Poems

Poems is in Books.

Books, Poems, John Taylor

TO SIR ROGER GRESLEY, BART.

TO SIR ROGER GRESLEY (age 21), Bart. On His Marriage With Lady SOPHIA COVENTRY, Youngest Daughter Of The EARL OF COVENTRY (age 63).

JUNE 2, 1821

IF mortals bliss can gain below,

Thou, GRESLEY, must the blessing know;

Nature at first to thee was kind,

She gave a shrewd and pregnant mind,

By taste and learning since refin'd.

Fortune, not less her pow'r to shew,

Has deign'd her favours to bestow;

Of riches an abundant store,

And, what thou now wilt value more,

To heighten ev'ry charm of life,

A nobler treasure in a wife,

Surpassing all in Plutus' pow'r,

Were e'en Peru his added dow'r;

A wife in manners, form, and mind,

The proudest would rejoice to find,

Possessing ev'ry gentler grace

That best adorns the female race.

Oh! still may Fortune prove thy friend,

And bliss on all thy course attend,

Till Nature, in a late decay,

Shall softly steal your lives away,

And angels then be hov'ring near

To waft ye to a happier sphere.

Books, Alexander Pope Poems

The Affairs of State

The Affairs of State Volume 3

1705. The Affairs of State Volume 3 was published.

The Affairs of State Volume 3 The Town Life

Once how I doated on this Jilting Town,

Thinking no Heaven was out of London known;

Till I her Beauties artificial found,

Her Pleasure's but a short and giddy round

Like one who has his Phillis long enjoy'd,

Grown with the fulsom Repetition cfoy'd

Love's Mists, then vanish from before his Eyes,

And all the Ladies Frailties he descries:

Quite surfeited with Joy, I now retreat

To the fresh Air, a homely Country Seat;

Good Hours, Books, harmless Sports, & wholsom Meat.

And now at last I Ve chose my proper Sphere,

Where Men are plain and rustick, but sincere.

I never was for Lies nor Fawning made,

But call a Wafer Bread, and Spade a Spade:

I tell what Merits got Lord [....] his Place,

And laugh at marry'd M[...]ve to his Face.

I cannot keep with every Change of State;

Nor flatter Villans, tho' at Court they're great:

Nor will I prostitute my Pen for Hire,

Praise Cromwell damn him, write the Spanish Fryar.

A Papist now, if next the Turk should reign,

Then piously transverse the Alcoran.

Methinks I hear one of the Nation cry,

Be-Crist, this is a Whiggish Calumny,

All Vertues are compriz'd in Loyalty,

Might I dispute with him, I'd change his Note,

I'd silence him, that is, he'd cut my Throat.

This powerful way of reasoning never mist,

None are so positive, but then desist

As I will, e'er it come to that extreme;

Our Eolly, not our Misery, is our Theme.

Well may we wonder what strange Charm, what Spell,

What mighty Pleasures in this London dwell,

That Men renounce their Ease, Estates and Fame,

And drudge it here to get a Fopling's Name.

That one of seeming Sense advanc'd in Years,

Like a Sir Courtly Nice in Town appears:

Others exchange their Land for tawdry Clothes

And will in spite of Nature pass for Beaus.

Indulgent Heaven, who ne'er made ought in Vain

Each Man for sommething proper did ordain

Yet most againft their Genius blindly run

The wrong they chuse,and what they're made for shun.

Thus Ar[...]n thinks for State-Affairs he's fit;

Hewit for Ogling, Chomly for Wit:

But 'tis vain, so wife, these Men to teach,

Besides the King's learn'd Priests should only preach.

We'll see how Sparks the tedious Day employ,

And trace them in their warm pursuit of Joy

If they get dreft (with much ado) by Noon,

In quiet of Beauty to the Mall they run,

Where (like, young Boys) with Hat in Hand they try

To catch some flutt'ring gawdy Butterfly.

Thus Gray pursues the Lady with a Face,

Like forty more, and with the same Success,

Whose Jilting Conduct in her Beauty's spite

Loses her Fame, and gets no Pleasure by't.

The secret Joys of an Intrigue she flights,

And in an Equipage of Fools delights:

So some vain Heroes for a vain Command,

Forfeit their Conscience, Liberty and Land.

But see high Mass is done, in Crowds they go?

What, all these Irish and Moll Howard too?

'Tis very late, to Lockets let's away,

The Lady Frances comes, I will not flay.

Expecting Dinner, to discourse they fall?

Without Respect of Morals, censuring all:

The Nymph they lov'd, the Friend they hug'd before

He's a vain Coxcomb, shes a common Whore:

No Obligation can their Jests prevent;

Wit, like unruly Wind in Bowels pent,

Torments the Bearer till he gives it vent

Tho' this offends the Ear, as that the Nose,

No matter, 'tis for Ease, and out it goes.

But what they talk ( too naufeous to rehearse )

I leave for the late Ballad-writers Verse.

After a dear-bought Meal, they haste away.

To a Desart of Ogling at the Play.

What's here which in the Box's Front I see!

Deform'd old Age, Diseases, Infamy!

Warwick, North, Paget, Hinton, Martin, Willis,

And that Eqitome of Lewdness, Ellys:

I'll not turn that way, but obferve the Play

Pox, 'tis a tragick Farce of Banks to Day:

Besides, some Irish Wits the Pit invade

With a worse Din than Cat-call Serenade.

I must be gone, let's to Hide-Park repair,

If not good Company, we'll find good Air.

Here with affected Bow and Side-Glass look,

The self-conceited Fool is eas'ly took.

There comes a Spark with fix inTarsels drest,

Charming the Ladies Hearts with dint of Beast

Like Scullers on the Themes with frequent Bow,

They labour, tug, and in their Coaches row;

To meet some fair one, still they wheel about, Till he retires, and then they hurry out.

But next we'll visit where the Beaus in order come,

(Tis yet too early for the drawing-room)

Here Nowels and Olivio's abound;

But one plain Manly is not to be found:

Flatt'ring the present, the absent they abuse,

And vent their Spleen and Lies, pretending News:

Why, such a Lady's pale and wou'd not Dance

This to the Country gone, and that to France

Who's marry'd, flipp'd away, or mist at Court;

Others Misfortunes thus afford them sport.

A new Song is produced, the Author guest,

The Verses and the Poet made a Jest.

Live Laureat E[...]er, in whom we see

The English can excel Antiquity.

Dryden writes Epick, Woosly Odes in vain

Virgil and Horace still the cheif maintain:

He with his mathless Poems has alone, Bavins and Mivius in their way out-done.

But new for Cards and Play they all propofe,

While I who never in good breeding lose

Who cannot civilly sit still and see

The Ladies pick the Purse, and laugh at me,

Pretending earnest Business, drive to Court,

Where those who can do nothing esle retort

The Fuglish must not seek Preferment there

For Mack's and O's all Places destin'd are

No more we'll fend our Youth to Paris now,

French Principles and Breeding one wou'd do

They for Improvement must to Ireland fail

The Irish Wit and Language now prevail.

But soft my Pen, with care this Subjeft touch

Stop where you are, you soon may write too much

Quite weary with the Hurry of the Day:

I to my peaceful Home direct my way;

While some in Hack, and Habit of Fatigue,

May have (but oft pretend) a close Intrigue

Others more open to the Tavern scow'r,

Calling for Wine, and every Man his Whore,

As safe as those with Quality perhaps,

For N[...]rgh says great Ladies can give Claps:

Some where they're kept, and many where they keep,

Most see an easy Mistrefs e'er they sleep,

Thus Sparks may dress, dance, play, write, fight, get drunk,

But all the mighty Pother ends in Punk.

Books, Byron Poems

Manfred

Between 1816 and 1817 George "Lord Byron" 6th Baron Byron (age 28) wrote the dramatic poem Manfred.

Manfred Scene II

The Mountain of the Jungfrau. Time, Morning. MANFRED alone upon the Cliffs.

MANFRED. The spirits I have raised abandon me,

The spells which I have studied baffled me,

The remedy I reck'd of tortured me;

I lean no more on super-human aid,

It hath no power upon the past, and for

The future, till the past be gulf'd in darkness,

It is not of my search. -- My mother Earth!

