Modern Era

Modern Era is in Books.

Books, Modern Era, Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society

Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society 3rd Series

Books, Modern Era, With Mounted Infantry in Tibet by W J Ottley

Books, Modern Era, India and Tibet by Francis Younghusband

Books, Modern Era, The History of the Fanshawe Family by H C Fanshawe 1927

Books, Modern Era, A Dictionary of London

A Dictionary of London was originally published by H Jenkins LTD, London, 1918.

A Dictionary of London C

In Cornhill opposite the north end of Change Alley and the eastern side of the Royal Exchange.

Shown in Leake's map, 1666.

Stow tells us that after the year 1401 a cistern was made in the Tun upon Cornhill for water brought from Tyburn, and that from this time it was known as the Conduit upon Cornhill (S. 189, 192).

It is referred to in John Carpenter's letter describing the triumphant entry of Henry VI. into London in 1432 as "Conductum aque sphaericum in dicto vico" (i.e. in "vico Sancti Petri de Cornhille") (Mun. Gild. Lib. Albus, III. 461).

Enlarged by Robert Drope in 1475 with an east end of stone and castellated (S. 192).

"Tonne in the Conduitt" mentioned in Churchwardens' Accounts, St. Michael Cornhill (Overall, 190).

Sixty houses near the Conduit were pulled down in 1565 for the erection of the Royal Exchange (Three 15th Cent. Chron. p. 135).

It was burnt in the Fire and not rebuilt, as it was then regarded as an impediment to traffic (Wilkinson, I. 9).

Conduits.

In the 13th century the population of London had so much increased that the supply of water from wells had become inadequate and liable to contamination, and it had become necessary to seek for fresh sources of supply outside the City area.

The western suburbs and surrounding villages were rich in streams and wells, and it was arranged about 1237 to bring a supply of water in pipes of wood from Tyburn to the City. In the 15th century a further supply was obtained from Paddington.

For the purpose of conserving this supply and making it available for public use, conduits and cisterns were established at suitable points in the City to which the citizens could have access, and bequests were frequently made by the citizens in later times towards the repair and maintenance of these conduits.

Besides the conduits and waterworks, the City was also until a recent period supplied with water from springs, and Strype mentions, as being especially excellent, pumps at St. Martin's Outwick; near St. Antholin's Church; in St. Paul's Churchyard and at Christ's Hospital.

Many of the conduits described by Stow had been removed before 1720, as being a hindrance to traffic, viz.: The Great Conduit at the east end of Cheapside; The Tun upon Cornhill; The Standard in Cheapside; The Little Conduit at the west end of Cheapside; The Conduit in Fleet Street; The Conduit in Gracechurch Street; The small Conduit at the Stocks Market; The Conduit at Dowgate.

Victoria County History - Buckinghamshire

A History of the County of Buckingham

A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 3

Books, Modern Era, Sussex Record Society 1903

Bishop Praty's Confirmations of Monastic Elections and Benedictions of Newly Elected Abbots and Priors

Resignation oe the Prior de Calceto.

In the Name of God, Amen. I, brother John Baker, Prior of the Priory of the Conventual Church of St. Bartholomew de Calceto of the Order of St. Augustine [Map] of the Diocese of Chichester, willingly and heartily, from certain true and lawful causes moving me thereto, [desire] to be entirely relieved from the cure and rule of the Priory and from the state and dignity of Prior of the same place, and I resign the same my Priory de Calceto and the state and dignity of Prior of the same into your sacred hands, reverend Father and Lord in Christ, Lord Richard by the grace of God Bishop of Chichester, Diocesan of the place, and all right in the same state or dignity of Prior belonging to me heretofore in any manner I yield up and resign, and from their possession in deed and word I altogether retire in these writings.

This above-written resignation was made in a certain ground floor room outside the door of the hall within the Manor of the Lord Bishop of Chichester at Aldyngbourne on May 9th, 1439, in the second Indiction, in the ninth year of the Pontificate of the most holy Father and Lord in Christ, Lord Eugenius IV., Pope, in the presence of Master Thomas Boleyn (age 39), Sir John Kyngeslane, Chaplain, John Fulbourne and others.

And immediately after the reading of the schedule the said reverend Father the Bishop of Chichester admitted the aforesaid resignation, the same witnesses being present, and I, William Treverdow, notary public, also being present.

And it is to be remembered that on the Wednesday, in the week of our Lord's Passion, about 10 o'clock before nones, namely, on March 23rd in the year above written, in the third Indiction, in the 10 th year of . . Pope Eugenius IV., the aforesaid Thomas Shorham, Abbot, as he asserted, elected and confirmed of the Monastery of Begham . . appeared before . . Eichard . . , Bishop of Chichester, in the Chapel situated within his Palace of Chichester, and asked and instantly begged the same Eeverend Father, his Diocesan, that he would deign to distinguish him with his gift of Benediction in the Church's accustomed form. To this the said Eeverend Father said that he willingly would. And subsequently, arrayed in Pontifical vestments

and decorations, he celebrated in a low voice the Mass of the Holy Spirit. And in the course of the solemnities of the Mass he conferred on the aforesaid brother Thomas elected, as is stated above and con- firmed, the gift of Benediction used and accustomed by the Church in such cases. Which done, the said brother Thomas made his obedience to the said Eeverend Father in the form which follows:-

In the Name of God, Amen. I, Thomas Shorham, Abbot of the Monastery of Begham, of the Premonstratensian Order of Chichester Diocese, elected and confirmed, profess, &c. [as on p. 155], . . being present then and there the venerable and discreet Master Thomas Boleyn (age 39), LL.B., Edward Brugge, John Kyngeslane, Chaplains, John Fulborne, John Halswell, 'scutifers,' and very many others in a large crowd.

Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society

Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Volume 40

Books, Modern Era, Lifes Ebb And Flow by Frances Countess of Warwick

1929. Life’s Ebb & Flow By Frances, Countess Of Warwick (age 67). "I scarcely count these things our own".

Books, Modern Era, Royal Ascot

Royal Ascot. Its History and Associations. By George James Cawthorne and Richard S Herod. 1902.

The reign of George III. saw the institution of the " Classic " races. The Doncaster St. Leger was established by Colonel St. Leger (age 43), who lived near Doncaster. In 1776 he proposed a sweepstakes of 25 guineas each for 3-year-old colts and fillies over a two-mile course, which was won from six competitors by the Marquis of Rockingham's (age 46) filly, Allabuculia.

In 1778 a dinner was being held at the Red Lion Inn, Doncaster, on the entry day of the races, and the Marquis of Rockingham (age 46) then proposed that the sweepstakes suggested by Colonel St. Leger (age 43) two years previously should be run for annually, and bear the name of the founder. In this year it was won again by a filly, called Hollandaise, belonging to Sir Thomas Gascoigne (age 30).

Books, Modern Era, The Parish Register of Halifax

The Parish Register of Halifax Preface

In Aug 1551 the sweating sickness swept over the parish. Between Aug. 2nd and 24th, of 45 deaths, 42 were due to this visitation, which seems to have subsided almost as quickly as it arose, only two deaths being recorded as due to this cause after the latter date. But the most notable feature in this part of the Register is the entry of the burials of the bodies of the criminals who had been gibbeted. They are 29 in number, but include no names hitherto unknown, although the first of them is not given in the latest list.1

Note 1. The Yorkshire Coiners (p. 280) by H. Ling Roth.

Books, Modern Era, The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell

The Scarlet Tree being the second volume of Left Hand Right Hand. An Autobiography by Osbert Sitwell (age 66).

The Scarlet Tree by Osbert Sitwell Chapter 2

The Scarlet Tree. Chapter 2. Retreats upon an Ideal. Though in the next chapter I shall have to revert for a few pages to my early school-days, in order to sum up their effect, in mind and body, upon at least one boy, here we will leave the scene of them for a while. First, however, I must produce a letter, written in my third term, because it gives, despite cacography, indications of character, in others no less than in myself, and serves as a kind of preface for the chapter that follows .... Victor, to whom it makes reference, was; I must explain, my cousin, exact contemporary and, at that time, chief foe.

04 Nov 1903

Darling Mother,

I hope you are quite well. Do let me know your adres in Naples. The aples have arrived. Thank you so much.

I am better but wish I had no teeth. They are aching as hard as they can go.

Any chance of our going to Londesborough or Blankney for Christmas, do find out first if Victor will be there, because I should not enjoy it if he was. I am also afraid I shall be shy there, and that they will make a fuss if I do not taulk all day like when I was at Blankney last Christmas. Please write to me at once when you get my letter. I do miss you. - Your loving son

Osbert.

P.S. Please let me know about Blankney.

Blankney stood, a dead weight in the snow, pressing it down with a solidity pronounced even for an English country-house. For us it loomed large at the end of each year, and the roads of every passing month led nearer to it, an immense stone building, of regular appearance, echoing in rhythm the empty syllables of its name. The colour of lead outside, its interior was always brilliantly lit, its hospitable fires blazing, flickering like lions within the cages of its huge grates, so that it seemed to exist solely as a cave of ice, a magnificent igloo in the surrounding white and mauve negation. What was the purpose of these spacious, comfortable tents of snow, that appeared all the more luxurious because of being picthed in so desolate and empty a whiteness, and that were full of a continual stir? .... Ease, not beauty, was their aim ; for beauty impeaches comfort, disturbing the repose of the body with questions of the spirit and, worse still, pitting the skeleton against its encasing flesh .... So there were few fine pictures in the large rooms, leading one into the other, only perhaps one, the Lawrence of Elizabeth Denison, Marchioness Conyngham, founder of the family. There were pleasant portraits, such as that by Sir Francis Grant of Lord Albert Conyngham, her son, surrounded by a few pieces from the celebrated and superb collection he had formed, now, except for jewels and plate, all dispersed. Here and there, ivory mirrors and other sumptuous objcects, given by King George IV to Lady Conyngham, and bearing on them the Royal Arms, survived; but for the most part the rooms contained little to look at. The Saloon, chief sitting-room, was long and rather high, full of chairs and sofas, piled with cushions (the aim of which was plain, to get you to sit down and prevent you from getting up and so to waste your time), with tables with many newspapers lying folded on them, and the weekly journals, and green-baize card-tables, set ready for you to play. The light-coloured, polished floor had white fur rugs, warm enough and yet suggesting the pelts of the arctic animals that must prowl outside: but to counterbalance such an impression, there were tall palm-trees, and banks of malmaisons and carnations and poinsettias, a favourite flower of the time, a starfish cut out of red flannel, and the standard lamps glowed softly under shades of flounced and pleated silk that mimicked the evening dresses of the period. There were writing-tables, too, and silver vases, square silver frames, with crowns in silver poised above them, containing the photographs of foreign potentates, posing in their full panoply of flesh as Death's Head Hussars, or with flowing white cloaks and firemen’s helmets, their wives, placid, with folded hands — silver inkstands and lapis paper-weights, and near the fire-place, two screens, cut out of flat wood, and jocularly painted a hundred or so years before, to represent peasants in costume! On one wall hung a large portrait by a fashionable artist, of my aunt balancing her second son in an easy position near or on her shoulder. There were many silver cigarette-boxes ash-trays and boxes of matches of every size from giant to dwarf. Certainly the rooms had a supreme air of modish luxury, and no quality so soon comes to belong to the past — for the skeleton outlives its flesh .... What more do I recall: the broad, white passages — out of which led the bedrooms — , so thickly carpeted, and the white arches, on one side of the corridors, looking down on hall and staircase ? What else ? The warmth, the fumy, feathery scent of logs and wood ash, and a lingering odour, perhaps of rosewater, or some perfume of that epoch, a fragrance, too, of Turkish cigarettes .... And for a moment, I see the women, their narrow waists and full skirts, and the hair piled up, with a sweep, on their heads, or surrounding it in a circle. Above all, I hear the sound of music.

