Antiquity 1936 Volume 10 Issue 40 Pages 417-427

Antiquity 1936 Volume 10 Issue 40 Pages 417-427 is in Antiquity 1936 Volume 10 Issue 40.

The Recent Excavations at Avebury by Alexander Keiller (age 45) and Stuart Piggott (age 24).

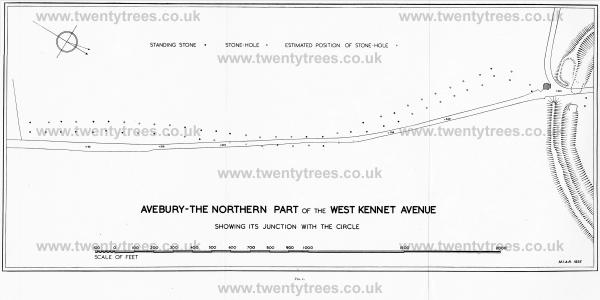

The most impressive megalithic monument in the world, which has come to be known as the ‘Avebury Complex', lies on a spur of the Middle Chalk running northwestwards from the main massif of the North Wiltshire Downs. Immediately to the west runs the river Kennet. The monument consists of an approximately circular bank with a ditch on its inner side enclosing a level area of 289 acres. On the inner edge of the ditch stood a circle of standing stones. Inside the circle again stood two interior settings of standing stones, each consisting of a double concentric circle, that to the north having in its centre three stones forming the so-called ‘Cove’ [Map], and that to the south a monolith. There was one original entrance through the bank and across the ditch at the south, and to this entrance an avenue (usually called ‘The West Kennet Avenue’) consisting of a double line of standing stones placed in pairs, averaging 50 feet apart transversely, and at average longitudinal intervals of 80 feet, led for a distance of over a mile from two small concentric stone circles on Overton Hill, known as ‘The Sanctuary [Map]’.

A second avenue, ‘The Beckhampton Avenue’, has sometimes been claimed to have run to the Avebury circles from the southwest, where two stones, ‘The Longstones [Map]’, stand, and were considered by Stukeley to be part of such an avenue. In the writers’ opinion, however, it seems more likely that, as originally suggested by Schuchhardt many years ago,1 the Beckhampton standing stones represent the remains of an independent stone circle with an avenue, of which Stukeley saw the remains, running from it towards the Kennet. It seems very improbable that an avenue to the Avebury Circles should have crossed the river as the assumed Beckhampton course would make it do, and the suggested interpretation has parallels at Stanton Drew, and, indeed, at Stonehenge itself.

Note 1. Prähistorisch Zeitschrift, 1910, II, 315.

In the case of Avebury the source of the stones was purely local. These were derived from the isolated boulders of the resilicified silicious sandstone known as ‘sarsen’. It would appear probable that to avoid the steep gradients entailed by a direct route the stones were transported to Avebury along the line followed by the West Kennet Avenue, presumably by means of haulage and rollers-a method of transport which in the case even of the larger stones has been proved by the writers, by experiment, to entail considerably less labour on level ground than might be supposed.

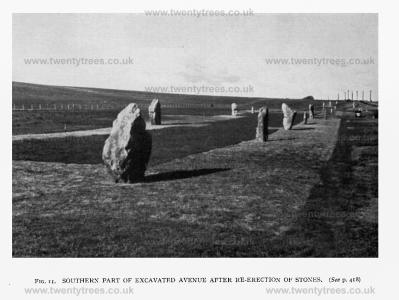

Excavations in the West Kennet Avenue were begun in 1934 by The Morven Institute of Archaeological Research under the joint direction of the writers. The primary purpose of these excavations was to establish the exact course followed by the avenue, and furthermore, if possible, to arrive at a definite date and culture for the construction of the monument. The opportunity was taken by the excavators of re-erecting all fallen stones, and stones which, as will be later described, were found to have been buried (FIG. 11). The entire course of the northern third of the avenue had been exposed by the end of 1935. Prior to excavation the only visible signs existing, for even the approximate course of this part of the avenue, consisted of three standing stones and nine others which were lying prone; a tenth had fallen and had been re-erected in 1912, but in an incorrect position as well as upside down.2 The evidence on which the excavators relied was naturally the discovery of the stoneholes or sockets in which stones had stood. All except one of these were satisfactorily identified; in the case of this stonehole (no. 15)3 there is no reason to suppose that no stone stood between nos. 13 and 17, but it may be presumed that the stonehole was so shallow as not to penetrate the subsoil.

