Archaeologia Volume 7 Section XIII

Archaeologia Volume 7 Section XIII is in Archaeologia Volume 7.

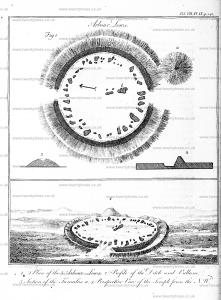

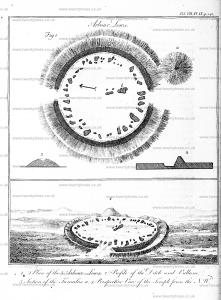

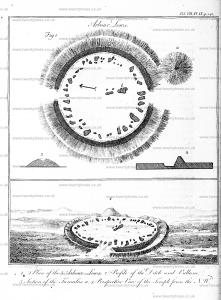

A Disquisition on the Lows or Barrows in the Peak of Derbyshire, particularly that capital British Monument called Arbelows [Map]. By the Rev. Mr. Pegge (age 80).

Arbor-Lows are an ancient monument, so well known in the country, that supposing a stranger desirous of visiting it (and indeed it is well worth visiting by the curious antiquary), and once arrived at Bakewell about five miles distant from it, he will not fail of meeting with a competent direction to the place.

We have various derivations given us by authors of this word Low, which as a substantive, and signifying an eminence or rising ground, obtains a sense quite contrary to that of the adjective low, humilis, which I suppose may be the Dutch word langa. This substantive enters the composition of a large number of local names, as an affix or termination, as here in Arbour-lows. I suppose there may be forty or fifty places with this termination in the small county of Derby (to say nothing of other countiesb), and chiefly in the Peak. Some deduce the word from the British llehau, locare, collocarec; others bring it 'from the Saxon word leʒ, liʒ, liʒe, or, according to the pronunciation of the Danes, loʒe, fignifying flame. As therefore Bustum denotes the place where a man was burnt and buried, so did our anceltors, in imitation of [the Romans] call the place of burial Lowe, whether the bodies were burned or notd. This latter,' says Mr, Hearne,. 'seems to be the more true etymology, because in Scotland, and the northern parts of England, the flame of any fire is called low to this day, &c.' But to me these etymologies appear far fetched and embarrassed, and therefore it would be far better to look diretly to the Saxon hlaeþ, or hlaþ, tumulus, or hille; Mr. Hearne himfelf acknowledging, that low signifies a hill amongst the hither Scotchmenf, that is, in the old English, And it is observable, that John Brompton too calls cumulus (or tumulus as I would amend it), a railed place of interment, a low for speaking of Hubba the Dane, who was slain A, D. 878, he has these words, 'Dani vero cadaver Hubbae inter occifos invenientes, illud cum clamore maximo fepelierunt, cumulum apponentes, quem Hubbelow vocaverunt, und sic usque in hodiernum diem locus ille appellatus est, et est in comitatu Devoniæg.' So that the word is Danish, it seems. as well as Saxon; and the Danes it is well known had great concerns all over the county of Derby. The whitlow, paronychia, so named from the white-top, which the levelling, when at maturity, commonly, exhibits answering to the French blanch-mal, shews plainly the general use of the word amongst us formerly, in the sense of a tumourh.

Note a. Junius in voce.

Note b. Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Devonshire, as below. Camden, col. 424.

Note c. Hearne, in Spelman's Life of Alfred, p. 61, from Dugdale's Warwickshire, p. 4.

Note d. Hearne, ibid.

Note e. Lye, Dict v. Hlaþ. Dugd. Warw. p. 5. Gawin. Douglas, p. 394, lin. 12.

Note f. Hearne, l. c.

Note g. Brompton, col. 809. This, in an old MS. Chronicle of mine, p. 131, js called Logge, the same in pronunciation, as is plain from the name that there follows, viz. Hubbeflowe. Another MS. Chron. p. 37, has Hubblow. So Leland in Collect. L p. 213, from Brompton., has 'Hublow, tumulus Hubbæ, in Devonia.'