And thou fresh breaking Day, and you, ye Mountains,

Why are ye beautiful? I cannot love ye.

And thou, the bright eye of the universe

That openest over all, and unto all

Art a delight -- thou shin'st not on my heart.

And you, ye crags, upon whose extreme edge

I stand, and on the torrent's brink beneath

Behold the tall pines dwindled as to shrubs

In dizziness of distance; when a leap,

A stir, a motion, even a breath, would bring

My breast upon its rocky bosom's bed

To rest forever -- wherefore do I pause?

I feel the impulse--yet I do not plunge;

I see the peril -- yet do not recede;

And my brain reels -- and yet my foot is firm.

There is a power upon me which withholds,

And makes it my fatality to live;

If it be life to wear within myself

This barrenness of spirit, and to be

My own soul's sepulchre, for I have ceased

To justify my deeds unto myself --

The last infirmity of evil. Ay,

Thou winged and cloud-cleaving minister, [An eagle passes].

Whose happy flight is highest into heaven,

Well may'st thou swoop so near me -- I should be

Thy prey, and gorge thine eaglets; thou art gone

Where the eye cannot follow thee; but thine

Yet pierces downward, onward, or above,

With a pervading vision. -- Beautiful!

How beautiful is all this visible world!

How glorious in its action and itself!

But we, who name ourselves its sovereigns, we,

Half dust, half deity, alike unfit

To sink or soar, with our mix'd essence make

A conflict of its elements, and breathe

The breath of degradation and of pride,

Contending with low wants and lofty will,

Till our mortality predominates,

And men are what they name not to themselves,

And trust not to each other. Hark! the note,

[The Shepherd's pipe in the distance is heard.]

The natural music of the mountain reed

(For here the patriarchal days are not

A pastoral fable) pipes in the liberal air,

Mix'd with the sweet bells of the sauntering herd;

My soul would drink those echoes. -- Oh, that I were

The viewless spirit of a lovely sound,

A living voice, a breathing harmony,

A bodiless enjoyment -- born and dying

With the blessed tone which made me!

Enter from below a CHAMOIS HUNTER.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Even so

This way the chamois leapt: her nimble feet

Have baffled me; my gains to-day will scarce

Repay my break-neck travail. -- What is here?

Who seems not of my trade, and yet hath reach'd

A height which none even of our mountaineers

Save our best hunters, may attain: his garb

Is goodly, his mien manly, and his air

Proud as a freeborn peasant's, at this distance --

I will approach him nearer.

MANFRED (not perceiving the other). To be thus--

Gray--hair'd with anguish, like these blasted pines,

Wrecks of a single winter, barkless, branchless,

A blighted trunk upon a cursèd root

Which but supplies a feeling to decay --

And to be thus, eternally but thus,

Having been otherwise! Now furrowed o'er

With wrinkles, plough'd by moments, not by years

And hours -- all tortured into ages -- hours

Which I outlive! -- Ye toppling crags of ice!

Ye avalanches, whom a breath draws down

In mountainous o'erwhelming, come and crush me!

I hear ye momently above, beneath,

Crash with a frequent conflict, but ye pass,

And only fall on things that still would live;

On the young flourishing forest, or the hut

And hamlet of the harmless villager.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. The mists begin to rise from up the valley;

I'll warn him to descend, or he may chance

To lose at once his way and life together.

MANFRED. The mists boil up around the glaciers; clouds

Rise curling fast beneath me, white and sulphury,

Like foam from the roused ocean of deep Hell,

Whose every wave breaks on a living shore

Heap'd with the damn'd like pebbles.-- I am giddy.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. I must approach him cautiously; if near

A sudden step will startle him, and he

Seems tottering already.

MANFRED. Mountains have fallen,

Leaving a gap in the clouds, and with the shock

Rocking their Alpine brethren; filling up

The ripe green valleys with destruction's splinters;

Damming the rivers with a sudden dash,

Which crush'd the waters into mist, and made

Their fountains find another channel-- thus,

Thus, in its old age, did Mount Rosenberg--

Why stood I not beneath it?

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Friend! have a care,

Your next step may be fatal!-- for the love

Of him who made you, stand not on that brink!

MANFRED. (not hearing him). Such would have been for me a fitting tomb;

My bones had then been quiet in their depth;

They had not then been strewn upon the rocks

For the wind's pastime-- as thus-- thus they shall be--

In this one plunge.-- Farewell, ye opening heavens!

Look not upon me thus reproachfully--

Ye were not meant for me-- Earth! take these atoms!

[As MANFRED is in act to spring from the cliff, the CHAMOIS HUNTER seizes and retains him with a sudden grasp.]

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Hold, madman!-- though aweary of thy life,

Stain not our pure vales with thy guilty blood!

Away with me-- I will not quit my hold.

MANFRED. I am most sick at heart-- nay, grasp me not--

I am all feebleness-- the mountains whirl

Spinning around me-- I grow blind-- What art thou?

CHAMOIS HUNTER. I'll answer that anon.-- Away with me!

The clouds grow thicker-- there-- now lean on me--

Place your foot here-- here, take this staff, and cling

A moment to that shrub-- now give me your hand,

And hold fast by my girdle-- softly-- well--

The Chalet will be gain'd within an hour.

Come on, we'll quickly find a surer footing,

And something like a pathway, which the torrent

Hath wash'd since winter.-- Come, 'tis bravely done;

You should have been a hunter.-- Follow me.

[As they descend the rocks with difficulty, the scene closes.]

1840. Ford Madox Brown (age 18). "Manfred on the Jungfrau". Inspired by Scene II of the peom Manfred by George "Lord Byron" 6th Baron Byron.

1840. Ford Madox Brown (age 18). "Manfred on the Jungfrau". Inspired by Scene II of the peom Manfred by George "Lord Byron" 6th Baron Byron.

Books, Dante Poems

Sestina of the Lady Pietra degli Scrovigni

Sestina of the Lady Pietra degli Scrovigni is a poem by Dante Alighieri translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

To the dim light and the large circle of shade

I have clomb, and to the whitening of the hills,

There where we see no color in the grass.

Natheless my longing loses not its green,

It has so taken root in the hard stone

Which talks and hears as though it were a lady.

Utterly frozen is this youthful lady,

Even as the snow that lies within the shade;

For she is no more moved than is the stone

By the sweet season which makes warm the hills

And alters them afresh from white to green

Covering their sides again with flowers and grass.

When on her hair she sets a crown of grass

The thought has no more room for other lady,

Because she weaves the yellow with the green

So well that Love sits down there in the shade,-

Love who has shut me in among low hills

Faster than between walls of granite-stone.

She is more bright than is a precious stone;

The wound she gives may not be healed with grass:

I therefore have fled far o'er plains and hills

For refuge from so dangerous a lady;

But from her sunshine nothing can give shade,-

Not any hill, nor wall, nor summer-green.

A while ago, I saw her dressed in green,-

So fair, she might have wakened in a stone

This love which I do feel even for her shade;

And therefore, as one woos a graceful lady,

I wooed her in a field that was all grass

Girdled about with very lofty hills.

Yet shall the streams turn back and climb the hills

Before Love's flame in this damp wood and green

Burn, as it burns within a youthful lady,

For my sake, who would sleep away in stone

My life, or feed like beasts upon the grass,

Only to see her garments cast a shade.

How dark soe'er the hills throw out their shade,

Under her summer green the beautiful lady

Covers it, like a stone cover'd in grass.

Books, Swinburne Poems

Laus Veneris

In 1866 Algernon Charles Swinburne (age 28) wrote Laus Veneris, or The Praise of Venus:

Asleep or waking is it? for her neck,

Kissed over close, wears yet a purple speck

Wherein the pained blood falters and goes out;

Soft, and stung softly - fairer for a fleck.

But though my lips shut sucking on the place,

There is no vein at work upon her face;

Her eyelids are so peaceable, no doubt

Deep sleep has warmed her blood through all its ways.

