Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Derbyshire Dales, Bakewell, Arbor Low

Arbor Low is in Bakewell, Derbyshire [Map].

Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Derbyshire Dales, Bakewell, Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]

Arbor Low Henge Barrow is also in Peak District Bronze Age Barrows.

Archaeologia Volume 7 Section XIII. The other low [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] stands on the right hand of the southern entrance into the area of the templeq. It stands upon the grand rampire, which is a very extraordinary position, and is not above three or four yards removed from the said entrance. This again is a considerable pile of earth, nearly as big as the former, and with the like hollow, or bason, in the area of its top, only that the water which was lodged in it, has, from time to time, run over the interior edge next the fosse, and worn it away. It is natural to imagine, that this low, so singularly situated on the rampire of the temple, must have been of a later conftrusion than the temple itself.

Note q. See the plate.

James Pilkington 1789. Having attempted to describe the figure and dimensions of this ancient monument, I shall now assign some reasons for regarding it as a Druidical temple or place of worship.

I believe it is generally allowed by antiquarians, that circular and ellyptical monuments; of this kind are of civil or religious institution; that they were either places of council, or courts of justice; or that they were designed or the rites of worship. Now upon examination there are found a few circumstances, respecting this in particular, which render it probable, that it was once used for the latter purpose. It seems reasonable to suppose from the number and size of the stones, lying near the center of the area, that there formerly Hood a cromlech or altar in this situation. One of them, which was most probably supported by the other two, measures three yards in length, and two in breadth, and is about one foot thick. Upon this large broad stone, it is very likely, that the sacrifices were offered. Perhaps the other stones within the area might be used as seats or supports for those, who attended the celebration of the rites of worship. As they seem to diverge from one common center, it has been imagined, that they were intended to represent the rays of the sun, and that this luminary was the object of devotion. This conjecture is ingenious and plausible. — But there is another circumstance, which renders it still more probable, that this ancient monument is a Druidical temple. A few years ago a transverse section was made of the barrow [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]], which has been mentioned, and in it were found the horns of a stag. Now there appears good ground to believe that the animal, to which they belonged, had been offered up in sacrifice. For as mounts of this kind are throughout the neighbouring country places of buried, we may reasonably suppose, that this in particular was employed as a repository for the bones of the victims, which were used in the celebration of religious rites.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. [Fol. 42] June 1st, 1824. Arborlow.2.

"Opened the tumulus at Arborlow [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] by driving a level thro, the N.W. side next to the ditch. We found the whole mass as described by Mr Mander of Bakewell (the companion of Major Rooke on its first examination 29th, June 1782) composed of common vachill or loose stones and earth, intermixed occasionally with lumps of clay. A few heads and jaw bones of rats were scattered among the stones, with a human tooth, some fragments of bone probably human, and some small remains of charcoal. We penetrated 2 or 3 ft. below the depth to which Major Rooke had previously excavated it, when we came to a sandy soil with a stratum of clay beneath it, same as that of the natural soil around the tumulus. We cleared away the whole centre of the mound without making any discovery, or meeting with any circumstance, which would induce us to suppose it had been a place of sepulture. I feel certain, that whatever (from the circumstance of our finding a few bones, and a human tooth) might have been its destination in later times, its original design was not as a place of burial, but was some necessary appendage to the temple."

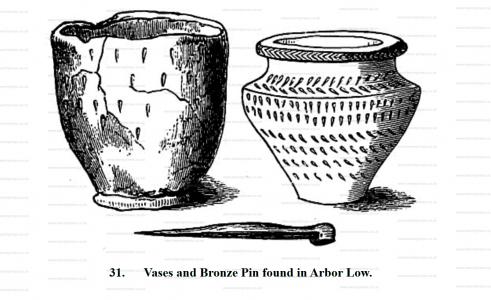

Briefly referred to, Vestiges, p. 31, and again on p. 64, where Mr. Mitchell is stated to have been associated with Mr. W. Bateman. The second of these pages gives an account of the successful opening of this barrow by Mr. T. Bateman on May 23rd, 1845 when a cist containing burnt human bones and two small vases were found.

Thomas Bateman 1824. June 1st, 1824, an ineffectual attempt was made to open the immense tumulus [Map] forming part of the temple of Arbor Lowe [Map]. A deeper cutting was made in the same direction as the one made by Major Rooke in 1782, which was equally abortive; the only articles found by the Major being the almost universal rats' bones and part of a stag's horn; on the later attempt nothing occurred but one human tooth and some animal bones.

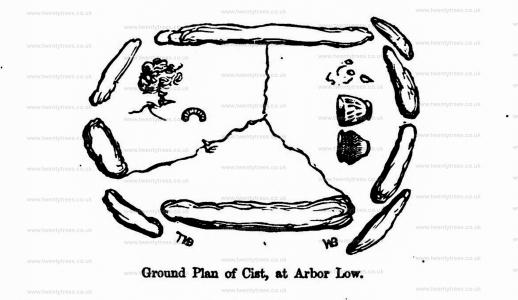

Thomas Bateman 1845. The 23d of May, 1845, is an important day in the annals of barrow-digging in Derbyshire, as on that day was made the discovery, so long a desideratum, of the original interment in the large tumulus [Map], which forms one side of the southern entrance to the temple of Arbor Lowe [Map], and which had been unsuccessfully attempted on previous occasions by three parties of antiquaries: first, about 1770, by the occupier of the land whereon the temple is situated; secondly, in 1783, by the celebrated archaeologist. Major Rooke (see p. 31, 1st Jun 1824), who laboured with no effect for three days; and thirdly, on the 1st and 2d of June, 1824, by Mr. Samuel Mitchell (age 42) and Mr. William Bateman, who succeeded no better (see p. 31). But, to return to the narrative. Operations were commenced on the day before mentioned, by cutting across the barrow from the south side towards the centre. A shoulder-blade and an antler of the large red deer were found in this excavation, which also produced an average quantity of rats' bones. On reaching the highest part of the tumulus, which owing to the soil and stones removed in the former excavations, is not in the centre, but more to the south, and is elevated about four yards above the natural soil, a large, flat stone was discovered, about five feet in length by three feet in width, lying in a horizontal position, about eighteen inches higher than the natural floor. This stone being cleared and carefully removed, exposed to view a small six-sided cist, constructed by ten limestones, placed on one end, and having a floor of three similar stones, neatly jointed. It was quite free from soil, the cover having most effectually protected the contents, which were a quantity of calcined human bones, strewed about the floor of the cist, all which were carefully picked up, and amongst them were found a rude kidney-shaped instrument of flint, a pin made from the leg-bone of a small deer, and a piece of spherical iron pyrites.

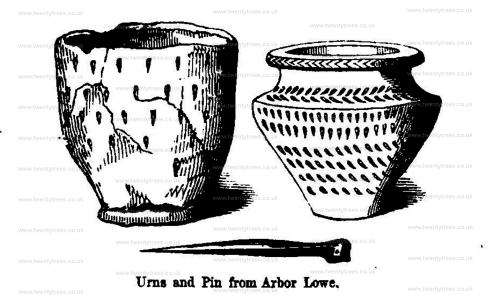

At the west end of the cist were two urns of coarse clay, each of which was ornamented in a peculiar and widely dissimilar manner. The larger one had fallen to pieces from the effects of time and damp, but has since been restored, and is a very elegant vase; the smaller was taken out quite perfect, and is of much ruder design and workmanship. In addition to these urns, one piece of the ornamented upper edge of another, quite distinct from either of them, was found. The floor of the cist was laid upon the natural soil and the cist was strewed with rats' bones, both within and without.

