The Life, Letters and Work of Frederic Leighton by Mrs Russell Barrington Volume 2 Chapter V

The Life, Letters and Work of Frederic Leighton by Mrs Russell Barrington Volume 2 Chapter V is in The Life, Letters and Work of Frederic Leighton by Mrs Russell Barrington Volume 2.

Chapter V. Leighton As President Of The Royal Academy 1878-1896

Leighton was at Lerici in the autumn of 1878, visiting his dear old friend Giovanni Costa ("an artist in a hundred—a man in ten thousand," were Leighton's words describing him), when he received a telegram stating that Sir Francis Grant was dead. "The President is dead! Long live the President!" exclaimed Costa. Leighton remained in Italy, sketching landscapes and painting heads—one, the portrait of Costa—till his holiday was over, the end of October. On the 18th of November he was elected President of the Royal Academy. Thirty-five Academicians voted for Leighton, five for Mr. Horsley.

Leighton wrote to his younger sister:—

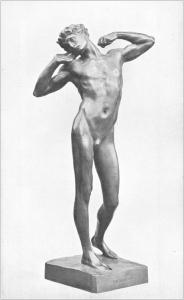

Dearest Gussy,—You perhaps have heard from Lina that I had an overwhelming majority, and that the outer world beyond artistic has warmly received my election, which is of course infinitely gratifying, but fills me with a dread of disappointing everybody. Monday I go to Windsor to be knighted. Yes, I got a first-class gold medal for my statue[58]—at least, it was awarded, and I shall get it some time. I also don't mind telling you in strict confidence—because it is not yet a fait accompli—that I am, I believe, to have the "ruban" of an Officier de la Légion d'Honneur. I am so glad, dear, your wrists are better—may they keep so. Love to old Joseph (Joseph Joachim) when you see him.

Note 58. "Athlete Strangling a Python," exhibited in the International Exhibition, Paris, 1878.

Most treasured of all congratulations were doubtless these lines from his beloved master, Steinle:—

Translation.

Frankfurt am Main, December 1, 1878.

Dear and honoured Friend,—To-day I have read in the paper that the choice of President of the Royal Academy has fallen upon you, and since I am convinced that this distinguished position is both appropriate to your services to art, and also certainly well merited, you must permit an old friend, who remains bound to you in love only, to offer you his dearest and warmest good wishes upon this honour. I pray God, that your position may provide you with great power in your country for good so as to enable you to encourage the noblest things in art. I am convinced that you, dear friend, will make a right and fruitful use of it. I often set my pupils to make enlarged drawings of single groups from your medieval Equipment for the Defence of the Town,[59] and rejoice in the admirable studies which you made for that cartoon. I, dear friend, am in my old age still active and industrious, and would gladly go on learning. Should God grant life, I shall next year complete my work on the Strassburg master, which will demand all my love and strength. Here we have now built a new gallery, on the other side of the river Main, and a new studio. The collections are good, and more suitably accommodated than heretofore, and there is no want of space for future additions. Perhaps one of your journeys will bring you again to the old Main town, and so to the arms of your old friend. My dear President, I repeat my good wishes, and remain with all my heart, your truly devoted,

Edw. Steinle.

Note 59. "The Arts of War."

From his birthplace Leighton received the following announcement:—

BOROUGH OF SCARBOROUGH.

At a meeting of the Council of the Borough of Scarborough, in the County of York, held in the Town Hall in the said Borough, on Monday the ninth day of December, 1878,—

Present,—The Mayor (W.C. Land, Esq.) in the chair,—

It was moved by the Mayor, seconded by Alderman Woodall, and resolved unanimously: "That this Council learns with peculiar satisfaction and pleasure of the election of a native of Scarborough, in the person of Sir Frederic Leighton, to the Presidency of the Royal Academy, and respectfully offers to Sir Frederic its warm congratulations, and records its conviction that his great talents as an artist, his attainments as a scholar, and his many striking qualifications, eminently fit him to adorn the high position to which he has been called."

W.C. Land, Mayor.

Robert Browning wrote:-

19 Warwick Crescent, W., November 14, 1878.

Dear Leighton,—I wish you joy with all my heart, and congratulate us all on your election. There ought to have been no sort of doubt as to the result, but the best of us are misconceived sometimes, though in your case never was a right more incontestable. All I hope is that your new duties will in no way interfere with the practice of your Art. I only venture to write, now, as one who, so many a year ago, saw your beginning with "Cimabue," and from that time to this remained confident what your career would be. But you know all this, and it requires no answer, being rather a spurt of satisfaction at my own original discernment than any assurance which I can fancy you need from,—Yours very truly,

Robert Browning.

Pen's letter to me, two days since, contained his earnest wishes for what has just happened, and he will be delighted accordingly.

From Matthew Arnold:—

Athenæum Club, Pall Mall, S.W.,

November 15.

My dear Leighton,—One line (which you need not answer) to say how delighted I am to see what an excellent choice the Royal Academy has made.

I only hope poor O'Conor may not take advantage of the occasion to plant an ode and a letter.—Ever sincerely yours,

Matthew Arnold.

From Hubert Herkomer:—

November 27, 1878.

My dear Sir Frederic Leighton,—I am just recovering from an attack of brain fever, and although I am not allowed yet to write, I can no longer wait without dictating a letter to express my own individual pleasure at your being the new President.

Three years ago you wrote me a letter after seeing my "Chelsea Pensioners." Perhaps you little dreamt of the tears of joy that that letter caused in a young painter, who will always feel that he owes you a debt of gratitude; and now he glories in your being the chief of that body which attracts to it all the principal art of the country. All England feels that you, from your new position, will give new life to it. Perhaps you will allow me, when I am sufficiently recovered, to come and see you.

In the meantime believe me to be, with most heartfelt congratulations,—Sincerely yours,

A.H., pro Hubert Herkomer.

A friend writes:—

November 15.

Dear Mr. Leighton,—I have tried to keep silence, telling myself that it cannot matter what I think or feel on the subject (and that it may seem to you a very unnecessary proceeding!); but I cannot resist the temptation to tell you how warmly I rejoice, and how earnestly I congratulate myself and all other hungerers after wholesome beauty of colour and form, and high ideals of greatness and purity, on your acceptance of a position that one may hope will, nay must, influence the Art of this time for good in every sense. One takes a great breath of relief as one thinks of it!

Were I to describe to you the effect your works produce on me, and the feeling of real reverence I have for them, I should appear to exaggerate, and should certainly bore you, so I will say no more! and I am not given to that sort of thing.

My beloved Lady Waterford was much disappointed that you could not come and meet her; I need not say, so were we: it was a great enjoyment to have her, she is like no one else; and I yet hope you may come and meet here some day. Pray do not answer this; of course you are overwhelmed with business, and it would hurt me to have it considered and acknowledged as a complimentary civility! whereas it is nothing but an involuntary overflowing to relieve my mind.

From Lord Coleridge:—

1 Sussex Square, W.,

November 24, 1878.

My dear Leighton,—Let me add one voice more, small but true, to the great chorus of applause with which your election has been greeted. It might seem left-handed praise to say that your election was the only possible one; but it is very true praise to say it was the only possible one if the highest interests of English Art, and of the Academy itself, were the sole object of the electors.

It would have pleased and touched you to hear old Boxall speak of it. I dined with him alone on Friday, and he was just and generous, as he always is, in his appreciation of you, and looked forward to your reign as likely to be one of high aims and noble motives. It is a small thing to say, but I venture to agree with him.—Ever sincerely yours,

Coleridge.

These are a few among many hundred congratulatory letters Leighton received on his election. One from Mrs. Fanny Kemble he answered in the following March, when already he was beset by requests to use his influence to get friends' friends' work hung on the walls of the Academy:—

March 20, 1879.

