Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1930 V45 Pages 300-335

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1930 V45 Pages 300-335 is in Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1930 V45.

The "Sanctuary" [Map] On Overton Hill, Near Avebury. By M. E. Cunnington (age 60). Being an account of excavations carried out by Mr. and Mrs. B. H, Cunnington in 1930.

The earliest known description of the circles of standing stones at Avebury and on Overton Hill is that of Aubrey in the 17th century. His account of the rings on Overton Hill is very brief, but he left a plan giving further details (Plate IV.). He says "above which place (i.e. West Kennet) on the brow of the hill, is another monument, encompassed with a circular trench, and a double circle of stones, four or five foot high, tho’ most of them are now fallen down."1

Note 1. Gibson’s Camden (1695), 111—112; quoted by Stukeley in Abury, 32; see also Jackson’s Aubrey, 322; W.A.M., iv., 317. Aubrey's Monumenta Britannica, the MS. of which is now in the Bodleian Library, has never been published in full, but extracts relating to Wiltshire, with reproductions of the two plans referred to, will be found in Jackson’s Aubrey, published by the society in 1862, and in Long’s Abury, W.A.M., iv., 310 (1858); vii. 224.

Aubrey first saw Avebury in 16481 but his account does not seem to have been written till between the years 1659—1670.2

Note 1. W.A.M,, iv., 311

Note 2. Jackson’s Aubrey, ii.

Under date June 15th, 1668, Pepys in his Diary, after describing his visit to Avebury, writes "So took coach again, seeing one place with great high stones pitched round, which, I believe, was once some particular building, in some measure like that of Stonehenge. But, about a mile off, it was prodigious to see how full the Downes are of great stones; and all along the vallies stones of considerable bigness." Pepys was going from Avebury to Marlborough, so the circles on Overton Hill seem to be the only site to which this description of a place, reminding him of Stonehenge, could apply. If this is so, this mention of the circles is second only to that of Aubrey.

The next description that we have of Avebury and its environs is that of Dr. Stukeley, written some fifty or sixty years later. Dr. Stukeley visited Avebury in several successive years before and after 1720, but his book Abury was not published till 1743.

He made a detailed study of Avebury and its surroundings, and his observations, though not always very accurate, are invaluable. Stukeley was influenced by the idea of serpent worship, and thought that Avebury was laid out to represent a great serpent.

The circles at Avebury itself represented the coiled body; a double row of standing stones that Stukeley thought ran westwards (the problematical Beckhampton avenue) represented the tail, and the Kennet avenue the forepart of the body, while the circles on Overton Hill, at which the Kennet avenue ended, were regarded as the head.

Stukeley describes with feelings of lively regret how what still remained of these circles on Overton Hill were destroyed in the winter of 1724, in order to clear the ground for ploughing and "to gain a little dirty profit." They (i.e. the country people) still call it the Sanctuary."1

Note 1. Abury, 31. This does not seem a name at all likely to have been given by the local country folk. Aubrey made a marginal note in his M.S. to ask the name of the rings, but unfortunately, if ever asked, the answer has not come down to us.

The accounts given by Aubrey and Stukeley of the Sanctuary differ very considerably. Aubrey’s sketch shows the rings as circles, while Stukeley describes them as two concentric ovals and plans them as such; he also states that the stones of the inner ring "were somewhat bigger than of the outer ring.1"

Note 1. Abury, 32

Stukeley did not doubt that the Kennet avenue connected the Sanctuary with Avebury, but he says that Aubrey "did not see that ’tis but one avenue from Abury to Overton-hill, having no apprehension of the double curves it makes"1 This suggestion that Aubrey did not realise this connection is scarcely born out by Aubrey’s own words "West Kynet stands in the angle where the walke (i.e. avenue) from Aubury hither, and that from the top of the hill did joine.... and ’tis likely that here might in the old time have been the celle or Convent for the priests belonging to these temples."2 And again in describing the Kennet avenue Aubrey says — "From the south entrance runnes a solemne Walke, sc. of stones pitch’d on end about seven foot high, wch goes as far as Kynet (wch is (at least) a measured mile from Aubury) and from Kynet it turnes a right angle east-ward crossing the river, and ascends up the hill to another monument of the same kind (but less).... very probable this walke was made for processions."3

Note 1. Abury, 32

Note 2. Jackson’s Aubrey, 323.

Note 3. W.A.M., iv., 315—6; Aubrey made a slip in saying the avenue crossed the river Kennet and in his sketch where the river is shown, his drawing of the avenue does not cross it.

When in the Spring of 1930, the possibility of excavating the Sanctuary was being considered, the first difficulty was to locate the site. It was known only that it had stood somewhere in the field once known as Mill Field, west of the Ridgeway and south of the main road (see note 2, p. 317).

By the courtesy of the Archeology Officer of the Ordnance Survey, a number of photographs of the field taken from the air were examined, but none gave any indication of the site of the Sanctuary, though the ditch of the much-ploughed barrow in the same field, and of a barrow, quite invisible on the ground, in the corner just north of the road, west of the Ridgeway, were clearly defined. Attempts were made to locate the site in relation to barrows shown by Aubrey and Stukeley, but it was found impossible to identify these with the barrows still standing (see note 3, page 318).

Eventually it was found that a remark of Stukeley’s that it was possible to see the serpent’s head from its tail, limited the area that need be searched. Describing what he regarded as the end of the Beckhampton avenue, Stukeley says—‘in the low valley it terminates near a fine group of barrows under Cherhill-hill,.... This point facing that group of barrows and looking up the hill is a most solemn and awful place;.... And in this very point only you can see the temple on Overton-hill, on the south side of Silbury-hill.1 The group of barrows is that close to what is now known as Fox Covert [Map], some three-quarters of a mile west of Beckhampton cross roads. On going to this spot it was found that a small triangular patch of Mill Field, 24 miles away, could be seen, and by counting the telegraph poles visible along the roadside, it became easy to define the possible area on which the Sanctuary must have stood.

Note 1. Abury, 36.

Mr. W.J. Osmond, the owner and occupier of the land, having given permission, although the field was already planted with sugar beet, excavations were begun on May 20th, 1930, and continued for five weeks, four men being employed all the time, and for three weeks five men.

A trial trench, 6ft. wide, was dug from the lower limit of the area towards the Ridgeway, roughly parallel with the main road, and on the third day when hopes were running low, two stone holes that proved to belong to the outer ring were found, and the position of the circles thus established, work went on uninteruptedly until all the holes of the two stone circles, and those of the hitherto unsuspected post hole rings, were uncovered.

THE SITUATION

The circles stand on a small level plateau at the south-western end of the spur or ridge of down that runs northwards to Hackpen Hill. The Ridgeway follows along this crest and passes within a few yards of the rings on their eastern side.

The site is like that of Woodhenge [Map] in that a river, the Kennet, flows at the bottom of the ridge less than a quarter of a mile away.

The situation is a beautiful one with extensive views. Through the valley eastwards the Kennet meanders towards Marlborough,with Savernake Forest to the right, and a glimpse of bare downs in the distance. Southward range the highest chalk hills in Wiltshire, with Wansdyke visible along the crest on its way from Savernake to Tan Hill. Westward are the scarp of Roundway Down, and Oldbury or Cherhill Hill [Map], crowned with a fine earthwork. Further to the north Windmill Hill with its barrows can be seen, and the tower of Avebury Church [Map] (when the trees are leafless), but not Avebury itself.

If it were not for some trees and buildings the whole course of the Kennet avenue would be visible, except for a short length of about 150 yards as it approaches the entrance to Avebury, a fold in the down shutting it off, and all of Avebury except for a glimpse of the crest of the bank on the eastern side.

There are some dozen round barrows in sight on the hill itself, and across the river to the south, just above the tiny village of East Kennet, is a broadside view of the East Kennet long barrow [Map] planted with trees.