Sometimes a string band would be playing in the Saloon — Pink or Blue Hussars insinuating whole Hungarian charms of waltzes, gay as goldfinches — but more often the tunes would be ground out by innumerable mechanical organs. There seemed to be one or two in every passage. You turned a handle, and these vast machines, tall as cupboards — objects which, since they have been superseded by gramophone and radio, would today constitute museum pieces — , were set in motion, displaying beneath their plate-glass fronts whole re- volving, clashing trophies of musical instruments, violins that shuddered beneath their own playing, frantic drums, tam- bourines that rattled themselves as at a seance, and trumpets that sounded their own call to battle. I scarcely recollect the tunes they played, overtures by Rossini and Verdi, and — of this I am sure — some of the music of Johann Strauss’s Fledermaus. The warm golden air of these rooms trembled perpetually to martial or amorous strains, yet they are not in memory more characteristic of the place than are the sounds of the family voices, variations, that is to say, of the same voice. For this house was the meeting-ground of all the generations surviving of my mother’s family, and these tones were the particular seal and link of it, containing, as they did, a special quality of their own, lazy and luxuriant, sun-ripened as fruit upon old walls. They seemed left over from other centuries, even those of the youngest, and former ways of speech still persisted among the older members of the family, tricks of phrase that might have seemed an affectation ; but then, my relatives on this side did not read much, and so these ways were traditional. All learning came to them by word of mouth. And, at the same time that I hear again these voices, and the music, I hear, too, something scarcely less typical, the quarrelsome, rasping voices of packs of pet dogs, demanding to be taken out into the cold air, their bodies surrounding the feet of the women of the house, as they walked, with a moving, yapping rug of fur, just as in frescoes clouds are posed for the feet of goddesses. And as, at last, these creatures emerge into the open air, they bark yet more loudly, jumping up, lifting their ill-proportioned trunks to the level of their mistresses’ knees.

How far this passion for dogs, shared by men and women alike, was a family trait, or merely indicative of class or period, I am not aware, but on occasion, and particularly in my grandparents’ time, it reached to the strangest level of fantasy, to a height of distorted exaggeration. Thus, an old friend, writing to me lately, gives an instance of what I am trying to indicate, in an account of a visit he paid to my grandfather and grandmother at Londesborough in the ’nineties: " I rernember ", he says, " arriving at the station one dark winter’s evening. When I entered the park, I was surprised to hnd it brilliantly illuminated, lamps being hung all up the fine old trees. I wondered if there could be taking place that night a county ball, of which I had not been warned. After the festive air prevailing, it was, though, something of a shock when I reached the house, to find all the family, more or less, in tears, and I could not imagine what could have happened and what could explain all these various contra- dictory phenomena. It was, therefore, a relief to learn finally the cause ; a pet dog, who had escaped and gone off hunting in the morning, had not yet returned. The lamps had been ht to show him his way home." ... A similar devotion still inspired the owners of these dogs we have noticed, their arking attending the coming-in or going-out of any member oi the family, like the fanfares of heralds.

The music came out of the door, as it was opened, in a loud gust, stronger than the barking of dogs, and the intense cold for a moment refined it, gave it increased clearness, until its reverberations muffled themselves in the snow The house, the church, the stables, the kennels formed a dark and solid nucleus, a colony in this flat landscape that did not exist: the village was somewhere near, yet out of reach as the equator — perhaps it was interred under the snow. For an hour at midday the cold yellow daylight poured down, else always it was mauve against the electric light. Snowflakes scurried past on the east wind, that lived so conveniently close, in the sea, just beyond the edge of the negation ; of which all one knew was that somewhere in it, about eleven miles away, stood the ancient city of Lincoln. This town shone, indeed, in my imagination, as a kind of Paris, a Ville Lumiere, beckoning across the plain. But until it was reached, there was nothing, neither hills, nor mounds, nor mountains, nor trees — nothing except stretches of flat whiteness for hounds to run over, or occasional gates or barriers of twigs for red- coated, red-faced men to set their horses at.

Nearer, in the park, and in what must have been the meadows beyond — but until a few years ago I never saw Blankney at another season, so could form no idea of the country buried under this enveloping white shroud — were many enormous pits, containing whole armies of Danish invaders. ... Of this my father informed me, for, to tell the truth, he found himself, had he permitted the existence of such a word, bored, in a house where all the interests were of a sporting nature, and, in consequence, called his bluff. Moreover, it was made worse for him by the fact that the remainder of the guests enjoyed themselves to the same extent as he was miserable. Pure self-indulgence. But he could always find solace, he was thankful to say, in thinking over historical associations — so long as they were of the correct period. And here he was fortunate, for the great slaughter, of which these pits were — if only you could see them — the abiding sign, had taken place between a.d. 700 and 800, and nothing much had occurred in this district since then to spoil the idea of it. Therefore, he could always take refuge with the Danish dead, always cause his blood to tingle, by telling me how these huge excavationSj filled with bodies of warriors, killed by the retreating Saxons some eleven hundred years before, had been dug out, and how^ they had been covered first with the branches of trees, on which the earth was then shovelled — that accounted for the mounds. The very thought of it, in the American phrase, made him "feel good". With gusto he described the brave invaders, their bronze helmets and primitive axes, until for the first time I visualised that Wagnerian world of firemen armoured in bronze, with flowing moustaches, and long hair, led by bearded, resonant voiced kings, potbellied, who pledged their cave-loves in blood drunk from the skulls of their enemies. It was not, I found, a world which I much liked: but my father, I recollect, used to declare that if only the members of my mother's family were more intelligent, they would spend their whole time in digging up the bones, instead of in hunting, shooting and going to circuses. He would also tell me — this, I think, in order to make himself feel morc at home in a house given to relatives by marriage - that Blankney had been "held" in the twelth century by the Deincourts, a Norman family of whom, through the Reresbys, we were the representatives, entitled to quarter their arms. (The Londesborough escutchcon he considered, he owned, as shameful, a "horrid eighteenth-century coat, all wrong in heraldry".)