Dear Mrs. Kemble,—Many thanks for your very amiable words of congratulations on the honour done me by the Royal Academy. The kind sympathy shown towards me by my friends had added very greatly indeed to the pleasure my election gave me. The belief entertained by Miss —— that the admission of works to an exhibition is a simple matter of personal favour, is shared by all foreigners—and I fear by many English people—and places me at this time of year in much and often painful embarrassment. So robust is this belief, that those who, having applied to me, fail to find their works on our walls ascribe their absence to personal unfriendliness or discourtesy on my part, or, to say the least, to lukewarmness. As a matter of fact each work of art is admitted or rejected by a separate vote of the Council, and that in complete ignorance (except where authorship saute aux yeux) of the artist's name. This applies equally to English painters and foreign artists who reside here. In regard, however, to foreigners sending from abroad, whilst the vote is taken in the same way, admission is much more difficult. We have so many Anglo-foreign painters who live amongst us that, our Exhibition not being international, we can only admit a very limited number of really prize works. These works are therefore brought before us separately, and a small number of them selected, according to the space we have to deal with; I myself as a rule dissuade my foreign friends from sending except in cases where their merit is really very great; this may be Miss —— case; you will best know. I am quite sure, my dear Mrs. Kemble, that you do not doubt the pleasure it would give me to serve you in the person of your friend, and will not misinterpret these lengthy explanations.

And now I have a favour to ask of you. On Wednesday the 26th, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, Joe will, I hope, play at my studio, and with him Miss Janotha and Piatti; Henschel will, I hope, sing. Will you give me the great pleasure of seeing you amongst my friends on that occasion?—Believe me always, yours very truly,

Fred Leighton.

On December 10, 1879, Leighton delivered his first address to the students of the Royal Academy—one of the finest of the many fine achievements of Leighton's life. "Purely practical and technical matters" he put aside to look into a wider and deeper question, that of the position of Art in its relation to the world at large in the present and in the past time, in order to gather something of its prospects in the future. If the question why Leighton held indisputably the great position he did were asked me by one who for a first time had heard his name, I should be inclined to answer, "Because he contained within him the combined powers to execute completely the art which he created, and to think out and feel such profound, sympathetic, and wise truths as those to be found in this address."[60]

Note 60. "Addresses delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy by the late Lord Leighton." Publishers: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. 1897.

Among the large number of appreciative letters Leighton received were the following.

Millais wrote:—

2 Palace Gate, Kensington, December 11, 1879.

Dear Leighton,—I was suffering all yesterday with tooth-ache, otherwise I would have attended the distribution last night. The ceremony is always most interesting to me, awakening as it does many anxious and happy recollections. My object in writing to you is to say I have read your address, which I think so beautiful, true, and useful that I cannot but obey an impulse of congratulating you upon it. For some time past I have been putting down notes on Art which some day may be put into form, and I find we are thinking precisely in the same way. I have used identical words in what I have written to those you delivered yesterday.

The exponents of Art surround it in such a cloud of mystery that it is a real gain when a practical authority is able to say something definite and clear the way.—Yours sincerely,

J.E. Millais.

His poet-friend wrote:—

Woodberrie, Loughton, Essex, December 11, 1883.

My dear Sir Frederic,—Have any of the multitude of men who love you ever called you Chrysostom? It seems so natural after reading yesterday's address. Will it be published by itself and obtainable in some handier form than the broadsheet of the Times? I want it as part of the education of my daughter, who now, at sixteen, is beginning to take a new interest in whatsoever things are lovely and of good report, and I want it for myself, for in its lovely suggestiveness and exquisite English I could often find refreshment when I wanted (and needed) to "travel in the realms of gold," and forget my own invalided personality under the magic of such guidance.

My wife desires me to say a word of gracious remembrance to you, and I am ever, faithfully yours,

Robin Allen.

Mr. Briton Rivière:

Flaxley, 82 Finchley Road, N.W., December 11, 1879.

Dear Sir Frederic,—After hearing your admirable address last night, I came home in despair, for what little basis of thought is contained in my lectures (more especially in the second one) is built chiefly upon two or three of the lines of argument that you have already expressed so beautifully: Sincerity in the student—The effect of his own time upon him—That time in its relation to the time of the Old Masters, and the temper of mind in which the Old Masters should be studied; on these points my lectures are but a feeble echo of what I heard last night.

My first thought was to change my whole line of battle, and re-write them, but the extreme limitation of my powers of work would make this too great a sacrifice. To throw them up altogether, which I should much like, is impossible, for I am pledged to the Academy to do my best.

Clearly, I must go on, but I shall do so more easily now that I have explained my position, so that if any one who hears me should tell you that my lectures were only a parody of what you had already said so well, you will believe that it has been the misfortune and not the fault of yours very truly,

Briton Rivière.

Don't trouble to answer this.

Matthew Arnold:—

Athenæum Club, Pall Mall, April 19, 1880.

My dear Leighton,—You have been better than your word, for I see you have made me the actual possessor of your "address." From the glance I have already taken at it, I see that I shall both like it and you with it; but of this I might have been sure beforehand. A thousand thanks, and believe me, always sincerely yours,

Matthew Arnold.

The scheme Leighton formed, when first considering the duty among all others he undertook,[61] of addressing the students at the biennial meetings, was begun and continued in the nine addresses he gave, but unfortunately it could not be completed, a fact he sorely regretted when discussing the question with me three months before his death. On December 10, 1879, "The position of Art in the World" was the subject. In 1881, "Relation of Art to Time, Place, and Racial Conditions; Underlying Mystery of its Growth and Decay." In 1885, "Summary of Foregoing Lecture." In 1887, "Art in Mediæval and Modern Italy." In 1889, "Relation of Artistic Production to Surrounding Conditions considered in reference to Spain." In 1891, "The Art of France: its uninterrupted development; its wide field; eminent achievement in Architecture; the Gothic style." In 1893, "The Art of Germany: its high qualities; deficient Æsthetic Inspiration." The tenth was to have consisted, Leighton told me, in a summing up of the nine former addresses, in order to prove how they had affected the past and present condition of Art in England. To any thoughtful artist these utterances, delivered by so great and accomplished an authority, cannot fail to prove profoundly interesting and invaluable as references, on account of the sound knowledge and the absolutely reliable quality of the facts given; but it may be doubted whether the more informative matter, contained in the six later lectures, suited Leighton's style of oratory so happily as did the more abstract quality of the three first. There appeared to be too many names crowded into the comparatively short time which Leighton allotted to himself for the delivery of these discourses, for the normal taking-in power of an audience; the very finished rhetoric, moreover, in which the enormous amount of information contained in each was disclosed, did not seem quite appropriate to their condensed form. In conversation I have heard Leighton far more convincing, on the same subjects as those he treated in the last six discourses. The same intense sense of the duty he felt to do the thing as completely as it was possible, which he evinced in painting, cropped up again in his oratory, no less than the intense modesty—which would not recognise how great he could be if he relaxed all effort, and was simply himself.

Note 61. "Not everybody," wrote the late Mr. Underhill, who for some time, as private secretary to Sir Frederic Leighton, had special opportunities of knowing, "is aware of the tax upon a man's time and energy that is involved in the acceptance of the office in question. The post is a peculiar one, and requires a combination of talents not frequently to be found, inasmuch as it demands an established standing as a painter, together with great urbanity and considerable social position. The inroads which the occupancy of the office makes upon an artist's time are very considerable. There is, on the average, at least one Council meeting for every three weeks throughout the whole year. There are, from time to time, general assemblies for the election of new members and for other purposes, over which the President is bound, of course, to preside. For ten days or a fortnight in every April he has to be in attendance with the Council daily at Burlington House, for the purpose of selecting the pictures which are to be hung in the Spring Exhibition. He has to preside over the banquet which yearly precedes the opening of the Academy, and he has to act as host at the annual conversazione. Finally, it is his duty every other year to deliver a long, elaborate, and carefully prepared 'Discourse' upon matters connected with art, to the students who are for that purpose assembled. It is a post of much honour and small profit." "To administer the affairs of the Academy, to fulfil a round of social semi-public and public engagements, and to paint pictures which invariably reach a high level of excellence, would, of course, be impossible—even to Sir Frederic Leighton—were it not for the fact that he makes the very most of the time at his disposal. 'That's the secret,' remarked a distinguished member of the Academy to the present writer some little time before the President's death; 'Sir Frederic knows exactly how long it will take to do a certain thing, and he apportions his time accordingly.'"—"Frederic, Lord Leighton, P.R.A.: His Life and Works." By Ernest Rhys.

