Grave Mounds and their Contents by Llewellynn Jewitt

Grave Mounds and their Contents by Llewellynn Jewitt is in Prehistory.

A Manual Of Archeology, As Exemplified In The Burials Of The Celtic, The Romano-British, And The Anglo-Saxon Periods. By Llewellynn Jewitt (age 53), F.S.A. With Nearly Five Hundred Illustrations. London: Groombridge And Sons, 5, Paternoster Row. 1870.

To My Old And Much-Esteemed Friend, Joseph Mayer, Esq., Fellow Of The Society Of Antiquaries Of London; Fellow Of The Royal Society Of Northern Antiquaries Of Copenhagen; Fellow Of The Royal Asiatic Society; Member Of The Societies Of Antiquaries Of France, Normandy, The Morini, Etc., Etc., Etc.; One Of The Most Ardent And Zealous Of Archaeologists, And Most Kindly Of Men; The Princely Donor To The Public Of The Finest And Most Extensive Museum Of Antiquities Ever Collected Together By A Single Individual; I, With True Pleasure, Dedicate This Volume, Llewellynn Jewitt.

Contents.

Chapter I. Grave-Mounds In General - Their Historical Importance - General Situation - Known As Barrows, Houes, Tumps, And Lows - List Of Names Division Into Periods

Chapter II. Ancient British Or Celtic Period - General Characteristics Of The Barrows - Modes Of Construction - Interments By Inhumation And By Cremation Positions Of The Body - Hitter Hill Barrow - Elliptical Barrow At Swinscoe Burial In Contracted Position In Sitting And Kneeling Positions Double Interments

Chapter III. Ancient British Or Celtic Period Interment By Cremation - Discovery Of Lead Burial In Urns - Positions Of Urns - Heaps Of Burnt Bones Burnt Bones Enclosed In Cloth And Skins - Stone Cists - Long-Low - Liff's-Low, Etc. - Pit Interments Tree-Coffins

Chapter IV. Ancient British Or Celtic Period Sepulchral Chambers Of Stone - Cromlechs - Chambered Tumuli - New Grange And Dowth - The Channel Islands - Wieland Smith's Cave, And Others - Stone Circles - For What Purpose Formed - Formation Of Grave-Mounds Varieties Of Stone Circles - Examples Of Different Kinds - Arbor-Low, Etc.

Grave Mounds and their Contents Chapter II General Characteristics

Ancient British, or Celtic, Period - General characteristics of the Barrows - Modes of construction - Interments by inhumation and by cremation - Positions of the body - Hitter Hill Barrow - Elliptical Barrow at Swinscoe - Burial in contracted position - In sitting and kneeling positions - Double interments.

Grave Mounds and their Contents Chapter IV![]()

Ancient British or Celtic Period Sepulchral Chambers of Stone - Cromlechs - Chambered Tumuli - New Grange and Dowth - The Channel Islands - Wieland Smith's Cave, and others - Stone Circles - For what purpose formed - Formation of Grave-mounds Varieties of Stone Circles - Examples of different kinds - Arbor-Low, etc.

One of the most important classes of barrows is that which contains sepulchral chambers of stone; not the simple cists which have been spoken of in the preceding chapter, but of a larger, more complicated, or colossa character. Mounds of this description exist, to more or less extent, in different districts. In most instances the mound itself, i.e., the earth or loose stones of which the superincumbent mound was composed, has been removed, and the gigantic sepulchral chamber alone left standing. In many instances the mounds have been removed for the sake of the soil of which they were formed, or for the purpose of levelling the ground in the destructive march of agricultural progress. In many cases, however, they have doubtless been removed in the hope of rinding treasure beneath; it being a common belief that immense stores of gold in one instance the popular belief was that a "coach of gold" was buried beneath were there for digging for. Where the mounds have been removed, and the colossal megalithic structures allowed to remain, they have an imposing and solemn appearance, and seem almost to excuse the play of imagination indulged in by our early antiquaries in naming them Cromlechs, and in giving to them a false interest by making them out to be "Druids' altars" - altars on which the Druids made their sacrifices. These same authorities have, indeed, gone so far in their inventions as to affirm, that when the capstone was lower on one side than another, as must necessarily frequently be the case, it was so constructed that the blood of the victims might run off in that direction, and be caught by the priests; that some of the naturally formed hollows in the stones were scooped out by hand to receive the heart and hold its blood for the highest purposes; and that when the cromlech was a double one, the larger was used for the sacrifice, and the smaller for the Arch-Druid himself whilst sacrificing.

