Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter IV

Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter IV is in Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries.

Derbyshire

The next group of monuments with which we have to deal is perhaps as interesting as any of those hitherto described. As before mentioned, when speaking of the labours of William and Thomas Bateman, the north-western portion of the county is crowded with barrows, but none apparently of so ancient a character as those excavated by Canon Greenwell (age 51) in Yorkshire, and most of them containing objects of so miscellaneous a character as to defy systematic classification. As these, however, hardly belong to the subject of which we are now treating, it is not necessary to say more about them at present; and the less so, that the group which falls directly in with our line of research is well defined as to locality, and probably also as to age.

The principal monument of this group is well-known to antiquaries as Arbe or Arbor Low [Map], and is situated about nine miles south by east from Buxton, and by a curious coincidence is placed in the same relative position to the Roman Road as Avebury. So much is this the case, that in the Ordnance Survey—barring the scale—the one might be mistaken for the other if cut out from the neighbouring objects. Minning Low [Map], however, which is the pendant of Silbury Hill in this group, is four miles off, though still in the line of the Roman road, instead of only one mile, as in the Wiltshire example. Besides, there is a most interesting Saxon Low at Benty Grange, about one mile from Arbor Low. Gib Hill, Kens Low, Ringham Low, End Low, Lean Low, and probably altogether ten or twelve important mounds covering a space five miles in one direction, by one and a half to two miles across.

Note 165. First described in the 'Archæologia,' vol. viii. p. 131 et seq., by the Rev. S. Pegge, in 1783.

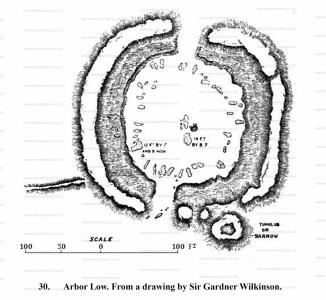

Arbor Low consists of a circular platform, 167 feet in diameter, surrounded by a ditch 18 feet broad at bottom, the earth taken from which has been used to form a rampart about 15 feet to 18 feet high, and measuring about 820 feet in circumference on the top. The first thing that strikes us on looking at the plan (woodcut No. 30) is that, in design and general dimensions, the monument is identical with that called "Arthur's Round Table," at Penrith. The one difference is that, in this instance, the section of the ditch, and consequently that of the rampart, have been increased at the expense of the berm; but the arrangements of both are the same, and so are the internal and external dimensions. At Arbor Low there are two entrances across the ditch, as there was in the Cumberland and Dumfriesshire examples. As mentioned above, only one is now visible there, the other having been obliterated by the road, but the two circles are in other respects so similar as to leave very little doubt as to their true features.

The Derbyshire example, however, possesses, in addition to its earthworks, a circle of stones on its inner platform, originally probably forty or fifty in number; but all now prostrate, except perhaps some of the smallest, which, being nearly cubical, may still be in situ. In the centre of the platform, also, are several very large stones, which evidently formed part of a central dolmen.

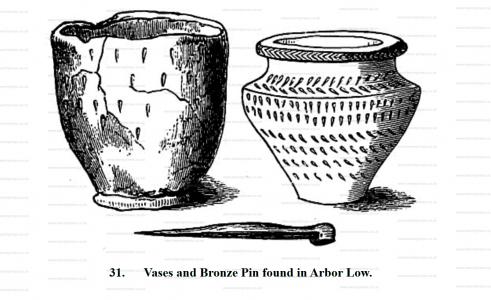

There is another very interesting addition at Arbor Low, which is wanting at Penrith, this is a tumulus [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] attached unsymmetrically to the outer vallum. This was, after repeated attempts, at last successfully excavated by the Messrs. Bateman, and found to contain a cist of rather irregular shape, in which were found among other things two vases167 one of singularly elegant shape, the other less so. In themselves these objects are not sufficient to determine the age of the barrow, but they suffice to show that it was not very early. One great point of interest in this discovery is its position with reference to the circle. It is identical with that of Long Meg with reference to her daughters, and perhaps some of the stones outside Avebury, supposed to be the commencement of the avenue, may mark the principal places of interment.

Note 167. Bateman, 'Vestiges,' p. 65.