Note h. In Derbyshire they call this complaint a wickslaw, very expressively. The last member is clearly a corruption of low or hlaþ, and as to the former part of the word, wick in the dialect of that country is the same as quick, and denotes consequently the beating or throbbing which always attends those painful tumours.

I observe next, that, in the Peak, they appropriate the termination low to those tumuli, which, in other parts of England, are called barrows, and suppose them to be places of sepulture. This is the notion of the common people, and they are undoubtedly such; for human bones have been found in many of them. Upon which ground alone, one may justly raise a question, whether all the villages and hamlets that present us with this word in the compolition of their names had not originally some tumulus or place of sepulture near them, though by cultivation, or other accidental causes, the low may now disappear. At many of the places fo denominated, the barrows are actually still remaining, as here at Arbour-Lows, &c.i, whence it is but reasonable to conclude, that lows of the same kind were once existing at all the places of the like termination.

Note i. Highlow, Blakelow, Ellocklow, Gallowlow, Hakeslow, Minninglow, Pidallow, Roundlow, Snipperlow, Stanhoplow, Whitelow, &c.

The general remarks which I have to make upon the lows are fuch as thefe,

First. They commonly are placed upon high groundk, and many of them upon the very brow or summit of hills, so as to be visible from considerable distances, and from which you have reciprocally very extensive views and prospects. This is the situation of Arbour-Low, Tidslow Topl, and those within the entrenchment upon Mam-Torr, to mention no more; and it is remarkable of the Arbour-Lows that the Eagle-Stone on Barlow High Bar, which is at least five miles distant, and undoubtedly a rock-idol, is seen from itm. So the old Chronicle cited by Mr. Hearne, 'And when the Danes fond Hungar and Hubba deid, thei bare theym to a mountayn ther besyde, and made upon hym a logge and lete call it Hubbslugh.n' Query, whether these elevated interments might not sometimes be intended to strike a terror into the breasts of the hero's enemies, since Weever relates of Vortimer, the British prince, that after his last victory over the Saxons he caused his monument to be erected at the entrance into Tanet, and in the same place of that great overthrow. 'In this monument, he commanded his body to be buried, to the further terror of the Saxons, that in beholding this his trophic, their spirits might be daunted at the remembrance of their great over-throw. As Scipio Africanus conceited the like, who commanded his sepulchre to be so set that it might overlook Africa; supposing that his very tombe would be a terror to the Carthaginianso.'

Note k. I know but one exception to this (others may recollect more), viz. that Earthen low was in the field on the left hand of the turnpike road leading from Mitham Bridge to Hope, at the N. W. corner of which the lane turns down to Brough. The field is in the liberty of Aston, and the estate of Thomas Eyre of Hassop, Esq. It is thirty yards in circumference, and is evidently a barrow. The top has been much higher in the memory of man, but the ground being here in tillage, the plough has lowered the summit considerably.

Note l. This is apparently a pleonafm, whence one may infer that the common people,. though they lived among the lows, and even had a right notion of them, as Hated above, did not perfedlly underhand the meaning of the word.

Note m. The British word for eagle is ergr; wherefore eagle here is probably a corruption of some British word of like sound, perhaps hyglod, famous, renowned. It is said there are two rock basons on the top of it.

Note n. Hearne, in Spelm. Life of Alfred, p. 4. See the passage from Brompton before cited, p. 132.

Note o. Weever's Fun. Mon. p. 519.