Researches which have been made in recent times show the absurdity of all this, and prove beyond doubt that the cromlechs are neither more nor less than sepulchral chambers denuded of their mounds. In several instances they have been found intact, and, these mounds being excavated, have been brought to light in a perfect state. These instances have occurred in Cornwall, in Derbyshire, and in other districts of England, as well as in the Channel Islands and elsewhere. One instance is that of the Lanyon cromlech [Map] in Cornwall. It seems that some seventy years ago "the farmer" to whom the ground belonged cast a longing eye on what appeared to be an immense heap of rich mould, and he resolved to cart it away and spread it over his fields. Accordingly he commenced operations, his men day after day digging away at the mound, and carting the soil off to the fields. By the time some hundred cart loads or so had been removed the men came to a large stone, which defied their efforts at removal, and, not knowing what it might be, or what it might lead to, they went on removing the surrounding earth, and gradually cleared, on all its sides, the majestic cromlech which is now one of the prides of Cornwall.

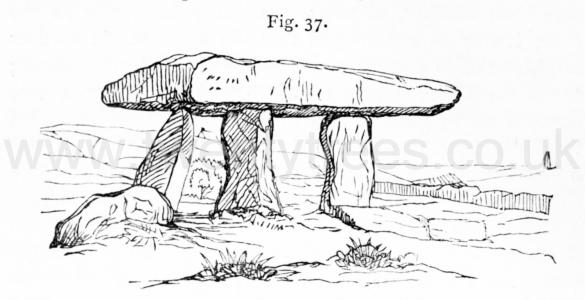

This highly interesting chamber contained a heap of broken urns and human bones. This "Lanyon cromlech," a view of which is given on fig. 37, consists now of three immense upright stones, on which rests an enormous capstone, measuring about eighteen and a half feet in length and about nine feet in width, and is computed to weigh above fifteen tons. How such stones were raised and placed on the rough upright stone supports which had been prepared for them is almost beyond comprehension, when it is recollected that they were raised by a people who were devoid of machinery.

"The heart,

Aching with thoughts of human littleness,

Asks, without hope of knowing, whose the strength

That poised thee here."

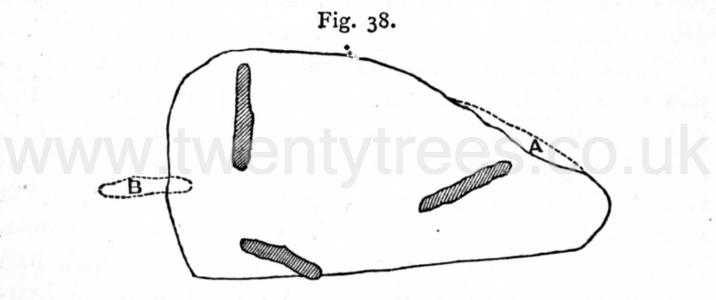

This cromlech when first uncovered consisted of four upright stones, on which rested the capstone. In 1815, during a tremendous storm, the capstone and one of the supports were thrown down. In 1824 the capstone was replaced, under the superintendence of Lieut. Goldsmith, R.N., and at this time a piece was broken off at A. The fourth upright stone was not replaced, having been broken when thrown down. Fig. 37 shows the cromlech as replaced. Fig. 38 is a plan of it, showing the uprights and the capstone. The large outline is the capstone, the part marked A being the part broken off; the shaded parts are the present three uprights; and B the fourth upright, broken.