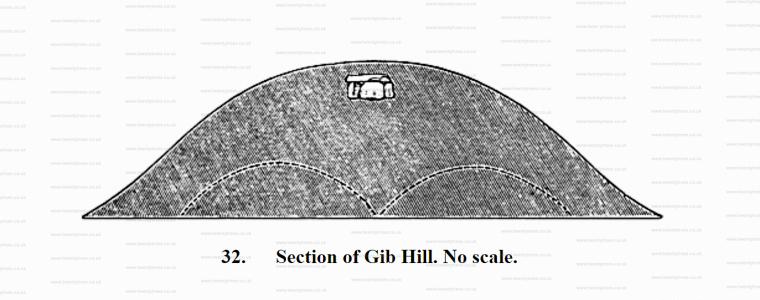

Attached to Arbor Low, at a distance of about 250 yards, is another tumulus, called Gib Hill [Map], apparently about 70 to 80 feet in diameter168. It was carefully excavated by Mr. T. Bateman in 1848; but after tunnelling through and through it in every direction on the ground level and finding nothing, he was surprised at finding, on removing the timber which supported his galleries, that the side of the hill fell in, and disclosed the cist very near the summit. The whole fell down, and the stones composing the cist were removed and re-erected in the garden of Lumberdale House. It consisted of four massive blocks of limestone forming the sides of a chamber, 2 feet by 2 feet 6 inches, and covered by one 4 feet square. The cap stone was not more than 18 inches below the turf. By the sudden fall of the side a very pretty vase was crushed, the fragments mingling with the burnt bones it contained; but though restored, unfortunately no representation has been given. The only other articles found in this tumulus were "a battered celt of basaltic stone, a dart or javelin-point of flint, and a small iron fibula, which had been enriched with precious stones."

Note 168. These dimensions are taken from Sir Gardner Wilkinson's plan. The Batemans, with all their merits, are singularly careless in quoting dimensions.

Note 169. Ante, p. 11.

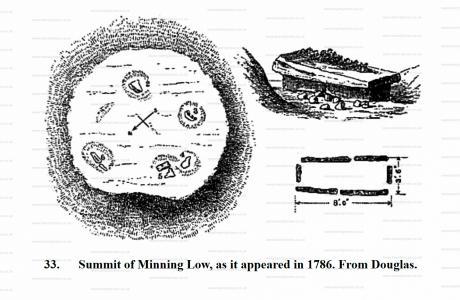

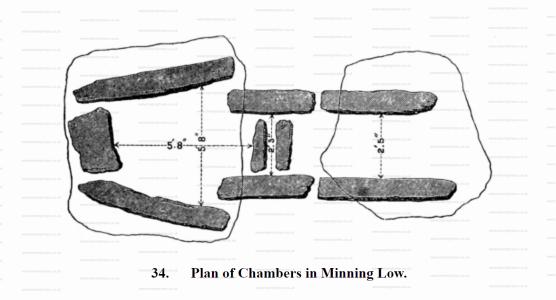

Though Gib Hill is interesting as the first of the high-level dolmens which we have met with in this country, Minning Low [Map] is a still more striking example of that class which we hinted at before as common in Aveyron (ante, woodcut No. 8), and which we shall meet with frequently as we proceed. When it first attracted the attention of antiquaries in 1786, Minning Low [Map] seems to have been a straight-lined truncated cone, about 300 feet in diameter, and the platform on its summit measured 80 feet across170. Its height could not be ascertained171. It was even then planted over with trees, so that these dimensions, except the breadth of the platform, are hardly to be depended upon, and since then the whole mound has been so dug into and ruined, that they cannot now be verified. On the platform at the top in 1786 there stood five kistvaens, each capable of containing-one body; and, so far as can be made out from Douglas' plates and descriptions, the cap stone of these was flush with the surface, or possibly, as at Gib Hill, they may have been a few inches below the surface, and, becoming exposed, may have been rifled as they were found; but this is hardly probable, because unless always exposed, it is not likely they would have been either looked for in such a situation, or found by accident. Below them—at what depth we are not told—a stone chamber, or rather three chambers, were found by Mr. Bateman, apparently on the level of the ground on the south side of the Barrow172. To use Mr. Bateman's own words ('Vestiges,' &c., p. 39): "On the summit of Minning Low Hill [Map], as they now appear from the soil being removed from them, are two large cromlechs, exactly of the same construction as the well-known Kit's Cotty-house, near Maidstone, in Kent. In the cell near which the body lay were found fragments of five urns, some animal bones, and six brass Roman coins, viz., one of Claudius Gothicus (270), two of Constantine the Great, two of Constantine, junior, and one of Valentinian. There is a striking analogy between this and the great Barrow at New Grange, described by Dr. Ledwich, of which a more complete investigation of Minning Low [Map] would probably furnish additional proofs." Mr. Bateman was not then aware that a coin of Valentinian had been found in the New Grange mound173, which is one similarity in addition.