Be this as it may, the lows, 2ndly, are generally round. Indeed they are mostly so everywherep, though there are some few instances of an oblong-form, as what is called Julaberr's Grave at Chilham in Kentq, and another large barrow on Wye Downs, which, though upon a much larger scale, are not unlike our common gravesr. Barrows, I presume, almost naturally would take, if they mounted to any considerable elevation, a circular figure; for suppofing an human body of six feet laid upon the ground, and an agger of either earth or stones accumulated upon it to any height, the appearance at last will be nearly circular, and I may add, conical; by which, however, I do not mean to insinuate they may not often be flat at top, or concave like a bason, but only that the original construction was conical, and these other appearances accidental; flatness arising since, from time and weather, or perhaps in some cases from the plough; and concavity being caused by much the same fortuitous circumstances assisted by the known sinking and depression of a factitious mount of mold or earth; the same dishing may also happen, I conceive, even to a stone low.

Note p. Harris's Hist. of Kent, p. 137. Wormii, Mon. Dan. p. 33.

Note q. Harris's Hist. of Kent, p. 76.

Note r. See also Wormius, p. 37.

3dly. They are of various sizes and dimensions. We have them from sixty yards in circumference at the base down to four or five, and the presumption is, that the larger the barrow the greater was the dignity of the person interred. This, however, may be pronounced with some assurance, that the more august was the solemnity of the interment, either the greater pains were taken, or the more hands employed, which leads me to observe, that how the most stupendous of them for magnitude were compiled is not difficult to conceive, when one reflects, that sometimes a whole army were engaged in the services, and that for many days togethert.

Note s. Wormii Mon. Dan. p. 39,

Note t. Wormius, ibid.

4thly, As to the fubftance of our lows, they are fometimes compofed of fmall loofe ffones, rudely piled on heaps, without any order; others confift of the like ftones, but are covered with earth or turfu, which in other cafes may have accrued through length of time. Laftly, Some are entirely of earth or moldw.

Note u. Wormius, p. 43.

Note w. Such there were very anciently. Virgil, Æn. XI. 550. Tacitus, Annal. I. cap. 62. Dugd. Warw. p. 4.

5th. The greater stone-lows have sometimes smaller ones of the same kind scattered irregularly above them, as may be seen on Leam-Moor, Highlow-Moor, and Offerton-Moorx.

Note x. See Wormius, p. 41.

6th. Though such a multitude of lows are remaining, and especially in the Peaky, where they abound most, by reason that agriculture having taken but little place on the hills and moors; things continue there more in their ancient state, and have been less disturbed than in Scarsdale, or the other hundreds, where the lands have been more cultivatedz; yet many have been destroyed by the neighbouring inhabitants; those which consisted of grit-stones having some been totally, and others in part, carried away, to make wallsa. The materials of one of Robin Hood's Pricks, as they are called, was used in making the turnpike road leading from Sheffield to Grindleford-Bridge. So again, where the body of the low has been of lime-stone, it has been partly carried off by the farmers or grafters for making lime, as has been the case at Stanhope-Low, and Mining-Low. Some lows, moreover, have been disturbed through curiosity, or avarice; as when they have been rummaged and fought into from a hope of finding antiquities, or by others in expectation of meeting with hidden treasure. There are instances, lastly, where rabbits having burrowed in lows, a great disordering of the stones has ensued from those who have gone to hunt them, and dig them out. Sir Henry Spelman observes, that it is from the lows, or barrows, the 'cuniculorum oculamenta et habitacula Berries dicimusb.'

Note y. There are a great number of fmall ones on Leam-Moor, befides eight large ones.

Note z. See Dugd. V arw. p. 3. Plott, Oxfordsh. c. x. and Staffordsh. c. x.

Note a. A gentleman assured me, he himself had taken one entirely away, for that purpose, from Leam-Moor.

Note b. Sir H. Spelman's Gloss. v. Bergium.