Thomas Bateman 1845. On the 16th of June, 1845, the researches at Arbor Lowe were resumed, by cutting through the part of the tumulus [Map] still remaining unexplored. But as nothing more than a few pieces of stag's horn were found, it is reasonable to suppose that the cist and urns previously discovered formed the primary and only interment in this immense and (from its connexion with the druidical temple) most important barrow.

Section II Circles. On the east side of the southern entrance is a large barrow [Map], standing in the same line of circumference as the vallum, but wholly detached except at the base. This barrow has been several times unsuccessfully examined, and remained an antiquarian problem until the summer of the year 1845, when the original interment was discovered, of a nature to prove beyond doubt the extreme antiquity of the tumulus, and consequently of the temple.

Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume 16 Page 101. At the south-east corner, about fifty feet from the southern entrance, is another barrow or tumulus [Map], projecting from the exterior of the agger, in which a vase was found, of British time;

Ten Years' Digging Observations on Celtic Pottery. The third division, comprising the vases for food, includes vessels of every style of ornament, from the rudest to the most elaborate, but nearly alike in size, and more difficult to assign to a determinate period than any other, from the fact of a coarse and a well-finished one having several times been found in company. They occur both with skeletons and burnt bones; perhaps more firequendy with the former, where they are often found near the head. Where two have been found, it has generally been with burnt bones, and probably indicates the combustion of two bodies. The woodcuts show two found in the barrow on the circle at Arbor Low [Map], in 1845, with a ground plan of the cist indicating their position.

Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter IV. There is another very interesting addition at Arbor Low, which is wanting at Penrith, this is a tumulus [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] attached unsymmetrically to the outer vallum. This was, after repeated attempts, at last successfully excavated by the Messrs. Bateman, and found to contain a cist of rather irregular shape, in which were found among other things two vases167 one of singularly elegant shape, the other less so. In themselves these objects are not sufficient to determine the age of the barrow, but they suffice to show that it was not very early. One great point of interest in this discovery is its position with reference to the circle. It is identical with that of Long Meg with reference to her daughters, and perhaps some of the stones outside Avebury, supposed to be the commencement of the avenue, may mark the principal places of interment.

Note 167. Bateman, 'Vestiges,' p. 65.

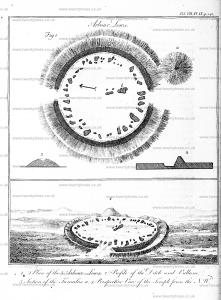

John Lubbock 1879. The celebrated Temple of Arbor Low, the most important monument of the kind in this part of England, consists of a circle of large, unhewn limestones surrounded by a deep ditch, outside of which rises a lofty vallum. The stones composing the circle are rough, unhewn masses, about thirty or forty in number; though as several are broken, this cannot exactly be determined; they are from six to eight feet in length, by about three or four feet in breadth at the widest part. At present they are all lying on the ground, and it is doubtful whether they were ever upright. Within the circle are some smaller scattered stones, and in the centre are three larger ones, which may, perhaps, have originally formed a dolmen, or sepulchral chamber. The central platform is 167 feet in diameter. The width of the fosse is about 18 feet; the height of the bank or vallum on the inside (though much reduced by the unsparing hand of Time), is still from 18 to 24 feet. The vallum is chiefly formed of the earth thrown out of the ditch, with a little from the ground which immediately surrounds the exterior of the vallum; thus adding to its height, and to the imposing appearance it presents to any one approaching from a distance. To the enclosed area are two entrances, each of the width of ten or twelve yards, and opening towards the north and south. On the east side of the southern entrance is a large barrow [Map], holding, in the opinion of some archaeologists, the same relation to the circle as Long Meg [Map] to the circle of stones [Map] near Penrith, known as her "daughters." This mound was first attacked in 1770, by the then occupier of the farm; secondly, in 1782, by Major Rooke; and thirdly, in 1824, by Mr. William Bateman; but none of these gentlemen succeeded in discovering the interment. At length, in 1845, Mr. Thomas Bateman was more fortunate.

John Lubbock 1879. He commenced by cutting a trench across the barrow [Map] from the south side. In the operation a shoulder-blade and antler of red deer were discovered, and also a number of water-rats' bones. On reaching the highest part of the tumulus, which was elevated about four yards above the natural soil, a large flat stone was discovered, about five feet in length, by three feet in width, lying in a horizontal position, about eighteen inches above the natural floor. This stone was cleared, when a small six-sided cist was exposed, constructed of ten limestone blocks, which were placed on one end, and having a floor of three similar stones. The chamber was quite free from soil, the cover having prevented the entrance of earth, and protected the contents, which were a quantity of calcined human bones, strewed about the floor of the cist; amongst which were found a rude kidney-shaped instrument of flint, a pin made from the leg-bone of a small deer, and a piece of spherical iron pyrites. At the west end of the cist were two ornamented, but dissimilar, urns of coarse clay. One had fallen to pieces, but has since been restored, and is of an elegant form; the other was taken out quite perfect, and is of much ruder design and workmanship. In addition to these urns, a piece of the ornamented upper edge of another vase, quite unlike the others, was found, The floor of the chamber was laid - the natural soil, and the cist was strewed with rats' bones, both within and without. The pin had probably been used as a brooch, while the flint and iron pyrites, which have been found in association in other barrows, probably served for procuring fire. The urns belong to the type which have been called food vessels, to distinguish them from the cinerary urns in which the ashes of the deceased were placed. They may have contained two sorts of food, or food and drink; or, as Mr. Bateman supposes, the presence of two may indicate a double burial.

Harold Gray 1902. On the south-east vallum a, Bronze Age tumulus [Map] was constructed undoubtedly from material derived from the original monument of Arbor Low. As previously stated, no bronze was found here or in Gib Hill [Map], just over 1,000 feet distant; but their other contents point to a Bronze Age culture, probably not particularly late. If the "finds" from this tumulus1 on the vallum of Arbor Low are to be regarded as belonging to the Early Bronze period, "then," as Mr. Henry Balfour said at Belfast, "the probability of the circle being of Neolithic date is much increased."

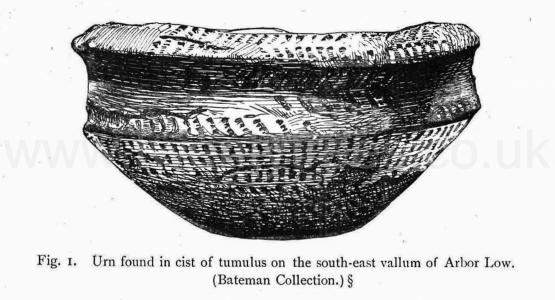

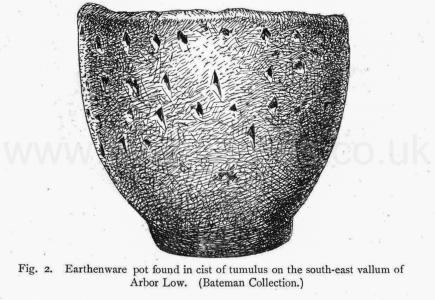

Note 1. The absence of bronze in this interment does not necessarily give an Early Bronze Age date for the burial, for bronze was rarely found with interments even in the fully-developed Bronze Age. The two pots found in the tumulus (figs. 1 and 2) are not "beakers," or drinking-vessels, which the Hon. John Abercromby has recently classified as being the oldest Bronze Age ceramic type in Britain, Journal of the Anthrolologieal Institute, xxxii. 373.)

