Bronze Age Gold

Bronze Age Gold is in Bronze Age Artefacts.

Manton Barrow aka Preshute G1a [Map] is a Bronze Age Round Barrow excavated by Howard B. Cunnington and Maud Cunnington née Pegge who discovered a number of significant artefacts including gold artfacts. See Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1907 V35 Pages 1-20.

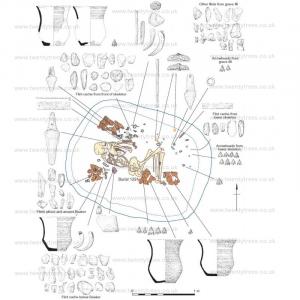

Golden Barrow aka Upton Lovell 2e [Map]. Bronze Age Barrow containing a rich collection of artefacts including:

[All information and photos sourced from Wiltshire Museum]

Amber spacer-plate necklace. This necklace was once made of around 1,000 amber beads, but now just over 300 survive. The flat 'spacer-plates' were drilled to hold the six strings of beads in place. Detailed examination suggests that the beads may have been from two necklaces. The necklace may have been made in Denmark or on the Baltic Coast. Necklaces with similar 'spacer-plates' have been found that are made of jet, which comes from Whitby. This suggests that this style of necklace was also made in Britain, using local materials.

Amber spacer-plate necklace. This necklace was once made of around 1,000 amber beads, but now just over 300 survive. The flat 'spacer-plates' were drilled to hold the six strings of beads in place. Detailed examination suggests that the beads may have been from two necklaces. The necklace may have been made in Denmark or on the Baltic Coast. Necklaces with similar 'spacer-plates' have been found that are made of jet, which comes from Whitby. This suggests that this style of necklace was also made in Britain, using local materials.

Gold plaqueMade from gold sheet less than 0.1mm thick, originally it was fixed to a backing, probably of wood. The plaque would have been sewn to an item of clothing, perhaps a cloak.

Gold plaqueMade from gold sheet less than 0.1mm thick, originally it was fixed to a backing, probably of wood. The plaque would have been sewn to an item of clothing, perhaps a cloak.

Gold drum-shaped beads. These eleven beads may have been part of a necklace or were possibly sewn onto clothing as decoration. They were made from coiled strips of gold with a gold cap at each end.

Gold drum-shaped beads. These eleven beads may have been part of a necklace or were possibly sewn onto clothing as decoration. They were made from coiled strips of gold with a gold cap at each end.

Gold caps. May have once decorated the ends of wooden staffs or sceptres.

Gold caps. May have once decorated the ends of wooden staffs or sceptres.

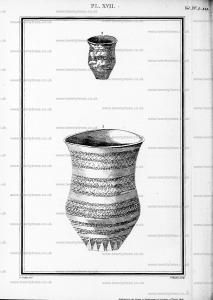

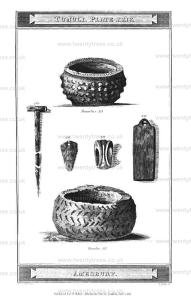

Incense 'grape cup'. These miniature pottery vessels were specially made to be used in funeral ceremonies and were placed in cremation burials, usually of women. These may have been fired on the funeral pyre and used to burn scented plants, hallucinogens or oils during a funeral ceremony. Holes in the side allowed the fragrant smoke to escape into the air.

Incense 'grape cup'. These miniature pottery vessels were specially made to be used in funeral ceremonies and were placed in cremation burials, usually of women. These may have been fired on the funeral pyre and used to burn scented plants, hallucinogens or oils during a funeral ceremony. Holes in the side allowed the fragrant smoke to escape into the air.

Shale pendant and gold cover. Cone-shaped shale pendant, decorated with incised lines. The cone was encased in gold sheet, decorated with the same incised lines.

Shale pendant and gold cover. Cone-shaped shale pendant, decorated with incised lines. The cone was encased in gold sheet, decorated with the same incised lines.

The Amesbury Archer [Map] is the remains of a man aged around forty at the time of his death from the Alps who was buried in Amesbury around 2300BC and discovered in May 2002 during the development of new housing. He is named 'The Archer' as a consequence of the large number of arrowheads found with him. His grave contained the largest number of artefacts of any grave of a similar period including the earliest known gold objects in England, five beaker funerary pots, three tiny copper knives, sixteen barbed flint arrowheads, a kit of flint-knapping, metalworking tools including cushion stones and some boar tusks. On his forearm was a black stone wrist guard. A similar red wrist guard was by his knees with a shale belt ring and a pair of earrings, the oldest gold objects found in England. An eroded hole in his jaw showed that he had suffered from an abscess, and his missing left kneecap suggests that he had an injury that left him with a painful lingering bone infection. His remains are on display in the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum [Map].