Mr. Briton Rivière, in the notes he furnishes for this book, writes:—

"Those perhaps sometimes too perfectly built-up sentences, of which his admirable addresses and speeches were formed, were the outcome of this same quality of mind. One of his most intimate friends, when we were talking about the mental strain occasioned by these, once said to me: 'Leighton would never get over a slight lapse of grammar,' and I can believe it. The accidental was hateful to him when considered in reference to his own work of any kind, though probably no one knew better than he did its value in a work of art; but, as Watts deplored, he never would use it or admit it into his own pictures. This quality and its strain upon him was illustrated by an accident which occurred at his last R.A. Banquet speech, the last he ever made, and which gained immensely from the fact that in one place he forgot for a moment the next sentence, and came to a pause (as he told me afterwards), in fear that he had broken down altogether; but his suspense, painful as it must have been to him, looked perfectly natural and spontaneous, and gave to his speech that touch of something which his better remembered periods did not express so well. This system of speaking entirely from memory added much to the constant strain of his Academy work. He had what he called a 'topical memory,' viz. he remembered the place of each word in his written speech and used to read it off in the air with never-failing accuracy, but did so always with the belief that a forgotten sentence would shipwreck the whole. If he would have been content now and then to lapse from this high pitch of the accuracy he aimed at in all his work, few could have reached a safer or higher standard spontaneously, as he proved in the Royal Academy, General Assembly, and Council meetings, when he never failed to speak admirably on the spur of the moment; and his summing up of a debate there on any subject was invariably marked by the same elegance and cleverness as his prepared speeches, but with more vitality and flexibility, which, however, never led him into anything that was not almost fastidiously exact and precise. I have always felt that no one who had heard only his elaborately prepared speeches knew his real power as a speaker."

Throughout their pages are to be found most suggestive passages, inspiring new thoughts and, to any but experts, new facts on vitally interesting art matters. For instance, take the description of Velasquez:—

"For a long period Italian painting did not cease to enjoy the favour of the Court; it ceased, however, towards the beginning of the seventeenth century to exercise that paralysing influence which had marked its first advent, and the ground was cleared for a new impulse from within. At this conjuncture a man of commanding genius and fearless initiative was given to Spain in the person of Diego Velasquez. It may perhaps have surprised you that with such a name before my mind I should have spoken of Zurbaran, a man so vastly his inferior in the painter's gift, as perhaps the most representative of Spanish artists. I have done so because beyond any other artist he sums up in himself, as I have pointed out to you, all the complex elements of the Spanish genius. In Velasquez, Spanish as he is to the finger-tips, this comprehensiveness is not found. Of Velasquez all was Spanish, but Zurbaran was all Spain.

"Viewed simply as a painter, the great Sevillian was, as I have just said, vastly the superior of the Estremeño. He was in more intimate touch with Nature, and none, perhaps, have equalled the swift magic of his brush. On the other hand, depth of feeling, poetry, imagination were refused to him. The painter of the 'Lanzas,' the 'Hilanderas,' the 'Meninas'—works in their kind unapproached in Art by any other man—painted also, be it remembered, the 'Coronation of the Virgin' and the 'Mars' of the Madrid Gallery—types of prosaic treatment. In one work, indeed, Religion seems for a moment to have winged his pencil; but striking and pathetic as is his famous 'Crucifixion,' it does not equal in poignancy and imaginative grasp the presentment of the same subject by Zurbaran in Seville. But if we miss in Velasquez the higher gifts of the imagination, we find him also free from all those blemishes of extravagance which we have so often noted in this land of powerful impulses unrestrained by tact. Whatever gifts may have been refused to Velasquez, in his grave simplicity he is unsurpassed. If fancy seldom lifts him above the level of intimate daily things, neither does she obstruct for him with purple wings the white light of sober truth. In days in which the young Herrera could find favour; in a country in which Churriguera was possible, and euphuism was applauded, he never overstepped the modesty of Nature, nor forgot in Art the value of reticent control. I have not here to follow his career, nor the evolution of his unique and dazzling genius. Still less need I, before young artists of the present day, dwell on the wizardry and the luscious fascination of the brush of this most modern of the old masters. I will only, in conclusion, touch briefly on one or two points that are of interest, and one that is, perhaps, of warning.

"First, I would notice the purity and decorum of his art; a decorum not, I think, due to the characteristically Spanish laws under which the Inquisition visited with heavy penalties every semblance even of impurity in a work of art, but to a spirit dwelling in the people itself, of which those laws were but the somewhat exaggerated expression. It may be worth while also to note that yet another virtue of the Spaniards is, in one of his works, reflected in an unexpected manner, namely, their sobriety. It is a curious thing that in a certain class of Spanish literature a peculiar relish is shown for the portraying of moral squalor and the grovelling criminality of social outcasts. In Spanish Art, on the other hand, the picturesqueness alone of low life seems to have sought expression. You know what gentle Murillo made of his melon-eating beggar boys. Again, you saw not long ago upon these walls, in the 'Water-Carrier of Seville,' how at the outset of his career Velasquez turned his thoughts to subjects drawn from humble life, and you know how to the end he dwelt with peculiar gusto on the fantastic physiognomy of the privileged buffoons, dwarfs, and hombres de placer who haunted the Palace in his day. You know further that one of the most powerful works painted by him before reality of atmospheric effect had become his chief preoccupation, and when he sought exclusively after truth of character, a picture known as 'Los Borrachos,' represents a group of drunkards doing homage to Bacchus. It is a work of the most naked realism. Bacchus (Dionysos!), showing his repulsive vulgarity (what a blank to Velasquez was the poetic side of classic myths), is surrounded by a circle of kneeling rascals, rude and ragged enough, and supposed, no doubt, to be carousing; but here is the strange peculiarity of this work—in spite of all the accessories of a revel, and the flash of grinning teeth, we are unable to persuade ourselves that any one of the disreputable crew could ever be drunk. Imagine the subject treated by a Fleming.

"And now, though I am loth to touch one leaf of the laurels of so dazzling and so great an artist, I cannot pass in silence a circumstance which must be weighed in estimating Velasquez as a man, and which is not without bearing on his art. The virtues of his race, as we have seen, purified his work and gave it dignity; a Spanish foible, though it could not dim his genius, cramped, no doubt, and curtailed its production—namely, a tendency to subordinate everything to the pursuit of royal favour. I said a Spanish foible; for a superstitious rendering up of will and conscience to the sovereign, such as is, I believe, without example, had long been a growing characteristic of the Spaniard. On a memorable occasion Gonzalo de Cordoba himself, one of the noblest figures recorded in Spanish history—a man of a mind so fearless that he was bold to rebuke Pope Borgia himself face to face in the Vatican for the scandals of his life—did not scruple to break, in deference to what he considered this higher duty of obedience to his king, his solemn pledge and oath to the unfortunate young Duke of Calabria. So all but divine did majesty appear to the Spaniards, that divinity and majesty became almost as one in their eyes, and they spoke, in all solemnity, as 'Su Majestad,' not only of the Divine persons of the Trinity, but also of the sacrificial wafer. The prevalence of this feeling must plead to some extent in mitigation of the tenacity with which Velasquez canvassed—with success, alas!—to obtain at Court a post of an onerous and wholly prosaic character—the office of 'Aposentador Mayor,' a sort of purveyor and quartermaster, who, when his Majesty moved from one place to another, had to convey, to house, to feed, not the sovereign only, but all his suite. A post demanding all his attention, says Polomino, who goes on to deplore that this exalted office (which he has just told us any one could fill) should have deprived the world of so many samples of the painter's genius. We shall agree with our sententious friend, not, perhaps, in the satisfaction he derived from the honour conferred, as he imagines, on his calling, but in his sorrow over the loss we have sustained! And in the sight of canvases in which the execution of a sketch is carried out on the full scale of life we shall at once bow before the product of a splendid genius, and regret the signs of haste, the evidence of too scanty leisure, by which its expression has been marred. Truly it has been said, 'Art requires the whole man.'"

Note 62. While writing this discourse Leighton wrote to his father:—

Perugia, October 5, 1889.