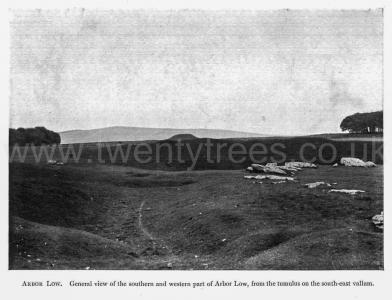

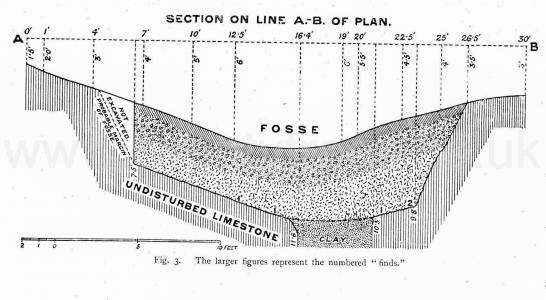

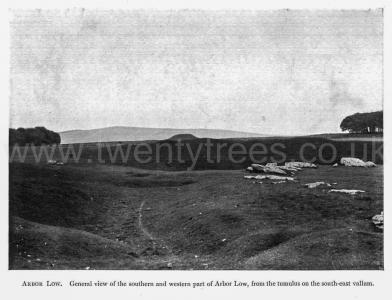

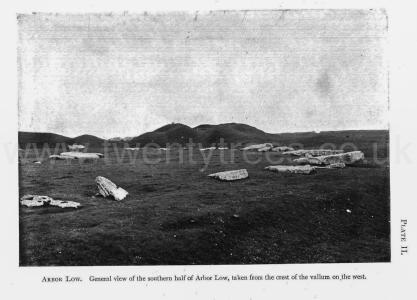

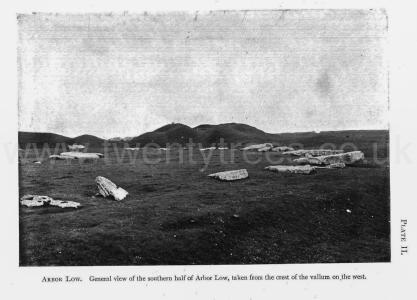

Harold Gray 1902. These urns are figured in the accompanying illustrations, figs. 1 and 2. Fig. 1 was found filled with burnt bones. It is unusually wide and low: 4½ inches high, 9 inches diameter at top, 4 inches diameter at base. The other pot, fig. 2, found with it, is 4½ inches high, 5½ inches diameter at top, 3 inches at bottom. In June, 1845, the digging of this tumulus [Map] was resumed, but nothing further was discovered beyond a few pieces of deer-horn. Mr. Bateman never took the trouble to fill-in his excavation properly, the result being that four or five little knolls exist round the top of the tumulus, bounding a rather deep depression in the centre (see photograph, plate II.). In addition to this, he threw some of his débris into the ditch, clearly shown in the plan and photograph plate I. The formation of this tumulus, which is probably of somewhat later date than the vallum, has caused a gap to occur in the vallum on either side of the mound. There is also another irregularity in the form of the rampart to the north of the tumulus, caused by a kind of spur which extends halfway across the fosse. All along the crest of the eastern and north-eastern vallum are irregular depressions, sufficient material for filling which may be observed at intervals in ledges and patches along the base of the inner side of the east and north-east vallum, or, in other words, along the outer edge of the fosse in these parts. The only feasible explanation for this seems to be that Messrs. Bateman and Isaacson, elated by their success in finding the interment in the tumulus close to, pursued their investigations along the adjacent crest of the vallum at intervals, shovelling the material inwards down the slope of the rampart.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. The tumulus [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] at the temple on Arberlow was begun to be opened by Major Rook, June 26, 27, 28. Common Rachell, in which small parts of animal bones, parts of stag horns, some of birds with claws, some of mice. Clay in some parts. The name given to this place by the country people Arbour lows Rink — William Normanshaw of Middleton by Youlgreave says he has seen some of these stones erect.

Harold Gray 1902. On the south-east, adjoining the external face of the vallum and partly resting on it, a tumulus [Map] stands, the summit 7½ feet above the surrounding turf-level (see photograph, plate II.). This barrow was first attacked in 1770 by the then occupier of the farm, without success. Likewise to 1782 by Major Rooke, assisted by John Manders, and in 1824 by William Bateman and Samuel Mitchell, of Sheffield. A fourth attempt, made in 1845, by Thomas Bateman and Rev. S. Isaacson, resulted in the discovery of a limestone cist, which has been frequently described1. It contained calcined human bones, a bone pin2, pyrites and flint, and two small urns3, differing considerably in style and ornamentation, but undoubtedly of Bronze Age manufacture, and probably rather early in that period4.

Note 1. "Arbor Low," by Sir John Lubbock, the Reliquary, xx. 8l-85; Bateman's Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire, 64-66 and 74; and Winchester Volume of the British Archrological Association (1845), 197-204.

Note 2. Figured in Fergusson's Rude Stone Monuments, r4r, and Vestiges, 65,

Note 3. These relics are in the Sheffield Museum. The urns are reproduced by kind permission of Mr. E. Howarth, the curator.

Note 4. Dr. Brushfield calls my attention to the very misleading representation of this urn in Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire, p. 65.-Ed. D.A.N.E S

Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Derbyshire Dales, Bakewell, Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map]

Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle is also in Peak District Henges, Peak District Stone Circles, Stenness Type Cove.

Between 2500BC and 2000BC. Barbed-and-tanged flint arrowhead found at Arbor Low [Map]. In the collection of Buxton Museum and Art Gallery [Map].

Between 2500BC and 700BC. Stone axehammer found at Arbor Low [Map]. In the collection of Buxton Museum and Art Gallery [Map]. Width 56mm; length 177mm; depth 57mm; diameter of hole 27mm.

Between 2500BC and 1500BC. Discoidal flint knife found at Arbor Low [Map]. In the collection of Buxton Museum and Art Gallery [Map]. Height 11mm; width 74mm; length 97mm; depth 3mm; diameter mm. This tool was purchased from a local farmer by Micah Salt in 1897. Micah Salt (1847-1915) was a tailor in Buxton who had a great interest in archaeology.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. 10 Jun 1761[Fol. 45.]

Copied from MS of John Mander, of Bakewell.

Arbourlows [Map] viewed by Mr Pegge and myself, 10 June 1761.

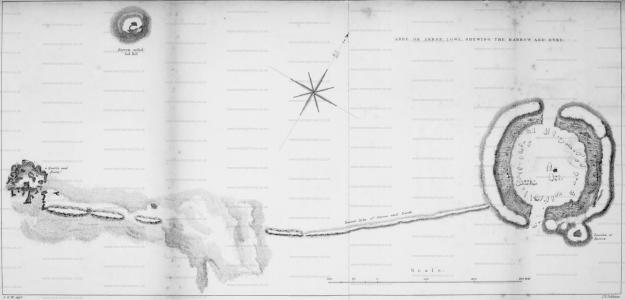

There are 2 in the enclosed commons adjoining One Ash ground, the great one is environed (a) by a great circular rampire, whose height sloping is about 7 yards, the foss four yards (b) over, the area (c) flat of 50 yards diameter; round which are 32 very large limestone slabs formerly erect, now flat. This Mr Pegge called a British temple. It has two entrances, one to the East, another to the West1. From that to the East runs a smail rampire, winding south westwardly to the 2nd low (D) at the distance of about 4 or 500 yards2. On the NE3 side of the temple near the last entrance upon the rampire stands a large low, or mount of earth supposed a great barrow and is properly the low.

The low D4 is about 18 feet diameter at top, with a large hollow in the middle of its area summitt after the form of a bason, on the S side is a small faint rampire5 of earth with several breaks in it running across the field (at the distance of about 70 feet from the low) from the wall on the W, and across under the wall on wall to the E. N.B., On the W side of the western wall we could find no traces of this rampire, nor any place where it turned. This rampire crossing the Eastern wall as was said before passes quite to the foot of the great rampire of the temple."