Lo, this is she that was the world's delight;

The old grey years were parcels of her might;

The strewings of the ways wherein she trod

Were the twain seasons of the day and night.

Lo, she was thus when her clear limbs enticed

All lips that now grow sad with kissing Christ,

Stained with blood fallen from the feet of God,

The feet and hands whereat our souls were priced.

Alas, Lord, surely thou art great and fair.

But lo her wonderfully woven hair!

And thou didst heal us with thy piteous kiss;

But see now, Lord; her mouth is lovelier.

She is right fair; what hath she done to thee?

Nay, fair Lord Christ, lift up thine eyes and see;

Had now thy mother such a lip - like this?

Thou knowest how sweet a thing it is to me.

Inside the Horsel here the air is hot;

Right little peace one hath for it, God wot;

The scented dusty daylight burns the air,

And my heart chokes me till I hear it not.

Behold, my Venus, my soul's body, lies

With my love laid upon her garment-wise,

Feeling my love in all her limbs and hair

And shed between her eyelids through her eyes.

She holds my heart in her sweet open hands

Hanging asleep; hard by her head there stands,

Crowned with gilt thorns and clothed with flesh like fire,

Love, wan as foam blown up the salt burnt sands -

Hot as the brackish waifs of yellow spume

That shift and steam - loose clots of arid fume

From the sea's panting mouth of dry desire;

There stands he, like one labouring at a loom.

The warp holds fast across; and every thread

That makes the woof up has dry specks of red;

Always the shuttle cleaves clean through, and he

Weaves with the hair of many a ruined head.

Love is not glad nor sorry, as I deem;

Labouring he dreams, and labours in the dream,

Till when the spool is finished, lo I see

His web, reeled off, curls and goes out like steam.

Night falls like fire; the heavy lights run low,

And as they drop, my blood and body so

Shake as the flame shakes, full of days and hours

That sleep not neither weep they as they go.

Ah yet would God this flesh of mine might be

Where air might wash and long leaves cover me,

Where tides of grass break into foam of flowers,

Or where the wind's feet shine along the sea.

Ah yet would God that stems and roots were bred

Out of my weary body and my head,

That sleep were sealed upon me with a seal,

And I were as the least of all his dead.

Would God my blood were dew to feed the grass,

Mine ears made deaf and mine eyes blind as glass,

My body broken as a turning wheel,

And my mouth stricken ere it saith Alas!

Ah God, that love were as a flower or flame,

That life were as the naming of a name,

That death were not more pitiful than desire,

That these things were not one thing and the same!

Behold now, surely somewhere there is death:

For each man hath some space of years, he saith,

A little space of time ere time expire,

A little day, a little way of breath.

And lo, between the sundawn and the sun,

His day's work and his night's work are undone;

And lo, between the nightfall and the light,

He is not, and none knoweth of such an one.

Ah God, that I were as all souls that be,

As any herb or leaf of any tree,

As men that toil through hours of labouring night,

As bones of men under the deep sharp sea.

Outside it must be winter among men;

For at the gold bars of the gates again

I heard all night and all the hours of it

The wind's wet wings and fingers drip with rain.

Knights gather, riding sharp for cold; I know

The ways and woods are strangled with the snow;

And with short song the maidens spin and sit

Until Christ's birthnight, lily-like, arow.

The scent and shadow shed about me make

The very soul in all my senses ache;

The hot hard night is fed upon my breath,

And sleep beholds me from afar awake.

Alas, but surely where the hills grow deep,

Or where the wild ways of the sea are steep,

Or in strange places somewhere there is death,

And on death's face the scattered hair of sleep.

There lover-like with lips and limbs that meet

They lie, they pluck sweet fruit of life and eat;

But me the hot and hungry days devour,

And in my mouth no fruit of theirs is sweet.

No fruit of theirs, but fruit of my desire,

For her love's sake whose lips through mine respire;

Her eyelids on her eyes like flower on flower,

Mine eyelids on mine eyes like fire on fire.

So lie we, not as sleep that lies by death,

With heavy kisses and with happy breath;

Not as man lies by woman, when the bride

Laughs low for love's sake and the words he saith.

For she lies, laughing low with love; she lies

And turns his kisses on her lips to sighs,

To sighing sound of lips unsatisfied,

And the sweet tears are tender with her eyes.

Ah, not as they, but as the souls that were

Slain in the old time, having found her fair;

Who, sleeping with her lips upon their eyes,

Heard sudden serpents hiss across her hair.

Their blood runs round the roots of time like rain:

She casts them forth and gathers them again;

With nerve and bone she weaves and multiplies

Exceeding pleasure out of extreme pain.

Her little chambers drip with flower-like red,

Her girdles, and the chaplets of her head,

Her armlets and her anklets; with her feet

She tramples all that winepress of the dead.

Her gateways smoke with fume of flowers and fires,

With loves burnt out and unassuaged desires;

Between her lips the steam of them is sweet,

The languor in her ears of many lyres.

Her beds are full of perfume and sad sound,

Her doors are made with music, and barred round

With sighing and with laughter and with tears,

With tears whereby strong souls of men are bound.

There is the knight Adonis that was slain;

With flesh and blood she chains him for a chain;

The body and the spirit in her ears

Cry, for her lips divide him vein by vein.

Yea, all she slayeth; yea, every man save me;

Me, love, thy lover that must cleave to thee

Till the ending of the days and ways of earth,

The shaking of the sources of the sea.

Me, most forsaken of all souls that fell;

Me, satiated with things insatiable;

Me, for whose sake the extreme hell makes mirth,

Yea, laughter kindles at the heart of hell.

Alas thy beauty! for thy mouth's sweet sake

My soul is bitter to me, my limbs quake

As water, as the flesh of men that weep,

As their heart's vein whose heart goes nigh to break.

Ah God, that sleep with flower-sweet finger-tips

Would crush the fruit of death upon my lips;

Ah God, that death would tread the grapes of sleep

And wring their juice upon me as it drips.

There is no change of cheer for many days,

But change of chimes high up in the air, that sways

Rung by the running fingers of the wind;

And singing sorrows heard on hidden ways.

Day smiteth day in twain, night sundereth night,

And on mine eyes the dark sits as the light;

Yea, Lord, thou knowest I know not, having sinned,

If heaven be clean or unclean in thy sight.

Yea, as if earth were sprinkled over me,

Such chafed harsh earth as chokes a sandy sea,

Each pore doth yearn, and the dried blood thereof

Gasps by sick fits, my heart swims heavily,

There is a feverish famine in my veins;

Below her bosom, where a crushed grape stains

The white and blue, there my lips caught and clove

An hour since, and what mark of me remains?

I dare not always touch her, lest the kiss

Leave my lips charred. Yea, Lord, a little bliss,

Brief bitter bliss, one hath for a great sin;

Nathless thou knowest how sweet a thing it is.

Sin, is it sin whereby men's souls are thrust

Into the pit? yet had I a good trust

To save my soul before it slipped therein,

Trod under by the fire-shod feet of lust.

For if mine eyes fail and my soul takes breath,

I look between the iron sides of death

Into sad hell where all sweet love hath end,

All but the pain that never finisheth.

There are the naked faces of great kings,

The singing folk with all their lute-playings;

There when one cometh he shall have to friend

The grave that covets and the worm that clings.

There sit the knights that were so great of hand,

The ladies that were queens of fair green land,

Grown grey and black now, brought unto the dust,

Soiled, without raiment, clad about with sand.

There is one end for all of them; they sit

Naked and sad, they drink the dregs of it,

Trodden as grapes in the wine-press of lust,

Trampled and trodden by the fiery feet.

I see the marvellous mouth whereby there fell

Cities and people whom the gods loved well,

Yet for her sake on them the fire gat hold,

And for their sakes on her the fire of hell.

And softer than the Egyptian lote-leaf is,

The queen whose face was worth the world to kiss,

Wearing at breast a suckling snake of gold;

And large pale lips of strong Semiramis,

Curled like a tiger's that curl back to feed;

Red only where the last kiss made them bleed;

Her hair most thick with many a carven gem,

Deep in the mane, great-chested, like a steed.