Further to the west lies the well-known West Kennet long barrow [Map], called by Stukeley "South" barrow. "It stands," he says, ‘east and west pointing to the dragon’s head on Overton-hill"1 Actually, however, its long axis is directed considerably to the south of the Sanctuary.

The upper part of Silbury Hill can be seen. Stukeley said "Silbury-hill answers the avenue directly, as it enters this temple, being full west hence."2 It will be seen (Plate I) that the southern line of stones of the avenue is very nearly directed to Silbury, but that the avenue is not "full west." It must be remembered, however, that the recovered part of the avenue was not planned by Stukeley, and was, therefore, presumably destroyed before his time; the avenue stone nearest to the rings shown on Stukeley’s plan judging by the spacing of the recovered stone holes, must have been the fifth outwards from the rings. Plate IV.

Note 1. Abury, 46.

Note 2. Abury, 33. Again on page 51 Stukeley says "The neck of the snake going down from Overton-hill regards Silbury precisely, and their intent was that it should be full west, but tis ten degrees north of west."

The hill itself is generally known as Overton Hill (as it was in Stukeley’s time), but the site is actually in the parish of Avebury, the Ridgeway being the boundary between that and the parish of West Overton. The hill is also known as Kennet Hill and Five Barrow Hill, and in a 10th century Saxon Charter was named Seven Barrow Hill. (Cod. Dip. No. 571; W.A.M,, vi., 327).

SUMMARY OF RINGS

Note 1. Posts only.

THE TWO STONE CIRCLES

It will be seen from the plan that the stone holes of the outer and inner rings form circles, not ovals as stated by Stukeley.

Outer circle, diameter 130 feet

Inner Circle 45 feet.

Holes in Outer circle 42

Holes in Inner circle 16

Stukeley’s figures are approximately (they are given in "Druid’s" cubits).

Outer ring, diameters 155 feet x 138 feet

Inner ring, diameters 52 feet x 45 feet

Stones in Outer ring 40

Stones in Inner ring 18

Aubrey’s figures are:—

Outer circle 45 paces=40 yards=120 feet

Inner circle 16 paces=15 yards = 45 feet

Stones in Outer circle 22

Stones in Inner circle 15

The difference in the number of the stones between Aubrey and Stukeley may perhaps be accounted for on the supposition that Aubrey counted the stones he saw, while Stukeley estimated the numbers there should have been when the rings were complete.

It will be seen that Stukeley’s figures for the short diameters of his ovals agree fairly closely with those of the actual circles. How Stukeley made the long diameter of the outer ring 25ft. too long (east and west) with two less than the correct number of stones is difficult to understand.

It has been said that there are 42 stone holes in the outer circle, but it will be seen that a small hole shown on the northern side is numbered 7a, and if this is included the holes would number 43. In the stone holes Nos. 7—8 —9, post holes were found penetrating below the level of the bottom of the stone hole, and are therefore in all probability earlier than the erection of ‘the stones. ‘I'he hole 7a, 18 inches deep, oval in shape, measuring only 20 X 16 inches at top, is of the same character as the post holes and not at all like a stone hole and is therefore not included among them. ‘These few post holes may have had some function in common, but what that was, or their relation to the rings, it is not possible to say.

Beyond the outer circle on the eastern side, it will be seen that there are two stone holes, X1 and X2; the significance of these holes is not known, and it is just possible that they are the sites of naturally deposited sarsens that have been removed and broken up in prehistoric, or less probably in comparatively modern times. Originally no doubt many such sarsens were lying in the near neighbourhood of the rings; there are several such stones still apparently an setu only a short distance away on the same ridge north of the main road. At the same time it may be noted for what it is worth that a line drawn from the centre of the circles through the burial at C12, strikes the hole X2, so that it is possible that a stone standing in this hole served as a pointer to the burial place.

As a rule the stone holes lie with their long axis on the circumference of the circles, but in the outer ring there are some apparent exceptions (Nos. 13, 14, 15) which may be due to awkwardly-shaped stones, or to the enlargement of the holes in order to facilitate their over-throw (see note 1, page 317). In nos. 1 and 41, however, the radial position was probably intentional as these two stones were in a line with the avenue and may be regarded as having formed the entrance to it.

It will be seen that there is a stone hole between No. 1 and 41, blocking so to speak, the entrance to the avenue. Both Stukeley’s plan and sketch show that there was no wider gap between the stones at the "entrance" than elsewhere; Aubrey’s sketch-plan also, as far as it may be relied upon, shows the same uniformity of spacing. Plates IV. and V.

THE AVENUE

It will be seen that in addition to the two radially placed holes of the outer circle, three pairs of avenue stone holes were found, and beyond them a fourth pair is shown in dotted lines. The loose rubbly nature of the sub-soil made it difficult in some cases to define the shallow stone holes (see note 4, page 319) and although the fourth pair of holes were sought for in the usual manner, by removing all the top soil in a wide trench, it was not found possible to locate the holes with certainty, so they have been dotted in on plan and are not marked on the ground.

The three pairs of avenue stone holes are on lines radial from the centre. It will be seen that to the north of the avenue are two stone holes (N 1 and N 2), that with No. 3 of the outer circle also form a line that is radial to the centre. Aubrey’s plan shows the stones N 1 and N 2, and a third stone beyond. This latter was searched for but could not be located on account Of the very loose and rubbly nature of the ground. Aubrey shows these three stones as forming the northern side of the avenue and this accounts for the curious bend shown in his plan. He shows these and the three stones on the south side of the avenue all as fallen, and some of the other avenue stones here must have been missing, so to include the stones N 1 and N 2 (and one beyond) as forming part of the avenue it was necessary to assume some twist or bend in the avenue such as he actually shows.

In Stukeley’s plan (Plate IV.) the first pair of avenue stones is shown some 80 feet out from the rings, so it seems that the first four pairs of stones had disappeared before his time, but in the sketch made in 1723 Stukeley shows a single stone lying nearer in, to the north of the avenues and this must be the stone N 1 or N 2. Not seeing its relationship to the rings, perhaps for this reason, Stukeley omitted it from his plan, but as it was in sight, for the sake of accuracy, included it in his sketch (Plate V.).

The holes N 1 and N 2 (anda third seen by Aubrey), apparently show that originally the avenue on Overton Hill, for part of its course at least, consisted of a triple row of stones.

It will be seen that hole 2 on the northern side of the avenue is a peculiar shape, this may be due to faulty digging when the hole was made originally.

THE SIX RINGS OF POST HOLES

(Details of the holes are given on page 322).

Excavation revealed the wholly unexpected fact that, in addition to the two circles of stone holes, there are six rings of holes, concentric with the stone circles, that once held uprights not of stone but of timber (see note 5, page 319).

B. THE FENCE-RING

The outer of the timber circles lies between the outer and inner stone rings, and is exactly half the diameter of the outer one, i.e., 65ft. The holes of this ring are small and shallow and it is suggested that they may have served as supports to a wattle fence; the fact that two holes in the ring (Nos. 33—4) were much deeper and larger than any of the others, and may well have held gate posts, goes some way to support this suggestion.

C.—THE STONE-AND-POST-RING.

The second ring of post holes is on the same circumference as the inner stone circle, stone holes and post holes, alternating without a break all round the circle, 16 of each. These large holes must have held substantial timbers, one well-preserved core (hole 21) measuring 14 inches in diameter.

D. —BANK HOLIDAY-RING.

The first hole of this ring was found on Whit-Monday, June 9th, 1930. With the exception of the round hole No. 5, all the holes of this ring were oval in shape and very large; nine out of the eleven oval holes were stepped, i.e, the outer half was deeper than the inner. There was clear evidence that these large oval holes had held two distinct uprights, in some cases the two cores being seen with a packing of hard chalk between them.