7th. To enquire next into the use, or meaning of the lows. It cannot be doubted, after the various discoveries that have been made by digging and searching into them, that they are all places of sepulture, bones, ashes, urns, &c. paving been actually found in many of themc; besides, kist-vaens, and stone coffins, have been discovered in themd. It may be necessary, however, here to insert the following precaution. There have been lead mines worked in the Peak from remote antiquity; so that all the tumuli there found may not be lows, or places of interment, but some of them only heaps of rubbish ejected from the mine. A careful observer, nevertheless, will easily distinguish a low from a grove-hillock, as they call it; as the component subftance of a low is always very different, and there is rarely any mine near hand. The caution, however, may be useful to strangers, who visit the country for the sake of contemplating the lows. The stone lows cannot possibly be mistaken.

Note c. Four urns were found in Robin Hood's Prick abovementioned, one in a low on Leam-Moor. See Camden, col. 763. 425. note g below.

Note d. As in Aldwark-Moor. See Camden, col. 423,

8th. But now as these tumuli, or modes of interment, were, common to all countriese, and Britons, Romans, Saxons and Danes, have all, in their order, frequented the Peak of Derbyshiire, and have there been settled, the principal difficulty is to determine to which of those nations our numerous peakish lows belong. For my part, I incline to believe, they may have appertained not to any one particular, but to all those several people.

First, some are British, for kist-vaens have been found in many of themf; and besides, these have no regard to roads, as Roman tumuli would have, but are disperfed on moors, in various parts of the country, and mostly placed on eminences. In some of them again, such valuables have been found as are known to have been peculiar to the Britons; rings, beads, &c.g. Where therefore such circumstances as these are attendant, and the low is withal very large, and on some eminence, one may rationally conclude it to be British.

Note f. See above, art. 7.

Note g. In a stone low on Stanton Moor, which has been much rifled, not only bones were found, but a large bead of blue glass with orifices not larger than the tip of a tobacco-pipe. Some rings and beads were found in a low on Leam-Moor by Mr. Jonathan Oxley.

2nd. As lows, or barrows, were used by the Romans, if any appear near their roads (as on the Bath-way, from Brough to Buxton), and Roman coins, urns, or any implements acknowledged to belong to that people, are discovered in the body of the low, such low may reasonable be prefumed to be of Roman erection.

3. The Saxons, on their coming into these parts about A.D. 584, may with a great degree of probability be supposed to bring this mode of interment along with them from their own country; however, upon their establishment here, they would naturally learn and adopt it from the inhabitants of Mercia, whether Britons or Romans. And therefore there is valid reason to imagine, that our lows may some of them be the handy works of this nation, before its conversion to the Christian faith.

Lastly, many of the lows are probably of Danish original. This people flourished long in these parts, and Mr. Hearne says, 'It was the common way of burial with the Danes to raise tumuli upon the bodiesh.' Brompton above will testify that this was done for Hubba, insomuch that many of our lows are probably Danish, and those perhaps more especially, which have a circle of stones surrounding their base; this being a particular mode in Denmarki.

Note h. Hearne, in Sir John Spelman's Life of Alfred, p. 61. See also Wormii Mon. Dan. p. 33, alibi.

Note i. Wormii Mon. Dan. p. 35.

It would certainly be a very desirable thing, if one could be able, upon first view, to appropriate a low to its right nation; but this, it seems, as appears from the above short state of these matters, is not to be done, and therefore there can be no certainty, without prying into and examining the bowels and contents of them, and even that is hardly sufficient in all cases.

Having thus dispatched what I had to say on our lows in general, I proceed now more particularly to speak of Arbour-Lows, as being by far the most magnificent and capital Druidical remain of any we have in Derbyshire, not to lay in all this part of England. It may be considered as confining of two distinct articles, the lows and the temple as I shall call it at present. I shall take the lows first, as they denominate the whole of the group.