Dear Dad,—You will be surprised to hear that your letter (for which best thanks) only came to my hands yesterday on my arrival here; it had apparently, after enjoying a junket through Spain, returned to England before its final despatch here. The envelope, which I enclose, will amuse you; Ulysses himself did not visit more cities of men! I am glad my Spanish tour is at an end; the insufferable heat, the long journeys, the frequent night travelling, have conspired to make it rather trying to me physically. I have never been thoroughly well the whole time. Here it is absolutely cold, and I shall probably soon begin firing; it rains also, and I fear the weather is altogether unpromising; but the air is magnificent, and I am very fond of the place, and I shall enjoy my stay as much as the necessity of writing my (adjective) Address will allow.

My journey through Spain, though fatiguing, was extremely interesting and very profitable to me for the matter in hand. My stay in Madrid was made more enjoyable by the extreme amiability of my very old friend our ambassador, who brought me into contact with two or three interesting people, from whom I gathered valuable information in regard to things Spanish; to say nothing of getting compartments reserved for me in trains, &c. &c. It is rather fortunate that our diplomatic representatives abroad are mostly personal friends of mine. Post is just going, so good-bye for the present.—Your affectionate son,

Fred.

Leighton mastered the Spanish language completely in the course of the few weeks he spent in Spain in 1866. A friend who was present gives an amusing account of an incident which occurred when Leighton dined with Mrs. Adelaide Sartoris after his return. He was sitting next Señor Garcia (only now just dead at the age of 102); the conversation was being carried on in Spanish. Mrs. Sartoris, in astonishment and admiration at the fluent manner in which Leighton was talking the language of which he did not know a word a few weeks before, exclaimed, "But, Señor Garcia, do say he makes some little mistakes!" "But he doesn't," replied Garcia; "he hasn't made one!"

Again, the seventh discourse is replete with inspiring suggestions about French architecture,[63] and in the last discourse the description of Albert Dürer is one which, in a few lines, gives a complete and vividly interesting setting to the great name.

"Albert Dürer may be regarded as par excellence the typical German artist—far more so than his great contemporary Holbein. He was a man of a strong and upright nature, bent on pure and high ideals; a man ever seeking, if I may use his own characteristic expression, to make known through his work the mysterious treasure that was laid up in his heart; he was a thinker, a theorist, and, as you know, a writer; like many of the great artists of the Renaissance, he was steeped also in the love of science. His work was in his own image; it was, like nearly all German art, primarily ethic in its complexion; like all German art it bore traces of foreign influence—drawn, in his case, first from Flanders and later from Italy. In his work, as in all German art, the national character asserted itself above every trammel of external influence. Superbly inexhaustible as a designer, as a draughtsman he was powerful, thorough, and minute to a marvel, but never without a certain almost caligraphic mannerism of hand, wanting in spontaneous simplicity—never broadly serene. In his colour he was rich and vivid, not always unerring as to his harmonies, not alluring in his execution—withal a giant."

Note 63. Mr. Norman Shaw wrote the following letter the day after he heard this address in 1891:—

6 Ellerdale Road, Hampstead, N.W., December 11, 1891.

Dear Sir Frederic,—I was so sorry I missed you last night. After the election I went into the galleries to find my people, and when I came out you had gone—and quite right too, for you must have been very tired.

I thank you very sincerely for your most admirable address. I had heard that it was to be on the subject of French Art, but I had not realised that it was to be entirely about Architecture! and as an architect I naturally feel very deeply its great and permanent value. It is altogether a new sensation to have a Presidential address devoted to the Mother of the Arts! and I am sure its influence will be wide, deep, and lasting.

Amongst the many regrettable phases of modern art, there is none that I feel more than the isolation that the three great branches of art exist under in this country (for in France I am sure it is quite different), and I cannot help feeling that your address is a tremendous step in the right direction; but, alas! I don't believe one in twenty of our colleagues understood what you were so clearly explaining, and I fear not one in fifty cared! But it is absurd to suppose that with the advancement of knowledge this state of things can last, so it is intensely satisfactory to have it on record that not merely have we had a President that knew all that is to be known about the art, but who also cared and loved it!

I thought your remarks on the French apse quite delightful. I have always felt this strongly, and though as an Englishman (Scotchman!) I like our square east ends, still I am bound to admit that there is a logical completeness about a chevet that the square end cannot claim. But I shall only weary you if I go on in this prosy way! so thanking you again most heartily for your grand contribution, believe me to remain,—Yours very sincerely,

R. Norman Shaw.

When the last addresses were given Leighton was getting very tired. The wheels were running down—vitality was waning. The great mental machine had begun to work more mechanically. We trace this in the manner in which he tackled his last discourse. While writing it at Perugia he wrote to his elder sister:—

Perugia, Thursday, October 12, 1893.

You have misconstrued my knee; I have no pain in it, at most occasionally a dull ache in the muscles and a slight soreness in the joint; but it is an incapacitating and depressing nuisance, and it won't move on. (I am writing near a window opening on to a clear, star-bright sky; far below, in the paese, I hear the tinkle of a wandering, nocturnal mandoline—how I like it!) You do me the honour to appreciate my having, during my recent precipitate odyssey, visited thirty towns in thirty days, noting things of which I had already accurate knowledge d'avance; but I can "go one better" than that: ten of the towns were absolutely new to me, and of the whole subject on which I am preaching, I knew as good as nothing when you last saw me. I suspect that, in spite of a lack of memory which baffles belief, I have a certain "uptaking" knack. My preachment will bore you, but you will (if you read it) detect an ensemble; but, for goodness' sake, zitti! They'll think, when they hear the P.R.A., that, Lor' bless him! he'd known it all his life. Nevertheless, enough for the day, &c. Best love to Gussy.—Affect. bro.,

Fred.

I remember—when my husband and I were sitting with him one afternoon after his return home that autumn—his saying, "I feel distinctly I have dropped one step down off of the ladder," and it was truly about that time that his doctor, Doctor Roberts, discerned the beginning of the disease which proved fatal. Already in 1888 he wrote:

"The reasons which have now for a good many years impelled me to decline any 'public utterances' outside Burlington House have increased in weight and force as life and strength wanes, and as demands on me grow in every direction. I am sometimes asked to speak in public, not only in London, but all over the country, and in all cases the demand is grounded on strong claims in so far as I am an 'official' artist. Assent once is assent always—assent in half the cases would mean the gravest injury to my work, and I am a workman first and an official afterwards. Things have their humorous side, for those who press me most are sometimes those who on other occasions most earnestly assure me that I 'do too much.' How tired I am of hearing it."

The speeches at the yearly banquets of the Royal Academy were extraordinary tours de force. Wherever Leighton took the lead—and he was seldom anywhere when he did not take the lead,[64]—he raised the tone of the proceedings, and convinced the outside world, no less than those taking a part in them, that the matter in hand was important and essentially worth doing. Personally I have always felt that the finished form of Leighton's diction tended rather to hide than to explain the real nature of the power which had this vitalising, elevating influence. This influence emanated, I believe, from the greatness of his "magnificent intellect" (to use Watts' words) being united with extraordinary will-force invariably employed in the service of the principles in which he had a profound faith. It was his persistent loyalty to these principles—backed by this abnormal will-force, giving it extra weight—which lifted Leighton's work in all directions on to so distinguished a level—and not—in the case of his speeches—his rounded periods, or his power over words, or his gift of facility in grasping a subject, though the Banquet speeches are also remarkable on account of the versatility he displayed in grasping many subjects from the point of view of the expert. Whether it was the Army, the Navy, Politics, Music—whatever, in fact, was the affair of the moment, he proposed the toast from what might be called the inside of the question, not merely treating his text as a matter of form.[65]

