Europe, British Isles, South-West England, Wiltshire, Avebury Henge and Stones, Long Stones Cove aka Devil's Quoits [Map]

Long Stones Cove aka Devil's Quoits is in Avebury Henge and Stones [Map], Avebury Type Cove, Avebury Late Neolithic Early Bronze Age, Beckhampton Avenue.

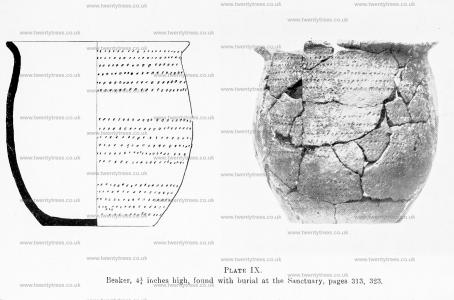

Long Stones Cove aka Devil's Quoits [Map], aka Adam and Eve, Longstone Cove, Devil's Coits, describe two large upright sarsen stones in a field to the south-west of the Avebury Henge. One of the stones fell and was re-erected in 1911. During the course of its re-erection husband and wife Benjamin and Maud Cunnington discovered a crouched skeleton with beaker ware at its foot.

Itinerarium Antonini Augusti aka Antonine Itinerary. Kennet

CUNETIONE. ad fontes fluvii Cunetîonis (Kennett) stat oppidum ejusdem nominis. Vicina regio tota scatet Castrorum & Tumulorum reliquiis. Aubury & Silbury taceo utpote incertæ originis opera: sed ad collem quem vocant Martinsall hill fese prodit vallum, quod & forma quadrata, & Constantini nummus non ita pridem erutus, Romanum fuiise arguit. Ager etiam vicinus oftendit tres lapides pyramidales, Hermis illis Isurianis prorfus similes, quos Devils Coits. de vulgus Diabolo attribuit suo nomine Discorum Diabolicorum.

CUNETIO. at the sources of the river Cunetion (Kennett) stands a town of the same name. The whole neighborhood abounds with the remains of Castles and Mounds. I omit Aubury and Silbury, as they are works of uncertain origin: but at the hill which they call Martinsall hill, a rampart protrudes, which, with its square form, and a coin of Constantine unearthed not so long ago, argues that it was Roman. The neighboring field also bears three pyramidal stones, similar to those prostrate Hermes of the Isurians, whom the Devils Coits [Map]. The common people attribute the Devil to his name of Diabolic Discs.

Avebury by William Stukeley. The king-barrows which are round, both here and elsewhere vary in their turn and shape, as well as magnitude, as we see in a group together; whereof still very many are left, many destroyed by the plough. Some of the royal barrows are extremely old, being broad and flat, as if sunk into the ground with age. There is one near Longstone cove [Map] set round with stones. I have depicted two groups of them, one by the serpent's head, on Overton-hill; another by the serpent's tail, in the way between Bekamton and Oldbury camp: some flat, some campani-form, some ditched about, some not. One near the temple on Overton-hill was quite levelled for ploughing anno 1720; a man's bones were found within a bed of great stones, forming a kind of arch. Several beads of amber long and round, as big as one's thumb end, were taken from it, and several enameled British beads of glass: I got some of them, white in colour, some were green. They commonly reported the bones to be larger than common. So Virgil Georg. 1.

Grandiaque effossis mirabitur ossa sepulchris [The bones in the graves will be marveled at by the great digs].

Avebury by William Stukeley. A description of the other great avenue from Bekamton, a mile off, which is the hinderpart of the snake, proceeding from the circle. The cove [Map] on the midway of it called Longstones, or the Devil's coits. The avenue terminated in a valley. Some animal bones found in a stone, whence a conjecture concerning their age. Of the number of the stones. Solomon's temple compared with ours. The mechanicks of the Druids called magick. Of the effect of the weather upon the stones.