As for the old, though they would try to be amiable to the young, by now crossness had settled in their bones. The women seemed always to live on for ten years or more after their husbands, and dowagerdom possessed its own very real attributes. Moreover, they made their age felt through the medium of many devices. It was not, after all, merely that they looked old ; on the contrary, they gloried in their age and the various apparatus of it, and indulged in a wealth of white wigs and fringes, sticks, ebony canes and Bath-chairs, while, as for strokes, these were de rigueur from sixty onwards! In fact, it was a generation which, unlike the next one, did not know how to grow young gracefully .... Thus, my grandmother Londesborough (age 71) was seldom now to be seen out of a Bath-chair, though she was still able to exercise her charm on us without effort, and equally to deliver the most portentous snubs when she wished it .... Nevertheless, her world had changed — for though she had been train-bearer to Princess Mary of Cambridge, afterwards Duchess of Teck, at Queen Alexandra’s wedding to King Edward, and had stayed at Windsor for the ceremony, which took place in St. George s Chapel there, and though, too, she and my grandfather had always belonged to the pleasure-loving, yet she was never Edwardian in the sense that her son and daughter-in-law were. She possessed a stricter outlook, a more severe sense of duty, and all the rather naive, unsophisticated courage of the Victorians, as well as sharing their genuine belief in the conventions.

In general, each Christmas [at Blankney Hall] the representatives of the older generation were the same, invariably numbering in their company my grandmother [Edith Somerset Countess Londesborough (age 69)], her brother-in-law [Arthur Walsh 2nd Baron Ormathwaite (age 80)] and sister [Katherine Somerset Baroness Ormathwaite (age 73)]. Lord and Lady Ormathwaite, and Sir Nigel (age 77) and Lady Emily Kingscote (age 72). Lord Ormathwaite was even then over eighty — he lived to be ninety-three. Both he and his wife were of a deeply religious nature (it was very noticeable how much more devout were the old than their sons and daughters), and one of the favourite amusements of the children, I remember, was to hide in the broad passage outside the bedroom of this old couple, and listen to the vehement recitation of their lengthy and extremely personal prayers. Another frequent Christmas visitor, until her death in 1903, was Adza Lady Westmorland, who belonged to the same epoch, being the mother of my aunt, and a sister to the 8th Duchess of Beaufort and Lady Emily Kingscote (age 72). She was a godchild of Queen Adelaide, as was her nephew the Duke of Beaufort (age 60)1. Adza Lady Westmorland, indeed, came of a family much devoted to Queen Adelaide, since she was the daughter of that Lord Howe — the 1st Earl Howe — whose singular conduct at the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, when King William IV was living there, had roused the malicious interest of Charles Greville. Lord Howe, a handsome young man "with a delightful wife", hovered dotingly round Queen Adelaide whenever she was in the room, remained gazing at her with eyes full of love and admiration, and behaved altogether, the diarist relates, as though "a boy in love with this frightful spotted majesty" .... Adza Lady Westmorland, as I remember her, was a very old lady in a Bath-chair, who wore a black dress and a large, shady black hat. But she still retained her wonderfully exquisite manners and her great charm, for both of which she had been celebrated. In her time, she had been responsible for several small social innovations for women, such as wearing tweeds and smoking cigarettes.

As for the young, they were for the most part the same as those we saw a few years before at Scarborough: my cousins, Raincliffe — Frank — , and Hugo and Irene Denison, Veronica and Christopher Codrington, Enid Fane (age 13) and her brother, Burghersh (age 14) — who was my particular friend and companion at that time, in the same way that Victor was my enemy elect — , Marigold Forbes, and other young relatives. Entertainments were provided for them — and, as we shall see in a moment, by them — with regularity. Presents were I do not know how much the old or the young plentiful .... enjoyed the parties — scarcely as much as the members of the ruling generation, I should say ; to the old, certainly, these Christmas festivities brought a feeling of sadness, of deposition.... Among the children, I am sure that the child who felt least happy, an alien among her nearest grown-up relations, was my sister. Acutely sensitive, and with her imagination perhaps almost unduly developed by the neglect and sadness of her childhood since she was five, she could find no comfort under these tents. She loved music, it was true — indeed, where music is, there, always, is her home but the music of this house meant little to her, and the formal conversation between children and grown-ups, even if they were trying to be kind, frightened and bored her ; while she did not care for the machinery of the life here ; the continual killings seemed to her to be cruel, even insane. She ought to have asked to go out with the guns, even if she herself did not shoot ; she might at least have attended a meet. And, if anything, my father's inclination to nag at her on the one hand, my mother's, to fall into ungovernable, singularly terrifying rages with her, on the other, because of her non-conformity, seemed stronger when there were people, as here, to feed the fires of their discontent, and other children to set a standard by which to measure her attainments. "Dearest, you ought to make her like killing rabbits," one could hear the fun brigade urging on my mother. But while my father was angry with his daughter for failing to comply with another standard — his for not having a du-Maurier profile, a liking for "lawn-tennis" or being able to sing or play the zither after dinner (it did not affect him that his wife's relations would have been very angry if she had attempted to play the zither at them), he was also disappointed on another score. She seemed far less interested than I was — or even Sacheverell who was only six or seven — in his stories about the Black Death (a subject he had been "reading up" in the British Museum), and she seemed to have no natural feeling for John The Victorians, Stuart Mill's Principles of Political Economy .... I think, appreciated Edith more than did the Edwardians. But Irene was the particular focus for grown-up attention and affection, not bccausc she was the only daughter of the house, but because the delicate loveliness of her appearance, with her fine skin and huge, dark-blue eyes, and a certain kind serenity, unusual in a child of her age, made everyone want to spoil her. But it was in vain she remained absolutely unspoilt, gentle, amiable, full of kindly fccling towards the whole world.