Note 2. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XXXVIII, 7.

Note 3. The numbering of stoneholes and stones used in this article is that adopted for convenience during the excavations and begins from the southern end of the excavated portion, the left-hand stone to an observer facing Avebury being no. I and the right-hand no. 2 and so on.

The line of the avenue was found to have taken a different course from that which had been previously assumed. Its course was tortuous but not sinuous, being laid out in a series of relatively straight sections of varying lengths, and can better be followed by reference to the plan (facing p. 418) than from a verbal description or even by observation on the ground. It will be seen that the disposition of the stones becomes curiously irregular in the last section as the Avenue approaches the Circle, the longitudinal measurements increasing, and the breadth being reduced between the last pair of stones to only 34 feet. Aubrey's plans suggest a similar arrangement at the junction of the Avenue with the circles on Overton Hill, while the narrowing at least was confirmed during the excavation of this site.4? It is clear that the two massive stones of the outer Avebury Circle standing immediately behind the original causeway of the great ditch served as portal stones to the monument.

Note 4. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XLV, 306.

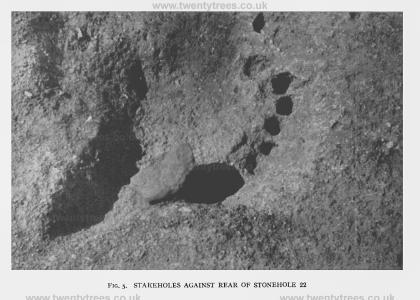

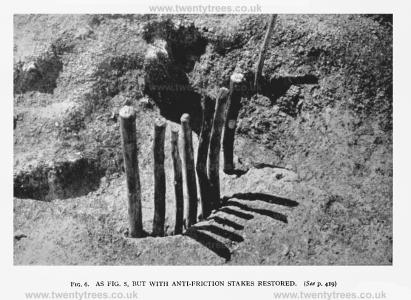

The stoneholes themselves must not be considered as cavities in which the stones were inserted for support, as might be the case with a posthole, but were uniformly rather shallow excavations into which, save in the case of certain flat-bottomed megaliths, were inserted entire boulders, fractured blocks of stone, or other packing material, to ensure greater stability. Considerable light was thrown during the excavations on the methods employed by the original erectors, impressions in the chalk to take supporting beams of timber, as well as stakeholes, being, in several cases, clearly visible. These stakeholes may be divided into two types. The first was represented by those situated some distance from the stoneholes themselves, which held stakes of considerable diameter, doubtless used for taking up the strain on ropes employed during the actual erection (32 on FIG. 2). The other type was considerably smaller in diameter than the foregoing, and held small stakes which were also used during erection but for reducing the friction of the stone against the wall of the stonehole (FIGS. 5 and 6). Groups of these were found in three stoneholes, in each case arranged in a roughly semicircular form against the steeper side (Nos. 21,22; and 38 on FIG. 2).

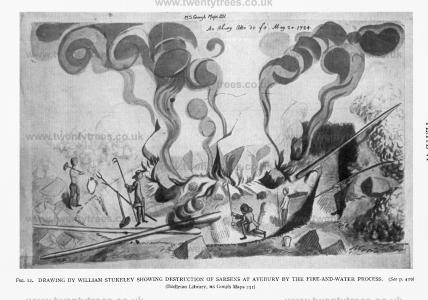

When Aubrey first visited Avebury in 1648 all the stones of the Avenue, standing or fallen, seem to have been still in existence, but nevertheless, deliberate destruction would appear to have begun about this time, and many of the stones broken up either by simple fracture or the more complicated method, which has been so graphically described by both Aubrey and Stukeley, of heating the stone and striking along a line marked out by cold water. Ample evidence, during the excavations, of this method of destruction was recovered in the form of the blackened sides of pits dug beneath the prostrate stones, burnt fragments of sarsen, and even piles of charred straw. No more vivid representation of the whole process can be imagined than a spirited drawing by Dr Stukeley (FIG. 12), hitherto unpublished, and obviously the work of an eye-witness.