Where the cores in the outer part of the holes were well enough defined to see, the timbers seem to have been about 12 to 14 inches in diameter, and rather less on the inner side. The cores were usually better defined in the outer than in the inner part of the hole, probably due to greater depth. In hole 10, two cores were particularly well defined, 1ft. in diameter and 2ft. apart from centre to centre, with a packing of hard chalk between. In this hole there were two roundish shallow depressions about an inch deep in the floor, apparently marking where the timbers had stood.

What purpose the twin posts in these holes served can only be a matter of conjecture; it has been suggested that they might have supported a log walling, the horizontal posts being held together by the twin uprights; they could have served some function in connection with a roof (if the rings were roofed over, see page 309); or they may merely have resulted from a replacement of decayed timbers with new ones.

Another puzzling feature is that one hole (No. 5) should have been circular with a single post while all the others in the ring were oval with twin posts. A line drawn from the centre of the rings through this hole cuts the burial at stone hole 12, of the Stone-and-post-ring, but the line also cuts hole 2 of the 6-foot ring. If there was any significance in this it seems rather to link up the stone with the wooden structure and to suggest that they were contemporary, but it could be explained equally well on the supposition of this having been a point of special significance in the earlier timber structure, the nearest stone to it was therefore chosen as the site of burial. It will be seen that this single hole and the burial are on the eastern side of the rings.

The single hole 5 was dug at a slant and the core seemed to be inclined (see section 5, Plate III.); the outer cores in holes 8 and 9 also appeared to be inclined outwards, the latter at an angle of about one-sixth; the cores in holes 7 and 19 of the Stone-and-post ring were also inclined.

E.—THE 10-FOOT-RING.

The holes of the 10-foot-ring (roughly its radius from the centre) as may be seen on the plan are also rather oval in shape. These holes, however, had held only single posts, or if two as the oval shape suggests, the two posts must have stood close together so that they appeared as only one core. Traces of the core were found in all the holes of this ring. Holes 3 and 4 were stepped, i.e., the floors were of unequal depth like those of the Bank Holiday-ring, but no trace of a second core was found in either. The steps were 27 and 24 inches deep respectively. A shallow circular depression was noticed on the floor of hole 3, similar to those in hole 10 of the Bank Holiday-ring. The oval shape of the holes in this ring may be due to a desired slight re-adjustment in the position of the posts, or as suggested in connection with the oval holes of the Bank Holiday ring, the decay and restoration of some of the posts.

F.—THE 7-FOOT-RING.

The eight small holes of this ring seem to have been placed with regard to the position of the eight holes of the 10-foot-ring. This also places them symmetrically with the six holes of the inmost ring (6-foot-ring), for it will be seen that there are two holes between 1—2 and 3—4, and one between each of the other holes of the inmost ring. As was only to be expected from the small size of the holes in this ring no trace of the core was found in either of them, and they were filled with a distinctive brown mould without relics of any kind.

G.—THE 6-FOOT-RING.

The inmost ring with a radius of some 6 feet, consisted of six deep round holes; the cores formed by the timber uprights were noticed in holes 3, 4, 5, and 6; these timbers seem to have had a diameter of about 12 inches.

Howes H. 1—5.

Between the Fence-ring and the Stone-and-post-ring, on the south-western side, there is a solitary stone hole, and on either side of it two small post holes of the same character as those of the Fence-ring. Presuming that the stone and timber rings are not contemporary, it seems that these five holes are more likely to belong to the timber than to the stone structure. The fact that the post holes are identical in character with those of the Fence-ring seems to connect them with that ring and therefore with the timber structure as a whole.

It may be remembered that at Woodhenge on the south weno side, between two uprights of the B ring, a hole was found which there was reason to believe had held a stone. It is suggested that this solitary stone on the south-western side of the Sanctuary is analogous to the solitary stone at Woodhenge,1 whatever the meaning or significance of that stone may have been.

Note 1. 1 Woodhenge, p. 14.

THE CENTRAL POST HOLE

The central post must have been quite a slender one, the hole being only 42 inches deep, the diameter at top 20, and at bottom 10 inches. As the post cannot have been more than 10 inches across at the base. and must naturally have tapered if of any considerable height, it seems quite inadequate to have been the central roof-tree if the rings were roofed over as has been suggested. It may be remembered that a single upright stone once stood in the centre of the southern circle at Avebury. On the other hand it seems not altogether improbable that this small hole is a relic of the stake from which the rings were all laid out.

THE POSSIBILITY OF ROOFING

It has been suggested that the inner rings of posts may have supported a thatched roof. The idea suggested itself mainly on account of the strength implied by the size and depth of the post holes, the twin posts in the Bank-Holiday ring, and the fact of a central post (see above). There is no doubt that the posts of the four inner rings (excluding the 7-foot-ring) could have been used to support a roof, and drawings of several possible constructions have been made. One of the chief difficulties seems to be to give a reasonable explanation of the 10-foot-ring as well as the 6-foot ring; one reconstruction accounts for the twin posts in the Bank Holiday ring as serving the double purpose of supporting the ends of rafters and preventing their slipping, the ends of the uprights being assumed to be naturally forked trees; another plan utilises the twin posts as supports for a log walling.

It seems, however, that if a roof had been intended the ground plan would have been simpler, as any roof using all these uprights is necessarily a complicated structure. On the whole therefore it is felt that the arguments against there having been a roof are stronger than those in favour of one.

WERE THE STONE AND TIMBER RINGS CONTEMPORARY?

If the stone and timber rings were not standing at the same time it is at least certain that the stone must be the later; we know that timber did not supplant stone because the stone circles survived into the 18th century when they were seen and described by Stukeley. Had they been erected at the same time, however, all the timbers would naturally have disappeared leaving only the stones to mark the site. Nothing found in the excavation threw light on this question, the sherds of pottery found being similar in both stone and post holes, so there remains nothing but the plan to help us, It will be seen that if stones and posts were standing at the same time there was no way through the Stone-and-post ring; there would no doubt have been gaps between some of these uprights but nowhere more than some 3ft. wide; it is, however, not the want of width that strikes one so much as the awkwardness and lack of symmetry in an entrance having a post on one side and a stone on the other.

It will be seen further that some of the post and stone holes overlap each other, and this seems unlikely to have been the case if the stones and posts were put up at the same time. Cross sections were made through several of these overlapping holes in the hope of getting some information in this way, but the stone holes were too shallow to afford any reliable evidence. An entrance is definitely indicated in the Fence-ring and so it seems all the more unlikely that there should have been none in the next ring.

It is thought probable, therefore, that the stone and timber rings were not contemporary but that the stone circles succeeded to those of timber. If not contemporary, however, there can have been no long lapse of time between them, and the stone circles must have been planned while the details of the timber rings were still known, as proved by their common centre, and the fact that stone and post holes in the Stone-and-post ring are on the same circumference, and alternate with one another.

It has been suggested that Woodhenge was the forerunner of Stonehenge, and that the primitive timber structure was replaced by a more developed One in stone on a new site.1 At the Sanctuary there is evidence that also points to the replacement of timber by stone. At Stonehenge the diameter of the outer or Aubrey circle is just double that of the long diameter of the A, or outer ring at Woodhenge. It is interesting therefore to find that the diameter of the outer stone circle at the Sanctuary is just double that of the outer timber or Fence-ring.

Note 1. Woodhenge, p. 21.

PLAN OF TIMBER RINGS COMPLETE IN ITSELF.

As bearing on the question as to whether the stones and posts were contemporary it will be seen that the timbers form a plan complete in itself, and more intelligible without the stones than with them, a reasonable boundary being provided by the Fence-ring.

In the absence of the stones the centre is approachable from any point inside the Fence-ring but there is a noticeably clear way through the rings from N.E. to S.W.