Note 1. Henry Adelbert Wellington FitzRoy, 9th Duke of Beaufort (age 60) (b. 1847), was named Adelbert after Queen Adelaide, and Wellington after the Iron Duke, his godfather and his father’s great-uncle. He died in 1920. His late Royal Highness the Duke Connaught (1850—1942) was one of the two last surviving godsons of the Duke of Wellington, the other and ultimate being the 4th Marquess of Ormonde (age 58) ( 1849-1943).

That was the last time I saw Blankney — except once more, in a dream, a singular incident which I will relate. And since it concerned my cousin Hugo (age 42), whose marriage I had attended that summer afternoon some two years before, I must first explain that though we had always been friendly when we met, of recent years I had not seen much of him, for I was often abroad, while all his interests, hunting and racing, were of a different kind from mine and tended to keep him in the country .... It occurred in the early spring of 1937, when I was living in a villa near Vevey, on the Lake of Geneva. One night I was very restless, waking up at about two, and finding myself unable to get to sleep again for hours Eventually, about 6.30 in the morning, I fell into a long, troubling and involved dream, which yet did not the realm of nightmare. In it, I was in the Saloon at Blankney again, and Hugo (age 42), the owner of it, was talking to me very urgently. His words were simple enough, but laden with a weight of presage, and of sad and menacing feeling, and I knew that in his last sentence he was conveying to me something importance. He said, "There will be a party here at Blankney in ten days' time. All the relations are coming. They arrive by special train in the morning, and leave by special train in the afternoon." .... Then I woke up ; to find I was being called by my servant. He handed me The Times of the previous day — it always arrived in Vevey twenty-four hours after it had come out in London. I sat up, still unreasonably distressed, opened the paper — and the first heading that caught my eye as I did so was Serious Illness of Lord Londesborough .... It was impossible to misapprehend so clear a portent, although in my dream seen in reverse: but I still hoped that I might be wrong, because I knew that all the members of Hugo's (age 42) family had hitherto been buried at Londesborough, and this detail, so incorrect, seemed to falsify my reading of it. Howbeit, I was still so much oppressed by the feeling of the dream, that I told two friends, who were staying with me at the time, of it and of the sequel in the paper .... For a while it appeared that Hugo (age 42) was better, but a week later he died, and three days after that was buried at Blankney.

Books, Modern Era, 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica

1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica Volume 24

1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica Volume 24 Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft

1911. SHELLEY, MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT (1797–1851), English writer, only daughter of William Godwin and his wife Mary Wollstonecraft, and second wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, was born in London on the 30th of August 1797. For the history of her girlhood and of her married life see Godwin, William, and Shelley, P. B.

1816. When she [Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 18)] was in Switzerland with Shelley and Byron (age 27) in 1816 a proposal was made that various members of the party should write a romance or tale dealing with the supernatural. The result of this project was that Mrs Shelley wrote Frankenstein, Byron the beginning of a narrative about a vampyre, and Dr Polidori (age 20), Byron's physician, a tale named The Vampyre, the authorship of which used frequently in past years to be attributed to Byron himself.

Frankenstein, published in 1818, when Mrs Shelley (age 20) was at the utmost twenty-one years old, is a very remarkable performance for so young and inexperienced a writer; its main idea is that of the formation and vitalization, by a deep student of the secrets of nature, of an adult man, who, entering the world thus under unnatural conditions, becomes the terror of his species, a half-involuntary criminal, and finally an outcast whose sole resource is self-immolation. This romance was followed by others: Valperga, or the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (1823), an historical tale written with a good deal of spirit, and readable enough even now; The Last Man (1826), a fiction of the final agonies of human society owing to the universal spread of a pestilence—this is written in a very stilted style, but possesses a particular interest because Adrian is a portrait of Shelley; The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830); Lodore (1835), also bearing partly upon Shelley's biography, and Falkner (1837). Besides these novels there was the Journal of a Six Weeks Tour (the tour of 1814 mentioned below), which is published in conjunction with Shelley's prose-writings; and Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840–1842–1843 (which shows an observant spirit, capable of making some true forecasts of the future), and various miscellaneous writings. After the death of Shelley, for whom she had a deep and even enthusiastic affection, marred at times by defects of temper, Mrs Shelley in the autumn of 1823 returned to London. At first the earnings of her pen were her only sustenance; but after a while Sir Timothy Shelley made her an allowance, which would have been withdrawn if she had persisted in a project of writing a full biography of her husband.

In 1838 she [Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 40)] edited Shelley's works, supplying the notes that throw such invaluable light on the subject. She succeeded, by strenuous exertions, in maintaining her son Percy at Harrow and Cambridge; and she shared in the improvement of his fortune when in 1840 his grandfather acknowledged his responsibilities and in 1844 he succeeded to the baronetcy.

She [Mary Godwin aka Shelley (age 53)] died on the 21st of February 1851. [Note. Some sources state 01 Feb 1821]

Books, Modern Era, An Innkeepers Diary

Doris Chapman (age 27)

A most pretty and remarkable tall girl, Doris Emerson Chapman, with hips up to her armpits, upon which she rests her hand, walking or standing, was brought here to lunch by one of the odd Pete Brown family, where she paints curved-backed shire horses, in face herself rather horse. Her theory is that children needn't be told by their parents what is right and wrong, because they know it themselves instinctively, 'I knew perfectly well when I was being mean or loathsome long before my parents told me. All a child wants is sympathy.' Let her at once drop the shire horse and start a rare and happy stud of her own.