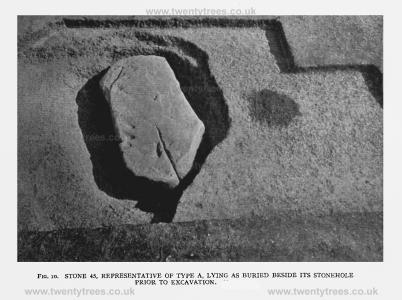

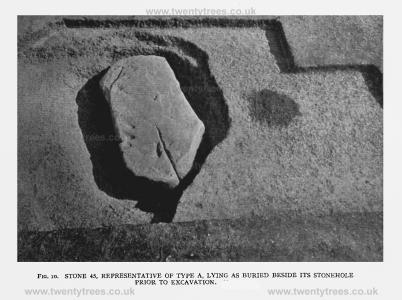

Presumably about the same time or at a somewhat earlier date farmers, in order to facilitate ploughing, buried certain of the stones where they lay. The existence of these had in the meantime been forgotten but they were uncovered during the excavations, and together with all stones still lying on the surface were re-erected in their original stoneholes (FIG. 10).

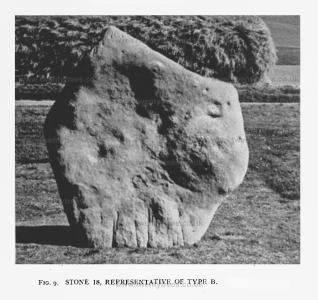

The stones of the monument of Avebury have hitherto been erroneously referred to as 'rough unhewn blocks of sarsen'. Actually these megaliths have been dressed, and very carefully dressed, although not, it should be noted, to the flat surface obtained at Stonehenge. Moreover there can be no question but that the stones were dressed deliberately to conform to certain required shapes, and to this end stones were in the first place selected as near to the required form as possible, with a resultant economy in the labour of the final dressing. Space forbids a detailed discussion here on the question of the shapes to which the stones were formed, and it will suffice to say that these may be divided into two main types, which may be termed type A and type B, each retaining certain apparently essential features in every example. Broadly speaking type A (FIG. 10) takes the form of a tall stone considerably higher than it is broad, while type B (FIG. 9) is broader in proportion to its height, the most distinct examples resembling to a certain extent an asymmetrical diamond in shape.5 A well-contrasted pair actually face each other in the avenue, nos. 49 and 50. As regards size, this would not appear to have been a matter of great significance to the original builders, since even stones next each other often provide a startling contrast in this respect, although pairs of stones in the avenue compare closely the one to the other in height.

Note 5. It is significant that stones have since been recognized to have been dressed to these forms in stone circles as far apart as Cornwall and Cumberland.

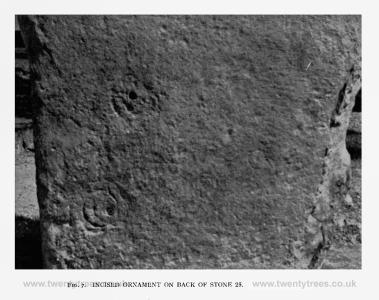

Two stones, and possibly a third, were found to bear ornament of ‘cup and ring’ type-circles made in ‘pocked’ technique (no. 2 of Burkitt’s sequence of Irish techniques in IPEK, 1926, 52) usually but not invariably surrounding a central spot. Two well-preserved examples (FIG. 7) show irregular double concentric circles surrounding a pair of depressions, of which in each instance one is a natural hole in the sarsen and the other artificially worked. Such ornament is well-known in Early Bronze Age contexts in north Britain, but hitherto it has not been recognized from southern megaliths.

From the outset it had, as has been said, been the hope of the excavators that evidence bearing on the date of the avenue might be obtained, and this hope was fulfilled beyond expectation, for such evidence proved to be abundant and consistent.