Note 65. From a boy, without any effort or thought on his part, he exercised an unquestioned domination over others. Speaking of the days when he, as a boy of seventeen, first made friends with Leighton in Rome, Sir E. Poynter said, "He knew he was clever, but he hadn't a particle of conceit. I never saw him cast down, he was always jolly and noble; none ever thought of refusing him obedience." Again, Sir E. Poynter refers to these early days in his Dedication to Leighton of "Ten Lectures on Art": "I came to-day from the 'Varnishing Day' at the Royal Academy Exhibition with a pleasant conviction that there is, on all sides, a more decided tendency towards a higher standard in Art, both as regards treatment of subject and execution, than I have before noticed; and I have no hesitation in attributing this sudden improvement, in the main, to the stimulus given us all by the election of our new President, and to the influence of the energy, thoroughness, and nobility of aim which he displays in everything he undertakes. I was probably the first, when we were both young, and in Rome together, to whom he had the opportunity of showing the disinterested kindness which he has invariably extended to beginners; and to him, as the friend and master who first directed my ambition, and whose precepts I never fail to recall when at work (as many another will recall them), I venture to dedicate this book with affection and respect." Signor Giovanni Costa wrote: "I remember once in Siena there was an unemployed half-hour in our programme. Leighton happening to go to the window of the hotel, exclaimed, 'The Cupola of the Duomo is on fire!' and as he said it he rushed downstairs to go there. I, being lame, could not keep pace with him, but followed, and on arriving in the Piazza attempted to enter the Duomo past a line of soldiers who were keeping the ground; but they would not allow me to. Seeing them carrying wooden hoardings into the cathedral, I shouted. 'You are taking fuel to the fire! Let me in—I am an artist and a custodian of artistic treasures.' The word 'custodian' moved them, and they let me pass. When I got inside the Duomo I found Leighton commanding in the midst. He was saying, 'You are bringing fuel to the fire.' There was a major of infantry with his company, who cried out, 'Open the windows!' Leighton exclaimed, 'My dear sir, you are fanning the flames; you must shut the windows.' He had placed himself at the head of everybody, and the windows were shut. From the cupola into the church fell melting flakes of fire ('cadean di fuoco dilatate falde'—Dante) from the burning and liquefied lead, which would certainly have ignited the boards with which they had intended to cover the graffitte by Beccafumi on the marble pavement. Our half-hour was over. Leighton looked at his watch and said, 'In any case the cupola is burnt; let us be off to the Opera del Duomo; Duccio Buoninsegna is waiting for us!'"

Note 65. Sir George Grove wrote after the banquet in 1882: "Dear Leighton,—Let me say a word of most hearty congratulations on the brilliant way in which you got through your Herculean task on Saturday. You are really a prodigy! Your last speech reads just as fresh and gay and unembarrassed as the first, and every one of the nine is as neat, as pointed, as perfectly à propos as if there were nothing else to be said! Thank you especially for the reference to the music business."

On asking Gladstone to the Banquet of 1880, Leighton received the following characteristic answer:—

My dear President,—I have received your letter with mixed feelings. You do me great honour, and I must obey you. But I long for the return of the good old times, lying within the long range of my memory, when the dinners of the Academy did not suffer the contamination of political toasts, and kept us all for three precious hours in purer air. Can you tell me when the practice was changed? I am not, I think, under the dominion of a pleasant delusion.—Yours most faithfully,

W.E. Gladstone.

In 1883 Leighton found it impossible to continue his duties as Lieutenant-Colonel of the 20th Middlesex (Artists) Volunteers, which post he had held since 1876, and he therefore resigned. He was then made Hon. Colonel and holder of the Volunteer Decoration.[66]

Note 66. The following is one of many letters of regret expressed when Leighton resigned:—

19 Queen Street, Mayfair, W., June 24.

Dear Sir Frederic,—I trust you will allow me to express to you the sincere regret I feel at your being compelled to give up your command of the "Artists." To myself volunteering has always been so inseparably connected with your command, that I cannot at present realise the extent of the blank which your resignation will create. I shall ever remember with pride that it was under your auspices that I rose through the ranks and obtained my commission.—Believe me, dear Sir Frederic, very truly yours,

W. Pasteur.

A few years later he made the following speech at a dinner given by his Corps, in response to a toast proposed to himself:—

We live in times so hustling and breathless, times in which so much happens in so short a space, that a few years seem to divide men and habits like a deep gulf, and I feel that in the eyes of many of you the toast that your C.O. has invited you in such friendly terms to drink is one possessing an almost antiquarian flavour interest; the more grateful therefore am I for the cordial response with which, not, I hope, solely in a spirit of discipline, but from a more human point of view, you have given to the call of Colonel Edis.

The sight of the old uniform recalls to me, in a vivid manner, a period when not only my years, but my circumferencial inches, were fewer, during which it was my pride, first in one grade, then successively in others, from the ranks to the command, to take my share in the doings of and the life of what I hope I may call, without egotism, one of the finest corps in the Volunteer service. I have now for some years laid by the coat, to be furbished up only for these annual gatherings, not without misgivings as to my power of getting into it; but I have not laid by, nor shall I lay by while I have life, my deep interest and my high respect for that great defensive force of which it is the sign, and which, having sprung into existence in a moment of emergency and national excitement, has shown through over more than a quarter of a century that it requires no excitement to sustain it, and is fed by no transitory fires.

But whilst I watch this great sign of national vitality with unchanging interest, there is of course an inmost corner of my heart in which that national movement appears to me clad in grey and silver, and the old corps still sits in the warmest place; praise of its performance is always to me the most grateful praise; strictures on its shortcomings, if like other human things it has any, will always find me sensitive, and the account which your excellent Colonel furnishes on these occasions of your year's growth, comes home to me more than other like utterances. Gentlemen, I have named your energetic and efficient commanding officer; there is this year a special reason why his name should be on my lips; he is about shortly to acquire by length of service the full colonelcy of which his long devotion to the cause makes him so worthy a recipient; and I should wish before sitting down to offer him an old comrade's hearty congratulation, and the expression of my confident hope that his advanced rank will only confirm him in his loyal and faithful efforts to promote the honour of the corps to which he, more fortunate than I, is still privileged to belong as an active member.

In 1894, on the occasion of fêting his friend Joseph Joachim and presenting the gift to the great master of a Stradivarius violin and bow from his friends, in recognition of the fiftieth anniversary of his first performance in London, Leighton made the following speech:—

Ladies And Gentlemen,—It was necessary that the motives and feelings which have drawn us together to-night should find brief expression on somebody's lips; and, in obedience to a command which has been laid on me by this Committee, I have to ask you to accept me, for a few moments, as your mouthpiece. Of the varied duties which life lays on us, there are some which we perform in simple discharge of conscience and with little joy; some, if few, into the discharge of which we can pour all our hearts; and such a duty is this which I have risen to perform.

I have said that I shall only ask your attention for a few moments, and you will feel with me the fitness of brevity; for besides that, in every case, taste imposes restraint in praise of those who are present before us, long drawn and redundant eulogy would clash strangely with that rare simplicity which is one of the qualities by which Joachim, the Man, compels the esteem of all whose fortune it is to know him. But there would be in it, I think, also a further deeper-lying incongruity, for we know that Joachim, the Artist, has risen to the heights he occupies, perhaps alone, by fixing his constant gaze on high ideals, and lifting and sustaining his mind in a region above the shifting fickle atmosphere of praise or blame. Well, it is now fifty years since he took his first step along the upward path, which he has trodden in wholeness of heart and singleness of purpose from earliest boyhood to mellow middle age. During these fifty years he has not only ripened to the full his splendid gifts as an interpreter, ever interpreting the noblest works in the noblest manner, leading his hearers to their better comprehension; not only marked his place in the front ranks of living composers by works instinct with fire and imagination; but shown us also, as a man, how much high gifts are enhanced by modesty, and how good a thing to see is the life of an Artist who has never paltered with the dignity of his Art.

Deep appreciation of these titles to respect and admiration has, as you know, led in Germany, the country of his adoption and his home, to an enthusiastic celebration of this, the fiftieth year of his artistic career; and we, his English friends, living in a country which we hope, nay, believe, is, after his own, not the least dear to him, have felt strongly impelled to express to him also in some form our gratitude, our sympathy, and our esteem. It has seemed to your Committee that these sentiments could not take a more fitting outward shape than that of the instrument over which he is lord: such an instrument, signed with the famous name of Stradivarius, and, as I am told, not unworthy of his fame, flanked with a bow the work of Tourte, and once the property of Kiesenwetter—such a fiddle and such a bow I now offer to him in your name. Its sensitive and well-seasoned shell will acknowledge and respond to the hand of the master, and the souls of many great musicians will, we hope, often speak through it to spellbound hearers. But we nourish another hope—the hope that, through the great waves of melody that shall roll forth from it under his compelling bow, a still small voice may now and again be interfused which, reaching his heart through his ears, shall speak to it of the many friends who, in spirit or in the body, are gathered round him affectionately to-night.