Books, Modern Era, Diary of Virginia Woolf

Friday 27 May 1932. Last night at Adrian's evening. Zuckerman on apes. Doris Chapman (age 29) sitting on the floor.9 I afraid of Eddy coming in—I wrote him a sharp, but well earned, letter. Adrian so curiously reminiscent—will talk of his school of Greece of the past as if nothing had happened in between: a queer psychological fact in him—this dwelling on the past, when there's his present & his future all round him: D.C. to wit, & Karin coming in late, predacious, struggling, never amenable or comforting as poor woman no doubt she knows: deaf, twisted, gnarled, short, stockish—baffled, still she comes. Dick Strachey. All these cold elements of a party not mingling. L. & I talk with some effort. Duncan wanders off. Nessa gone to Tarzan.10 We meet James & Alix in the door. Come & dine says James with the desire strong in him I think to keep hold of Lytton. Monkeys can discriminate between light & dark: dogs cant. Tarzan is made largely of human apes. People have libraries of wild beast 'shots' let out on hire.

Note 9. Solly Zuckerman (b. 1904 in S. Africa), zoologist and from 1928-32 Demonstrator in Anatomy at University College, London, had just published The Social Life of Monkeys and Apes. Doris Chapman, with whom Adrian had fallen in love, was a painter currently showing her work at the Wertheim Gallery.

Note 10. Richard (Dick) Strachey (1902-76), writer, elder son of Lytton's brother Ralph. The 'screen sensation' Tartan the Ape Man, with Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O'Sullivan, was showing at the Empire Leicester Square.

Monday 13 Jun 1932. Back from a good week end at Rodmell—a week end of no talking, sinking at once into deep safe book reading; & then sleep: clear transparent; with the may tree like a breaking wave outside; & all the garden green tunnels, mounds of green: & then to wake into the hot still day, & never a person to be seen, never an interruption: the place to ourselves: the long hours. To celebrate the occasion I bought a little desk & L. a beehive, & we drove to the Lay; & I did my best not to see the cement sheds. The bees swarmed. Sitting after lunch we heard them outside; & on Sunday there they were again hanging in a quivering shiny brown black purse to Mrs Thompsett's tombstone. We leapt about in the long grass of the graves, Percy all dressed up in mackintosh, & netted hat. Bees shoot whizz, like arrows of desire: fierce, sexual; weave cats cradles in the air; each whizzing from a string; the whole air full of vibration: of beauty, of this burning arrowy desire; & speed: I still think the quivering shifting bee bpg the most sexual & sensual symbol. So home, through vapours, tunnels, caverns of green: with pink & yellow glass mounds in gardens— rhododendrons. To Nessa's. Adrian has told Karin that he must separate She demurs. They are to start separate houses, he says, in the autumn.

Last week was such a scrimmage: oh so many people: among them Doris [Chapman] (age 29) & Adrian: she like a dogfish: that circular slit of a mouth in a pale flesh: & an ugly rayed dress: but said by Nessa to be nice. Why the bees should swarm round her, I cant say. Now Vita rings up: may she & Harold dine tonight: then Ethel: I look ahead to my fortnights week end.

Friday 08 Jul 1932. And so I fainted, at the Ivy: & had to be led out by Clive. A curious sensation. Feeling it come on; sitting still & fading out: then Clive by my side & a woman with salts. And the odd liberation of emotion in the cab with Clive; & the absolute delight of dark & bed: after that stony rattling & heat & Frankie shouting; & things being churned up, removed.

I write this on a blazing morning, because L. is instructing Miss C[ashin]. how to arrange the books: so that I cant correct articles. "Every- where I look everything is hopeless.... Either the Northern Saga ought not to be here at all—or it ought to be in the other room.... (John is ill: publishing day yesterday; Harold drivelling snapping, when I hoped for 'serious criticism'—why go on hoping?) the whole of thats going over—Here are 3 things of Nature has no tune ofwh. we dont sell a copy a year..."4

Oh dear, I've twenty minutes to use; & cant 'correct' any more. What a fling I shall have into fiction & freedom when this is off! At once, an American comes to ask me to consider writing articles for some huge figure. And (hushed be this said) I sent Nessa a cheque for £100 last night: & Leonard gave his mother £50, & Philip [his youngest brother] £50. These are among the solid good things, I think: Nessa's £100 will buy her some release from worry, I hope: Clive saying they must spend £600 a year less. Roger to have his operation, said to be slight, tomorrow. Adrian fretted to death—almost to fainting in the street—must anyhow stumble in to Nessa's & ask for water & spend the evening—by the vagaries of his Doris (age 29). This is what Francis foretold: a girl of dubious morality, & to me like a codfish in her person. And there are fleas at M[onks].H[ouse].: to which we go; & black beetles here, & said to be mice also.

Note 4. The books referred to are The Northern Saga (1929) by E. E. Kellett and Nature Has No Tvne (1929) by Sylva Norman (HP Checklist nos. 198, 203). Harold Nicolson's review of V W 's and Hugh Walpole's Letters... appeared in the NS&N on 9 July 1932.

Books, Modern Era, Durham University Journal

Durham University Journal 1918 Volume 21

Books, Modern Era, Flintshire Historical Society

Flintshire Historical Society V5 1914

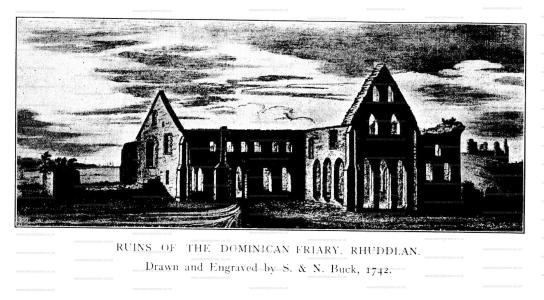

1742. Ruins of the Domincan Friary [Map], Rhuddlan. Drawn and Engaved by S & N Buck, 1742.

Books, Modern Era, The Life of Henry

The Life of Henry, Third Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare's Patron by Charlotte Carmichael Stopes. Cambridge At The University Press 1922.