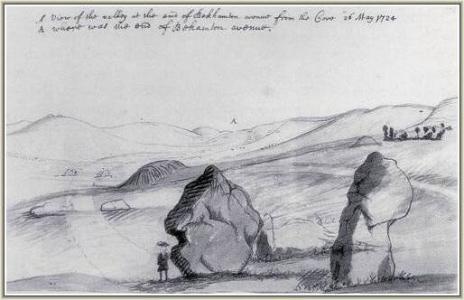

Avebury by William Stukeley. 1724. This Longstone cove [Map], vulgarly called long stones, is properly a cove, as the old Britons called 'em, composed of three stones, like that most magnificent one we described, in the center of the northern temple at Abury; behind the inn. They are set upon the ark of a circle, regarding each other with an obtuse angle. This is set on the north side of the avenue; one of the stones of that side makes the back of the cove. This is the only particularity in which this avenue differs from the former. I take it to be chiefly a judicious affectation of variety, and served as a sacellum or proseucha to the neighbourhood on ordinary days of devotion, viz. the sabbath-days. For if the Druids came hither in Abraham's time, and were disciples of his, as it appears to me; we cannot doubt of their observance of the sabbath. It stands on the midway of the length of the avenue, being the fiftieth stone. This opens to the south-east, as that of the northern temple to the north-east. 'Tis placed upon an eminence, the highest ground which the avenue passes over: these are called Longstone-fields from it. You have a good prospect hence, seeing Abury toward which the ground descends to the brook: Overton-hill, Silbury, Bekamton; and a fine country all around. Many stones by the way are just buried under the surface of the earth. Many lie in the balks and meres, and many fragments are removed, to make boundaries for the fields; but more whole ones have been burnt to build withal, within every body's memory. One stone still remains standing, near Longstone cove.

Longstone cove, because standing in the open fields, between the Caln road and that to the Bath, is more talked of by the people of this country, than the larger, and more numerous in Abury town. Dr. Musgrave mentions it in his Belgium Britannicum, page 44. and in his map thereof.

Mr. Aubury in his manuscript observations published with Mr. Camden's Britannia, speaks of them by the name of the Devil's coits. Three huge stones then standing. It was really a grand and noble work. The stone left standing is 16 feet high, as many broad, 3½ thick. The back stone is fallen flat on the ground, of like dimension.

annis solvit sublapsa vetustas [in years he paid off the old age which had fallen away]:

Fertur in abruptum magnus mons [He is carried on a steep mountain] Virg. Æn. 12.

Avebury by William Stukeley. 1724. By Bekamton cove [Map] another, a vast body of earth, as thick as the vallum of Abury, and points to the cove hard by; which shews that cove to be as a chapel. Another large round barrow near it.

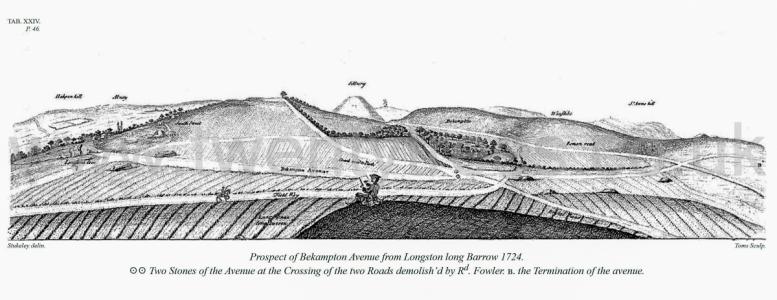

Avebury by William Stukeley. 1724. Table XXIV. Prospect of Bekampton Avenue from Longston long Barrow [Map] 1724. Two Stones of the Avenue at the Crossing of the two Roads demolished by Rd. Fowler. b. the Termination of the avenue.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1857 V4 Pages 307-363. [1730]. From the discursive account of Twining, in which there is much that is altogether irrelevant, all that bears on the actual condition of Abury and its precincts, as observed by him in 1723, five years after Dr. Stukeley's first visit, is here introduced in his own words.