This passes through the two pairs of post holes, on opposite sides of the Stone-and-post-ring, that are placed further apart than any other posts in this ring. The distance between these pairs, centre to centre, is 11ft. and 10¾ft.; the normal distance apart of the posts in this ring is 83 to 94ft.; in only one other instance (holes 1—3) is the distance as much as 10ft. The holes of the next two rings (Bank Holiday and 10-foot), though not further apart than the average, are conveniently placed. The passage continues through the 7-foot ring at the only points where these holes are so arranged that there is one on either side of the passage; finally the two opposite pairs of the 6-foot ring through which it passes are noticeably further apart than either of the other holes of this ring, e.e., 8ft., the greatest distance between any other two holes in this ring being 6½ft.

The holes of the timber rings were evidently laid out in pairs from the centre, so that a line drawn through one hole to the centre, if prolonged, will cut through a hole in the same ring on the opposite side of that ring— this can be tested by laying a rule on the plan; it is most striking in the posts of the Stone-and-post-ring. This method of laying ont would necessarily result in even numbers such as all the rings show, but the method does not apply to the Fence-ring or to the outer stone ring, and the stones of the inner stone ring were evidently placed to alternate with the posts of this ring.

Some of the holes of the inner rings look awkwardly placed on plan, but uprights in them could in most cases have been adjusted, if desired, to form circles as true as those of the outer rings.

If the theory of a roofed construction is discarded then the timbers must be pictured as free standing rings like those of Woodhenge [Map]. The two sites indeed appear comparable on general grounds, and in detail show interesting points in common. On each site there are six rings of holes with a single stone hole in the south-west side.

ORIENTATION.

There is no evidence of orientation at the Sanctuary any more than there is at Avebury itself; in this respect these two monuments differ from Woodhenge [Map] and Stonehenge which both show orientation. (On Lockyer’s claim for evidence of orientation at Avebury see W.A.M., xxxv., 515, June, 1908).

A DITCH SEARCHED FOR.

Aubrey speaks of a ditch and says—"I doe well remember there is a circular trench about this Monument or Temple, by the same token that Sir Robert Moray told me that one might be convinced and satisfied by it that the earth did growe."1 But Stukeley writes—‘he (i.e. Aubrey) erred in saying there was a circular ditch on Overton-hill."2 As Long points out3 there is no indication of a ditch or trench on Aubrey’s plan. Hoare also says that there was no appearance "of any ditch surrounding this circle of stones on Overton-hill."4 Incidentally this shows that the exact site where the circles had stood must still have been known in Hoare’s time. A glance at the plan of the area excavated will show that if there had in fact been a ditch surrounding the circles, within any reasonable distance, it would certainly have been found. The two long trenches on the east and north-east sides were made in searching for it, but as it was not found it may be considered as proved that in this particular Aubrey was mistaken and that Stukeley was right. Aubrey seems to have written his notes some considerable time after visiting the site, and it seems possible that he may have been confusing in his mind a ditch of one of the neighbouring barrows. His account of a ditch seems so circumstantial that it was not only hoped, but confidently expected, that a ditch would be found; indeed at one time it was actually thought that it had been found on the avenue side, but the would-be ditch proved after careful testing to be only a natural shallow channel in the chalk.

Note 1. Jackson’s Aubrey, 322; W.A.M, iv., 317.

Note 2. Abury, 32.

Note 3. W.A.M, iv., 328, note 2.

Note 4. An. Wilts, ii., 62, note.

DATE AND THEORY OF ORIGIN.

The evidence as far as it is at present known suggests that people living in the early Bronze Age (Beaker period) constructed on Overton Hill a series of concentric timber circles for ceremonial purposes. It is not necessary to picture these timbers as merely bare standing posts, they could have been coloured and adorned in a variety of ways.

These people some time later, but in the same "period," raised the circles of standing stones at Avebury. The site on Overton Hill was regarded as one of considerable importance, so when the circles at Ayebury were made it was thought desirable to connect the new site with the old by means of an "avenue" of standing stones, and the Kennet avenue was made and carried on to Overton Hill for this reason.

By this time the timbers may have been in a bad state of preservation, and as more in keeping with the stone avenue two circles of stones were erected in their stead, the same centre being retained, and the diameter of the outer stone circle being made just double that of the outer timber ring (Fence-ring). The new construction, consisting of only two stone circles, was simpler in design than the original timber rings for the reason that the ceremonial centre had now been transferred to the new site at Avebury.

The discovery of rings of timber uprights, that the evidence suggests were replaced by standing stones, on a site so closely connected with Avebury, is of no little interest in connection with the suggestion made with regard to Woodhenge [Map], that it was the forerunner of Stonehenge. (Woodhenge, 18). The fact that the timber was used in the midst of this sarsen-strewn country, where a practically unlimited number of naturally shaped and suitable stones were to be had in the immediate neighbourhood, is in itself remarkable, and shows that timber was not only used as a substitute when stone was not available, but in this case at least, was actually chosen in preference to stone.

Judging by the character of the pottery found the date of the original construction, and of reconstruction (if such took place) would fall within that part of the early Bronze Age known as the Beaker period, round about 1,500 B.C. (See also under Pottery).

THE BURIAL.

One burial was found. This consisted of a much crouched skeleton of a youth some 14 or 15 years of age, lying in a shallow grave on the inner side of the stone hole 12, in the Stone-and-post-ring, z.e., on the eastern side of the rings immediately behind the one single-post hole in the Bank Holiday ring (Plate X.).

The skeleton lay on its right side, head to the south, feet to the north i.e., facing east. The grave was 1½ft. deep, 3ft. long, by 2ft. wide. The grave and the stone hole cut into one another, and the body must have almost, if not quite, touched the inner face of the stone at the time of burial, if the stone was already standing. See Pl. III., 1.

The arms were crossed above the elbow in front of the face, the two hands seeming to enfold the face, finger bones being found over and under the facial bones; the head was bent forward over the chest, and the legs were crossed below the knees.

In front of the legs just below the knees lay the crushed fragments of a beaker. Intimately associated with the skeleton, apparently having been laid on the body when it was buried, were some bones of animals,1 some being slightly charred. A few small flecks of charred (or decayed?) wood were noticed among the bones of the skeleton.

The bones of the skeleton were nearly all broken, most of the limb bones being in several pieces. The skull and the beaker were crushed flat and a few fragments of both were missing; it seems that this was probably due to a certain amount of disturbance caused when the stone fell, or was thrown down and removed. Some of the crushing may be due to heavy modern agricultural machines.

Note 1. See Dr. Jackson’s report.

It is hardly possible that the burial was made before the stone hole was dug; the probability seems to be that it was made at the time the stone was erected, for the risk of bringing down the stone would have been considerable had the grave been dug later. As all the ground within and including the Fence-ring was dug over, had there been other burials they must have been found, so this with Woodhenge [Map] makes the second elaborate series of wooden circles that were not erected primarily as burial places. This solitary somewhat insignificant burial may have been of a dedicatory nature as the only one in the rings at Woodhenge [Map] is thought to have been. The evidence from the burial affords a striking parallel to that of the pottery as regards an overlap in cultures. While some of the pottery is of the West Kennet Long Barrow type the rest is equally characteristic of the succeeding "Beaker" period. The youth buried beside the stone was of Long Barrow people ancestry, but the vessel by his side is one typical of the "Beaker"? people, who invaded Britain at the end of the Long Barrow period, imposing their culture—and presumably conquering—the Long Barrow people who were previously predominant in southern Britain. Better evidence of overlap could scarcely be expected.

The only other human remains found were three pieces of a lower jaw scattered in stone hole 16 of the Stone-and-post-ring; the pieces were subsequently fitted together but do not make a complete jaw.