Yea, with red sin the faces of them shine;

But in all these there was no sin like mine;

No, not in all the strange great sins of them

That made the wine-press froth and foam with wine.

For I was of Christ's choosing, I God's knight,

No blinkard heathen stumbling for scant light;

I can well see, for all the dusty days

Gone past, the clean great time of goodly fight.

I smell the breathing battle sharp with blows,

With shriek of shafts and snapping short of bows;

The fair pure sword smites out in subtle ways,

Sounds and long lights are shed between the rows

Of beautiful mailed men; the edged light slips,

Most like a snake that takes short breath and dips

Sharp from the beautifully bending head,

With all its gracious body lithe as lips

That curl in touching you; right in this wise

My sword doth, seeming fire in mine own eyes,

Leaving all colours in them brown and red

And flecked with death; then the keen breaths like sighs,

The caught-up choked dry laughters following them,

When all the fighting face is grown a flame

For pleasure, and the pulse that stuns the ears,

And the heart's gladness of the goodly game.

Let me think yet a little; I do know

These things were sweet, but sweet such years ago,

Their savour is all turned now into tears;

Yea, ten years since, where the blue ripples blow,

The blue curled eddies of the blowing Rhine,

I felt the sharp wind shaking grass and vine

Touch my blood too, and sting me with delight

Through all this waste and weary body of mine

That never feels clear air; right gladly then

I rode alone, a great way off my men,

And heard the chiming bridle smite and smite,

And gave each rhyme thereof some rhyme again,

Till my song shifted to that iron one;

Seeing there rode up between me and the sun

Some certain of my foe's men, for his three

White wolves across their painted coats did run.

The first red-bearded, with square cheeks - alack,

I made my knave's blood turn his beard to black;

The slaying of him was a joy to see:

Perchance too, when at night he came not back,

Some woman fell a-weeping, whom this thief

Would beat when he had drunken; yet small grief

Hath any for the ridding of such knaves;

Yea, if one wept, I doubt her teen was brief.

This bitter love is sorrow in all lands,

Draining of eyelids, wringing of drenched hands,

Sighing of hearts and filling up of graves;

A sign across the head of the world he stands,

An one that hath a plague-mark on his brows;

Dust and spilt blood do track him to his house

Down under earth; sweet smells of lip and cheek,

Like a sweet snake's breath made more poisonous

With chewing of some perfumed deadly grass,

Are shed all round his passage if he pass,

And their quenched savour leaves the whole soul weak,

Sick with keen guessing whence the perfume was.

As one who hidden in deep sedge and reeds

Smells the rare scent made where a panther feeds,

And tracking ever slotwise the warm smell

Is snapped upon by the sweet mouth and bleeds,

His head far down the hot sweet throat of her -

So one tracks love, whose breath is deadlier,

And lo, one springe and you are fast in hell,

Fast as the gin's grip of a wayfarer.

I think now, as the heavy hours decease

One after one, and bitter thoughts increase

One upon one, of all sweet finished things;

The breaking of the battle; the long peace

Wherein we sat clothed softly, each man's hair

Crowned with green leaves beneath white hoods of vair;

The sounds of sharp spears at great tourneyings,

And noise of singing in the late sweet air.

I sang of love too, knowing nought thereof;

"Sweeter," I said, "the little laugh of love

Than tears out of the eyes of Magdalen,

Or any fallen feather of the Dove.

"The broken little laugh that spoils a kiss,

The ache of purple pulses, and the bliss

Of blinded eyelids that expand again -

Love draws them open with those lips of his,

"Lips that cling hard till the kissed face has grown

Of one same fire and colour with their own;

Then ere one sleep, appeased with sacrifice,

Where his lips wounded, there his lips atone."

I sang these things long since and knew them not;

"Lo, here is love, or there is love, God wot,

This man and that finds favour in his eyes,"

I said, "but I, what guerdon have I got?

"The dust of praise that is blown everywhere

In all men's faces with the common air;

The bay-leaf that wants chafing to be sweet

Before they wind it in a singer's hair."

So that one dawn I rode forth sorrowing;

I had no hope but of some evil thing,

And so rode slowly past the windy wheat

And past the vineyard and the water-spring,

Up to the Horsel. A great elder-tree

Held back its heaps of flowers to let me see

The ripe tall grass, and one that walked therein,

Naked, with hair shed over to the knee.

She walked between the blossom and the grass;

I knew the beauty of her, what she was,

The beauty of her body and her sin,

And in my flesh the sin of hers, alas!

Alas! for sorrow is all the end of this.

O sad kissed mouth, how sorrowful it is!

O breast whereat some suckling sorrow clings,

Red with the bitter blossom of a kiss!

Ah, with blind lips I felt for you, and found

About my neck your hands and hair enwound,

The hands that stifle and the hair that stings,

I felt them fasten sharply without sound.

Yea, for my sin I had great store of bliss:

Rise up, make answer for me, let thy kiss

Seal my lips hard from speaking of my sin,

Lest one go mad to hear how sweet it is.

Yet I waxed faint with fume of barren bowers,

And murmuring of the heavy-headed hours;

And let the dove's beak fret and peck within

My lips in vain, and Love shed fruitless flowers.

So that God looked upon me when your hands

Were hot about me; yea, God brake my bands

To save my soul alive, and I came forth

Like a man blind and naked in strange lands

That hears men laugh and weep, and knows not whence

Nor wherefore, but is broken in his sense;

Howbeit I met folk riding from the north

Towards Rome, to purge them of their souls' offence,

And rode with them, and spake to none; the day

Stunned me like lights upon some wizard way,

And ate like fire mine eyes and mine eyesight;

So rode I, hearing all these chant and pray,

And marvelled; till before us rose and fell

White cursed hills, like outer skirts of hell

Seen where men's eyes look through the day to night,

Like a jagged shell's lips, harsh, untunable,

Blown in between by devils' wrangling breath;

Nathless we won well past that hell and death,

Down to the sweet land where all airs are good,

Even unto Rome where God's grace tarrieth.

Then came each man and worshipped at his knees

Who in the Lord God's likeness bears the keys

To bind or loose, and called on Christ's shed blood,

And so the sweet-souled father gave him ease.

But when I came I fell down at his feet,

Saying, "Father, though the Lord's blood be right sweet,

The spot it takes not off the panther's skin,

Nor shall an Ethiop's stain be bleached with it.

"Lo, I have sinned and have spat out at God,

Wherefore his hand is heavier and his rod

More sharp because of mine exceeding sin,

And all his raiment redder than bright blood

"Before mine eyes; yea, for my sake I wot

The heat of hell is waxen seven times hot

Through my great sin." Then spake he some sweet word,

Giving me cheer; which thing availed me not;

Yea, scarce I wist if such indeed were said;

For when I ceased - lo, as one newly dead

Who hears a great cry out of hell, I heard

The crying of his voice across my head.

"Until this dry shred staff, that hath no whit

Of leaf nor bark, bear blossom and smell sweet,

Seek thou not any mercy in God's sight,

For so long shalt thou be cast out from it."

Yea, what if dried-up stems wax red and green,

Shall that thing be which is not nor has been?

Yea, what if sapless bark wax green and white,

Shall any good fruit grow upon my sin?

Nay, though sweet fruit were plucked of a dry tree,

And though men drew sweet waters of the sea,

There should not grow sweet leaves on this dead stem,

This waste wan body and shaken soul of me.

Yea, though God search it warily enough,

There is not one sound thing in all thereof;

Though he search all my veins through, searching them

He shall find nothing whole therein but love.

For I came home right heavy, with small cheer,

And lo my love, mine own soul's heart, more dear

Than mine own soul, more beautiful than God,

Who hath my being between the hands of her -

Fair still, but fair for no man saving me,

As when she came out of the naked sea

Making the foam as fire whereon she trod,

And as the inner flower of fire was she.

Yea, she laid hold upon me, and her mouth

Clove unto mine as soul to body doth,

And, laughing, made her lips luxurious;

Her hair had smells of all the sunburnt south,

Strange spice and flower, strange savour of crushed fruit,

And perfume the swart kings tread underfoot

For pleasure when their minds wax amorous,

Charred frankincense and grated sandal-root.