The first clue to the culture and date of the construction of the avenue was afforded by the fact that a habitation-site was found around stones 11 to 20. Structurally, nothing was present but a number of hearths or fire-pits and two rubbish-pits, with no indication of huts or other structures. Over the whole area occurred numerous potsherds uniformly of Neolithic B types, and a very individual flint industry, characterized by the presence of 'petit tranchet derivatives' of all forms, and knives and scrapers with polished edges recalling that from the West Kennet long barrow. Fragments of two axes of the augitegranophyre of Graig Lwyd were found, and an arrowhead of Portland Chert. The most striking find of imported stone was however two fragments of Niedermendig lava, from the Andernach region of the Lower Rhine, which rock had previously been found in an Early Bronze Age context by Mrs Cunnington at 'The Sanctuary'.6

Note 6. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XLV, 332.

In the rubbish-pits were found numerous animal bones, and sherds with cordons recalling certain members of the 'groove-ware' family (e.g., Sutton Courtenay). In the upper part of pit I was found a fragment of the base of a beaker identical with that from the burial by stone 25, and it seems probable that the absence of beaker elsewhere in the habitation-site may be a cultural rather than a strictly chronological distinction. There can, we think, be little doubt that the habitation-site antedated the construction of the avenue across it, but the difference in time need not have been more than a matter of a year or so. In the Avebury region it is almost impossible to regard the Neolithic B and Beaker cultures as other than broadly contemporary, but the two groups of people may well have lived side by side without cultural interchange.

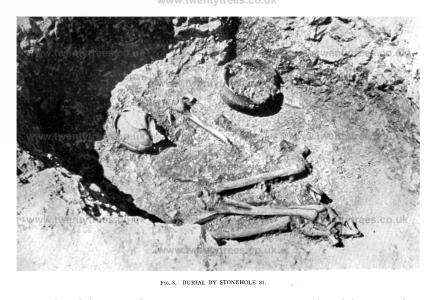

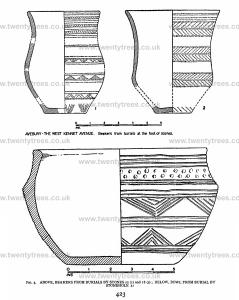

More precise evidence of date however was found in the form of burials at the foot of stones. Four such burials were found, against stones 18, 25, and 39, and beside stonehole 31 (FIG. 8). With the first two, beakers of type B were found (FIG. 3). The burial by stone 39 had no grave-goods, but that by stonehole 3 I was accompanied by a remarkable bowl (FIG. 3) which is without precise parallel, although certain handled vessels from Dorset and the Isle of Wight seem to offer the best analogues.7

Note 7. cf. Proc. Prehist. SOC., 1935, 147

It is a noteworthy fact that all four burials were placed on the northeast of their particular stones, that is to say, while the burials beside stones 25 and 39, and stonehole 31, were on the inner side as regards the avenue, that beside stone 18 was on the outer side. The graves beside numbers 18, 31, and 39 were separated by a short distance from the stoneholes themselves, and although strong presumptive evidence would exist for their contemporaneity with the construction of the avenue, it would have been possible, however improbable, for these burials to have taken place after, or even before, the erection of the stones. Not so the burial by stone 25, however, since in this case the grave actually formed part of the stonehole itself, and there is adequate evidence that the burial had taken place after the erection of the stone, but while it was artificially supported in its position and before the filling of the stonehole together with the packing stones had been forced into position, a proceeding which, incidentally, had been responsible for some degree of damage, through crushing, to the skull.

This association of beaker burials with stones of the avenue at Avebury is in accordance with the evidence previously recorded from the Longstones near Beckhampton8 and at 'The Sanctuary',9 where in each case a burial with a B beaker was found against a stone.

Note 8. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XXXVIII, 5.

Note 9. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XLV, 313.

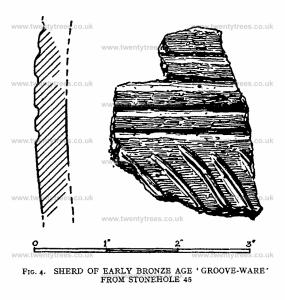

In addition to these burials, ritual deposits of flint flakes and other implements, and animal bones, were found in several stoneholes-a practice which has parallels in Brittany.10 The most important object found in such a deposit was a sherd of Early Bronze Age 'groove-ware', of the type to which the Woodhenge pottery belongs (FIG. 4). This occurred in association with animal bones and flint flakes in stonehole 45. Scraps of beaker were found in two stoneholes, nos. 9 and 52, while in stonehole 67 was found the upper part of a small bowl of burnished reddish-brown ware, with an everted lip and shoulder in an almost Iron Age style. We can suggest no significant parallel to this remarkable vessel. The accompanying table (page 427) shows the incidence of finds associated with the stones. Apart from those already described, an axe of foreign stone from stonehole 13 and the arrowhead fragment of olivine dolerite from stonehole 66 should be noted.