Note 1. Mr Manders evidently had the compass bearings on the plan referred to in this MS., wrong. The entrances of the circle are nearly due north and south, and the tumulus is on the south-east.

Note 2. Gib Hill [Map], but its actual distance from the circle is about 300 yds. It is constantly stated by the older writers that this tumulus was connected with the circle by a "rampire." This, however, upon leaving the latter, does not point to Gib Hill [Map], but has a southerly course for about 200 yards, after which it curves to the west, but with a bearing considerably south of the latter, and is then lost. The recent excavations proved that it consists of a small bank and ditch.

Note 3. This tumulus is on the sonth-east.

Note 5. From personal observations, this is very doubtful (J.W.).

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. 29 Jun 1782. Arber low [Map] 29: June 1782.

Qy of its addition Rink? Mr. Rook thinks this to be the most ancient and capital monument of antiquity in the Kingdom, and upon a plan full as large as Stonehenge, but vastly more ancient. That in every such place each stone had its name, before which stones the respective chiefs stood in their general assemblies, and every one knew his own stone, which bore his name of office, as King stone, &c. Rinch, Ringh, Ring from Winshew Curium rotendum. The temple here is certainly round, and if no circumstance of a barrow appears in the Mount now (June 29th 1782) opening, it should seem to be more like a court, when the assemblies of the ancient Britons with their chiefs were used to be held. Compare it with Vernometum in Leicestershire.

Archaeologia Volume 7 Section XIII. A Disquisition on the Lows or Barrows in the Peak of Derbyshire, particularly that capital British Monument called Arbelows [Map]. By the Rev. Mr. Pegge (age 80).

James Pilkington 1789. In this hamlet is one of the most striking monuments of antiquity, which is to be met with in Derbyshire. It is about a mile and a half distant from Newhaven, and is known by the name of Arbelows, or Arbor-low [Map].

This ancient remain consists of an area, encompassed by a broad ditch, which is bounded by a high mound or bank; and the form of the whole is nearly that of an ellypsis, or imperfect circle.

The area B. B. measures from east to west forty- fix yards, and fifty-two in the contrary direction. The width of the ditch C. C. is fix, and the height of the bank D. D. on the inside five yards. The height is continually varying throughout the whole circumference; but is at a medium what I have now mentioned.

The bank has evidently been formed from the soil, which has been thrown out of the ditch, but it is not carried entirely round the area. To the north and south there is an opening, or passage F. F. about fourteen yards wide. On the east side of the southern one is also a small mount or barrow E. This stands in the same line of circumference with the bank, but is entirely detached from it.

Arthur Jewitt 1811. Newhaven Inn

This inn is a late erection of the Duke of Devonshire's, besides which, he has just finished another, at a little distance from it; the latter being chiefly designed for the accommodation of carriers, &c. and the former, for travellers of a superior class.

At a short distance from Newhaven, is perhaps the finest piece of antiquity in this part of the country; it is called Arbor-lowe [Map], or Arbe-lowes, and is supposed to be the remains of a druidical temple. It is composed of a circle of large stones, about 150 feet in diameter, surrounded by a bank, the sloping side of which measures nearly 33 feet. This curiosity is particularly described by Mr. Pilkington, in his Present State of Derbyshire, and is illustrated by an accurate view of it, as it stood about the year 1780.

A mile beyond Newhaven Inn, and about the same distance from the road, toward the right hand, is another antiquity, also described by Mr. Pilkington, called Wolves'-cote-lowe, which stands on the top of Wolves'-cote, ( or as it is there called Wuss-cote ) hill. It is a barrow very much resembling that described at Chelmorton; the circumference of its base is about 70 yards.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. [Fol. 44.]

June 1st 1824. Examined William Normanshaw of Middleton aged 74 years, son of W. Normanshaw mentioned by Pegge. He says he has repeatedly heard his father (who died about 20 years ago at the age of 90) say that he remembered the stones in the circle at Arborlow [Map]; many of them standing, more erect than they do now1. Does not think they have undergone much alteration in position in his own remembrance. Recollects Major Rook opening the low they found the horns of a stag - once dug into the side of the barrow belonging to T. Bateman Esquire for stone, when he found the scull of a human being.

Note 1. This tends to confirm Pilkington's statement: I have been informed, that a very old man, living in Middleton, remembers, when he was a boy, to have seen them (the stones), standing obliquely upon one end." - A View of the Present State of Derbyshire, II., p. 460 ( 1789). Statements of this sort, however, must be accepted tun grano salis [with a grain of salt]. An old man employed in Mr. H. St. George Gray's recent excavation assured him that he had seen five of the stones standing when he was a boy and had sheltered under them. But it should be noticed that none of these statements imply that any of these stones were seen standing vertically on end. They simply imply that in comparatively recent times some were obliquely elevated, a conceivable attitude in the process of gradual subsidence.

Stephen Glover 1831. Between two and three miles north—east of Newhaven, at a little distance beyond the Roman road from Buxton to Little Chester, is one of the most remarkable monuments of antiquity in Derbyshire. This is the Arbor-Low or Arbelows [Map], a druidical circle, surrounded by a ditch and vallum. Its situation, though considerably elevated, is not high as some eminences in the neighbouring country ; yet it commands an extensive view, especially to the north-east. The area, encompassed by the ditch, is about fifty yards in diameter, and of a circularfurm ; though, from a little declination of the ground towards the north, it appears somewhat elliptical, when viewed from particular points. The stones which compose the circle are rough and unhewn masses of limestone, apparently thirty in number; but this cannot be determined with certainty, as several are broken. Most of them are from six to eight feet in length, and three or four broad in the widest part; their thickness is more variable, and their respective shapes are different. They all lie on the ground, and generally in an oblique position; but the opinion that has prevailed, of the narrowest end of each being pointed towards the centre, in order to represent the rays of the sun, and prove that luminary to have been the object of worship, must have arisen from inaccurate observation: for they almost as frequently point towards the ditch as otherwise. Whether they ever stood upright, as most of the stones of druidical circles do, is an enquiry not to determine; though Mr. Pilkington was informed, that a very old man living in Middleton, remembered, when a boy, to have seen them standing obliquely upon one end. This secondary kind of evidence does not seem entitled to much credit as the view of the stones themselves and their relative situations are almost demonstrative of the contrary. Within the circle are some smaller stones scattered irregularly and near the centre are three larger ones erroneously supposed to have once formed a cromlech The width of the ditch which immediately surrounds the area on which the stones are placed is about six yards the height of the bank or vallum on the inside is from six to eight yards but this varies throughout the whole circumference which on the top is nearly two hundred and seventy yards. The vallum seems to have been formed of the earth thrown up from the ditch. To the enclosed area are two entrances each of the width of ten or twelve yards and opening on the north and south. On the east side of the southern entrance is a large barrow standing in the same line of circumference as the vallum but wholly detached excepting at the bottom. This barrow was opened in June 1782 by H Rooke esq and the horns of a stag were discovered in it and June 1 1824 by Mr Samuel Mitchell (age 27) of Sheffield and the engraving here inserted is copied from an accurate drawing made by that gentleman.

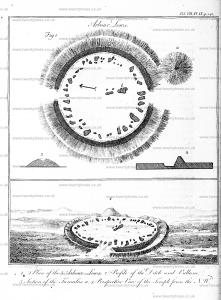

Section II Circles. By far the most important, as well as the most uninjured, remain of the religious edifices of our barbarous forefathers that is to be found in the midland counties, is to be seen a short distance to the left hand of the turnpike road from Buxton to Ashbourne, at about an equal distance from each of those towns. This is the famous temple of Arbor Lowe, or Arbe Lowe [Map], as it is generally called by the country people; it is a circle of large unhewn limestones, surrounded by a deep ditch, outside of which rises a large and high vallum. Its situation, though considerably elevated, is not so high as some eminences in the neighbouring country; yet it commands an extensive view, especially towards the north-east, in which direction the dreary and sombre wastes of the heath-clad East Moor are perfectly visible, though distant about fifteen miles; were it not for a few stone fences, which intervene in the foreground, the solitude of the place and the boundless view of an uncultivated country are such as almost carry the observer back through a multitude of centuries, and make him believe that he sees the same view and the same state of things as existed in the days of the architects of this once holy fane.