And I forgot fear and all weary things,

All ended prayers and perished thanksgivings,

Feeling her face with all her eager hair

Cleave to me, clinging as a fire that clings

To the body and to the raiment, burning them;

As after death I know that such-like flame

Shall cleave to me for ever; yea, what care,

Albeit I burn then, having felt the same?

Ah love, there is no better life than this;

To have known love, how bitter a thing it is,

And afterward be cast out of God's sight;

Yea, these that know not, shall they have such bliss

High up in barren heaven before his face

As we twain in the heavy-hearted place,

Remembering love and all the dead delight,

And all that time was sweet with for a space?

For till the thunder in the trumpet be,

Soul may divide from body, but not we

One from another; I hold thee with my hand,

I let mine eyes have all their will of thee,

I seal myself upon thee with my might,

Abiding alway out of all men's sight

Until God loosen over sea and land

The thunder of the trumpets of the night.

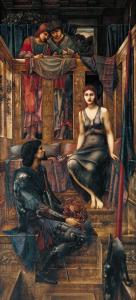

Between 1873 and 1878. Edward Coley Burne-Jones 1st Baronet (age 39). "Laus Veneris" or "The Praise of Venus". From the poem Laus Veneris by Algernon Charles Swinburne (age 35).

Between 1873 and 1878. Edward Coley Burne-Jones 1st Baronet (age 39). "Laus Veneris" or "The Praise of Venus". From the poem Laus Veneris by Algernon Charles Swinburne (age 35).

Books, Tennyson Poems

Mariana in the Moated Grange

In 1830 Alfred Tennyson 1st Baron Tennyson (age 20) published .

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look'd sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch;

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

Her tears fell with the dews at even;

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried;

She could not look on the sweet heaven,

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casement-curtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the night-fowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen's low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem'd to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "The day is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

About a stone-cast from the wall

A sluice with blacken'd waters slept,

And o'er it many, round and small,

The cluster'd marish-mosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silver-green with gnarled bark:

For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary

I would that I were dead!"

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up and away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak'd;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek'd,

Or from the crevice peer'd about.

Old faces glimmer'd thro' the doors

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

The sparrow's chirrup on the roof,

The slow clock ticking, and the sound

Which to the wooing wind aloof

The poplar made, did all confound

Her sense; but most she loathed the hour

When the thick-moted sunbeam lay

Athwart the chambers, and the day

Was sloping toward his western bower.

Then said she, "I am very dreary,

He will not come," she said;

She wept, "I am aweary, aweary,

Oh God, that I were dead!"

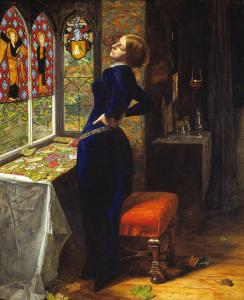

1850 to 1851. John Everett Millais 1st Baronet (age 20). "Mariana". The character in the Shakepeare play Measure for Measure and Tennyson's peom Mariana in the Moated Grange.

1850 to 1851. John Everett Millais 1st Baronet (age 20). "Mariana". The character in the Shakepeare play Measure for Measure and Tennyson's peom Mariana in the Moated Grange.

The Idylls of the King

Merlin and Vivien

A storm was coming, but the winds were still,

And in the wild woods of Broceliande,

Before an oak, so hollow, huge and old

It looked a tower of ivied masonwork,

At Merlin's feet the wily Vivien lay.

For he that always bare in bitter grudge

The slights of Arthur and his Table, Mark

The Cornish King, had heard a wandering voice,

A minstrel of Caerleon by strong storm

Blown into shelter at Tintagil, say

That out of naked knightlike purity

Sir Lancelot worshipt no unmarried girl

But the great Queen herself, fought in her name,

Sware by her-vows like theirs, that high in heaven

Love most, but neither marry, nor are given

In marriage, angels of our Lord's report.

He ceased, and then-for Vivien sweetly said

(She sat beside the banquet nearest Mark),

"And is the fair example followed, Sir,

In Arthur's household?"-answered innocently:

"Ay, by some few-ay, truly-youths that hold

It more beseems the perfect virgin knight

To worship woman as true wife beyond

All hopes of gaining, than as maiden girl.

They place their pride in Lancelot and the Queen.

So passionate for an utter purity

Beyond the limit of their bond, are these,

For Arthur bound them not to singleness.

Brave hearts and clean! and yet-God guide them-young."

Then Mark was half in heart to hurl his cup

Straight at the speaker, but forbore: he rose

To leave the hall, and, Vivien following him,

Turned to her. "Here are snakes within the grass;

And you methinks, O Vivien, save ye fear

The monkish manhood, and the mask of pure

Worn by this court, can stir them till they sting."

And Vivien answered, smiling scornfully,

"Why fear? because that fostered at thy court

I savour of thy-virtues? fear them? no.

As Love, if Love is perfect, casts out fear,

So Hate, if Hate is perfect, casts out fear.

My father died in battle against the King,

My mother on his corpse in open field;

She bore me there, for born from death was I

Among the dead and sown upon the wind-

And then on thee! and shown the truth betimes,

That old true filth, and bottom of the well

Where Truth is hidden. Gracious lessons thine

And maxims of the mud! 'This Arthur pure!

Great Nature through the flesh herself hath made

Gives him the lie! There is no being pure,

My cherub; saith not Holy Writ the same?'-

If I were Arthur, I would have thy blood.

Thy blessing, stainless King! I bring thee back,

When I have ferreted out their burrowings,

The hearts of all this Order in mine hand-

Ay-so that fate and craft and folly close,

Perchance, one curl of Arthur's golden beard.

To me this narrow grizzled fork of thine

Is cleaner-fashioned-Well, I loved thee first,

That warps the wit."

Loud laughed the graceless Mark,

But Vivien, into Camelot stealing, lodged

Low in the city, and on a festal day

When Guinevere- was crossing the great hall

Cast herself down, knelt to the Queen, and wailed.

"Why kneel ye there? What evil hath ye wrought?

Rise!" and the damsel bidden rise arose

And stood with folded hands and downward eyes

Of glancing corner, and all meekly said,

"None wrought, but suffered much, an orphan maid!

My father died in battle for thy King,

My mother on his corpse-in open field,

The sad sea-sounding wastes of Lyonnesse-

Poor wretch-no friend!-and now by Mark the King

For that small charm of feature mine, pursued-

If any such be mine-I fly to thee.

Save, save me thou-Woman of women-thine

The wreath of beauty, thine the crown of power,

Be thine the balm of pity, O Heaven's own white

Earth-angel, stainless bride of stainless King-

Help, for he follows! take me to thyself!

O yield me shelter for mine innocency

Among thy maidens!

Here her slow sweet eyes

Fear-tremulous, but humbly hopeful, rose

Fixt on her hearer's, while the Queen who stood

All glittering like May sunshine on May leaves

In green and gold, and plumed with green replied,

"Peace, child! of overpraise and overblame

We choose the last. Our noble Arthur, him

Ye scarce can overpraise, will hear and know.

Nay-we believe all evil of thy Mark-

Well, we shall test thee farther; but this hour

We ride a-hawking with Sir Lancelot.

He hath given us a fair falcon which he trained;

We go to prove it. Bide ye here the while."

She past; and Vivien murmured after "Go!

I bide the while." Then through the portal-arch

Peering askance, and muttering broken-wise,

As one that labours with an evil dream,

Beheld the Queen and Lancelot get to horse.

"Is that the Lancelot? goodly-ay, but gaunt:

Courteous-amends for gauntness-takes her hand-

That glance of theirs, but for the street, had been

A clinging kiss-how hand lingers in hand!

Let go at last!-they ride away-to hawk

For waterfowl. Royaller game is mine.

For such a supersensual sensual bond

As that gray cricket chirpt of at our hearth-

Touch flax with flame-a glance will serve-the liars!