The lows, which are two, and therefore are properly exspressed plurally in the word Arbelows, are both of them of large dimensions. They stand on the brow of a hill, so as to be conspicuous afar of, both from the north and south, and therefore may be imagined to belong to persons of great account: and as arar in British means a hero, it seems probable, that this constitutes the first part of this compound namek; and then the sense of the whole will be, the barrows of the heroes, or great captainsl, answering to Knightlow in Sir William Dugdalem; and in fact, many of the lows had peculiar names, as is evident from the names of so many villages, which no doubt were at first borrowed and taken from their respective lows. Dr. Plott speaks of Arbour-low-close near Okeover, co. Stafford, where there is a lown; and perhaps this British or Celtic word may be the original of the Greek [Greek Text], and Latin Heros, Some possibly may fancy that Arvir may be the same person as Arvlragus mentioned by Juvenal, Sat. IV. v. 127, as a Briton, but Mr. Baxter will not allow that to be a proper nameo. Others may imagine, that Arbila, a British prince occurring in the old Scholiast on Juvenal, may be one of the persons here interred; but it is the height of rashness and extravagance to pretend to name a particular party: this therefore must necessarily be left in doubt.

Note k. Arar would be easily converted, or corrupted, to arbour; the insertion of b, euphonia gratiâ, does it at once.

Note l. It may be objected to this etymon, that by this means it is made an hybridous word, part British and part Saxon; but this is of little weight, as such kinds of compounds are common. Durosiponte, the Roman name of Godmanchester, is interpreted by Mr. Camden, a Bridge over Ouse. Britannia, col. 503. Besides, Arbour-Lows was not, as we have reason to think the original name, but was imposed afterwards by the Saxons or Danes; it being natural for either of these people, if they conceived Arar to be a proper name, as probably they did, to join it with an appellation of their own.

Note m. Dugdale, Warw, p. 5.

Note n. Dr. Plott, Nat. Hist. of Staffordshire, p. 404.

Note o. Essay on the Coins of Cunobelin, p. 57, feq.

The first low [Gib Hill Barrow [Map]] is on your right hand, if you are travelling southward. It is a large mount of earth, nearly round, of about eighteen feet diameter at the top, where there is a great hollow in the middle, in form of a bason, as is commonp. It is twenty-two yards diameter at the base. The original height to the top five yards two feet height on June 17, 1782, before it was opened three yards two feet. On the south side there is a low rampire of earth with several breaks in it, running across the field (at the distance of about seventy yards from the low) from the wall on the west, and under the wall on the east. These walls are plainly of modern erection; and whereas on the west side of that western wall no traces of the rampire are to be found, nor any place where it turned and being but an insignificant thing, it probably is of a late date too. However, it passes quite to the foot of that great rampire which environs the temple, N° 1. Pl. IX.

The other low [Arbor Low Henge Barrow [Map]] stands on the right hand of the southern entrance into the area of the templeq. It stands upon the grand rampire, which is a very extraordinary position, and is not above three or four yards removed from the said entrance. This again is a considerable pile of earth, nearly as big as the former, and with the like hollow, or bason, in the area of its top, only that the water which was lodged in it, has, from time to time, run over the interior edge next the fosse, and worn it away. It is natural to imagine, that this low, so singularly situated on the rampire of the temple, must have been of a later conftrusion than the temple itself.

Note q. See the plate.

Having done with the lows, I come to the temple [Arbor Low Henge and Stone Circle [Map]]. First, this is surrounded with a great circular rampire, measuring by its inward slope, seven yards high, and by the outward five. The fosse, which is within, and not on the outside of the rampire, is five yards over in the bottom.

2. The inclosed area is a circular flat of fifty-eight yards diameter, and has been encompassed by thirty-two very large stones, or more, of lime-stone, or grey-marble, placed circularly. The stones formerly stood on end, two and two together, which is very particular, and different, I think, from any other stone circle now known; however, they all lie flat now, and are some of them so much broken by their fall, that it requires some attention in observing and numbering them; for the fragments are not only some bigger than others, as would necessarily happen, but sometimes lie at a small distance from the principal or larger pieces, to which they respectively belonged. However that they stood in pairs at first, is very obvious, and it is probable they were brought, as there is no quarry nearer, from Fairdale or Ricklow Dale which is very near; for they are apparently the same sort of stone, but blanched by the weather.