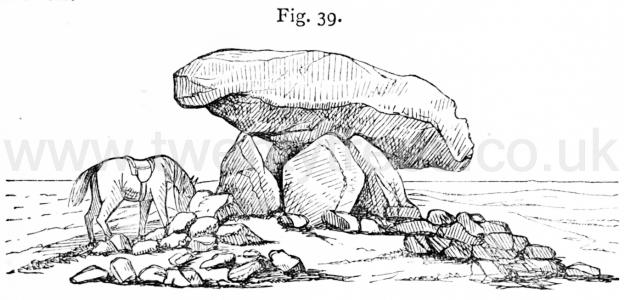

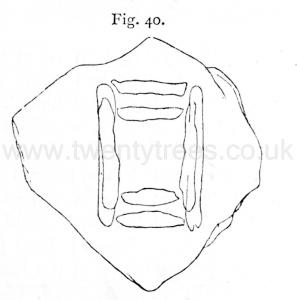

Kits Cotty House [Map], in Kent; the Chun [Map] cromlech, in Cornwall (figs. 39 and 40) the covering stone of which is calculated to weigh twenty tons; the Molfra [Map] cromlech, in the same county, which consists of a compact cist closed on three sides and open on the fourth; the Zenor [Map] cromlech; the Plas-Newydd cromlech, and many others which it is not necessary to enumerate, are all of the same class. The Plas Newydd (fig. 41) is a double cromlech, the two chambers being close together, end to end. The capstone of the largest, which is about twelve feet in length by ten feet in breadth, originally rested on seven stones, two of which have disappeared. The two erections undoubtedly were originally covered with a single mound.

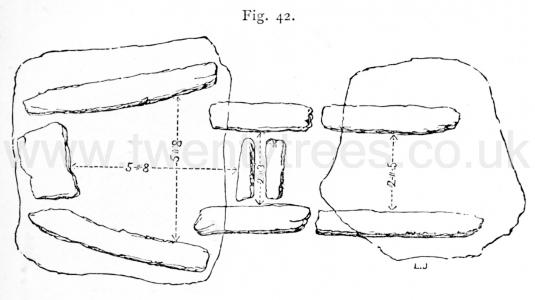

At Minninglow [Map], in Derbyshire, erections of this kind occur, but, not being denuded of their mounds, are still partially buried. The mound is of large size. Under the centre and in four places in the area of the circle are large cists, which if cleared from the earth would be fine cromlechs of precisely the same form as those just described. They are formed of large slabs of the limestone of the district, placed upright on the ground, and are covered with immense capstones of the same material. All these chambers had contained interments. The accompanying plan (fig. 42) of some of these cists gives the situation of the stones forming the sides of the large chamber; of the passage leading to it; of the slabs which closed its entrance; and of the covers or capstones. The chamber is rather more than five feet in height, and the largest capstone about seven feet square, and of great thickness. A kind of wall similar to those which have been found to encircle some of the Etruscan tumuli, forms the circle of this mound, which rises to a height of more than fifteen feet from the surface of the ground1.

The general arrangement of this example will be seen to bear an analogy to the Plas Newydd [Map] and others spoken of, and shows by what an easy transition the building of galleries, or a series of chambers for family tombs, in these large mounds, would be arrived at. Of this kind some very large examples exist in Ireland, and in the Channel Islands, as well as in various parts of England.

Note 1. It is worthy of remark, that this noble mound, with its very early interments, has been made a place of sepulture in more recent times, many Roman coins and remains of that period having been found there.