Ah little rat that borest in the dyke

Thy hole by night to let the boundless deep

Down upon far-off cities while they dance-

Or dream-of thee they dreamed not-nor of me

These-ay, but each of either: ride, and dream

The mortal dream that never yet was mine-

Ride, ride and dream until ye wake-to me!

Then, narrow court and lubber King, farewell!

For Lancelot will be gracious to the rat,

And our wise Queen, if knowing that I know,

Will hate, loathe, fear-but honour me the more."

Yet while they rode together down the plain,

Their talk was all of training, terms of art,

Diet and seeling, jesses, leash and lure.

"She is too noble" he said "to check at pies,

Nor will she rake: there is no baseness in her."

Here when the Queen demanded as by chance

"Know ye the stranger woman?. "Let her be,"

Said Lancelot and unhooded casting off

The goodly falcon free; she towered; her bells,

Tone under tone, shrilled; and they lifted up

Their eager faces, wondering at the strength,

Boldness and royal knighthood of the bird

Who pounced her quarry and slew it. Many a time

As once-of old-among the flowers-they rode.

But Vivien half-forgotten of the Queen

Among her damsels broidering sat, heard, watched

And whispered: through the peaceful court she crept

And whispered: then as Arthur in the highest

Leavened the world, so Vivien in the lowest,

Arriving at a time of golden rest,

And sowing one ill hint from ear to ear,

While all the heathen lay at Arthur's feet,

And no quest came, but all was joust and play,

Leavened his hall. They heard and let her be.

Thereafter as an enemy that has left

Death in the living waters, and withdrawn,

The wily Vivien stole from Arthur's court.

She hated all the knights, and heard in thought

Their lavish comment when her name was named.

For once, when Arthur walking all alone,

Vext at a rumour issued from herself

Of some corruption crept among his knights,

Had met her, Vivien, being greeted fair,

Would fain have wrought upon his cloudy mood

With reverent eyes mock-loyal, shaken voice,

And fluttered adoration, and at last

With dark sweet hints of some who prized him more

Than who should prize him most; at which the King

Had gazed upon her blankly and gone by:

But one had watched, and had not held his peace:

It made the laughter of an afternoon

That Vivien should attempt the blameless King.

And after that, she set herself to gain

Him, the most famous man of all those times,

Merlin, who knew the range of all their arts,

Had built the King his havens, ships, and halls,

Was also Bard, and knew the starry heavens;

The people called him Wizard; whom at first

She played about with slight and sprightly talk,

And vivid smiles, and faintly-venomed points

Of slander, glancing here and grazing there;

And yielding to his kindlier moods, the Seer

Would watch her at her petulance, and play,

Even when they seemed unloveable, and laugh

As those that watch a kitten; thus he grew

Tolerant of what he half disdained, and she,

Perceiving that she was but half disdained,

Began to break her sports with graver fits,

Turn red or pale, would often when they met

Sigh fully, or all-silent gaze upon him

With such a fixt devotion, that the old man,

Though doubtful, felt the flattery, and at times

Would flatter his own wish in age for love,

And half believe her true: for thus at times

He wavered; but that other clung to him,

Fixt in her will, and so the seasons went.

Then fell on Merlin a great melancholy;

He walked with dreams and darkness, and he found

A doom that ever poised itself to fall,

An ever-moaning battle in the mist,

World-war of dying flesh against the life,

Death in all life and lying in all love,

The meanest having power upon the highest,

And the high purpose broken by the worm.

So leaving Arthur's court he gained the beach;

There found a little boat, and stept into it;

And Vivien followed, but he marked her not.

She took the helm and he the sail; the boat

Drave with a sudden wind across the deeps,

And touching Breton sands, they disembarked.

And then she followed Merlin all the way,

Even to the wild woods of Broceliande.

For Merlin once had told her of a charm,

The which if any wrought on anyone

With woven paces and with waving arms,

The man so wrought on ever seemed to lie

Closed in the four walls of a hollow tower,

From which was no escape for evermore;

And none could find that man for evermore,

Nor could he see but him who wrought the charm

Coming and going, and he lay as dead

And lost to life and use and name and fame.

And Vivien ever sought to work the charm

Upon the great Enchanter of the Time,

As fancying that her glory would be great

According to his greatness whom she quenched.

There lay she all her length and kissed his feet,

As if in deepest reverence and in love.

A twist of gold was round her hair; a robe

Of samite without price, that more exprest

Than hid her, clung about her lissome limbs,

In colour like the satin-shining palm

On sallows in the windy gleams of March:

And while she kissed them, crying, "Trample me,

Dear feet, that I have followed through the world,

And I will pay you worship; tread me down

And I will kiss you for it;" he was mute:

So dark a forethought rolled about his brain,

As on a dull day in an Ocean cave

The blind wave feeling round his long sea-hall

In silence: wherefore, when she lifted up

A face of sad appeal, and spake and said,

"O Merlin, do ye love me?" and again,

"O Merlin, do ye love me?" and once more,

"Great Master, do ye love me?" he was mute.

And lissome Vivien, holding by his heel,

Writhed toward him, slided up his knee and sat,

Behind his ankle twined her hollow feet

Together, curved an arm about his neck,

Clung like a snake; and letting her left hand

Droop from his mighty shoulder, as a leaf,

Made with her right a comb of pearl to part

The lists of such a board as youth gone out

Had left in ashes: then he spoke and said,

Not looking at her, "Who are wise in love

Love most, say least," and Vivien answered quick,

"I saw the little elf-god eyeless once

In Arthur's arras hall at Camelot:

But neither eyes nor tongue-O stupid child!

Yet you are wise who say it; let me think

Silence is wisdom: I am silent then,

And ask no kiss;" then adding all at once,

"And lo, I clothe myself with wisdom," drew

The vast and shaggy mantle of his beard

Across her neck and bosom to her knee,

And called herself a gilded summer fly

Caught in a great old tyrant spider's web,

Who meant to eat her up in that wild wood

Without one word. So Vivien called herself,

But rather seemed a lovely baleful star

Veiled in gray vapour; till he sadly smiled:

"To what request for what strange boon," he said,

"Are these your pretty tricks and fooleries,

O Vivien, the preamble? yet my thanks,

For these have broken up my melancholy."

And Vivien answered smiling saucily,

"What, O my Master, have ye found your voice?

I bid the stranger welcome. Thanks at last!

But yesterday you never opened lip,

Except indeed to drink: no cup had we:

In mine own lady palms I culled the spring

That gathered trickling dropwise from the cleft,

And made a pretty cup of both my hands

And offered you it kneeling: then you drank

And knew no more, nor gave me one poor word;

O no more thanks than might a goat have given

With no more sign of reverence than a beard.

And when we halted at that other well,

And I was faint to swooning, and you lay

Foot-gilt with all the blossom-dust of those

Deep meadows we had traversed, did you know

That Vivien bathed your feet before her own?

And yet no thanks: and all through this wild wood

And all this morning when I fondled you:

Boon, ay, there was a boon, one not so strange-

How had I wronged you? surely ye are wise,

But such a silence is more wise than kind."

And Merlin locked his hand in hers and said:

"O did ye never lie upon the shore,

And watch the curled white of the coming wave

Glassed in the slippery sand before it breaks?

Even such a wave, but not so pleasurable,

Dark in the glass of some presageful mood,

Had I for three days seen, ready to fall.

And then I rose and fled from Arthur's court

To break the mood. You followed me unasked;

And when I looked, and saw you following me still,

My mind involved yourself the nearest thing

In that mind-mist: for shall I tell you truth?

You seemed that wave about to break upon me

And sweep me from my hold upon the world,

My use and name and fame. Your pardon, child.

Your pretty sports have brightened all again.

And ask your boon, for boon I owe you thrice,

Once for wrong done you by confusion, next

For thanks it seems till now neglected, last

For these your dainty gambols: wherefore ask;

And take this boon so strange and not so strange."

And Vivien answered smiling mournfully:

"O not so strange as my long asking it,

Not yet so strange as you yourself are strange,

Nor half so strange as that dark mood of yours.

I ever feared ye were not wholly mine;

And see, yourself have owned ye did me wrong.