SARSEN STONES IN POST HOLES

A puzzling feature in the post holes was the presence, in practically all of fragments of sarsen stone, many of them showing scorching and fracture by fire. These pieces were found right to the bottom of the holes, in some, especially the smaller ones, perhaps only one or two small chips; they were unusually plentiful in the two "gate" post holes of the Fence-ring (Nos. 33—34), numbering in each about 60 pieces, large and small, the largest being about the size of a man’s double fists.

The presence of these sarsens in the post holes seems at first rather to. suggest that the posts succeeded the stones, or were at least contemporary with them. But it is at least certain that the stones survived the posts, and as there is no reason to think that the stones were shaped or other than naturally formed blocks of sarsen, it does not seem really to affect the question of priority.

A probable solution is that originally the site, and all the hill, was strewn with naturally deposited sarsens and that the site was cleared of them by breaking up by means of fire (see note 1, page 317) In this way the ground would be littered with their debris and some of it would find its way into the post holes with other rubbish lying on the surface, such as bones of animals, broken pots, flints, etc. Itis understood that numbers of similarly split sarsens are found in the excavations on Windmill Hill so that the method of breaking up sarsens with the aid of fire seems to extend to very early times.

It is not improbable that some of the larger pieces of sarsen were used as packing to keep the posts firm. ‘The fact that they were so unusually numerous in the "gate" post holes of the Fence-ring, seems to support the suggestion that the posts in these two holes supported some form of gate, and were therefore packed securely in order to support a strain.

An altogether exceptionally large piece of sarsen was found in post-hole 21 of the Stone-and-post ring; it measures 17in. X 12in. and 16in. deep, its base being 20in. below surface level (see Pl. III. 7). When this stone was lifted out of the hole it was found to be resting directly on the core which was particularly well defined in this hole. It is therefore certain that this large sarsen got into this hole after the post was decayed, and in some other way than that of the sarsens spoken of above. Much of its surface shows natural crust and it seems to have been broken off a larger boulder. It may be supposed that either at the time of the erection of the stones, or after their destruction had begun, this large fragment was dropped into the hollow marking the site of the hole, or purposely buried to be out of the way.

THE POTTERY.

The quantity of pottery found is small, but fortunately more than from the holes at Woodhenge [Map]. At Woodhenge [Map] most of the pottery and other objects came from the ditch or from under the bank, but at the Sanctuary there is no bank or ditch.

About 200 sherds in all were found, some showing distinctive ornament but many are plain and of indefinite character.

With the exception of three small pieces from the surface of Early Iron Age or Romano-British date, the pottery all belongs to one group, composed of two distinct but overlapping types, The earlier of these is known as the West Kennet, or Peterborough long-barrow type, the later as "Beaker" pottery.

Pottery of the West Kennet type seems to be characteristic of the long-barrow people who inhabited southern Britain before the arrival of the "Beaker" people who buried their dead in round barrows.

The Beaker people either themselves introduced the use of bronze into this country, or arrived about the time that it was first used. The Beaker period is therefore identical with that of the early Bronze Age in Britain, and the discovery of pottery of this type on any site shows that it must have been occupied in the Bronze Age.

The Beaker people presumably came as conquerers, but even so there is no reason to believe that they exterminated the older inhabitants, or that the earlier culture was entirely superseded.The association of the West Kennet and beaker types of pottery, not only in burials but also on living sites, is indeed good evidence to the contrary, and shows that elements of the older culture survived along with the new. The evidence of the burial found in the Sanctuary affords an example of this overlap. The youth buried, as his skeletal remains show, was a descendant of the narrow-headed long-barrow people, while at his side was placed a vessel of beaker type, that could not have found its way there but for the invasion of the "Beaker" people.

While there seems to have been among the West Kennet pottery a considerable variety of vessels, the most characteristic and best known form is that of a highly-ornamented round-bottom bowl with spreading lip and contracted below the rim. These are well represented by bowls in the British Museum, found in the Thames at Mortlake and Mongewell.1 The ware is coarse and imperfectly fired, even when the surface is burnt red, usually showing a black core; the paste is often mixed with broken shells or particles of flint or other stone, and and. The ornamentation shows great variety, some of it being produced by impressions on the soft clay of twisted cord or sinews, finger tips or finger nails, and very frequently of the articulating ends of bones of small birds and mammals2. Some of the fragments from the Sanctuary seem to have belonged to bowls of this type and are illustrated on Plates VII., VIII.

The fragments of beaker (except No. 2) are not illustrated, as the type is so well known, the ornament consisting exclusively of rows of horizontal parallel lines executed in the characteristic notched manner.

Note 1. Archæologia, lxii., 340.

Note 2. New light on an old Problem, Antiquity, September 1929, 283—291

Thanks are due to Mr. C. W. Pugh, M.B.E., Mr. E. L. Pegge, and to Lieut.-Col. R. H. Cunnington, R.E., for help rendered during the excavations. To Col. Cunnington we are indebted for the plan and measurements of the rings, etc., and to Mr. Pugh for the drawings reproduced in Plate VI. Mr. W. J. Osmond, of West Kennet, the former owner and occupier of the land, kindly gave us permission to excavate in the first instance, and subsequently allowed us to purchase this corner of his field in order that the site might be preserved.

We wish also to express our indebtedness to Sir Arthur Keith, M.D., F.R.S., for reporting on the human remains.

To Dr. J. Wilfrid Jackson, F.G.S8., Assistant Keeper of the Manchester Museum, for reporting on the animal remains.

To Dr. H. H. Thomas, of H.M. Geological Survey, for the identification of several specimens of minerals.

To Dr. T. W. Woodhead. Ph.D, M.Sc., F.L.S., for the identification of the charcoals.

To Mr. A. S. Kennard, A.L.S., for his report on the snail shells.

We have purchased the site and it is intended to mark the holes in the different circles in some suitable way so that visitors may be able to realise on the spot the size and general lay-out of the monument that once stood there.

It is hoped eventually to hand the site over to the care of some public body for the benefit of the public.

The pottery, etc., found on the. site will be placed in the Society’s Museum at Devizes. ‘The skeleton from the burial has been given to the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, Lincolns Inn Fields, London.

NOTE 1.—ON THE METHOD OF DESTRUCTION OF THE SARSENS.

During the excavation of the stone holes, especially those of the outer ring, the holes were found to have been enlarged, usually on the outer side; the floors of these holes were covered with a burnt layer and quantities of charred material consisting largely of charred straw; while in the soil filling the hole and round about it, numerous scorched pieces and fired flakes of sarsen were found, thus confirming the following method of destruction described by Stukeley:—‘‘ The method is, to dig a pit by the side of the stone, till it falls down, then to burn many loads of straw under it. They draw lines of water along it when heated, and then with smart strokes of a great sledge hammer, its prodigious bulk is divided into many lesser parts. But this atto de fe commonly costs thirty shillings in fire and labour, sometimes twice as much. ‘They own too ’tis excessive hard work, for these stones are often 18 foot long, 13 broad, and 6 thick [these figures refer to stones at Avebury itself], that their weight crushes the stones in pieces, which they lay under them to make them lie hollow for burning, and for this purpose they raise them with timbers 20 foot long and more, by the help of 20 men, but often the timbers were rent in pieces." Abury, 15—16. Holes nos. ], 2, and 41, of the outer circle, are probably those that held the stones shown by Stukeley as still standing in July, 1723 (Pl. V.). The enlargement of these holes in order to throw the stones, and the evidence of their destruction by fire was very marked.

NOTE 2.—MILL FIELD AND THE WINDMILL.