"I take Avebury to have been a temple to Terminus; and that Mr. Cambden meeting with some such tradition, was inclined to think Selborough a boundary, as he doth in his Britannia, (§ 10,14). At Avebury (itself) with its many inward circles of stones (§ 14) the solemnities began and concluded. The circular entrenchment so contrived that the vulgar from thence might view the ceremonies without breaking in on those that officiated (§ 14). Hence they marched with ceremony along the double range of stones for a mile in length, even to the eminence overlooking East Kennet; then halted at the two circles of stones one within another, standing not long since entire. Some remains of the greater circle are yet to be seen (§ 11). The inhabitants have a tradition this was once a place of worship, as I verily believe it; the Romans here keeping their Feralia, in memory of their dead friends, they crowned the stones with garlands and made their offerings to the Manes (§ 12). Then followed the Ludi Funebres in the small plain Selboroughhill stands in; whither by turning to the right, the other range of stones that helps form the Cuwneus (Cunetium, Kennet § 49, 50) conducted them cross the current to a place by nature so fitted to the purpose, (§ 12). Though the neighbouring "Backhampton" is but a small village, its name seems to discover somewhat of the extent and use of the Circus (the whole Cwnetium, as he terms it, he defines as a Circus Lapideus, of between three and four miles1) whether we say that it stood on the back of the Circus, or that they returned this way back in procession (§34). To the oblong part of the Circus this village joins, the Romans, I conceive, gave the name of Discus, in our language a coit, one of the exercises here used. Hence the large stones to the west, the remains of the Discus now standing, are still called the "Devil's Coits [Map]'? (Gale's Iter, p. 135). Not that these two stones were ever British Deities, as some learned men have fancied, but a part of the Discus, as other stones lying in the same field do shew, to justify the figure I have assigned the whole" (§ 36).

Note 1. He insists on the river Kennet "" rising within the work," and so shows it in his plan, though it really rises some miles farther north in the winter bourns, giving their names to the villages so called.

Note 2. The stones called the "Devil's Arrows [Map]" at Boroughbridge, Yorkshire, doubtless derive their name in the same way as these.

Colt Hoare 1812. Plate XV. The view (No. 1.) is taken from the vicinity of a very fine bell-shaped barrow, on Hackpen hill, from whence you look down upon Abury, and may distinguish on the left side of the view the most entire part of the Kennet avenue.

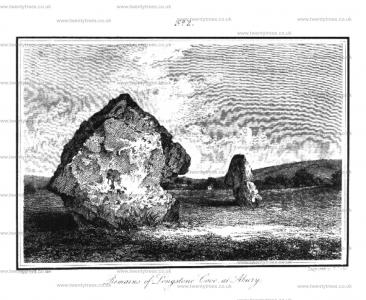

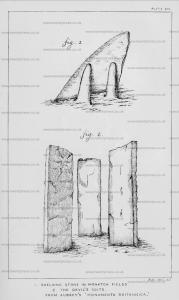

No. 2. represents the only two stones remaining of Longstone Cove [Map], with the village of Abury behind them.

Colt Hoare 1812. Having now, according to the words of Stukeley, "conducted one half, the forepart of the Snake, in this mighty work, up to Overton hill, where it reposed its bulky head, and not long ago, made a most beautiful appearance," shall proceed towards that part of the Snake which designated the tail, and which has been distinguished by the title of Beckhampton Avenue, and investigated by the same learned author in the year 1722.