The Life of Henry, Third Earl of Southampton Chapter 4 Proposals for Marriage

THE story of Southampton's life for the next few years has not been fully followed or understood. The present writer has sketched it in the preface to her edition of the Sonnets, in The Athenaum1 , and in her Shakespeare's Environment2. But much needs yet to be discovered. The guardianship of a royal ward at that time generally included what was technically called "his marriage," that is, the right to choose him a partner for life, to make all arrangements, and to receive a sum of money for the transaction. There were certain limitations as to rank, property, and suitability of the proposed lady, but mutual affection was rarely considered as a real or a necessary condition. Burleigh had been successful in marrying his children into noble families. He was very pleased when he wrote in his Diary that the Earl of Oxford wished to marry his daughter Anne. But it had been an unhappy marriage, and his daughter had died on June 5th, 1588. The careful statesman was now doing his best to ensure her daughter Elizabeth a happier life. She had been born on July 2nd, 1575, and was therefore of suitable enough age for Southampton. Burleigh's own wife, Lady Mildred, "fell asleep in Westminster" on April 5th, 1589, and was buried beside her daughter, the Countess of Oxford, in Westminster. Lord Oxford was careless as a family man, and Burleigh felt himself bound to be mother and grandmother to the girl, as well as grandfather. Now, he really liked his brilliant young ward, he trusted him, he approved of his property and the dwellings he would have to live in on his coming of age — a little ready money put into them as the bride's dower would make them quite satisfactorily comfortable to settle in for life. There is no allusion at any time to the inclinations of the young lady, but the matter had evidently been well discussed with the youth and with his immediate relations. They had agreed readily enough; the bridegroom elect's one idea was how to postpone decision.

Note 1. March 19th and 26th, 1898.

Note 2. p. 135.

Many writers have described Southampton as a lascivious youth; but there is not the slightest authority for such a statement. The facts, which have been twisted so as to support that opinion, are capable of a very different explanation, as will be seen hereafter.

We must remember that he had no evil predisposing tendencies from hereditary influences. His grandfather Southampton, whatever his other faults may have been, was noted for conjugal devotion. His father, it is true, had at the end of his disappointed life lost his early affection for his wife; but the only authority we have concerning him was that he had kept his vows of wedlock. His grandfather Browne was noted for the chastity of his thought, speech, and behaviour; he was indeed "a very perfect, gentle knight."1 In regard to his environment and training, Burleigh was a very safe guide in questions of morality, and he kept a watchful eye over the youth's motions for his own sake. Further, the young man was full of occupation. He had to read law at Gray's Inn to please his guardian; to make a figure at Court to please the Queen; to prepare for war in order to be able, if need be, to defend his country; and to study literature and the arts to please himself. So he had no temptation through idleness and ennui. Through all his interests there floated the memory of his College paper — "All men are incited to study through the hope of glory!" Since the death of his mother's relative and good friend, the Earl of Leicester, he had come more into contact with Leicester's stepson, the Earl of Essex. To Southampton Essex became the ideal knight, to whom he was willing to become esquire, or even page. Southampton's first love came in the shape of a man; his heart had no room as yet for love of woman. The youth had no active disinclination to the Lady Elizabeth, but he had a very strong disinclination to be fettered by any ties that did not leave him free to follow his own career. I do not know exactly on what terms he stood with Burleigh in regard to his granddaughter. Southampton may have said that possibly in some remote future he might learn to love her. His mother and grandfather evidently appreciated the advantages of this match. Theirs was but a new nobility compared with the Veres; their faith was a proscribed faith, and what a shield the Lord Treasurer could be to them against the most unpleasant consequences of conscientious devotion! Everything waited for the bridegroom-elect.

Note 1. Life of Magdalen Lady Montague.

Burleigh had become suspicious at his delay and feared a possible rival. He was not accustomed to be trifled with, and said so. The following straightforward letter from Sir Thomas Stanhope1 removed one of his causes of annoyance.

Ryght honorable, my humble duty premised, yt may please the same to understand, that of late I have been advysed by some of my friends about how it should be reported, that whilst I lay in London I sought to have the Earl of Southampton in marriage for my daughter; that I offered with her £3000 in money and £300 by yere for threescore yeres &c. Even true it is my Lord, that I have been beholding to my Lady of Southampton of long tyme, and so was I to my Lord her late husband during his lyf, and therfor bothe I and my wyfe did willingly our dutyes to see her when helth did permitte. Unto her Ladyship I appele yff she can apeche me of such simplicity or presumption as to intrude myselfe, or of the meaning of so treacherous a part towarde your honor, having evermore found myself so bound unto you as I have donne, I name it treachery, because I heard before then, you intended a matche that waye to the Lady Vayre (Vere) to whom you know also, I am akin. And my Lord, I confesse that talking with the Countess of Southampton thereof she told me you had spoken to her in that behalf. I replyed she should doo well to take holde of it, for I knew not whear my Lord her sonne should be better bestowed. Herself could tell what a stay you would be to him and his, and for perfect experience did teache her how beneficial you had been unto that Lady's father (though by hym litteU deserved). She answered I sayd well, and so she thought, and would in good fayth doo her best in the cause, but sayth she I doo not fynd a disposition in my sonne to be tyed as yett, what wilbe hereafter time shall trye, and no want shalbe found on my behalfe. I think once or twyse such like wordes we had and not to any other effecte, which I referre to her Ladyship's creditt to tell, who I thinke will no ways dissemble with your Honor in any cawse. For other part of honorable curtasyes both to my wyfe and dowghter I found myself much bownd to her for she bade us twyse to her house. And herself having occasion to come with my Lord her son to Mr Harvies' house of the warde, I did all that in me was to invite them to a simple supper at my house, being the next house adjoyning. And this, most honorable, hathe been all my proceeding that way, for yf it can be proved I made any attempt, or had the thought of anything that way, let me lose my credit with your Honor, and with all the world besydes, whiche truly I would not doe for the wourthe of the best marriage that ever my daughter shall have,' and yet Sir, I love her very well, and have given her advice accordingly, and would be as glad to bestowe her thereafter. Thus much my very good Lord, in discharge of my humble duty, I have presumed as beforesayd, and I shall (wish) yor Honor fynd me faytheful, in all the service I can, though not able to be thankeful as I desire. So praying for the continuance of yor good helthe and long lyfe I humbly take my leave. Shelf ord, this 15th of July 1590. Yor Honors humble cousin to command