The field was formerly known as Mill Field (Smt, p. 169, H. vi., q.; W.A.M.,, vi., 327. Hoare Ancient Wilts, II., 62, note), and for this reason the possibility of the post holes being the foundations of a windmill had to be considered. The earliest form of windmill in this country was a post-mill, in which the whole structure hung and revolved on a central post, and was pushed round to face the wind by means of a long tailpost which stuck out behind, the stout central post being strengthened by means of four stout timber struts. It was not until the middle of the 16th century that the tower mill was introduced in which the body of the mill was fixed and the cap only turned by hand to the wind. (It was not until 1750 that the fan wheel was invented by which the mill is self-adjusting). This later form of mill rests on a tower, sometimes of wood with brick or stone foundations, or of these materials throughout.

Even if the post holes at the Sanctuary were suitable for a post-mill, which they are not, it would have been impossible to adjust it by means of a tail-post with any of the stones of the inner circle standing as we know they were at least as late as Aubrey’s time; of the later tower type of mill there is no trace; not a single sherd of pottery or other object of medieval date was found.

Indeed the actual site of the mill seems to have been found by Thurnam in the much ploughed mound south of the Sanctuary. (Goddard’s List, Avebury 23; Smith, p. 169, H. vi., 1). His excavation in 1854 "disclosed deep trenches in the chalk and bits of old-fashioned pottery, several large nails, and a ring or loop of iron. If not the remains of the barrow described by Stukeley, it may have been the site of a windmill removed before the time of Aubrey, whence the name of the field." The foundations of post-mills seem often to have been in the form of deep trenches dug in the form of across, and the sites abound with pottery, nails, etc., of the period. (See Williams-Freeinan, Meld Archeology, p. 115; on the development of windmills, Bennett and Elton’s History of Corn Milling, vol. ii.; Report of Soc. Pro. An. Buildings, 1930, p. 36).

NOTE 3.—THE IDENTIFICATION’ OF BARROWS MENTIONED BY AUBREY AND STUKELEY.

It was attempted to locate the site by means of the barrows depicted by Aubrey and Stukeley, but this proved useless because it was not possible to decide whether their descriptions referred to mounds still visible or not. Aubrey’s two plans both show two round barrows close to the eastern side of the outer ring. One of Stukeley’s sketches (Tab. xxix.) also shows two barrows more or less in the same position, and in his description he particularly associates two barrows with the Sanctuary, as Aubrey does in his plan. "One near the temple on Overton-hill was quite level’d for ploughing Anno 1720; a man’s bones were found within a bed of great stones, forming a kind of arch." Beads of amber were found, and " several enamel’d British beads of glass. I got some of them white in colour, some were green.... I bought a couple of British Beads, one large of a light blue and rib’d, the other less, of a dark blue, taken up in one of the two barrows on Hakpen-hill, east of Kennet avenue. These two barrows are ditch’d about and near one another " (page 44). Again on page 33 "Here is a great number of barrows in sight from this place, two close by".

It seemed that one or both these barrows might be identified with one or both of the two mounds that can still be seen south of the road; one is on down land in good condition, the other west of the Ridgeway in Mill Field, on arable land and much scattered by the plough.

In the photographs taken from the air this latter mound is seen to have a well defined ditch round it; this is the mound opened by Thurnam in 1854, and thought by him to be perhaps the one that Stukeley says was "quite levelled for ploughing, anno 1720." But in a sketch dated 1724 (Tab. xix.) this barrow is still shown as a large mound by Stukeley, and even now more than 200 years later it is not nearly "level’d"; moreover Thurnam’s excavation seems to have shown the mound to be the site of a Windmill? (though perhaps originally a barrow), and its contents were incompatible with the "arch of stones," [Note. Stukeley states "forming a kind of arch"] etc., as described by Stukeley.

Now that the site of the Sanctuary is known it seems certain that the two barrows particularly referred to by Aubrey and Stukeley as close to the eastern side of the Sanctuary no longer exist.

Stukeley shows three barrows ina row along the south side of the road (Tab. xix.), that have all been dug away. North of the road the diggings have encroached on, and left exposed, a fine section of the ditch of one of the barrows there.

Note 1. W.A.M., vi, 328. Thurnam in speaking of prehistoric pottery usually describes it as "Ancient British" or "coarse native." The term "old fashioned" implies something different and in all. probability medieval pottery.

Note 2. See Note 2 above.

NOTE 4.—THE GEOLOGICAL CONDITIONS.

The rubbly condition found to a depth of one to two feet seems to be characteristic of the Holaster planus zone in this region, at the bottom of the Upper Chalk and just above the Chalk Rock. The green-coated and iron-stained chalk nodules that appear to be characteristic of the Chalk Rock were very noticeable at the bottom of the deeper holes. The site is about 560 feet O.D.; the nearest Bench Mark being 562. 4. (We are indebted to Mr. H. C. Brentnall for information derived from the Geological Memoir). A considerable area east of the Ridgeway (north and south of the road), has been dug over for the sake of the chalk rubble found here and formerly much used for road making, yard paving, etc.

NOTE 5.—THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN SARSEN-STONE AND WOODEN POST HOLES.

Holes that have held stone uprights are generally angular, or sub-angular, and shallow in proportion to their width and breadth, while wooden post holes are circular or oval and deep in proportion to their other dimensions. Not only the different character and shape of the holes themselves, but experience gained at Woodhenge [Map] enabled us to at once appreciate the nature of the filling-in of the post holes. The method of distinguishing the core, or position formerly occupied by the wooden posts, is fully described in Woodhenge [Map] (page 22), but it may be as well here briefly to summarise the method.

In digging out the holes with care by means of a small garden fork, it may be seen that the central part of the filling differs in colour and hardness from that of the rest of the filling. If this central softer and darker material is carefully removed, leaving the rest of the filling undisturbed, a pipe-like circular cavity is left. This sharply demarcated difference in material could not have resulted from an intentional filling up of the hole, or by a process of slow natural silting, and it is evident that the central part represents as in a mould the post that originally stood in the hole. As the post decayed the space occupied by it was gradually refilled by fine rubble mixed with organic matter —decayed vegetation—silting in from the top, and this remains distinct from the packing of hard chalk originally rammed round the butts. Occasionally, especially near the bottom and in the deeper holes, actual fragments of decayed wood may be found, or sometimes only a grey powdery substance. Often it is only quite in the lower part of a hole that any sign of a core can be detected at all, and in others they altogether elude detection.

In a hole that once held a stone the conditions are naturally entirely different, for the stone must have been removed with a certain amount of violence and resulting disturbance in the hole, and cannot have decayed or faded away in situ, as a wooden post does, without any disturbance or outside interference.

PLATE I.

General plan of the Sanctuary showing the circles of stone and post holes, the avenue, etc.

The area excavated is shaded green.

Only every fifth hole of the outer stone ring is numbered.

The stone holes of the inner stone ring (Stone-and-post ring) are even numbers and the posts of this ring are the odd numbers (see Plate II.).

Red—Stone holes.

Black—Post holes of Fence-ring, Stone-and-post ring, 7-foot ring, centre hole and holes on either side of the single stone on the south-western quarter.

Black outline—10-foot ring.

Green outline—Bank Holiday ring and 6-foot ring.

PLATE II.

Plan of post holes with single stone hole in south-western quarter.

The holes are shown on this plan as measured at the bottom.

Solid black—Fence-ring and 7-foot’ring (inner); post holes in line with south-western stone hole.

Black outline—Stone-and-post ring (posts only).

Green outline—Bank Holiday ring and 6-foot ring (inner).

Red outline—10-foot ring, stone hole in south-western quarter.

PLATE III.

1.—Section and plan of stone hole 12 (a) with the grave (b).

2, 3.—Sections of holes 1 and 6 of the Bank Holiday ring showing un- equal depth or step between inner and outer part of the holes, In hole 1 the step was 20 inches deep and there was a slight depression in the floor of the deeper half,

4.—Section of hole 10 of the Bank Holiday ring showing slight step at the bottom and two cores representing the timber uprights as seen in the lower part of the hole with a packing of hard chalk between, the cores were about 1ft. in diameter and 2ft. apart centre to centre.