"Beckhampton Avenue goes out of Abury town at the west point, and proceeds by the south side of the church-yard. Two stones lie by the parsonage gate on the right hand; those opposite to them, on the left hand, in a pasture, were taken away in 1702, as marked in the ground plan of Abury. Reuben Horsal remembers three standing in the pasture. One now lies in the floor of a house in the church-yard. A little farther, one lies at the corner of the next house on the right hand, by the lane turning off to the right to the bridge. Another was broke in pieces to build that house with, in 1714; two more lie on the left hand opposite. It then passes the beck south of the bridge. Most of the stones hereabouts have been made use of about the bridge, and the causeway leading to it. Now the avenue passes along a lane to the left hand of the Caln road, by a stone house called Goldsmith's farm, and so through farmer Griffn's yard, through one barn that stands across the avenue, then by another which stands on its direction. Two stones and their opposites still lie in the foundation: immediately after this, it enters the open ploughed fields, the Caln road running all this while north of it. If we look back, and observe the bearings of Abury steeple, and other objects, a discerning eye finds, that it makes a great sweep, or curve the avenue entering the open corn fields, runs for some time by the hedge on the right hand. When it has crossed the way leading from South-street, we discem here and there the remains of it, in its road to Longstone Cove [Map]. Farmer Griffin broke near twenty of the Stones belonging to this part of the avenue.

Colt Hoare 1812. 1812. To the Beckhampton avenue there appears formerly to have been an appendage, called Longstone Cove [Map], of which Dr. Stukeley has given the following account. "This Longstone Cove, vulgarly called Longstones, is properly a Cove, as the old Britons called them, composed of three stones, Like the most magnificent one we described in the centre of the Northern temple at Abury. "They are set upon the ark of a circle, regarding each other with an obtuse angle. This is set on the north side of the avenue: one of the stones of that side makes the back of the Cove. This is the only particularity in which this avenue differs from the former. I take it to be chiefly a judicious affectation of variety, and served as to the neighbourhood on ordinary days of devotion. It stands on the midway of the length of the avenue, being the fiftieth stone. This opens to the south-east, as that of the northern temple to the north-east. It is placed upon an eminence, the highest ground which the avenue passes over. These are called Longstone fields from it. Longstone Cove, because standing in the open fields between the Caln road and that to Bath, is more talked of by the people of this country than the larger temple in Abury town.

Mr. Aubrey, in his Monumenta Britannica, thus mentions this fragment of antiquity. "Southward fram Aubury in the ploughed field, doe stand three huge upright stones, perpendicularly, like the three stones at Aubury: they are called "The Devill's Coytes [Map]," In the rude sketch he has givens he delineates them as placed angularly, like those which form the cove of the Northern temple at Abury. Two of the three stones that formed this cove [Map] still remain, and are delineated in one of the engravings annexed to this work, Plate XV, No. 2.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1857 V4 Pages 307-363. The two large stones [Long Stones Cove aka Devil's Quoits [Map]] near the Long barrow [Map] stand "on the midway of the length of the avenue," and are "placed upon an eminence, the highest ground which the avenue passes over." One of these stones set upon the arc of a circle at an obtuse angle with two others, which have disappeared, formed a cove resembling that in the centre of the northern temple at Abury, of which Aubrey has preserved a sketch. The stone now standing is 16 feet high, as many broad, and 3½ thick, and formed the eastern jamb of the cove. The back stone, of like dimension, which was lying on the ground when Stukeley wrote, has been removed many years; while the third was carried away by Richard Fowler when Stukeley was at Abury. Aubrey, in his 'Monumenta Britannica,' thus speaks of the stones he saw at this spot; "Southward from Aubury in the ploughed field, doe stand three huge upright stones, perpendicularly, like the three stones at Aubury; they are called the Devill's Coytes." (See plate viii. 2.1) Dr. Musgrave speaks of them as 'Diaboli Disci,' and says that Dr. Gale considered them to have been Belgic Herme.2 Of the stones which formed the part of the avenue between Abury and this cove, Stukeley says, "Many stones by the way are just buried under the surface of the earth. Many lie in the balks and meres, and many fragments are remov'd to make boundaries for the fields; but more whole ones have been burnt to build withal, within every body's memory. One stone still remains standing, near Longstone Cove."3 Describing the course of the ayenue from the cove towards its end, he says, "The avenue continu'd its journey by the corn-fields. Three stones lie still by the field-road coming from South street to the Caln road. Mr. Alexander told me he remember'd several stones standing by the parting of the roads under Bekamton, demolish'd by Richard Fowler. Then it descends by the road to Cherill, till it comes to the Bath road, close by the Roman road, and there in the low valley it terminates, near a fine group of barrows, under Cherill-hill, in the way to Oldbury-camp; this is west of Bekamton village.".... "In this very point only you can see the temple on Overton Hill [Map], on the south side of Silbury Hill. Here I am sufficiently satisfied this avenue terminated, at the like distance from Abury-town, as Overton Hill was, in the former avenue; 100 stones on a side, 6000 cubits in length, ten stadia or the eastern mile. Several stones are left dispersedly on banks and meres of the lands. One great stone belonging to this end of the avenue, lies buried almost under ground, in the plow'd land between the barrow west of Longstone long barrow, and the last hedge in the town of Bekamton. Richard Fowler shew'd me the ground here, whence he took several stones and demolish'd them. I am equally satisfied there was no temple or circle of stones at thisendofit".... Had there been, "it would most assuredly have been well known, because every stone was demolish'd within memory when I was there. I apprehend this end of the avenue drew narrower in imitation of the tail of a snake, and that one stone stood in the middle of the end, by way of close."4