Section II Circles. The feelings on visiting this place [Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map]], on a warm summer's day, when there is no sound to disturb the solitude, save the singing of the lark, and now and then the cry of the plover (both which here abound), are truly delightful. But to resume the description; the area encompassed by the ditch is about fifty yards in diameter, and of a circular form; though, from a little declination of the ground towards the north, it appears somewhat elliptical when viewed from particular points. The stones which compose the circle are rough, unhewn masses of limestone, apparently thirty in number; but this cannot be determined with certainty, as several of them are broken; most of them are from six to eight feet in length, and three or four broad in the widest part.; their thickness is more variable, and their respective shapes are different and indescribable. They all lie upon the ground, many in an oblique position, but the opinion that has prevailed, of the narrowest end of each being pointed towards the centre, in order to represent the rays of the sun, and prove that luminary to have been the object of worship, must have arisen from inaccurate observation, for they almost as frequently point towards the ditch as otherwise; whether they ever stood upright, as most of the stones of druidical circles do, is an inquiry not easy to determine; though Mr. Pilkington was informed that a very old man, living in Middleton, remembered, when a boy, to have seen them standing obliquely on one end; this secondary kind of evidence does not seem entitled to much credit, as the soil at the basis of the stones does not appear to have ever been removed to a depth sufficient to ensure the possibility of the stones being placed in an erect position. Within the circle are some smaller stones scattered irregularly, and near the centre are three larger ones, by some supposed to have formed a cromlech or altar, but there are no perceptible grounds for such an opinion. The width of the ditch, which immediately surrounds the area on which the stones are placed, is about six yards; the height of the bank or vallum, on the inside (though much reduced by the unsparing hand of time), is still from six to eight yards; but this varies throughout the whole circumference, which, on the top, is about two hundred and seventy yards. The vallum is chiefly formed of the earth thrown out of the ditch, besides which a little has been added from the ground which immediately surrounds the exterior of the vallum, thus adding to its height, and to the imposing appearance it presents to any one approaching from a distance. To the inclosed area are two entrances, each of the width of ten or twelve yards, and opening towards the north and south.

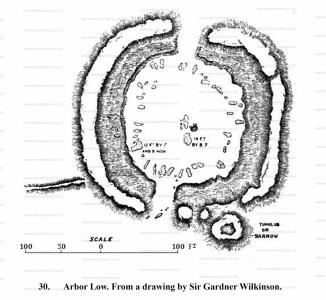

Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume 16 Page 101. and a still more remarkable instance occurs at Arbe Low [Map]1 in Derbyshire. (See pl. 9.) This has two entrances. The inner platform is 167 feet in diameter, and the ditch is 18 feet broad at the bottom. The stones are small compared to those of Abury, the largest belonging to the circle measuring 13 feet by 7; while one of the largest at Abury measures from 14 to 18 feet in length, 12 feet 3 inches in height, and 7 feet (varying to 2 feet 4 inches) in thickness : and the platform of Abury has an average diameter of 1,130 feet. The agger of Arbor Low is still about 15 to 18 feet high, or from 20 to 24 to the bottom of the ditch; and the circumference at the top of it is nearly 820 feet.

It has been stated that the narrow end of the stones points to the centre of the circle; but as Mr. Bateman2 justly remarks, it points as often towards the ditch ; and instead of radiating to or from the centre, as if to imitate the sun's rays, they lie in the direction in which they have fallen : for it is evident that they originally stood upright, as in other sacred circles; and the notion of those who doubt it is evidently erroneous, as some are even now in an oblique position, the upper end not having yet reached the ground ; confirming the statement of an old man, mentioned by Mr. Bateman, who declared that he had seen them standing obliquely on one end. The entrances open towards the north and south, and the two passages leading from them to the platform measure each about 27 feet in breadth.

Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter IV. The principal monument of this group is well-known to antiquaries as Arbe or Arbor Low [Map], and is situated about nine miles south by east from Buxton, and by a curious coincidence is placed in the same relative position to the Roman Road as Avebury. So much is this the case, that in the Ordnance Survey—barring the scale—the one might be mistaken for the other if cut out from the neighbouring objects. Minning Low [Map], however, which is the pendant of Silbury Hill in this group, is four miles off, though still in the line of the Roman road, instead of only one mile, as in the Wiltshire example. Besides, there is a most interesting Saxon Low at Benty Grange, about one mile from Arbor Low. Gib Hill, Kens Low, Ringham Low, End Low, Lean Low, and probably altogether ten or twelve important mounds covering a space five miles in one direction, by one and a half to two miles across.

Note 165. First described in the 'Archæologia,' vol. viii. p. 131 et seq., by the Rev. S. Pegge, in 1783.

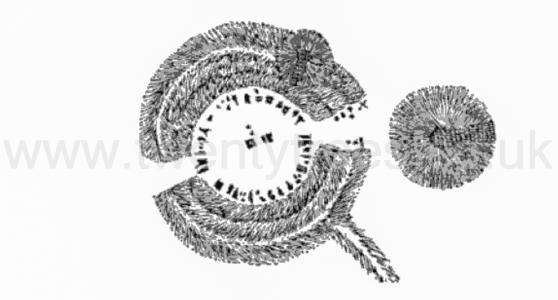

Arbor Low consists of a circular platform, 167 feet in diameter, surrounded by a ditch 18 feet broad at bottom, the earth taken from which has been used to form a rampart about 15 feet to 18 feet high, and measuring about 820 feet in circumference on the top. The first thing that strikes us on looking at the plan (woodcut No. 30) is that, in design and general dimensions, the monument is identical with that called "Arthur's Round Table," at Penrith. The one difference is that, in this instance, the section of the ditch, and consequently that of the rampart, have been increased at the expense of the berm; but the arrangements of both are the same, and so are the internal and external dimensions. At Arbor Low there are two entrances across the ditch, as there was in the Cumberland and Dumfriesshire examples. As mentioned above, only one is now visible there, the other having been obliterated by the road, but the two circles are in other respects so similar as to leave very little doubt as to their true features.

John Lubbock 1879. Arbor Low [Map]1 By Sir John Lubbock (age 44), Bart., M.P., F.R.S., F.S.A.

Note 1. I have to express my profound indebtedness to Sir John Lubbock, for permitting the "Reliquary" to be the medium of giving to the antiquarian world this important paper, read by him, on the spot-at Arbor Low itself-before the Members of the British Association, on the 23rd of August, in the present autumn. Sir John in the hand, placed his MS. in my hands for publication, and I feel that by so doing he has not only conferred a favour on myself, but a great boon on all of archæology. L. JEWITT (age 62).

Harold Gray 1902. Arbor Low Stone Circle [Map] Excavations in 1901 and 1902. By H. St. George Gray (age 29)

The following is an abstract of a paper communicated to the Society of Antiquaries by Mr. Gray, in April, 1903, and printed in Archæologia, Vol. lviii., pp. 461-498. By kind permission of the Society liberal use has been made of Mr. Gray's paper, and the proofs have been revised by him. We are further indebted to the society for the loan of most of the illustrations in Archæologia, but the size of these pages has necessitated considerable reduction of the plan.

Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map]. Aubrey Burl, in his book "A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany", states "The three sided Cove is now prostrate, two huge sides tumbled outwards, a long low stone on edge like a sill or septal slab between them at the east and other little stones nearby. A skeleton of a man about 5ft 5ins tall was buried againbst the eastern corner. Immediately east was a deep pit with a human armbone in it. "It is possible", wtrote the excavator, "That a skeleton or skeltons may have been removed from here".

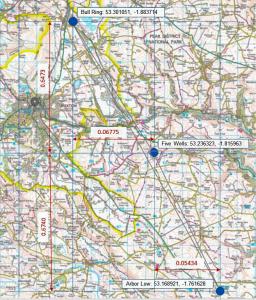

Arbor Low Five Wells Bull Ring Monument describes a possible prehistoric single monument formed from Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map], Five Wells Chambered Tomb [Map] and the Bull Ring Henge [Map] that form the same shape as the constellation Orion's Belt.

Other prehistric monuments including the Thornborough Henges, and, possibly, the Giza Pyramids appear to be similar. There are theories about there being a 'Cult of Orion' around 2400BC. Both Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map] and Bull Ring Henge [Map] can be seen from Five Wells Chambered Tomb [Map] albeit not with the naked eye during daylight - a camera with a long lens is needed. In darkness a bonfire would make both easily visible.

Taking the positions of each map from Historic England's listing the angle between the monuments is 172 degrees which is consistent with the angle of Orion's Belt. The angle of Orion's belt may have changed over time - difficult to find an exact figure. And, of course, difficult to be precise as to the centre of each monument so error is likely. I couldn't find a description of the linear distance between the stars seen from earth. If anyone has better information please email email@twentytrees.co.uk.

The Reliquary Volume 18 Page 49. On Arbor Low [Map] IV by William Henry Goss.

Caesar, speaking of human sacrifices among the Gauls, says, "Those who are afflicted with any grievous distemper, or whose lives are hazarded in war or exposed to other dangers, either offer up men for sacrifices, or vow to do so ; and they make use of the Druids for their priests on such occasions, imagining their gods are to be satisfied no other way for sparing their lives than by offering up the life of another man." We have learned that the Druids of Gaul came into Britain for initiation into the mysteries of their dreadful office. Is it not possible that some of them took lessons within this same circle of Arbor Low [Map]? Tacitus mentions that the ancient Germans sacrificed human victims to their gods, and Procopius Ceesariensis affirms that in his day, in the sixth century of our Lord, the Druids of Gaul still offered human sacrifices, and I have already referred to Charlemagne's edict against the practice so late as the year 789 A.D.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal. Some Notes of Arbor Low [Map] and other Lows in the High Peak by Arthur T Matthews

Many excellent descriptions of Arbor Low have been published, but a few points, which appear to me of interest, have not, so far as I have been able to ascertain, been noted.

Arbor Low is about a mile from Parsley Hay Station, on the northerly slope of a hill which rises somewhat to the south, the centre of the circle,, being 1,231 feet above the Ordnance Datum.

Why was it not placed on the summit?

Arbor Low is in latitude 53° 10¼ N. and longitude 1° 45½ W.; Stonehenge is in latitude 51° 11 N. and longitude 1° 49 W. (The latitude and longitude of Arbor Low are taken from the Ordnance map; those of Stonehenge are as given in Stanford's, London Atlas.)

Thus Arbor Low is nearly due north of Stonehenge, and still more exactly two degrees of latitude to the north. The division of the circle into 360 degrees is very ancient; it was used by Ptolemy in the Almagest, and probably long before his time, so that the double coincidence is noteworthy.

In the middle of the southern gateway of Arbor Low there is an isolated stone right away from the circle," broken off, but with the base still in position. This stone is sharply pointed, and is due south of the centre of the "circle". I take it to have been the marker of high noon. This stone is shown on Mr. Gray's plan, but is not numbered call it the south pointer,

Blacks Guide to Derbyshire. Parsley Hay, where, on getting out of the train, one sees hardly any houses but the forlorn little terminus, and must turn up the road for a modest refreshment room, is also the station for Arbor Low [Map], the Derbyshire Stonehenge, that stands conspicuously elevated a mile to the east on the south of the Bakewell Road. Its Druidical circle, which comes next in importance to those of Stonehenge and Avebury, consists of overthrown stones, mostly 6 to 8 feet high, lying disordered on a platform about 50 yards in diameter, surrounded by a wide ditch. On the east side of the south entrance is a large barrow, the exploration of which has proved the antiquity of this "high place." Some quarter of a mile westwards is another conical tumulus known as Gib Hill [Map], connected with Arbor Low by a bank of earth. On this side the Roman road can be traced, taking its straighter line near the modem turnpike, with which it in part coincides.

Only the present remoteness of Arbor Low prevents it from being more often visited. "Its situation, though considerably elevated, is not so high as some eminences in the neighbouring country; yet it commands an extensive view, especially towards the north-east, in which direction the dreary and sombre wastes of the heath-clad East Moor are perfectly visible, though distant about 15 miles; were it not for a few stone fences, which intervene in the foreground, the solitude of the place and the boundless view of an uncultivated country are such as almost carry the observer back through a multitude of centuries, and make him believe that he sees the same view, and the same state of things as existed in the days of the architects of this once holy fane." — Bateman's Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire.

Europe, British Isles, North-Central England, Derbyshire Dales, Bakewell, Arbor Low, Gib Hill Barrow [Map]

Gib Hill Barrow is also in Peak District Bronze Age Barrows.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. 10 Jun 1761[Fol. 45.]

Copied from MS of John Mander, of Bakewell.

Arbourlows [Map] viewed by Mr Pegge and myself, 10 June 1761.

There are 2 in the enclosed commons adjoining One Ash ground, the great one is environed (a) by a great circular rampire, whose height sloping is about 7 yards, the foss four yards (b) over, the area (c) flat of 50 yards diameter; round which are 32 very large limestone slabs formerly erect, now flat. This Mr Pegge called a British temple. It has two entrances, one to the East, another to the West1. From that to the East runs a smail rampire, winding south westwardly to the 2nd low (D) at the distance of about 4 or 500 yards2. On the NE3 side of the temple near the last entrance upon the rampire stands a large low, or mount of earth supposed a great barrow and is properly the low.

The low D4 is about 18 feet diameter at top, with a large hollow in the middle of its area summitt after the form of a bason, on the S side is a small faint rampire5 of earth with several breaks in it running across the field (at the distance of about 70 feet from the low) from the wall on the W, and across under the wall on wall to the E. N.B., On the W side of the western wall we could find no traces of this rampire, nor any place where it turned. This rampire crossing the Eastern wall as was said before passes quite to the foot of the great rampire of the temple."

Note 1. Mr Manders evidently had the compass bearings on the plan referred to in this MS., wrong. The entrances of the circle are nearly due north and south, and the tumulus is on the south-east.

Note 2. Gib Hill [Map], but its actual distance from the circle is about 300 yds. It is constantly stated by the older writers that this tumulus was connected with the circle by a "rampire." This, however, upon leaving the latter, does not point to Gib Hill [Map], but has a southerly course for about 200 yards, after which it curves to the west, but with a bearing considerably south of the latter, and is then lost. The recent excavations proved that it consists of a small bank and ditch.

Note 3. This tumulus is on the sonth-east.

Note 4. Gib Hill [Map],

Note 5. From personal observations, this is very doubtful (J.W.).