In 1888 Leighton delivered the superb Address at the Art Congress held at Liverpool on December 3 (see Appendix). No Life of this great man would be complete were his utterances on this occasion not given in full, for therein is found his creed on Art, and the records of those principles on which it was founded, expounded with clear force, fine analysis, and, above all, with supreme courage. The subject, moreover, as touching England's condition respecting Art, is one directly affecting English readers.

A matter of interest to the general Art world came under discussion at the Council meetings of the Academy in the winter of 1879 and 1880, namely, whether women were to be admitted as members of their body. A correspondence took place between Leighton and the late Mr. Henry Wells, R.A., on the subject. Leighton's personal inclination was certainly for admitting women into the body of the elect, as I know from conversations he had with me on the subject. He invariably sought to extend all art privileges to those who were, as artists, worthy to receive them. He told me, however, that the majority of votes against the inroad of women would be given as having regard to a question of convenience rather than to one of principle, namely, the difficulty the Academicians foresaw in admitting only one or two lady artist Academicians to the yearly Banquets, and the greater difficulty of extending invitations to lady guests.[67]

Note 67. The following correspondence took place between Leighton and Mr. Henry Wells, R.A.

To Sir Frederic Leighton, P.R.A.

January 27, (?) 1880.

I will avail myself of this opportunity to remark upon the statement you made in your summing up, viz. that if women were made members under the existing law they would not have the right to sit on Council.

If you can establish this, if you can show us that any one elected a "member" under our law can be debarred on the score of sex from taking a seat on the Council, then I will instantly allow that our laws do provide for the election of women, and that the very ground of our argument is proved to be a quicksand. When you endorsed the statement that came so naturally from Millais, Calderon, and Leslie, I felt the matter was serious, for I saw at once that you could not do justice to our argument in the summing up because its very foundation was misapprehended by you. Although the question is now disposed of, I beg of you to look closely into the matter and assure yourself of it. I only wish I had known beforehand where your doubts were centered, for I would have done my best to remove them. I know you will find, beyond all doubt and controversy, that any one made a "member" by election can make good a claim to a seat on the Council, just as Mr. Tresham made good his claim; and it is because our laws provide for only one kind of members—a Council-sitting kind—that we felt the necessity of providing for the election of a non-Council-sitting kind.

In making this distinction we follow the example of George the Third and the founders of the Academy (who presumably knew something of the understanding upon which the two ladies became connected with the Society), for their decision, when they administered the law in the Tresham case, excluded women from a privilege which could not be denied to a "member" elected under the law. Of course their and our interpretation is open to dispute; but this much is beyond dispute, that if the law is interpreted as providing for women being "members," then it also places them (against the intention, as we see, of the founders) upon the Council; and as the great majority of the present Academicians have made up their minds that women shall not sit on Council, legislation would be necessary on either reading of the law.

The schedule of privileges to be given on the one hypothesis, would on the other give place to a subtraction of privileges, and either schedule would be determined according to the varying shades of opinions of the members.

There would remain only this difference in the result; one schedule would be based upon a law that is open to varying interpretations, whereas according to our method the schedule was based upon a positive resolution providing for the election of women, thus removing the question from all future discussion and doubt.

H.T.W.

From Sir Frederic Leighton, P.R.A.

January 30, 1880.

"In regard to the women question, I perfectly saw your contention and the logical cohesion of your view, and I was familiar with the Tresham episode, only I dissent from your view; I maintain that there were from the first non-Council-sitting members—for 'members' the women certainly were. 'It is the King's pleasure that the following forty persons be the original members of the Society,' and they did not serve on Council, as the roster shows, though all members were supposed to have sat; of course the laws were for the original as well as the elected members, and if the privilege could be refused to an original member whose name stands on the paper that says that all members shall serve in Council, it can and must on the same grounds be refused to elected female members after the custom is consecrated by Royal sanction."

January 31, 1880.

"Dear Wells,—I should much like to hear what you wish to say about the office of Treasurer—there are several points connected directly or indirectly with the office which it will be well to consider before I ask the Queen to appoint, and I have called a Council for Thursday (the funeral is not till Tuesday), at which these matters may be considered. It would seem advisable and convenient that the Treasurer's work be done at the Academy, and not away from it. I think also that the wording of the clause appointing a Surveyor might be made clearer; it ought not to be possible for any one to misunderstand or misinterpret its bearing. Unfortunately I have an appointment to-morrow afternoon at 4.30, and my work in the day is so urgent, having to be handed over on a fixed day, that I cannot leave it—would Tuesday at five do? say at the Athenæum, or here a little later? we should still be forty-eight hours in advance of the Council. In regard to the women question, I perfectly saw your contention and the logical cohesion of your view, and I was familiar with the Tresham episode, only I dissent from your view; I maintain that there were from the first 'non-Council-sitting' members—for 'members' the women certainly were: 'It is Her Majesty's pleasure that the following forty persons be the original members of the Society,' and they did not serve on Council as the roster shows, though all members were supposed to have sat. Of course the laws were for the 'original' as well as for the 'elected' members, and if the privilege could be refused to an original member whose name stands on the paper, that says that all members shall serve on Council, it can and must on the same grounds be refused to 'elected' female members after the custom is consecrated by Royal sanction.—In haste, yours very truly,

Fred Leighton.

"I have said nothing in this letter about poor Barry, but you may imagine whether the tragic event has moved and haunts me."

To Sir Frederic Leighton, P.R.A.

February 1, 1880.

I am very glad indeed to have the statement of your views which you have given me on the women question. Everything is now clear, side matters are disposed of, and only a single point remains on which we have to join issue. On my part I hold that our laws are in a definite and unequivocal form. That their foundation is in the "Instrument" and that every addition to, or modification, or annulment of the provisions in that document has been made in the manner prescribed, viz. by "resolutions" passed by the General Assembly and afterwards sanctioned by the Sovereign. These acts of legislation are all drawn up in a special way (as to size and pattern), to receive the sign manual of the Sovereign; and the tablets arranged in the order of their dates constitute our Statute-Book. I hold that no law can be changed or privilege taken away except by a subsequent act of legislation done in the prescribed manner.

On your part you hold that laws can be changed and privileges taken away by a "custom consecrated by Royal sanction." Thus the issue raised is very clear and distinct indeed.

I will point out that the question as to women sitting on Council was only on one occasion, and then only incidentally, before the Academy. Until the Tresham case arose the ballot had been used in forming the Council, and consequently no question of rights could appear while that process remained unchallenged. But whether we are discussing a single act of adjudication, or such a succession of acts as may be called a "custom," is really immaterial, because the sole question before us is this—can any act or acts other than those of legislation override and supplant the enactments of our law?

If it could be established that our laws must give way to the class of acts you point to, it would then be the first duty of the Academy to have our records minutely searched to ascertain what other laws have been supplanted by administrative actions sanctioned by the Sovereign; and the historical method so much discountenanced at our last Assembly would in truth rise into paramount importance. Many cases would most probably be found. We have one in suspense before us at this moment—the case of the engravers.

The laws of the Academy distinctly provide (but not more distinctly than that without discrimination "members" shall sit on Council) that a vacancy in the case of R.A. engravers shall not be filled up until the assent of the General Assembly has been taken by vote. Since the making of that law only two vacancies have occurred. They were both filled up without a preliminary permission, and the Sovereign sanctioned the election. On your contention, therefore, the custom consecrated by these sanctions must override the law itself, and nothing at this time stands between Barlow and the Queen's signature to his Diploma.

The Constitutional question you have raised is certainly one of the highest importance, and I shall watch its development with great interest. It is a matter of little moment what the view of an ordinary member like myself may be, but not so with the President, and I offer no apology for endeavouring to throw light upon the subject.

H.T.W.

The following letters from Leighton to Mr. Wells give an insight into the kind of work which his office of President entailed, and of the characteristically thorough manner in which Leighton fulfilled them.

Thursday Evening, 1879 or 1880.