Note 1. Aubrey's sketch gives the position, not the form of these stones. For a representation of the remaining one, see Hoare's 'Ancient Wilts,' ii. pl. xv. f. 2.

Note 2. "De lapidibus altis immense magnitudinis quos Diaboli Discos appellat vulgus, plurime sunt conjecture, quarum unam alibi tangam." Musgrave's 'Belgium Britannicum,' vol. i. p. 44, 1719. "Sed ut hanc rem extra dubium ponam doctissimus Galzeus, in explicandis veterum monumentis cum primis sagax, Agro Cunetioni vicino (est illud oppidulum Belgii) tres lapides pyramidales esse tradit, quos Hermas esse non sine ratione judicat, iisque non absimiles, quos propeIsurium (Aldborough) inventos ere insculpi fecit. Tres erant hujusmodi lapides in hoe agro, ut in Isuriano, et forte ad eundem usum nempe viam commonstrandam, unde Mercurius dicebatur ενόδιος." Ibid, p. 111.

Of the high stones of immense size, which the common people call the Devil's Discs, there are many conjectures, one of which I shall touch upon elsewhere.

But in order to put this matter beyond doubt, the most learned Galzeus, with the first skill in explaining ancient monuments, reports that in Agro Cunetion (that is a small town in Belgium) there are three pyramidal stones, which he judges not without reason to be Hermas, and not unlike those which are near Isuria (Aldborough). He made the finds to be engraved. There were three stones of this kind in this field, as in the Isurian, and perhaps for the same use, that is to say, to mark the way, whence Mercury was said to be single.

Note 3. This stone, the solitary remnant of the Beckhampton avenue, is still standing (1857). It is shown to the N. of the Cove Stone in the large ground plan, and it is figured in 'Ancient Wilts,' ii. pl. xv. 2.

Note 4. Stukeley's Abury, pp. 34, 35, 36, and plates i., xxiv., and xxv,

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1878 V17 Pages 327-335. The Beckhampton avenue was also visible, though not so perfect as the other, in the memory of the late Mr. John Clements1 (aged eighty-one at the time of his death), who could clearly point it out. This had been chiefly demolished by Farmer Griffin, and Richard Fowler. The two stones in the cove [Map]2 are all that now remain, and with diffculty they were saved by applying from the farmer to the landlord. Mr. John Brown is now the owner of this estate."

Stukeley's account of this latter avenue derives not unimportant confirmation from these recollections of the "ancient Clements," who probably in his boyhood was an eyewitness of Dr. Stukeley's surveys.

Note 1. John Clements was a grocer in Abury aud born in 1714. The two hundred years, from John Aubrey's early visits to the present time, are bridged over by the lives of three persons residing at or near Abury, viz., "Parson Brunsdon," John Clements, and the Rev. Charles Lucas.