The people call you prophet: let it be:

But not of those that can expound themselves.

Take Vivien for expounder; she will call

That three-days-long presageful gloom of yours

No presage, but the same mistrustful mood

That makes you seem less noble than yourself,

Whenever I have asked this very boon,

Now asked again: for see you not, dear love,

That such a mood as that, which lately gloomed

Your fancy when ye saw me following you,

Must make me fear still more you are not mine,

Must make me yearn still more to prove you mine,

And make me wish still more to learn this charm

Of woven paces and of waving hands,

As proof of trust. O Merlin, teach it me.

The charm so taught will charm us both to rest.

For, grant me some slight power upon your fate,

I, feeling that you felt me worthy trust,

Should rest and let you rest, knowing you mine.

And therefore be as great as ye are named,

Not muffled round with selfish reticence.

How hard you look and how denyingly!

O, if you think this wickedness in me,

That I should prove it on you unawares,

That makes me passing wrathful; then our bond

Had best be loosed for ever: but think or not,

By Heaven that hears I tell you the clean truth,

As clean as blood of babes, as white as milk:

O Merlin, may this earth, if ever I,

If these unwitty wandering wits of mine,

Even in the jumbled rubbish of a dream,

Have tript on such conjectural treachery-

May this hard earth cleave to the Nadir hell

Down, down, and close again, and nip me flat,

If I be such a traitress. Yield my boon,

Till which I scarce can yield you all I am;

And grant my re-reiterated wish,

The great proof of your love: because I think,

However wise, ye hardly know me yet."

And Merlin loosed his hand from hers and said,

"I never was less wise, however wise,

Too curious Vivien, though you talk of trust,

Than when I told you first of such a charm.

Yea, if ye talk of trust I tell you this,

Too much I trusted when I told you that,

And stirred this vice in you which ruined man

Through woman the first hour; for howsoe'er

In children a great curiousness be well,

Who have to learn themselves and all the world,

In you, that are no child, for still I find

Your face is practised when I spell the lines,

I call it,-well, I will not call it vice:

But since you name yourself the summer fly,

I well could wish a cobweb for the gnat,

That settles, beaten back, and beaten back

Settles, till one could yield for weariness:

But since I will not yield to give you power

Upon my life and use and name and fame,

Why will ye never ask some other boon?

Yea, by God's rood, I trusted you too much."

And Vivien, like the tenderest-hearted maid

That ever bided tryst at village stile,

Made answer, either eyelid wet with tears:

"Nay, Master, be not wrathful with your maid;

Caress her: let her feel herself forgiven

Who feels no heart to ask another boon.

I think ye hardly know the tender rhyme

Of 'trust me not at all or all in all.'

I heard the great Sir Lancelot sing it once,

And it shall answer for me. Listen to it.

'In Love, if Love be Love, if Love be ours,

Faith and unfaith can ne'er be equal powers:

Unfaith in aught is want of faith in all.

'It is the little rift within the lute,

That by and by will make the music mute,

And ever widening slowly silence all.

'The little rift within the lover's lute

Or little pitted speck in garnered fruit,

That rotting inward slowly moulders all.

'It is not worth the keeping: let it go:

But shall it? answer, darling, answer, no.

And trust me not at all or all in all.'

O Master, do ye love my tender rhyme?"

And Merlin looked and half believed her true,

So tender was her voice, so fair her face,

So sweetly gleamed her eyes behind her tears

Like sunlight on the plain behind a shower:

And yet he answered half indignantly:

"Far other was the song that once I heard

By this huge oak, sung nearly where we sit:

For here we met, some ten or twelve of us,

To chase a creature that was current then

In these wild woods, the hart with golden horns.

It was the time when first the question rose

About the founding of a Table Round,

That was to be, for love of God and men

And noble deeds, the flower of all the world.

And each incited each to noble deeds.

And while we waited, one, the youngest of us,

We could not keep him silent, out he flashed,

And into such a song, such fire for fame,

Such trumpet-glowings in it, coming down

To such a stern and iron-clashing close,

That when he stopt we longed to hurl together,

And should have done it; but the beauteous beast

Scared by the noise upstarted at our feet,

And like a silver shadow slipt away

Through the dim land; and all day long we rode

Through the dim land against a rushing wind,

That glorious roundel echoing in our ears,

And chased the flashes of his golden horns

Till they vanished by the fairy well

That laughs at iron-as our warriors did-

Where children cast their pins and nails, and cry,

'Laugh, little well!' but touch it with a sword,

It buzzes fiercely round the point; and there

We lost him: such a noble song was that.

But, Vivien, when you sang me that sweet rhyme,

I felt as though you knew this cursed charm,

Were proving it on me, and that I lay

And felt them slowly ebbing, name and fame."

And Vivien answered smiling mournfully:

"O mine have ebbed away for evermore,

And all through following you to this wild wood,

Because I saw you sad, to comfort you.

Lo now, what hearts have men! they never mount

As high as woman in her selfless mood.

And touching fame, howe'er ye scorn my song,

Take one verse more-the lady speaks it-this:

"'My name, once mine, now thine, is closelier mine,

For fame, could fame be mine, that fame were thine,

And shame, could shame be thine, that shame were mine.

So trust me not at all or all in all.'

"Says she not well? and there is more-this rhyme

Is like the fair pearl-necklace of the Queen,

That burst in dancing, and the pearls were spilt;

Some lost, some stolen, some as relics kept.

But nevermore the same two sister pearls

Ran down the silken thread to kiss each other

On her white neck-so is it with this rhyme:

It lives dispersedly in many hands,

And every minstrel sings it differently;

Yet is there one true line, the pearl of pearls:

'Man dreams of Fame while woman wakes to love.'

Yea! Love, though Love were of the grossest, carves

A portion from the solid present, eats

And uses, careless of the rest; but Fame,

The Fame that follows death is nothing to us;

And what is Fame in life but half-disfame,

And counterchanged with darkness? ye yourself

Know well that Envy calls you Devil's son,

And since ye seem the Master of all Art,

They fain would make you Master of all vice."

And Merlin locked his hand in hers and said,

"I once was looking for a magic weed,

And found a fair young squire who sat alone,

Had carved himself a knightly shield of wood,

And then was painting on it fancied arms,

Azure, an Eagle rising or, the Sun

In dexter chief; the scroll 'I follow fame.'

And speaking not, but leaning over him

I took his brush and blotted out the bird,

And made a Gardener putting in a graff,

With this for motto, 'Rather use than fame.'

You should have seen him blush; but afterwards

He made a stalwart knight. O Vivien,

For you, methinks you think you love me well;

For me, I love you somewhat; rest: and Love

Should have some rest and pleasure in himself,

Not ever be too curious for a boon,

Too prurient for a proof against the grain

Of him ye say ye love: but Fame with men,

Being but ampler means to serve mankind,

Should have small rest or pleasure in herself,

But work as vassal to the larger love,

That dwarfs the petty love of one to one.

Use gave me Fame at first, and Fame again

Increasing gave me use. Lo, there my boon!

What other? for men sought to prove me vile,

Because I fain had given them greater wits:

And then did Envy call me Devil's son:

The sick weak beast seeking to help herself

By striking at her better, missed, and brought

Her own claw back, and wounded her own heart.

Sweet were the days when I was all unknown,

But when my name was lifted up, the storm

Brake on the mountain and I cared not for it.

Right well know I that Fame is half-disfame,

Yet needs must work my work. That other fame,

To one at least, who hath not children, vague,

The cackle of the unborn about the grave,

I cared not for it: a single misty star,

Which is the second in a line of stars

That seem a sword beneath a belt of three,

I never gazed upon it but I dreamt

Of some vast charm concluded in that star

To make fame nothing. Wherefore, if I fear,

Giving you power upon me through this charm,

That you might play me falsely, having power,

However well ye think ye love me now

(As sons of kings loving in pupilage

Have turned to tyrants when they came to power)

I rather dread the loss of use than fame;

If you-and not so much from wickedness,

As some wild turn of anger, or a mood

Of overstrained affection, it may be,

To keep me all to your own self,-or else

A sudden spurt of woman's jealousy,-

Should try this charm on whom ye say ye love."