5.—Section of hole 5 in the Bank Holiday ring. Except No. 5 all the holes in this ring were oval and showed two cores marking the position of the former uprights. No. 5 was circular with a single well defined core. Both core and hole sloped outwards as shown.

6.—Section of hole 6 of the 6-foot ring. These narrow holes were awkward to clear out and must have been difficult to dig in the first place The enlargement near the bottom in many of these narrow holes was made probably to provide space for the digger’s knees to enable him to reach the bottom of the hole which otherwise was almost an impossibility.

7.—Longitudinal section through holes 17 to 30 of the Stone-and-post ring showing the alternate stone and post holes, the stone holes being the even and the post holes the odd numbers. In post hole 21 the position of a large piece of sarsen found near the top is indicated with a well defined core below it.

PLATE IV.

1.—Plan of the Sanctuary after Aubrey (reduced). It shows two barrows close to its eastern side, also the bend in the avenue at its junction with the rings, which Aubrey gave it apparently in order to include the three stones numbered N1 and N2 on plan (Plate I.), and one stone beyond, the hole for which could not be definitely verified by excavation (see page 306).

2.—Plan of the Sanctuary after Stukeley (reduced). It shows the two stone rings as ovals, with the first pair of avenue stones as some 80ft. from the outer ring.

PLATE V.

Stukeley’s sketch of the Sanctuary entitled ‘Prospect of the Temple on Overton Hill, 8 July, 1723. The Hakpen, or head of the Snake in ruins," Stukeley says "It had suffer’d a good deal when I took that prospect of it, with great fidelity, anno 1723, which I give the reader in plate xxi. Then, about sixteen years ago, farmer Green aforemention’d took most of the stones away to his buildings at Bekampton; and in the year 1724 farmer Griffin plough’d half of it up. But the vacancy of every stone was most obvious, the hollows still left fresh, and that part of the two circles which I have drawn in the plate was exactly as I have represented it. In the winter of that year the rest were all carry’d off, and the ground ploughed over." (Abury, 31).

The inner ring is represented by holes only, all the stones evidently hav- ing been removed. ‘The stone lying outside the rings, to the right, must be the one that stood in the hole N1 or N2 on plan (Plate I. and page 306).

PLATE VI.—FLINTS.

A considerable number of small flakes and chips of flint were found in the surface rubble round about the holes 15, 16, and 19 of the Stone-and- post ring. These seemed to be debris of flint knapping. Some half-dozen or so scrapers were found on the surface, and one small barbed and tanged arrowhead, weathered white.

1.—Arrowhead of grey flint, with rudimentary tang and poor workmanship. Found 4½ft. deep in hole 5 of the Bank Holiday ring.

2.—Arrowhead? of grey flint, irregular in shape and of poor workmanship. Found 2½ft. deep in the packing of hole 6 of the Bank Holiday ring.

3.—Arrowhead of flint with hollow base, weathered white, worked on both sides of one edge only. Found in hole 1 of the outer stone circle.

4.—Small spear or lance-head of flint, weathered white on one side, grey on the other. Found in surface rubble.

PLATE VII.—POTTERY.

1.—Rim fragment of rather fine red ware ornamented on the inside with incised lines forming triangles. The ornament and ware recalls that of beakers but no parallel has been found to this ims¢de decoration and it suggests that the fragment is that of an open shallow bowl or platter. Found 2½ft. deep in hole 3 of the 6 ft. ring.

2.—Rim fragments of a beaker with horizontal rows of characteristic notched lines. ‘This fragment is interesting as showing a raised beading ¾ of an inch below the rim, a feature that occurs on handled beakers and those with inbent rims, as a class a late type.1 Found in hole 29 of theouter stone circle.

3—10.—Sherds typical of West Kennet Long Barrow pottery, paste black to brown, coarse and mixed freely with pounded flint and shell. 3 and 6 were found at the bottom of hole 8 of the Bank Holiday ring; 4, 4 feet deep in hole 2 of the 10-foot ring; 5 and 7, 2½ft. deep in hole 3 of the 6-foot ring; 8, at the bottom of hole 3 of the Bank Holiday ring; 9, 4ft. deep in post hole 23 of the Stone-and-post ring; 10, 3ft. deep in hole 9 of the Bank Holiday ring.

No, 3 may be compared with Nos, 28 and 31 from West Kennet Long Barrow2; No. 4 with 53; No. 7 with 58; No. 9 with 23; No. 10 with 69.

Note 1. Dr. Fox has dealt fully with these in Archæologia Cambrensis, June 1925,

Note 2. Pottery from the Long Barrow at West Kennet. M. E. Cunnington, 1927.

PLATE VIII.—POTTERY.

11.—Rim fragment of bowl?, slight ridge below rim on inside, fairly well baked buff ware. Found 2½ft. deep in post hole 13 of the Stone-and-post ring.

12.—Rim fragment of bowl? with ridge below rim on the inside similiar to No. 11 above. Paste black mixed with flint. Found at the bottom of hole 10 of the Bank Holiday ring.

13.—Rim fragment of bowl? very poor soft brown ware, exterior tooled. Found near the bottom of hole 3 of the Bank Holiday ring.

14, 15, 17, 18.—Four sherds of fairly hard well baked pottery, surface a dull red, paste black, ‘These look as if they were all sherds of the same pot but were found in three different holes. No. 14, 1ft. deep in hole 15 of the Bank Holiday ring; No. 15, 3ft. deep in hole 13 of the same ring; Nos. 17 and 18, 2ft. deep in hole 4 of the 10ft. ring.

16.—Rim fragment of brown ware with flint particles, ornamented as shown on the flat of the rim with diagonal lines of small punch marks. Found in hole 26 of the outer stone circle.

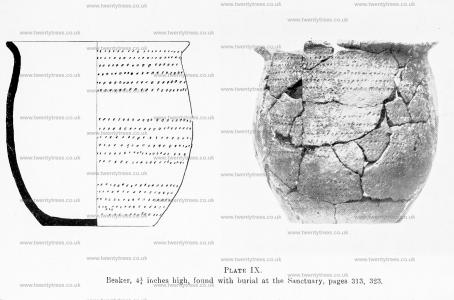

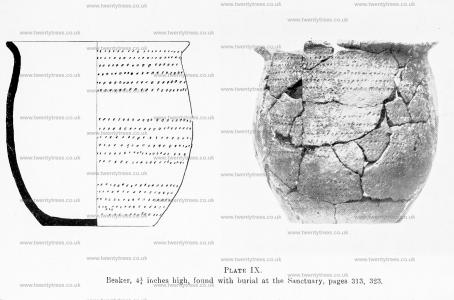

PLATE IX.

Photograph and drawing of the beaker found in front, and just below the knees, of the skeleton in the burial close to the inner side of the stone hole 12, in the inner stone circle. Height 4½in., rim diam, 4in., base 2½in. Paste black and sparingly mixed with particles of flint, surface dull brown, rim; out-bent. Ornamented with horizontal rows of small punch marks arranged in three groups with plain zones between, six rows in the two upper groups and five in the lower.

The vessel approximates to type B, i.e. ovoid cup with recurved rim. Of the beakers illustrated by Abercromby No. 42 bis, from Stoford, Somerset, is nearest to it with regard to the punch mark decoration.1

It may be remembered that a skeleton burial with a beaker was found close to the foot of the stone "Adam [Map]," at Beckhampton, when it fell in 1911.2

Note 1. Bronze Age Pottery, vol. 1.

Note 2. W.A.M., vol. xxxviii., 1.

PLATE X.