Note 2. The lesser and more northern of these stones did not belong to the cove.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1879 V18 Pages 377-383. Thus, Mr. Jackson writes (p. 325), "of a stone avenue leading from Abury to Beckhampton (which is the great point in dispute) Aubrey says not one word. He mentions the three gigantic blocks of stone called ‘The Devil’s Coits [Map],’ (now the Long Stones [Map]) which lay on that side of Abury and of which two are still left standing ; but no other, great or small, standing upright anywhere near them. If on that side of Abury there were any not upright, but lying about or half-buried in the ground, it is clear that they did not attract his eye as stones that had ever formed part of the general structure. Stukeley’s statement, on the other hand, is that coming out of the earthwork on the road towards Beckhampton he saw stones, some lying in the very road, some in the pastures; and that he was told of others that had been broken up in the fields all within a few years prior to 1722. Upon what certainly must be called very slender evidence, he created an avenue of two hundred stones running some way beyond Beckhampton and ending in a point upon the open downs .... The narrowing of the latter part of this supposed avenue, and its ending in a point, are admitted by Stukeley himself to be only a supposition .... The end of the Beckhampton avenue being fanciful, it is not impossible that the same fancy may also have been at work in constructing other parts of it."

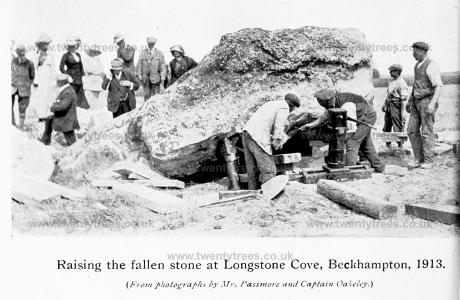

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1913 V38 Pages 1-11. Between 8 and 9 o'clock on the morning of December 2nd, 1911, one of the standing stones at Avebury fell. The stone is one of the two remaining stones of the three which are believed to have once formed a kind of cell, or cove, on the northern side of the Beckhampton, or western avenue, that issued from the great circle of Avebury. The third stone fell and was broken up many years ago. The group was known as "Longstone Cove [Map]," or the "Long- stones," but the two remaining stones are now sometimes spoken of locally as " Adam and Eve." The cove is described by Stukeley2 as consisting of two stones set at an angle to each other outside the avenue, the other stone that Stukeley regarded as the third member of the cove group, being at the same time one of the stones of the avenue. This latter stone is the smaller of the two now remaining, known as "Eve"; the larger one, "Adam," which fell in 1911, being one of the two original outstanding stones of the cove.

Note 1. These notes, so far as they relate to the discovery of the skeleton and drinking cup, were printed in Man, Vol. xii., No. 12, Dec, 1912, pp. 200 — 203, and the Society is indebted to the Council of the Royal Anthropological Institute for the loan of the two blocks which illustrate the paper.

Note 2. The Rev. W. C. Lukis, in a report on Stonehenge and Abury, printed in Proc. Soc. Ant., IX., 131, says (p. 155) of the Longtones Cove, "Stukeley says this cove is 'composed of three stones like that most magnificent one we described in the centre of the northern temple at Abury [Map]. They are set upon the arc of a circle regarding each other, with an obtuse angle,' and are placed on the north side of the avenue, one of the stones of that side making the back of the Cove.... Twining saw two stones only in 1723, therefore Stukeley saw no more; and his knowledge of a third stone must be derived from Aubrey, whose sketch given in his 'Monumenta Britannica' shows how unfaithful his drawings are as to the form and position of the stones. It is altogether an assumption on Stukeley's part that one of the stones of the Cove was one of the supposed avenue.... My own opinion is that these stones are the remains of a large circle — a monument entirely distinct from Avebury."