And Vivien answered smiling as in wrath:

"Have I not sworn? I am not trusted. Good!

Well, hide it, hide it; I shall find it out;

And being found take heed of Vivien.

A woman and not trusted, doubtless I

Might feel some sudden turn of anger born

Of your misfaith; and your fine epithet

Is accurate too, for this full love of mine

Without the full heart back may merit well

Your term of overstrained. So used as I,

My daily wonder is, I love at all.

And as to woman's jealousy, O why not?

O to what end, except a jealous one,

And one to make me jealous if I love,

Was this fair charm invented by yourself?

I well believe that all about this world

Ye cage a buxom captive here and there,

Closed in the four walls of a hollow tower

From which is no escape for evermore."

Then the great Master merrily answered her:

"Full many a love in loving youth was mine;

I needed then no charm to keep them mine

But youth and love; and that full heart of yours

Whereof ye prattle, may now assure you mine;

So live uncharmed. For those who wrought it first,

The wrist is parted from the hand that waved,

The feet unmortised from their ankle-bones

Who paced it, ages back: but will ye hear

The legend as in guerdon for your rhyme?

"There lived a king in the most Eastern East,

Less old than I, yet older, for my blood

Hath earnest in it of far springs to be.

A tawny pirate anchored in his port,

Whose bark had plundered twenty nameless isles;

And passing one, at the high peep of dawn,

He saw two cities in a thousand boats

All fighting for a woman on the sea.

And pushing his black craft among them all,

He lightly scattered theirs and brought her off,

With loss of half his people arrow-slain;

A maid so smooth, so white, so wonderful,

They said a light came from her when she moved:

And since the pirate would not yield her up,

The King impaled him for his piracy;

Then made her Queen: but those isle-nurtured eyes

Waged such unwilling though successful war

On all the youth, they sickened; councils thinned,

And armies waned, for magnet-like she drew

The rustiest iron of old fighters' hearts;

And beasts themselves would worship; camels knelt

Unbidden, and the brutes of mountain back

That carry kings in castles, bowed black knees

Of homage, ringing with their serpent hands,

To make her smile, her golden ankle-bells.

What wonder, being jealous, that he sent

His horns of proclamation out through all

The hundred under-kingdoms that he swayed

To find a wizard who might teach the King

Some charm, which being wrought upon the Queen

Might keep her all his own: to such a one

He promised more than ever king has given,

A league of mountain full of golden mines,

A province with a hundred miles of coast,

A palace and a princess, all for him:

But on all those who tried and failed, the King

Pronounced a dismal sentence, meaning by it

To keep the list low and pretenders back,

Or like a king, not to be trifled with-

Their heads should moulder on the city gates.

And many tried and failed, because the charm

Of nature in her overbore their own:

And many a wizard brow bleached on the walls:

And many weeks a troop of carrion crows

Hung like a cloud above the gateway towers."

And Vivien breaking in upon him, said:

"I sit and gather honey; yet, methinks,

Thy tongue has tript a little: ask thyself.

The lady never made unwilling war

With those fine eyes: she had her pleasure in it,

And made her good man jealous with good cause.

And lived there neither dame nor damsel then

Wroth at a lover's loss? were all as tame,

I mean, as noble, as the Queen was fair?

Not one to flirt a venom at her eyes,

Or pinch a murderous dust into her drink,

Or make her paler with a poisoned rose?

Well, those were not our days: but did they find

A wizard? Tell me, was he like to thee?

She ceased, and made her lithe arm round his neck

Tighten, and then drew back, and let her eyes

Speak for her, glowing on him, like a bride's

On her new lord, her own, the first of men.

He answered laughing, "Nay, not like to me.

At last they found-his foragers for charms-

A little glassy-headed hairless man,

Who lived alone in a great wild on grass;

Read but one book, and ever reading grew

So grated down and filed away with thought,

So lean his eyes were monstrous; while the skin

Clung but to crate and basket, ribs and spine.

And since he kept his mind on one sole aim,

Nor ever touched fierce wine, nor tasted flesh,

Nor owned a sensual wish, to him the wall

That sunders ghosts and shadow-casting men

Became a crystal, and he saw them through it,

And heard their voices talk behind the wall,

And learnt their elemental secrets, powers

And forces; often o'er the sun's bright eye

Drew the vast eyelid of an inky cloud,

And lashed it at the base with slanting storm;

Or in the noon of mist and driving rain,

When the lake whitened and the pinewood roared,

And the cairned mountain was a shadow, sunned

The world to peace again: here was the man.

And so by force they dragged him to the King.

And then he taught the King to charm the Queen

In such-wise, that no man could see her more,

Nor saw she save the King, who wrought the charm,

Coming and going, and she lay as dead,

And lost all use of life: but when the King

Made proffer of the league of golden mines,

The province with a hundred miles of coast,

The palace and the princess, that old man

Went back to his old wild, and lived on grass,

And vanished, and his book came down to me."

And Vivien answered smiling saucily:

"Ye have the book: the charm is written in it:

Good: take my counsel: let me know it at once:

For keep it like a puzzle chest in chest,

With each chest locked and padlocked thirty-fold,

And whelm all this beneath as vast a mound

As after furious battle turfs the slain

On some wild down above the windy deep,

I yet should strike upon a sudden means

To dig, pick, open, find and read the charm:

Then, if I tried it, who should blame me then?"

And smiling as a master smiles at one

That is not of his school, nor any school

But that where blind and naked Ignorance

Delivers brawling judgments, unashamed,

On all things all day long, he answered her:

"Thou read the book, my pretty Vivien!

O ay, it is but twenty pages long,

But every page having an ample marge,

And every marge enclosing in the midst

A square of text that looks a little blot,

The text no larger than the limbs of fleas;

And every square of text an awful charm,

Writ in a language that has long gone by.

So long, that mountains have arisen since

With cities on their flanks-thou read the book!

And ever margin scribbled, crost, and crammed

With comment, densest condensation, hard

To mind and eye; but the long sleepless nights

Of my long life have made it easy to me.

And none can read the text, not even I;

And none can read the comment but myself;

And in the comment did I find the charm.

O, the results are simple; a mere child

Might use it to the harm of anyone,

And never could undo it: ask no more:

For though you should not prove it upon me,

But keep that oath ye sware, ye might, perchance,

Assay it on some one of the Table Round,

And all because ye dream they babble of you."

And Vivien, frowning in true anger, said:

"What dare the full-fed liars say of me?

They ride abroad redressing human wrongs!

They sit with knife in meat and wine in horn!

They bound to holy vows of chastity!

Were I not woman, I could tell a tale.

But you are man, you well can understand

The shame that cannot be explained for shame.

Not one of all the drove should touch me: swine!"

Then answered Merlin careless of her words:

"You breathe but accusation vast and vague,

Spleen-born, I think, and proofless. If ye know,

Set up the charge ye know, to stand or fall!"

And Vivien answered frowning wrathfully:

"O ay, what say ye to Sir Valence, him

Whose kinsman left him watcher o'er his wife

And two fair babes, and went to distant lands;

Was one year gone, and on returning found

Not two but three? there lay the reckling, one

But one hour old! What said the happy sire?"

A seven-months' babe had been a truer gift.

Those twelve sweet moons confused his fatherhood."

Then answered Merlin, "Nay, I know the tale.

Sir Valence wedded with an outland dame:

Some cause had kept him sundered from his wife:

One child they had: it lived with her: she died:

His kinsman travelling on his own affair

Was charged by Valence to bring home the child.

He brought, not found it therefore: take the truth."

"O ay," said Vivien, "overtrue a tale.

What say ye then to sweet Sir Sagramore,

That ardent man? 'to pluck the flower in season,'

So says the song, 'I trow it is no treason.'

O Master, shall we call him overquick

To crop his own sweet rose before the hour?"

And Merlin answered, "Overquick art thou

To catch a loathly plume fallen from the wing

Of that foul bird of rapine whose whole prey

Is man's good name: he never wronged his bride.