Note 10. du Chatellier, Les Epoques Prkhistoriques dans le Finistdre 26.

This evidence of date from the avenue is in accordance with that from the Circle itself, where the fragment of Neolithic B ware found by Mr Gray beneath the vallum,11 and the ‘petit tranchet derivative’ found similarly on the surface in Sir Henry Meux’ trench,12point to a date in the Early Bronze Age. During the excavations of 1935, a most interesting link between the building of the avenue and the digging of the great ditch was provided by the occurrence of packing-blocks of Lower Chalk in stonehole 57. As has been said, the Avebury monument stands on Middle Chalk, but the depth to which the ditch was dug makes it geologically probable that Lower Chalk must have been reached at certain points. It is consequently a reasonable presumption that it was from this material dug from the lower levels of the great ditch that the packing material in stonehole 57 was obtained. Assuming that the stones of the Circles must have been brought into position before the barrier of bank and ditch was made, and since we now see that in all probability the avenue was being constructed at the same time as this ditch was being dug, an interesting sequence of construction is provided.

Note 11. Archaeologia, LXXXIV, 137 and 140.

Note 12. Wilts. Arch. Mag., XLVII, 288-9.

Quite unexpected Iight was thrown on the state of the avenue in later prehistoric periods by the presence in the vicinity of stones I to 8 of a curious flint industry, almost certainly of the Early Iron Age, and contrasting very strongly both in workmanship and patination with the Late Neolithic series from the habitation-site mentioned above. Of these stones six were still in existence, although all lay prone on the ground, and it was found on excavating the stoneholes that the upper layers of several of them contained the typical debris of flint working, which was also abundant in the immediate neighbourhood. On the other hand, such debris was not discovered under any of the stones themselves when these were raised during the course of re-erection, thus proving that the stones had fallen prior to Early Iron Age times. It is to be presumed that the hollows of the stoneholes, which at that period had not been silted up or ploughed level with the surrounding surface, formed convenient rubbish-pits for flint-knappers, and were consequently so used. Indeed, in one instance, that of no. I, where the stone, which had an attenuated base and a disproportionately heavy top, had fallen over its own stonehole, the flint-knapper had actually dug a shallow pit at the foot of the stone corresponding to the usual position at which a stonehole was found-indeed, it strongly resembled one-and this he filled with his discarded flakes.

As the avenue proceeded up the slight hill towards Avebury, it was found that its course was crossed transversely by field boundaries that survived as 'negative lynchets', and which had obviously formed part of the extensive field-systems of the Early Iron Age and Roman periods that cover the slopes of the downs in the neighbourhood. We see therefore that, unlike Stonehenge, Avebury’s significance and sanctity had been forgotten by the Early Iron Age. In fact the contemporaries of the Druids, so far from watching stately processions of mistletoe-bedizened, white-robed priests winding along the avenue, were ploughing cornfields across its line and chipping flints in the lee of its unconsidered fallen stones.

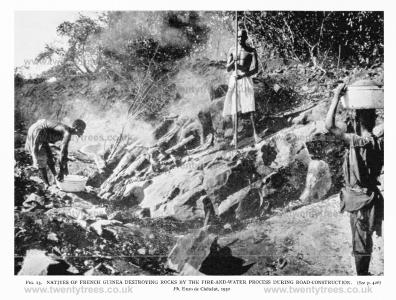

We have added an illustration to show the modern practice of destroying rock-surfaces by fire and water. This method is still in use in French Guinea. The photograph reproduced here (FIG. 13) was taken by Mrs Enzo de Chktelat in November 19-32, near Pita on the Fouta-Djallon plateau. It depicts the construction of a road by Foulah workmen, under the direction of the French ‘Commandant-de-Cercle'. The rocks are diabase covered by laterite. EDITOR.