Archaeologia Volume 7 Section XIII. The first low [Gib Hill Barrow [Map]] is on your right hand, if you are travelling southward. It is a large mount of earth, nearly round, of about eighteen feet diameter at the top, where there is a great hollow in the middle, in form of a bason, as is commonp. It is twenty-two yards diameter at the base. The original height to the top five yards two feet height on June 17, 1782, before it was opened three yards two feet. On the south side there is a low rampire of earth with several breaks in it, running across the field (at the distance of about seventy yards from the low) from the wall on the west, and under the wall on the east. These walls are plainly of modern erection; and whereas on the west side of that western wall no traces of the rampire are to be found, nor any place where it turned and being but an insignificant thing, it probably is of a late date too. However, it passes quite to the foot of that great rampire which environs the temple, N° 1. Pl. IX.

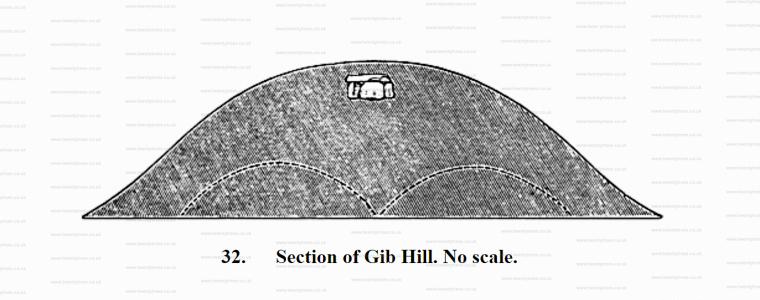

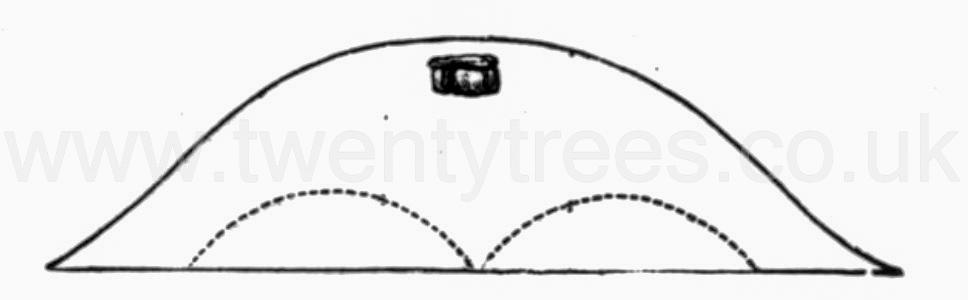

Thomas Bateman 1824. About 350 yards westward from Arbor Lowe [Map] is a barrow of very large size, called Gib Hill [Map], which is connected with the temple of Arbor Lowe by a considerable rampart of earth, now, however, faint and broken, which runs in a serpentine direction towards this barrow, having its commencement at the foot of the vallum of the temple, near the southern entrance. This tumulus is very conical, and rises to the height of about eighteen feet, and has the usual basin-like concavity on its summit. Its height, immense size, and remote antiquity are calculated to impress the reflecting mind with feelings of wonder and admiration. On opening this barrow it was found to consist of earth and limestone, divided by layers of amygdaloid, and in the centre a bed of very stiff reddish-brown clay, completely saturated with what was supposed to be animal matter, most probably arising from the decomposition of human bones. This bed or stratum of clay was laid upon the natural surface, to the depth of about a yard and a half; it was about three yards in diameter, and about five yards from the summit of the mount; this clay was intermixed with a considerable quantity of charcoal and burnt human bones, and a small sprinkling of rats' bones. From it were taken an arrow-head of flint, two and a half inches long, and unburnt, and a fragment of a basaltic celt.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. [Fol. 43.] June 1st and 2nd 18241.

The large barrow [Gib Hill Barrow [Map]] situate 4 or 500 yds. from Arborlow, in a field called Gib hill [Map], belonging to Mr. Thos. Bateman of Middleton by Youlgreave, was opened by Mr W. Bateman (age 37), and myself, by driving a level through the S.E. side to the centre. The first covering which was about 2 yard in depth consisted of loose stones and earth, (but not so stoney as the Arborlow) under which a thin layer of tuft stone. Beneath this was a stratum similar to the first of about 1½ yards in thickness with a second thin bed of tuft stone. To this succeeded a stiff reddish brown clay, completely saturated with what we supposed to be animal matter, and having evident marks of fire. This clay was laid on the natural soil, about 1½ yds. in thickness, and 3 or 4 yards in diameter, and was throughout its whole circumference full of burnt bones and charcoal, disposed apparently in layers. A stratum of tuft stone which we supposed had been changed into a yellow ochry substance by the action of the fire, was placed under this; beneath which we penetrated to the solid rock 5 or 6 yds. in perpendicular height from the summit of the mount. We carefully examined the clayey stratum but could find no traces of an urn having ever been deposited; we found in the clay a small arrow head of flint, and a stone of somewhat peculiar shape, much broken, which might have been made use of as a hatchet2, some pieces of burnt bones (whether human or not cannot be ascertained) and a (very) few bones of rats were found3.

The mount has, no doubt, been raised over the funeral pile of some family, in which the bodies were entirely consumed, perhaps before the introduction of urn burial. The tumulus has evidently been connected with the adjoining temple by a small rampire of earth which runs Southward from the vallum of the Arborlow, round this barrow to the Westward; but may not be coeval with the original foundation of the temple. The remains found are in the possession of Mr. W. Bateman of Middleton.

One of the men employed in this excavation stated positively that he and a John Broomhead, had, under the direction of Mr. B. Thornhill, of Stanton, dug down into the centre of this barrow many years before, when they found the bones of a human hand, and several Coins, some of which were silver, and that on their arrival at some large stones, they desisted. The coins were taken away by Mr. Thornhill. The stones appear to have been considerably above the stratum of burnt bones, &c. mentioned. On Mr. Bateman's application to Mr. Thornhill on the subject, he denied having any recollection of opening the barrow at all.

Samuel Mitchell (age 21) Junior.

Note 1. Vestiges, pp. 31-2, and briefly in Ten Years' Diggings, pp. 17-20, in both of which the above exploration is attributed to Mr. W. Bateman only. These pages in Ten Years' Diggings record the opening of this great-barrow by Mr T. Bateman, January 10th-17th, 1848, when a huge cist containing burnt human bones and a vase were found near the summit.

Note 2. "A battered celt of basaltic stone"- Ten Years' Diggings, p. 20. In addition to the "finds" enumerated above, a small iron fibula was found in the upper part of the mound.

Note 3. Mr. Mitchell's account of the opening of this barrow is valuable, as his description of the construction is more detailed antl explicit than that of Vestiges, p. 31. The exploration of 1848 proved that the upper portion of the mound had been raised over four small ones of clay, placed square-wise. The present writer has recently suggested that these may simply represent the mode of constructing a square mound like that near the south-west side of the great circle at Dove Holes [Map], and that the upper material of stones and earth represents a subsequent enlarging of the barrow when the cist was introduced (Reliquary, 1908). Derbyshire has supplied other examples of barrows which have been raised or otherwise enlarged upon the occasion of later burials.

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. [Fol. 45.] July 1824.

Saw Mr White Watson at Bakewell. He had submitted a portion of the reddish brown clay found in Gib Hill barrow [Map], which I had brought away with me, to Sir Francis Darwin and Dr Booth, who both agreed that the appearances of decayed matter throughout the mass were not sufficiently decisive to warrant the conclusion that they were the effects of decayed animal matter.

Mr Watson thought that the stone somewhat shaped like a hatchet found in Gib Hill Barrow [Map], much broken, was, on comparison with such a like in his possession, the remnant of a Celt of porphyry.

Section II Circles. About a quarter of a mile from Arbor Lowe, in a westerly direction, is a large conical tumulus, known as Gib Hill [Map], which is connected with the vallum of the temple, by a rampire of earth, running in a serpentine direction, not dissimilar to the avenue through the celebrated temple of Abury; to any believer in the serpent worship of the Celtic tribes this fact will be of interest.