(Sir) THOMAS STANHOPE

Note 1. D.S.S.P. Eliz. XXXIII. II.

The summer passed on, and the Queen did not reach Cowdray in her progress. Montague was invited instead to come and see the Queen at Oatlands [Map]1 Lord Burleigh was puzzled. He could not understand any intelligent young man in his senses refusing such an eligible offer. He had a good long talk over the matter with Lord Montague when he was at Oatlands, and gave him advice how to act when he had his grandson alone with him.

Note 1. Loseley Papers.

That nobleman wrote him as soon as he could after he got home.

My very good Lord2

As I well remember your late speach to me at Otelands [Map], touching my Lord of Southampton, so I have nott forgotten, so carefully as I might, and orderly as I could, to acquaint first his mother, and then himself therewithal, his Lordship late being with me at Cowdray. And being desirowse as orderly as I could, and as effectually as I was able to satisfye your Lordship of my knowledge in the matter, I thought itt best likely of, and I hope most liking to your Lordship to returne unto you what I find. First my daughter affirms upon her faith and honor that she is not acquaynted with any alteration of her sonnes mynd from this your grandchild. And wee have layd abrode unto hym both the comodityes and hindrances likely to grow unto him by chaunge; and indeede receave to our perticular speach this generall answer that your Lordship was this last winter well pleased to yeld unto him a further respite of one yere to enshure resolution in respecte of his younge yeres. I answered that this yere which he speaketh of is nowe almost upp and therefore the greater reason for your Lordship in honor and in nature to see your child well placed and provided for, wherunto my Lord gave me this answere and was content that I shoulde imparte the same to your Lordship. And this is the most as towching the matter I can now acquaint yor Lordship with. The care of his personne, and the circumstances of him, I can butt most effectually recommend to your Lordship's ruling. I mean God willing, and my dawghter also, at the beginning of the term to be in London, and then by your Lordship's favour will more particularly discourse with you, and will be sure to frame myself (God assisting me) to your Lordship's liking in this matter; and in the mean tyme require the continuance of your Lordship's very good will and opinion, and being lothe to be tediowse wish to your Lordship all honor health and happiness, From my house at Horsley igih September 1590, Your Lordship's assured to command.

Note 2. D.S.S.P. Eliz. xxxur. 71.

Lord Montague was probably at West Horsley, taking possession. His father had built it for his second wife, and had interwoven the arms of the Geraldines with his own, as he left it for her to dwell in; which she did.

She probably died in that house, and certainly was buried in that year1. She would be of a strange interest to the young Earl, for she was Elizabeth, Countess of Lincoln — not only "the fair Geraldine" of Surrey's Sonnets, but a connection by marriage of his own. While still a girl of 15, she had married the second Sir Anthony Browne (not by any means so old a man as her, or as his, biographers make out, as I have shewn in his Life2. Some time after his death she married Sir Edward Clinton, afterwards Earl of Lincoln, and they lived much at her dower house at West Horsley. As Viscount Montague's sister married her brother Gerald, Earl of Kildare, there was a double connection, and a certain family acquaintance. In her will she desired little expense in her funeral, as expenses do no good to the dead, and sometimes hinder the living. She left to the Queen her emerald ring; to the Earl of Kildare her best bed and other remembrances; "to the Lord Montague the six pieces of hangings of the Story of Hercules which usually hang in my great chamber at Horsley," and all her brewing implements and the brewing house there. To Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald of her Majesty's Pensioners and to her niece Lettice Coppinger she left remembrances, to her sister Margaret substantial aid; also "to my nephew Francis Ainger and his wife Douglas. To Sir William More (of Loseley) 5 pieces of hangings of the story of Abraham, and to my cousin George More 5 pieces at Horsley. To Sir Thomas Heneage one piece of plate worth £20, and to Mr Roger Manners one piece worth £i 5." She speaks of her daughters, but they must have been her stepdaughters. Her executors were to be her cousin Sir Henry Grey, her nephew Gerald Fitzgerald, and her nephew Francis Ainger; her overseers Sir Christopher Hatton and Lord Cobham.

Note 1. Beside her second husband, the Earl of Lincoln, in St George's Chapel, Windsor. All authorities are wrong in the date of her death, even G. E. C., who says she made her will in March 1589, proved May 1589. I knew this to be impossible, for I had seen a letter of hers among the Loseley Papers about poaching in the Park, dated 8th December 1589, with her clear beautiful signature shewing no sign of age or illness. Another letter there from Lord Howard backing up her application was dated the 9th of December 1589. I went to Somerset House and found her will (Somerset House, 21 Drury). To my surprise the probate was dated March i3th 1589, so that I saw it must have been by the old calendar. But on reading the will I found that it had been originally copied as having been drawn up on i5th April, 3oth Eliz., which would be 1588; but a tiny interpolation of "one and" made it 31 Eliz., that is, 1589. It had not been finally corrected, hence the errors. But, as it was quite evident that a will could not have been proved in March 1589 if it were written in April of that year, the officer in charge has now corrected it. So that March 1589 should read 1589-90.

Note 2. See Addenda.