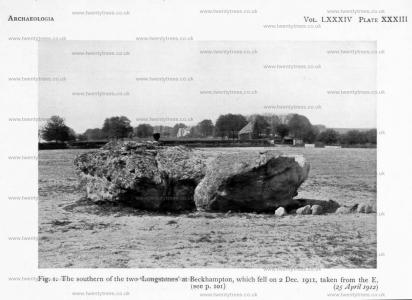

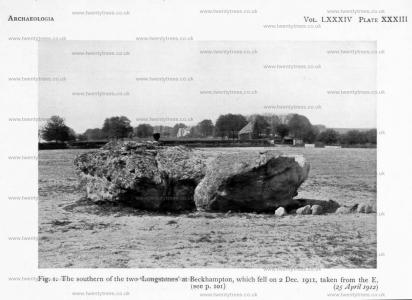

Archaeologia Volume 84 1935 Section VI. 25 Apr 1912. Plate XXXIII. Fig. 1. The southern of the two ‘Longstones [Map]’ at Beckhampton, which fell on 2 Dec. 1911, taken from the E.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1913 V38 Pages 1-11. Jun 1913. The Re-Erection of Two Fallen Stones [Long Stones Cove aka Devil's Quoits [Map]], and Discovery of an Interment with Drinking Cup, At Avebury.1 By Mrs. M. E. Cunnington (age 43).

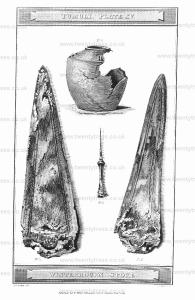

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1930 V45 Pages 300-335. PLATE IX.

Photograph and drawing of the beaker found in front, and just below the knees, of the skeleton in the burial close to the inner side of the stone hole 12, in the inner stone circle. Height 4½in., rim diam, 4in., base 2½in. Paste black and sparingly mixed with particles of flint, surface dull brown, rim; out-bent. Ornamented with horizontal rows of small punch marks arranged in three groups with plain zones between, six rows in the two upper groups and five in the lower.

The vessel approximates to type B, i.e. ovoid cup with recurved rim. Of the beakers illustrated by Abercromby No. 42 bis, from Stoford, Somerset, is nearest to it with regard to the punch mark decoration.1

It may be remembered that a skeleton burial with a beaker was found close to the foot of the stone "Adam [Map]," at Beckhampton, when it fell in 1911.2

Note 1. Bronze Age Pottery, vol. 1.

Note 2. W.A.M., vol. xxxviii., 1.

Archaeologia Volume 84 1935 Section VI. Proceeding round to the WSW., at a distance of nearly a mile from the centre of Avebury, we come to the ‘Longstone Cove [Map]’, ‘Longstones [Map]’, or ‘Devils Quoits [Map]’. Aubrey spoke of three upright stones, but two only remained in Stukeley’s time. They are now known as ‘Adam’ and ‘Eve ’, and stand about 95 ft. apart. At the end of 1911 ‘Adam’ fell, and when the Wiltshire Archaeological Society re-erected it a human skeleton and beaker, both in a fragmentary condition, were found, which must have been buried after the original erection of the stone. Some of the packing-stones are seen in the photograph of the monolith (pl. xxxiii, fig. 1); with them part of another beaker was found. The length of the stone was 17¾ ft., maximum width 15 ft. 4 in.; estimated weight, 62 tons.1

Note 1. Wilts. Arch. Mag. xxxviii, 1-11.

Antiquity 1936 Volume 10 Issue 40 Pages 417-427. A second avenue, ‘The Beckhampton Avenue’, has sometimes been claimed to have run to the Avebury circles from the southwest, where two stones, ‘The Longstones [Map]’, stand, and were considered by Stukeley to be part of such an avenue. In the writers’ opinion, however, it seems more likely that, as originally suggested by Schuchhardt many years ago,1 the Beckhampton standing stones represent the remains of an independent stone circle with an avenue, of which Stukeley saw the remains, running from it towards the Kennet. It seems very improbable that an avenue to the Avebury Circles should have crossed the river as the assumed Beckhampton course would make it do, and the suggested interpretation has parallels at Stanton Drew, and, indeed, at Stonehenge itself.

Note 1. Prähistorisch Zeitschrift, 1910, II, 315.