There is also a small barrow situated about fifty yards from the south entrance, which has been opened at some period, of which no record remains, which is much to be regretted, as the contents might possibly have thrown some light upon the age of the temple.

Ten Years' Digging 1848. The large barrow upon Middleton Moor, called Gib Hill [Map], situated about 350 yards west from the circular temple of Arborlow [Map], and connected with it by a serpentine ridge of earth, had been previously examined by the late Mr. William Bateman, in 1824, without much success. From the analogy borne by Arborlow and its satellite, Gib Hill, to the plan of Abury with its avenue of stones terminating in a lesser circle on the Hak Pen range of hills, no less than by the remarkable similarity of the names, I had ever reckoned this tumulus to be of more than common importance, under the supposition that a successful excavation of it might yield some approximate data respecting the obscure period of the foundation of the neighbouring circle.

Owing to the large size of the mound, our operations extended over several days, the result of each being noticed diary-wise as at once the most simple and intelligible arrangement.

Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume 16 Page 101. and in the large tumulus called Gib Hill [Map], a cist was discovered, consisting of a slab placed on upright stones; both which are in Mr. Bateman's valuable collection at Youlgrave. (See vol. xv, p. 152, pi. 12, of this Journal, 1859.)

Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume 16 Page 101. Here the advocates of the ophite [serpent] theory see in the wall, or dyke of stone and earth, which runs from the western side of the agger, near the southern entrance, the form of the wished-for serpent, and connect it by a proper curve with a large barrow or tumulus, called Gib Hill [Map], standing about three hundred paces to the westward, which is conveniently made into the reptile's head; but as the dyke heedlessly continues its course even beyond the line of the tumulus, and there terminates in some broken stones, it plainly shews that it has no connexion whatever with the tumulus, or supposed serpent's head, — if, indeed, the dyke is of equal antiquity with it.

Note 1. Called Arbe or Arbor Low. Lowe or low, a Saxon word signifying a hill or mound, is the law of Northumberland. (See plan.)

Note 2. Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire.

Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter IV. Attached to Arbor Low, at a distance of about 250 yards, is another tumulus, called Gib Hill [Map], apparently about 70 to 80 feet in diameter168. It was carefully excavated by Mr. T. Bateman in 1848; but after tunnelling through and through it in every direction on the ground level and finding nothing, he was surprised at finding, on removing the timber which supported his galleries, that the side of the hill fell in, and disclosed the cist very near the summit. The whole fell down, and the stones composing the cist were removed and re-erected in the garden of Lumberdale House. It consisted of four massive blocks of limestone forming the sides of a chamber, 2 feet by 2 feet 6 inches, and covered by one 4 feet square. The cap stone was not more than 18 inches below the turf. By the sudden fall of the side a very pretty vase was crushed, the fragments mingling with the burnt bones it contained; but though restored, unfortunately no representation has been given. The only other articles found in this tumulus were "a battered celt of basaltic stone, a dart or javelin-point of flint, and a small iron fibula, which had been enriched with precious stones."

Note 168. These dimensions are taken from Sir Gardner Wilkinson's plan. The Batemans, with all their merits, are singularly careless in quoting dimensions.

Note 169. Ante, p. 11.

John Lubbock 1879. About a quarter of a mile to the west, there is a large conical tumulus, known as Gib Hill [Map], which was connected with Arbor Low by a rampart of earth, which, however, is now very faint and imperfect. Gib Hill was opened: by Mr. Bateman in 1848. He found that it had been raised over four smaller mounds, consisting of hardened clay mixed with wood and charcoal. The central interment consisted of a dolmen, or stone chamber, situated near the top of the mound. It was composed of four massive limestone blocks covered by a fifth, about four feet square by ten inches in thickness. The cist, having fallen in, was removed, and re-erected in the garden at Lomberdale House [Map]. It contained only a small urn, four-and-a-quarter inches in height, a piece of white flint, and burnt human bones. In the earth of the tumulus were found also a flint arrow-head, a fragment of a basaltic celt, a small iron brooch, and another fragment of iron, supposed by Mr. Bateman to have belonged to a later interment, which had been previously disturbed. To the west, is the Roman Road from Buxton, which passes southwards, not far from Kenslow Top [Map] to the great tumulus of Minning Low [Map].

Harold Gray 1902. On the south-east vallum a, Bronze Age tumulus [Map] was constructed undoubtedly from material derived from the original monument of Arbor Low. As previously stated, no bronze was found here or in Gib Hill [Map], just over 1,000 feet distant; but their other contents point to a Bronze Age culture, probably not particularly late. If the "finds" from this tumulus1 on the vallum of Arbor Low are to be regarded as belonging to the Early Bronze period, "then," as Mr. Henry Balfour said at Belfast, "the probability of the circle being of Neolithic date is much increased."

Note 1. The absence of bronze in this interment does not necessarily give an Early Bronze Age date for the burial, for bronze was rarely found with interments even in the fully-developed Bronze Age. The two pots found in the tumulus (figs. 1 and 2) are not "beakers," or drinking-vessels, which the Hon. John Abercromby has recently classified as being the oldest Bronze Age ceramic type in Britain, Journal of the Anthrolologieal Institute, xxxii. 373.)

Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 30 1908 Page 155. In the adjoining close S. is another barrow and the name Gib hill [Map] given to the close is for that a man was hung on a gibbet there fixt for a murder there committed — Llewing low (a Welch word) is the name of this barrow, other lows there are, Coving low, and Kenslow.

Blacks Guide to Derbyshire. Parsley Hay, where, on getting out of the train, one sees hardly any houses but the forlorn little terminus, and must turn up the road for a modest refreshment room, is also the station for Arbor Low [Map], the Derbyshire Stonehenge, that stands conspicuously elevated a mile to the east on the south of the Bakewell Road. Its Druidical circle, which comes next in importance to those of Stonehenge and Avebury, consists of overthrown stones, mostly 6 to 8 feet high, lying disordered on a platform about 50 yards in diameter, surrounded by a wide ditch. On the east side of the south entrance is a large barrow, the exploration of which has proved the antiquity of this "high place." Some quarter of a mile westwards is another conical tumulus known as Gib Hill [Map], connected with Arbor Low by a bank of earth. On this side the Roman road can be traced, taking its straighter line near the modem turnpike, with which it in part coincides.

Only the present remoteness of Arbor Low prevents it from being more often visited. "Its situation, though considerably elevated, is not so high as some eminences in the neighbouring country; yet it commands an extensive view, especially towards the north-east, in which direction the dreary and sombre wastes of the heath-clad East Moor are perfectly visible, though distant about 15 miles; were it not for a few stone fences, which intervene in the foreground, the solitude of the place and the boundless view of an uncultivated country are such as almost carry the observer back through a multitude of centuries, and make him believe that he sees the same view, and the same state of things as existed in the days of the architects of this once holy fane." — Bateman's Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire.

Harold Gray 1902. The vallum is joined on the south-west by a slightly raised bank about 1½ foot.(45.7 cm.) high, and an almost imperceptible "silted-up" ditch, which run for some distance in a southerly direction, and about which there have been various theories. Some writers have connected this so-called "serpent", with Gib Hill [Map], a tumulus at a distance of 1,043 feet (318 m.1) from the centre of Arbor Low (plate I.). Gib Hill [Map] was unsuccessfully dug into about 1812, and again by William Bateman in 18242, when a few stone implements appear to have been found. In January, 1848, Thomas Bateman made a more thorough examination of the mound, when he discovered a cist, the top stone of which was only 18 inches (45.7 m.) from the apex of the tumulus, containing a cremated interment in a small urn of Bronze Age type3.

Note 1. According to my tape measurement.

Note 2. Bateman's Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire, 31. [Map]