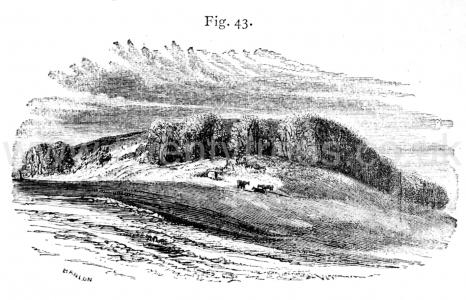

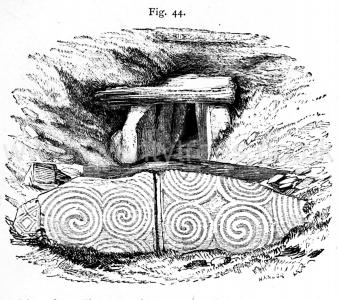

One of the most important in size, as well as in general interest, is the one at New Grange [Map], county Meath. "The cairn, which even in its present ruinous condition measures about seventy feet in height, and is nearly three hundred feet in diameter, from a little distance presents the appearance of a grassy hill, partly wooded; but upon examination the coating of earth is found to be altogether superficial, and in several places the stones, of which the hill is entirely composed, are laid bare. A circle of enormous stones, of which eleven remain above ground1, originally encircled its base. The opening (of which an engraving is shown on fig. 44) was accidentally discovered about the year 1699, by labouring men employed in the removal of stones for the repair of a road. The gallery, of which it is the external entrance, extends in a direction nearly north and south, and communicates with a chamber, or cave, nearly in the centre of the mound. This gallery, which measures in length about fifty feet, is at its entrance from the exterior about four feet in height, in breadth at the top three feet two inches, and at the base three feet, five inches. These dimensions it retains, except in one or two places, where the stones appear to have been forced from their original position, for a distance of twenty-one feet from the external entrance. Thence towards the interior its sides gradually increase, and its height where it forms the chamber is eighteen feet. Enormous blocks of stone, apparently water-worn, and supposed to have been brought from the mouth of the Boyne, form the sides of the passage; and it is roofed with similar stones. The ground plan of the chamber is cruciform; the head and arms of the cross being formed by three recesses, one placed directly fronting the entrance, the others east and west, and each containing a basin of granite. The sides of these recesses are composed of immense blocks of stone, several of which bear a great variety of carvings2. In front of the entrance (fig. 44) will be seen one of these carved stones.

Note 1. These immense monoliths have originally, it is estimated, been upwards of thirty in number, and to have been placed probably ten yards apart. The largest remaining stone stands between eight and nine feet above the ground, and is seventeen feet in circumference. It is estimated to weigh upwards of seven tons. Several of the stones have entirely disappeared, of others fragments remain scattered about.

For an excellent notice of this and other remains, the reader is referred to Mr. W. F. Wakeman's "Handbook of Irish Antiquities," the best and most compact littlework on the subject which has been issued, and one which will be found extremely useful to the archaeological student to which I am indebted for some of the accompanying engravings.

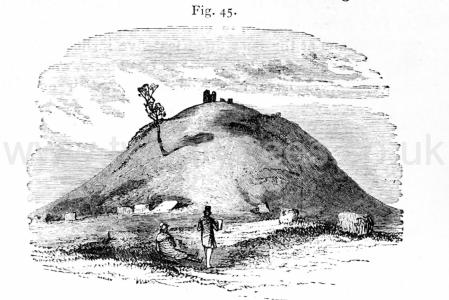

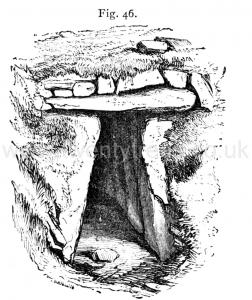

At Dowth [Map] and Nowth [Map] (Dubhath and Cnobh), very similar chambered tumuli exist, the former of which is also remarkable for its sculptural stones, which bear a strong resemblance to those at New Grange. The Cairn of Dowth here engraved (fig. 45), is of immense size, and contains a cruciform chamber similar to that at New Grange, with a passage twenty-seven feet in length, composed as was the chamber of enormous stones. On some of the stones were carvings and Oghams. The mouth of the passage leading to the cruciform chamber is shown on fig. 46.