Note 170. Douglas, 'Nenia Brittanica,' p. 168, pl. xxxv.

Note 171. If we knew its height we might guess its age. If it was 65 feet high, its angle must be 30 degrees, and its age probably the same as that of Silbury Hill. If 100 feet, and its angle above 40 degrees, it must have been older.

Note 172. 'Ten Years' Diggings,' p. 82.

Note 173. 'Petrie's Life,' by Stokes, p. 234.

The fact of these coins being found here fixes a date beyond which it is impossible to carry back the age of this mound, but not the date below which it may have been erected. The coins found in British barrows seem almost always those of the last Emperors who held sway in Britain, and whose coins may have been preserved and to a certain extent kept in circulation after all direct connexion with Rome had ceased, and thus their rarity or antiquity may have made them suitable for sepulchral deposits. No coin of Augustus or any of the earlier Emperors was ever found in or on any of these rude tumuli, which must certainly have been the case had any of them been pre-Roman. This mound is consequently certainly subsequent to the first half of the fourth century, and how much more modern it may be remains to be determined.

Be this as it may, if Mr. Bateman's suggestion that this monument is a counterpart of Kit's Cotty-house is correct—and no one who is familiar with the two monuments will probably dispute it—this at once removes any improbability from the argument that the last-named may be the grave of Catigren. The one striking difference between the two is, that Kit's Cotty-house is an external free-standing dolmen, while Minning Low [Map] is buried in a tumulus. This, according to the views adopted in these pages, from the experience of other monuments, would lead to the inference that the Kentish example was the more modern of the two. It is not, however, worth while arguing that point here; for our present purpose it is sufficient to know that both are post-Roman, and probably not far distant in date.

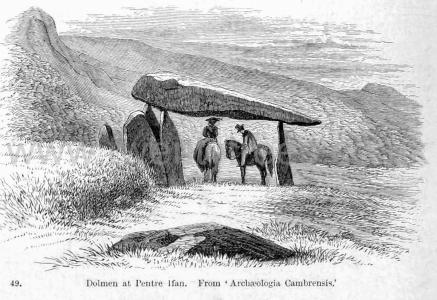

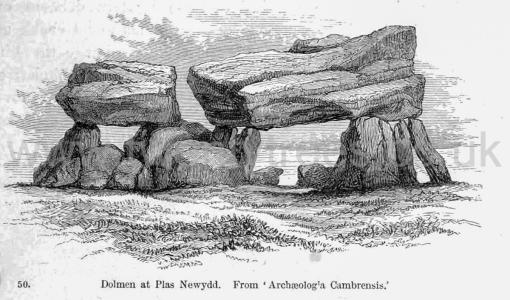

Almost all the so-called dolmens in the Channel Islands are of this class. One has already been given (woodcut No. 11), and it may safely be asserted that all chambers which were wainscoted with slabs, so as to form nearly perfect walls, and all that had complicated quasi-vaulted roofs were, or were intended to be, covered with mounds - more especially those that had covered pas- sages leading to them. There is, however, a very wide distinction between these sepulchral chambers and such a monument as this at Pentre Ifan [Map], in Pembrokeshire1. The top stone is so large that it is said five persons on horseback have found shelter under it from a shower of rain. Even allowing that the horses were only Welsh ponies, men do not raise such masses and poise them on their points for the sake of hiding them again. Besides that, the supports do not and could not form a chamber. The earth would have fallen in on all sides, and the connexion between the roof and the floor been cut off entirely, even before the whole was completed. Or, to take another example, that at Plas Newydd [Map], on the shore of the Menai Strait. Here the cap stone is an enormous block, squared by art, supported on four stone legs, but with no pretence of forming a chamber. If the cap stone were merely intended as a roofing stone, one a third or fourth of its weight would have been equally serviceable and equally effective in an architectural point of view, if buried. The mode of architectural expression which these Stone men best understood was the power of mass. At Stonehenge, at Avebury, and everywhere, as here, they sought to give dignity and expression by using the largest blocks they could transport or raise - and they were right; for, in spite of their rudeness, they impress us now; but had they buried them in mounds, they neither would have impressed us nor their contemporaries.

Note 1. 'Archæologia Cambrensis,' third series, xi. p. 284