3. The two entrances into the temple, nine yards each, are nearly south and north, but inclining to the south west and north east, and, as was observed, the slight rampire from the other low comes up to the southern entrance. The entrances are level, being banks of earth across the fosse (the earth in these places having never been dug away), and they both of them had, on each hand, one of the stone pillars abovementioned, between which you entered into the grand area. I call them pillars now, though they are flat stones, because, as has been already noted, they stood on end, and were so lofty.

4. In the area lies one very large stone four yards one foot long, two yards two foot wide, perhaps not less than three or four ton weight. There is another to the north of it, and a third on the east side, which appears to have been much broken. If ever there was a fourth on the west side it is now gone.

The questions then arise, to what nation, British, Roman, Saxon or Danish, did this magnificent flrufture belong? and what was it designed for, a temple, a place of inauguration, a forum, or a sepulchre? these questions I shall endeavour to resolve.

1. I have met with those who have esteemed it a Roman work; but do we hear of any thing of the kind in Italy? and if there were rampires only, without the pillars or stones, I should not account it a Roman fortification, because it is circularr, and the fosse is on the inside of the vallum. However, the stones placed in a circular manner in the area, not to mention those in the middle, form an invincible objection to any pretensions the Romans can possibly make to this monument, as likewise does the low on the south eaft corner of the rampire, which is indeed very singular, and the like to which is never found on any Roman vallum.

2. The Saxons appear to have no better claim than the Romans. We know not that this people had any great skill in mechanics, s as to be able to raise stones of such vast weight as these. They were extremely rude and ignorants when they came into Mercia under Crida A. 584, and had enough to do, no doubt, for the first fixty years, to maintain their ground, and form a settlement in the country; and A. 644 the Mercians were converted to Christianity, and then there would of course be an end of all undertakings of this fort. These Saxons, moreover, so extremely illiterate, would necessarily derive all their knowledge and skill in the arts from the Romans left in the island, or the Romanized Britons, who not only were Christians, but probably had no knowledge or experience this way, any more than themselves. Indeed one cannot help thinking, that a monument of fuch a grand and lately appearance, and so conspicuous, as this must have been when in its original perfection, and the component stones all standing upright, would certainly have been noticed in the Saxon Chronicle, or some other of our writers, had it been erefled either by the Saxons or Danes. Hubbalow, you observe, is mentioned, and though it must be allowed our accounts of their times are not so ample and particular as one would wish, yet they are far more copious than any we have (if you except the fabulous History of Jeffrey of Monmouth), and his followers of the old British affairs.

Note r. The ground here would have admitted of any figure; and the Romans, it is well known, made their camps either fquare or oblong, where they could.

Note s. Assemblage of Metrop. Coins of Canterb. p. 40.

The Danes were much in the same predicament with the Saxons. At first, they were meer rovers, and even at that time, Christianity was the religion professed in the country, to which they were soon converted. They never were so powerful, or so far settled, as to accomplish such a noble work as Arbour-lows till their conversion; and after that, they never would think of attempting it.

The Britons then are the only people, to whom with any colour of reason one can think of ascribing this august monument; and indeed it has the air and aspect of very remote antiquity. They had arts and methods of elevating stones even of superior weight and dimenfions to thoset, and had also accomplished works, as we have reason to think, of far greater exertion. But though we adjudge the main body of this monument to the Britons, yet the lows, which we have made a distinct branch, do not so certainly belong to them. They appear superior in time to the temple, as stated above, but nevertheless they may be theirs; on the other hand, they may be Roman or Saxon or Danish, insomuch that at present we dare not presume to decide upon a point, which probably will be more satisfactorily determined by the contents of the lows, if ever hereafter they may happen to be opened.

Note t. Dr. Borlase, p. 157.