Dear Wells,—I have noticed during my last two sittings at your studio, that, whenever the deeply interesting subject of our Academy appeared on the tapis, it stood in the way of your work, and I have therefore purposely abstained, as you no doubt remarked, from going beyond the merest surface in the discussion of any of the points on which we have touched. I felt that the sittings I gave you being so few and so scantily measured out, the least I could do was not, wittingly, to make you lose your time. That is to say, I did not tell you to-day orally what I now write, namely, my impression on your proposed question concerning the Chantrey purchases. The characteristic straightforwardness and loyalty with which you wished me to be informed on the point beforehand will not permit me to be silent in regard to your view. I have looked with the greatest care into the extract from the will which we all have, and have given the matter that thought which is due to your earnest conscientiousness, and I have satisfied myself that the General Assembly is wholly without a locus standi in claiming to control the expenditure of the Chantrey trust moneys in any way whatever; those moneys never pass into its hands or come under its cognisance; they are paid into the hands of the president and treasurer, against their receipt, and are dealt with solely by the president and council for the time being. An attempt, therefore, on the part of the General Assembly to assume control in this matter is in my view out of order, and it would therefore be out of order to ask or answer a question based, as yours is, on that assumption. I think you will find this view in harmony with the opinion of the body; if it is largely challenged, I shall postpone the answer till I have taken a legal opinion, as the point is very important. Here are my cards on the table.—In haste, yours sincerely,

Fred Leighton.

Monday.

Dear Wells,—The usual stress of business has prevented me till now from thanking you for your note and valuable information; I shall, with great interest, turn to the passages you allude to as soon as I get a good opportunity, and what I read will have the greatest weight with me when I vote again on a purchase. It would not, however, touch my point in regard to the General Assembly, which can only interfere with a past purchase if it can be shown to be illegal; this can, of course, only be established by legal authority, and I am, myself, sorry that your first resolution does not run thus: That the President be requested to consult high legal authority as to whether such and such purchases are barred by the will of Sir F. Ch. If your misgivings on that head are shared by a majority the thing would pass immediately and undiscussed, almost.

As concerns your motion on the pension resolution, I own to much misgiving; I should not dream of alluding to this had you not yourself taken me aside about it the other day. I am so far at one with you in principle that I feel, I can't say how deeply, that it is our paramount duty to interpret in the largest and most elevated sense our duty to the art of the country that we may be worthy in the eyes of the enlightened portion of the community of our high place, and that it is equally incumbent on us to keep our personal interests vigilantly in sub-ordination. I think that one of the present resolutions militates against this last view, and I need not conceal from you that it has not my sympathy. I am, however, very strongly of opinion that the form of your opposition to it will not be supported, and that in your desire for a logical comprehensiveness, you will fail of your end, which by simple direct opposition to the particular measure on the principle you have already enunciated and explained, you might very probably, I believe, achieve. I need not, I think, assure you, my dear Wells, that nothing is further from my thoughts than any interference with a member's freedom; indeed, on that head my views are known to you; but I can't refrain from saying thus much to give you an opportunity of quietly thinking matters over (don't answer this) before Wednesday. After all, you want primarily to get rid of paragraph 6, not to ensure a dialectical triumph. If the alternative is between your Committee and the resolution as it stands, I feel absolutely convinced that you will be left in a very cold minority; but if you point out that paragraph 6 takes our bounties off the ground of necessity, our only tenable ground, in fact commutes a bounty into an unconditional claim (of a formidable pecuniary nature, too), you will march in, I can't help thinking, with flying colours.

Don't, I repeat, be at the trouble to answer this expression of the opinion of,—Yours sincerely,

Fred Leighton.

Monday, February 1, (?) 1881.

Dear Wells,—Since receiving your letter I have been so absolutely engrossed with business and work that I have not had time till now to answer it. I am sincerely glad you have asked for a little modification in the terms of the Lucy petition; meanwhile I have written to Gladstone, and my letter has been acknowledged with a promise to note its contents.

In regard to your Chantrey resolution, I feel that, after the manner of very busy men, I have written in haste and not made myself quite clear. I should like, first, to remove one apprehension which you seem to have entertained; however strongly I may be convinced of the correctness of my own view on the matter under discussion, I cannot too emphatically say that as long as the points at issue were still sub judice I should not countenance a purchase which should assume my view to be the right one; but no such postponement as would lead to this dilemma is to be feared; what I propose is this: as soon as ever we have closed the discussion on the schools, and whilst they are being printed in their amended form for final consideration, therefore, on Friday next, if we get through on Wednesday, or failing that on the 22nd or 23rd of February, the resolutions of Council will be put on the table in their rotation; as, however, the next step in the Chantrey affair is to merely hear my answer to your memorandum, and as I understand that discussion on it will not be expected till members shall have had it to consider at their leisure, I will read it and lay it on the table before I take up the resolutions of Council which stand on the paper before it, so that when it comes up for final discussion, presumably in the first days of March, it can be discussed and voted on with full mastery of the subject. It is on the agenda paper of THAT meeting that your affirmative motion will stand; it does not come into force till then, since it is contingent on the effect produced on your mind by my answer of Friday (or of the next meeting after).

With respect to Redgrave's motion, it may lead to a technical "censure" of the Council; but there are censures and censures, and nobody will suppose, certainly I never dreamt, that you meant to imply moral obliquity to us in regard to what we have done. I have not a word to object to what you advance about the right of complaint, but it does not exactly cover the case: if you caught us, say, taking our friends to the Exhibition (or ourselves) on Sunday, a matter on which no two opinions are admissible, then "a complaint" would be in its place; but in the matter of payment to Treasurer, two opinions may and do exist, and they can only be measured against one another by a vote, and a vote can only be taken on a motion.

Lastly, as to the new codification committee, I think with you, in strictest confidence, that —— was not a good choice; but he was chosen in the usual manner by a majority of votes: that your labours were not remunerated in the usual manner is an oversight, which, of course, must and shall be set right. There seems altogether, and your letter corroborates that impression, to have been much vagueness about the doings of the Committee as a Committee, though, as usual, much zealous work on your part. I do not gather that attendances were entered in a book, which is the machinery by which payment is generally regulated, and the Committee having lapsed without reporting to the Council on its labours (being a sub-committee of the Council of 1878, it lapsed by a natural death with that Council), the whole thing had fallen out of notice. I hope that the old sub-committee will put in their claims, which will very certainly be satisfied. The codification has frequently been in my mind, for I consider it of very great importance, but as it is my impression that I am considered to drive the work of the Academy full hard as it is, I have hesitated to impose more labours on my colleagues, even though I am always ready to share them.—Sincerely yours,

Fred Leighton.

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). "Elijah in the Wilnerness".

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). "Elijah in the Wilnerness".

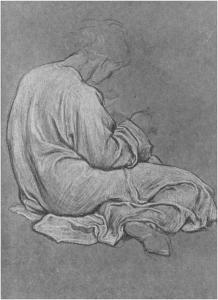

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). Sketch for "Elijah in the Wilnerness".

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). Sketch for "Elijah in the Wilnerness".

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). "Neruccia".

1879. Frederick Leighton (age 48). "Neruccia".

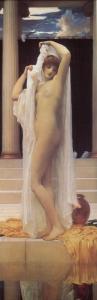

Around 1890. Frederick Leighton (age 59). "The Bath of Psyche". Model Ada Alice "Dorothy Dene" Pullen (age 31).

Around 1890. Frederick Leighton (age 59). "The Bath of Psyche". Model Ada Alice "Dorothy Dene" Pullen (age 31).

Psyche: Psyche is the Greek goddess of the soul. She was born a mortal woman, with beauty that rivaled Aphrodite.

Tuesday Morning, 2 Holland Park Road, Kensington, W., March 18, 1884.

Dear Wells,—Thank you for your letter received yesterday, which only lack of time prevented me from answering at once. I am happy to say that Richmond cheerfully acceded to my wish in regard to clauses 6 and 7. I do not think with Calderon, who has written to me, that the words of a man so high-minded as Richmond will indispose members in this matter, and, though I feel the importance of raising no prejudice against the proposal as keenly as ever, still wish him to initiate it. It is, I agree with you, a pity that the question of the retiring pensions must come off first; but that is, I fear, quite unavoidable, and it connects itself with the very first resolution. I assure you, my dear Wells, that I see the bearing of all you say on this head as plainly as possible, and have done so all along; but it does not prevail with me, because it does not cover the whole ground, and because I do not anticipate the dangers for which you think it might be used as a precedent.