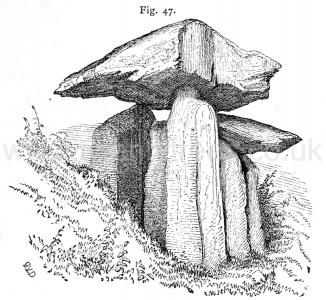

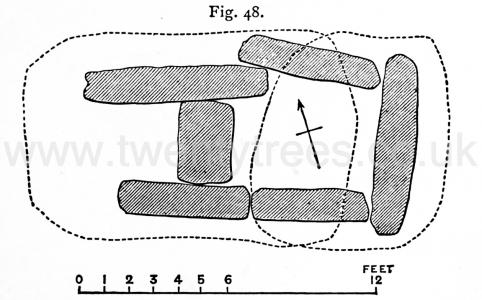

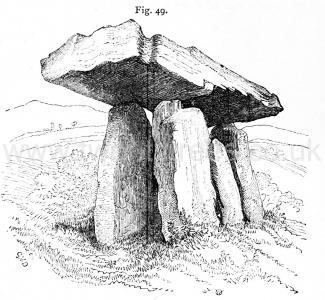

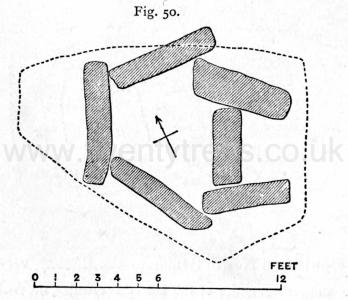

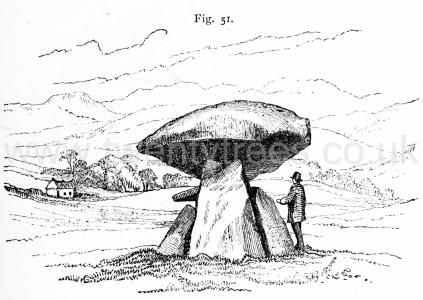

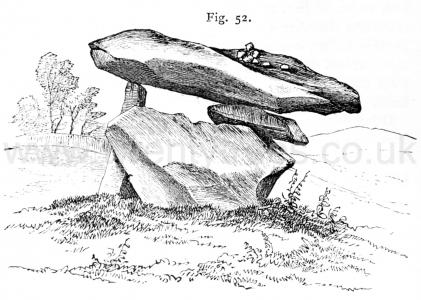

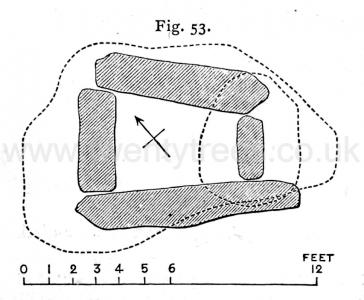

Other excellent examples of Irish cromlechs and chambers are those at Monasterboise ("Calliagh Dirras House") [Map]; Drumloghan (full of Oghams) [Map]; Kells; Knockeen [Map] (figs. 47 and 48); where the right supporting stones are six in number, and arranged rectangularly, so as to form a distinct chamber at the S.E. end, the large covering stone being 12 feet inches by 8 feet, and weighing about four tons, and the smaller one about half that size; Gaulstown [Map] (figs. 49 and 50, the inner chamber of which measures 7 feet by 6 feet 4 inches, and is seven feet in height); Ballynageerah (figs. 51, 52, and 53), the capstone of which is cleverly and curiously poised on two only of the upright stones, as will be seen by the engravings1; Howth, Shandanagh, Brennanstown, Glencullen, Kilternan, Mount Brown, Rath-kenny, Mount Venus, and Knock Mary, Phoenix Park, as well as at many omer places.

Note 1. For the loan of these seven engravings I am indebted to the Council of the "Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland," (formerly the "Kilkenny and South-east of Ireland Archaeo'ogical Society,") in whose journal one of the most valuable of antiquarian publications they have appeared. This Association is one of the most useful that has ever been established, and deserves the best support, not only of Irish, but of English antiquaries.

In the Channel Islands the indefatigable and laudable researches of Mr. Lukis (age 81) show that the galleried stone chambers of the tumuli in that district had been used by successive generations for many ages. One of the most important of these is the gigantic chambered burial place, surrounded by a stone circle, at L'Ancresse [Map], in Guernsey. In this, "five large capstones are seen rising above the sandy embankment which surrounds the place; these rest on the props beneath, and the whole catacomb is surrounded by a circle of upright stones of different dimensions. The length of the cromlech is 41 feet from west to east, and about 17 feet from north to south, on the exterior of the stones. At the eastern entrance the remains of a smaller chamber is still seen; it consisted of three or four capstones, and was about seven feet in length, but evidently within the outer circle of stones"1. In a careful examination made by Mr. Lukis (age 81), many highly interesting features were brought to light, of which he has given an excellent account in the "Archaeological Journal,"2 to which the reader cannot do better than refer. The engravings there given, show the interiors of some of the chambers, with their deposits in situ, and exhibit some of the highly interesting relics found during the excavations. The pottery was of a totally distinct character from that of the Celtic period found in England, some of the forms being of what are usally considered the Anglo-Saxon type, and are the result of the use of these chambers by successive generations, as already named.

Note 1. F. C. Lukis.

Note 2. Vol. I. p. 142.

