old man who was a lad in the hunting stables at Lincoln at the time of Lord Henry's death, relates how two teams were taken down from London to Blankney and driven over to Lincoln by Henry Chaplin and Mr. George Lane Fox on both the days of the sale. In fulfilment of an old promise, Henry Chaplin bought his wonderful collection of brandy—52 dozen bottles, some of it dating back to the early eighteenth century. " If anything happens to me, Harry, you will look after my brandy," he had said.

Mr. Chaplin had also kept an interesting record of the famous quarrel and duel between Lord George Bentinck and Squire George Osbaldeston, the particulars of which he appears to have received from Mr. George Payne, who was on intimate terms with both parties to the dispute:

Mr. Osbaldeston and Mr. Horatio Ross1, the famous deer-stalker, were probably the two most celebrated pistol shots in England of their day. At that time letters were usually sealed with small round wafers, which were made by stationers in twelve different colours. A not uncommon practice, I was told, in pistol shooting, was to stick these wafers on a target in a straight line, one above the other about two inches apart, and when the word of command was called out, in quick succession the marksmen had to fire at the colour named. Each of these men was frequently able to hit each of the wafers in succession without a single miss.

Note 1. See p. 255.

Lord George, on the other hand, I believe, was only a moderate shot at best, although in years to come, during the debates on the Corn Laws, he was frequently either called out by offended opponents, or called out others himself. Indeed, old General Peel1, who was a contemporary—and, though a brother of Sir Robert, a member of the Tory Party, —used to tell me that there was seldom a big debate on the Corn Laws that he had not to spend a considerable time in either taking or receiving challenges on account of Lord George, who was very outspoken about his opponents.

Note 1. Jonathan Peel [General] was the fifth son of the first Sir Robert Peel, but a man possessing more geniality than his father and more manners than his eminent brother. At the secession of the Peelites he remained staunch to his Party and served as Secretary of State for War under Lord Derby in 1858 and 1866. He was devoted to racing. In 1824 he ran second in the Oak' to Cobweb with his mare Fille de Joie, whom he had bred; and he won the Derby of 1844 with Orlando, after the disqualification of Running Rein.

I remember one duel being fought in my own time between the late Sir Michard Bulkeley and Colonel Armitage, but they had to fight in France. There were three other instances also, where people were called out and would have had to fight had the causes of the quarrel not been settled.

The case I speak of arose from the running of Mr. Osbaldeston's horses at Heaton Park in Lancashire—(which was at that time the property of Lord Wilton, so well known in Leicestershire, and ranked as the Goodwood of the north of England)—they had run with two different horses of Lord George's in two different races, I believe on successive days, but at all events during the same week. In the first race Osbaldeston's horse, which was backed apparently for a good deal of money, ran nowhere and was badly beaten.

The next day that he ran he had to meet another of Lord George's horses, against which, according to the running of Mr. Osbaldeston's horse the previous day with Lord George's other horse, he could have no chance. Lord George, who had the reputation of being a first-rate judge of form, and in particular of that of his own horses, was in the habit, according to Payne, of occasionally laying against horses which in his opinion could have no chance, as well as backing those he thought would win. Accordingly, when he found Mr. Osbaldeston's horse, which had been so badly beaten on the first day, being freely backed on the second, he laid £400 against him.

He was more than surprised when this horse of Mr. Osbaldeston beat his own horse, who on the previous running had any amount of weight in hand, and won in a canter. He said nothing about it then, but told his commissioner not to pay Mr. Osbaldeston's claim for £400 on the following Monday at Tattersall's. In those days owners and backers of horses generally attended the settling at Tattersall's themselves, which was situated then on what is now the site of St. George's Hospital.

Nothing happened on the first Monday or the second, but on the third Mr. Osbaldeston went up to Lord George and said, "My lord, you appear to have forgotten that you owe me £400 for Heaton Park and haven't put it in your account." Lord George replied, "Do you mean to say, sir, that you dare to ask me for the money for that robbery—for it was a robbery, and you know it."

Mr. Osbaldeston never wanted pluck, whatever else he may have lacked, and he sent him a challenge at once. Everybody was aghast, for Mr. Osbaldeston was furious at the insult, and if the duel was fought it was almost certain he would kill Lord George.

Lord George's friends did everything they could to induce him to say something which might prevent it, but in vain. At last a certain number of them got together and asked him to allow them to write a letter which might be sufficient to prevent the duel. To this he agreed, but only on condition that it was brought to him to see and was not to be sent without his permission. It was arranged he should see it at White's Club the following afternoon, the duel being early the next morning. It was duly handed to him the next day at White's, and this, according to George Payne, was what happened.

He read it slowly and carefully all through, and he read it slowly through once again. After that he deliberately tore the letter up into small pieces and he threw them into the waste-paper basket. " No," he said, " it's no use. It was a robbery. D—n the fellow, I hate him, and I won't withdraw a word."

Every one was in despair and considered him as doomed. But it didn't appear to affect him in the least.

The matter, however, didn't end there. Payne, as I have said, was an intimate friend of both. In later days at Goodwood, when Lord George gave up racing for politics after the great betrayal by Sir Robert Peel, it was Payne who first took over the whole of his racing stud with all its liabilities, for £10,000, with the right, however, of paying forfeit ( £300) next day if he so desired after looking into them. As a matter of fact he paid forfeit.

Payne was also intimate with Mr. Osbaldeston, who was Master of the Pytchley Hounds certainly once, and I think twice, in Northamptonshire, where Payne had a house and a fine property of his own at Sulby, and was also at one time Master of the Hounds himself. He determined to see Osbaldeston that night, and knew exactly where to find him, at the Portland Club, where he played whist every day. Thither he repaired that night some time after twelve o'clock.