In view of my own personal painful position in this matter, I shall ask the Assembly not to ratify the clause which affects me.—In great haste, yours sincerely,

Fred Leighton.

Leighton's official life, as understood and carried out by him, entailed infinitely more strain and occupation than can be described in these pages, but, notwithstanding, unless the call away from his easel was imperative, he kept certain hours in the day sacred to his art. These were from 9 A.M. till noon, and from 1 P.M. till 4. It was only in the off hours that he got through his other labours, which he performed, nevertheless, with most assiduous conscientiousness.

Among his duties outside the Academy were those at the British Museum. Mr. H.A. Grueber, Keeper of the Coins and Medals, writes: "Sir Frederic Leighton was elected a Trustee of the British Museum on May 14, 1881. He was an active member of the Standing Committee, who practically manage the affairs of the Museum, and he took great interest in the place. He was also a member of the Sub-committees on Buildings, on Antiquities, Prints and Drawings, also of those on Coins and Medals."

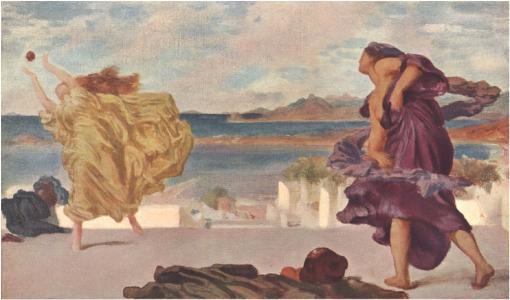

In the first R.A. Exhibition after his election, three pictures of the eight Leighton sent have, I think, a special interest—"Elijah in the Wilderness" (the picture into which he said he put more of himself than into any other he had painted up to that time); the portrait of his very dear friend Professor Costa, painted in the previous autumn at Lerici, and the head "Neruccia." Leighton with Costa studied the methods used in painting by the Venetians and Correggio, and Costa wrote the following with reference to them:—

The result of these studies and of the experience of years was that Leighton and I definitely adopted the following method. Take a canvas or panel with the whitest possible preparation and non-absorbent—the drawing of the subject to be done with precision and indelible. On this seek to model in monochrome so strongly that it will bear the local colours painted with exaggeration, and then the grey, which is to be the ground of all the future half-tones; on this paint the lights, for which use only white, red, and black, avoiding yellow, and, stabbing (botteggiando) with the brush while the colour is wet, make the half-tints tell out from the grey beneath, which should be thoroughly dry. When all is dry, finish the picture with scumbles (spegazzi), adding yellow to complete the colour.

Leighton formed his method of painting from these general maxims, and he painted my portrait at Lerici on these principles as an experiment, and then in 1878 we adopted the system definitely. For this portrait he had four sittings—one for the drawing and the monochrome chiaroscuro, one for the local colours; then, having covered all with grey, he painted the lights with red, white, and black, making use of the thoroughly dried grey beneath for his half-tints. With scumbles he completed the colour and the modelling.

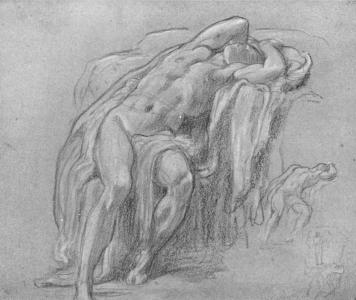

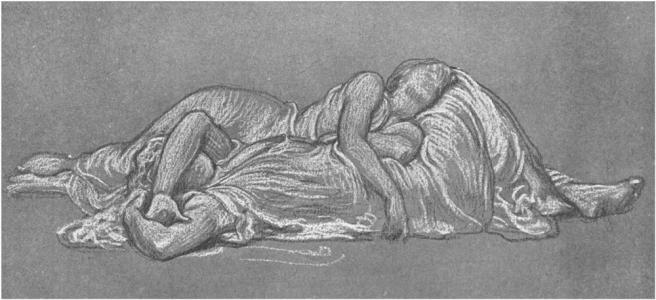

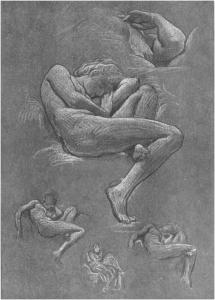

1892. Frederick Leighton (age 61). "And The Sea Gave Up The Dead Which Were In It". Sketch for Complete Design.

1892. Frederick Leighton (age 61). "And The Sea Gave Up The Dead Which Were In It". Sketch for Complete Design.

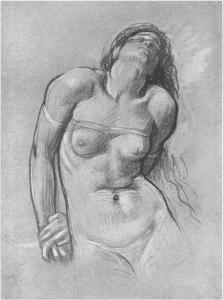

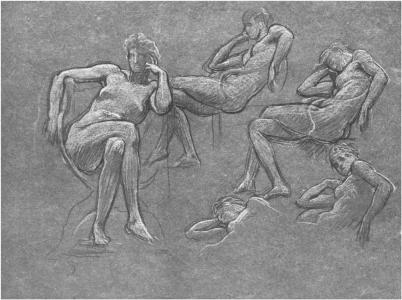

1886. Frederick Leighton (age 55). Study For Figure In Frieze, "Music." Leighton House Collection

1886. Frederick Leighton (age 55). Study For Figure In Frieze, "Music." Leighton House Collection

1890. Frederick Leighton (age 59). Study For "Andromeda." Leighton House Collection.

1890. Frederick Leighton (age 59). Study For "Andromeda." Leighton House Collection.

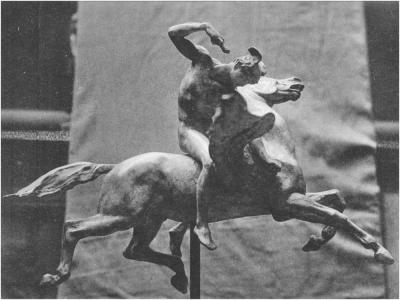

1891. Frederick Leighton (age 60). From Sketch In Clay For Perseus, In The Picture "Perseus And Andromeda."

1891. Frederick Leighton (age 60). From Sketch In Clay For Perseus, In The Picture "Perseus And Andromeda."

Frederick Leighton. Study For Figure In Panel In Royal Exchange—"Phœnicians Bartering With Britons". Leighton House Collection.

Frederick Leighton. Study For Figure In Panel In Royal Exchange—"Phœnicians Bartering With Britons". Leighton House Collection.

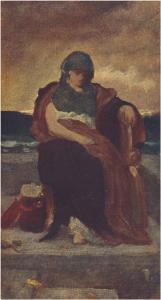

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). "Cymon and Iphigenia". Models sisters Ada Alice "Dorothy Dene" Pullen (age 25) and Isabella Helena "Lena" Pullen (age 11).

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). "Cymon and Iphigenia". Models sisters Ada Alice "Dorothy Dene" Pullen (age 25) and Isabella Helena "Lena" Pullen (age 11).

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). "Kittens". Model Isabella Helena "Lena" Pullen (age 11).

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). "Kittens". Model Isabella Helena "Lena" Pullen (age 11).

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). Study In Colour For "Cymon And Iphigenia."

1884. Frederick Leighton (age 53). Study In Colour For "Cymon And Iphigenia."

1883. Frederick Leighton (age 52). Study For Sleeping Group For "Cymon And Iphigenia". Given by Lord Leighton to G.F. Watts, O.M., and given by the latter to the Collection in Leighton House

1883. Frederick Leighton (age 52). Study For Sleeping Group For "Cymon And Iphigenia". Given by Lord Leighton to G.F. Watts, O.M., and given by the latter to the Collection in Leighton House

As the exquisite fragments in pencil of cyclamen, bramble and vine branch,[68] explain most intimately Leighton's genius as a draughtsman, so this head of Neruccia appears to me, together with one other work, to explain most explicitly his genius as a painter—a modeller with the brush. In 1890 Leighton painted "The Bath of Psyche."[69] The modelling in the torso of this figure, and in the head of Neruccia, reach the zenith as exemplifying Leighton's individuality as a painter. They might truly earn for him the title—Praxiteles of the brush.

Note 68. See Chapter III.

Note 69. Now in the Tate Gallery, purchased under the terms of the Chantrey Bequest.