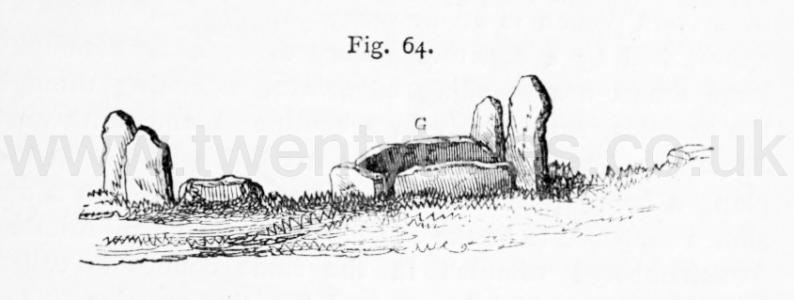

The chambered tumulus, called the "Five Wells [Map]," near Taddington, of which an engraving is here given (fig. 64), has been a mound of large size, and the chambers and passages, or gallery, have been extensive. A plan of this tumulus is given in fig. 65. The "Five Wells [Map]" tumulus consists of two vaults or chambers, situated near the centre of a cairn (which is about thirty yards in diameter), each approached by a separate gallery or avenue, formed by large limestones standing edgeways, extending through the tumulus, respectively in a south-east and north-west direction. These chambers are marked B and G on the plan, G being the cist engraved on fig. 64. E E E are stones supposed to be the capstones thrown down. Another five-chambered tumulus in the same county is called Ringham-Low [Map], which has many interesting remains.

Another extremely important mound of this description is the one at Uley, in Gloucestershire [Map], of which an able account has been written by Dr. Thurnham.1 The mound is about 120 feet in length, 85 feet in its greatest breadth, and about 10 feet in height. It is higher and broader at its east end than elsewhere. The entrance at the east end is a trilithon, formed by a large flat stone upwards of eight feet in length, and four and a half in depth, and supported by two upright stones which face each other, so as to leave a space of about two and a half feet between the lower edge of the large stone and the natural ground. Entering this, a gallery appears, running from east to west, about twenty-two feet in length, four and a half in average width, and five in height; the sides formed of large slabs of stone, set edgeways, the spaces between being filled in with smaller stones. The roof is formed, as usual, of flat slabs, laid across and resting on the side-slabs. There are two smaller chambers on one side, and there is evidence of two others having existed on the other side. Several skeletons were found in this fine tumulus when it was opened, many years ago.

It will have been noticed that circles of stones surrounding grave-mounds have frequently been named in this and the preceding chapter. It will, therefore, be well to devote a few lines to these interesting remains.

Grave Mounds and their Contents Chapter V Pottery

Ancient British or Celtic Period Pottery Mode of manufacture - Arrangement in classes - Cinerary or Sepulchral Urns - Food Vessels - Drinking Cups - Incense Cups - Probably Sepulchral Urns for Infants - Other examples of Pottery.

Grave Mounds and their Contents Chapter VI

Ancient British or Celtic Period—Implements of Stone—Celts—Stone Hammers—Stone Hatchets, Mauls, etc.—Triturating Stones—Flint Implements—Classification of Flints—Jet Articles—Necklaces, Studs, etc.—Bone Instruments—Bronze Celts, Daggers, etc.—Gold Articles.

FLINTS

Flints, i.e., various instruments formed of flint, are undoubtedly the most abundant of any relics of the Ancient Britons found in or about grave-mounds. They are extremely varied in form, and many of them are of the most exquisite workmanship—such, indeed, as would completely baffle the skill, great though that skill undoubtedly is, of "Flint Jack"31 to copy. The arrangement, classification, and nomenclature of flints is at present so uncertain, and so mixed up with absurd theories, that it is difficult to know how to place them in a common-sense manner. All I shall attempt to do in my present work—which is intended to describe, generally, the relics to be found in the barrows of the period, and not to be a disquisition on flints alone—will be to give examples of some of the more usual forms which have from time to time been found, so as to facilitate comparisons with those of various districts and countries.

Note 31. For a memoir, with portrait, of this remarkable character, and an account of his doings, see the Reliquary, vol, viii., p. 65, et seq.

The dagger-blade variety is of what is usually called the "leaf-shaped" type, and is the prototype of the bronze dagger of a later period. The example here given (fig. 154) is from Green-Low, and is of remarkably fine form. Another, and of perhaps much finer form, is shown on the accompanying plate (fig. 155). It was found at Arbow-Low, in June, 1865, and is five and seven-eighths inches in length, and nearly two and a quarter inches in width in the centre. In its thickest part it is scarcely three-eighths of an inch in thickness, and is chopped and worked with the utmost nicety to a fine edge. It will be noticed that its sides, as they begin to diminish, are deeply serrated for fastening with thongs to the haft or handle. It is engraved the exact size of the original.