The crouched skeleton found close to the inner side of stone hole 12 of the Stone-and-post ring. The stone hole is seen lengthwise to the left, i.e. in front of the skeleton, the left knee is on the edge of the hole. The upper part of post hole 13 may be seen beyond the stone hole.

The article continues with a series of tables.

REPORT ON HUMMAN REMAINS FROM THE SANCTUARY, By Sir Arthur Keith, M.D., F.R.S.

All parts of a human skeleton are present, the bones being those of a lad about 14 years of age and about five feet in height. My estimate of the age is founded on:—(1) the epiphyses have not yet joined the ends of the long bones; (2) the parts of the pelvis are unjoined; the skull bones are thin (5mm. in vault) and sutures are quite open; (3) the third molar (wisdom) teeth are still unerupted; all the others are in place, but only the first molar shows signs of wear. The teeth are free from disease. ‘The stature is estimated from the length of the femur and tibia. Tne femur measured without epiphyses (maximum length) is 355mm.; with epiphyses 415 mm.; the tibia without epiphyses 317mm.; with epiphyses 355mm. The tibia is 86% of length of femur—relatively a long tibia. The infra-trochanteric part of the femur shows a moderate degree of flattening—the side to side diameter being 29mm. and front to back thickness 25mm. The upper part of the shaft of the tibia at nutrient foramen has antero-posterior diameter of 29mm. with transverse of 21.5 mm.

As concerns the skull—the lad shows features which lead us to regard him as being of the same type as the people who buried their dead in long barrows. The skull is slightly deformed by earth pressure; its maximum length now measures 195mm.; its maximum width 136mm.—the width being just under 70% of the length. ‘The narrowness and length are no doubt due to some slight extent to posthumous distortion but when allow- ances are made on this score the skull is still long and narrow. ‘The fore- head is wide, 103mm. (min. width); maximum frontal width 119mm. The median frontal suture (metopic) is still open and this may account for the width of forehead. ‘The skull is not high; at its highest point with the skull oriented in the Frankfort plane the vault rises 107mm. above that plane. he skull viewed from above shows a long oval form. All the features of skull and skeleton lead me to regard the lad as a member of the long barrow people.

As to characters of the face little can be said for although the jaws are preserved they cannot be articulated to the skull because the basal parts of the skull are missing.

REPORT ON THE ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE SANCTUARY. By J. Wilfred Jackson, D.Sc, F.G.S.

The collection of animal bones found at the above site are somewhat imperfect and not very numerous. They are, however, of some interest in connection with those found at "Woodhenge [Map]" and reported upon recently. In the main they represent animals used as food.

The domestic animals represented are horse, ox, pig, and dog, while others are cat, field vole, and toad.

Horse.—An unbroken cannon bone or metacarpal from E 2 belongs to this animal. It measures 210mm. in length and has a mid-shaft diameter of 30mm., and indicates a small, slender-limbed animal, about 124 hands in height, of the "plateau" or Equus agilis type, as at All Cannings Cross and similar stations.

Ox.—The bones of oxen are fairly numerous but much broken in the usual way for marrow. Two carpal-bones from D 3 and C 29 are of the small type and suggest the Celtic ox (Bos longifrons), but all the others are larger and more robust and agree closely with the remains of the large ox found abundantly at Woodhenge [Map]. Unfortunately, no horn cores are present, but the various bones appear to indicate a bigger ox than the typical Bos longtfrons of Early Iron Age sites.

Pig.—Various split bones and three teeth belong to this animal. They all agree with similar remains from Woodhenge [Map]. A tibia from D 12 in a perfect condition measures 209mm. in length and is somewhat longer than the one from Woodhenge [Map] measuring 180mm.

Dog.—-There is an imperfect humerus of this animal from C 23. It is much weathered and root-marked, and represents a small animal.

Cat.—This animal is represented by a fragmentary scapula from C 27.

Field Vole..—A skull fragment and lower jaws from C 28 belong to this animal.

Toad.—The remains of at least eight individuals are represented by numerous bones.

The following were found immediately on the top of a human skeleton burial, C 12:—

Ox.—A lower tooth, toe-bone, split tibia, etc., belonging to a small animal.

Pig.—Teeth and a few bones.

Fragment of antler of red deer.

It is interesting to note the absence of sheep from the above collection of remains.

The absence of sheep bones as noted by Dr. Jackson is particularly interesting in view of the extreme scarcity of the remains of this animal at Woodhenge [Map] also. Whether it is due tothe rarity of this animal in Britain in the early and middle Bronze Age, or a prejudice against it on ceremonial sites such as these, must for the present remain uncertain.

In addition to the bones sent to Dr. Jackson a few fragments of antlers of red deer were found, one at the bottom of hole 2 of the 6-ft. ring, one in hole 4, and another at the bottom of hole 2 of the 10-foot ring.

Toad bones.—In some of the post holes quite a number of these bones were found in a very fragmentary state, only a selection of these being sent to Dr. Jackson. Their presence in the holes may be due to the animals creeping into the decaying trunks for shelter. In the grave beneath a neighbouring barrow a number of what were reported as frogs’ bones were found some years ago.1 Mr. Mortimer records that in a Bronze Age barrow in Yorkshire he found a number of bones of toads and frogs in the lower part of the mound near the interments.2

Note 1. W.A.M., xx., 343.

Note 2. Forty Years Researches, 351—2.

NIEDERMENDIG LAVA.

Some twenty fragments of this stone were found scattered throughout the lower half of post hole 27 of the Stone-and-post ring. They are small, mostly rounded pieces, and show no sign of use.

Dr. H. H. Thomas, H.M. Geological Survey, who identified the rock, describes it as "particularly interesting and its occurrence difficult to ex- plain. It is lava (nephrite) from Niedermendig on the eastern slope of the Kifel. Its source is without question. This rock was imported by the Romans into England in considerable quantity for millstones, for which its hardness, cavernous nature, and rough surface make it eminently suitable. I know, however, of no occurrence of this rock in Britain which could be attributed to pre-Roman occupation."

The presence of this rock from the Rhine area, in the bottom of a deep post hole at the Sanctuary, is a remarkable discovery. There is no reason to assume that this particular hole was disturbed in Roman or medieval times, when this rock is known to have been in use in the country, indeed traces of a core representing the decayed timber were found and this proves that the hole had not been disturbed.

It is tempting to connect the discovery with the Beaker people who are generally thought to have reached this country by way of the Rhine valley. It might have been brought over by them as a mealing stone, and subsequently being broken, the fragments could have found their way into the filling-in of the post hole, along with other debris from the surface. The use of this rock was known to the Beaker people in the Rhine area, where it was also used by their predecessors, late Neolithic people of the "Michel-berger" culture.1

Haematite. One piece was found at the bottom of post hole 11 of the Bank Holiday ring, and another about 3ft. deep in hole 7 of the 10-foot ring. It is hoped to publish a report on the charcoals later on in this volume.

Note 1. Mannus vi., 1914, 283—294, fig. 10: P. Horter, Dee Basaltlava Industrie bei Mayen (Rheinland) in vorromischer und romischer Zerit. I am indebted for this reference to Herr Georg Kraft, of the Museum fur Urgeschichte, Freiburg.

REPORT ON THE NON-MARINE MOLLUSCA. By A.S. KENNARD, A.L.S., AND THE LATE B. B. WOODWARD, F.L.S.

Thirty-five samples of earth from as many post-holes were submitted to us for examination and from these we obtained thirty-two species of non-marine mollusca. The samples varied somewhat in character, some containing far more humus than the remainder. Chips of sarsen, small flint flakes, and burnt flints were also present. The preservation of the shells also varied, but these differences would have arisen from the differences in the matrix. A large number of bones of small vertebrates were also present, a feature that did not occur at either Stonehenge or Woodhenge [Map]. We have tabulated the number of samples in which each species occurred, thus in- dicating the relative frequency.

List of species - see Original