The Amesbury Archer's Companion is the remains of a man raised locally aged between twenty-five and thirty at the time of his death buried around 2300BC near to the Amesbury Archer. He appears to be related to the Amesbury Archer as they shared a rare hereditary anomaly, calcaneonavicular coalition, fusing of the calcaneus and of the navicular tarsal (foot bones). Inside his jaw were found a pair of gold earrings or hair ornaments in the same style as the Amesbury Archer's.

Photos sourced from Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum [Map] and Wessex Archaeology.

Archaeologia Volume 15 Section XI Page 128. William Cunnington, Archaeologia, Vol. 15, p.122-26

August 1st, Heytesbury 1803.

The tumulus [Golden Barrow aka Upton Lovell 2e [Map]] opened last Thursday in Upton Lovel parish, is situated a few yards north of the river Wily. It is of a pyramidical form, the base length 58 feet by 38 feet wide [g] and 22 feet in the slope, and stands from east to west. The northside of the barrow is extremely neat, the fouth side is much mutilated. On making a section lengthways on the barrow, at about two feet deep we found in a very shallow cist, human burnt bones piled in a little heap; and at the distance of a foot a considerable quantity of ashes [h] which contained small fragments of human bones; above, and at two feet distant from the bones were found the following articles of pure gold, which are neatly wrought, and highly burnished, viz. about thirteen gold beads made in the form of a drum, having two ends to screw off and perforated in the sides; [i] 2ndly, a thin plate of the same metal 2.25 inches by 5.25 inches; this is very neatly ornamented, as you will see by the annexed drawing: [k] 3dly, a beautiful Bulla (as I conjecture) of a conical form; [l] the inside of this is a solid cone of wood, the gold -which completely covered it is very thin; at the base are two holes for a thread or wire by which it was suspended; near the above were found four articles, viz. two of each, that appeared once to have covered the ends of slaves. [m] Among the gold ornaments lay several flat pieces of amber, the eighth of an inch in thickness, and about an inch wide; there were all perforated lengthways, but were sadly broken in getting out. What is very extraordinary, there were also nearly one thousand amber beads of different sizes. Close to the pile of ashes we found a very small urn, a lance-head of brass, and a pin of the same metal. The urn is of a very extraordinary form, appearing exactly as though it had been stuck all over with small black grapes. In this barrow, contrary to the usual method of interment on the Downs, which are on or in the native soil, we found the cist nearly on the top; and this deviation was probably occasioned from the wetness of the foil, being near the river, or it might have been the manner of interring their great chieftains. From the vail quantity of beads, it might be conjectured that a female had been interred here, but it is well known that our British chiefs wore pearls, beads, etc. On some of the coins of Conobeline we fee beads or pearls on the head. We find in other respects similar method of interment to what we find in many other barrows; the small urn, lance-head of brass, brass pin, etc. are common. From the profusion of valuable ornaments, for valuable they must have been at the period of their interment, we might rationally conclude this barrow to have been the sepulchre of some great chief; in all probability a chief of the Belgic Britons.

I am. Sir,

Your most humble Servant,

William Cunnington.

A. B. Lambert , Esq. Boyton House .

Note g. The length on the top 21 fe

Note h. A circumstance very common.

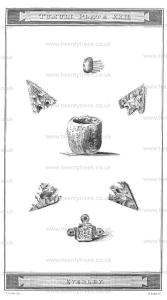

Note i. See fig. 5.

Note k. You see only a part of this plate: the whole length was about six inches; the pieces broken off had holes in the corners, perhaps used as a bread plate.

Note l. See fig. 1 ; the bafe of this is neatly ornamented

Note m. See fig. 2, 3.

Archaeologia Volume 15 Section XI Page 128. TUMULUS XX (AW 98) Copy of a letter to H.P. Wyndham Esq July 28th 1803.

William Cunnington, Manuscript Letters, Vol., p.35-6

Sir I have this day opened a barrow in Upton Lovell [Golden Barrow aka Upton Lovell 2e [Map]] it is situated in the meads a few yards north of the river Wylye. As the discoveries in this barrow are more important in their nature than any other ever yet made I hasten to inform you the particulars. This Barrow of a pyramidal form or rather like the common of houses, pointing East to West, is in the base 52 by 32 feet, the slope 22ft, the length on the top 22 feet. The North side of the barrow is extremely ? the south side is much mutilated. On making a section lengthways of the barrow, at about two feet deep we found in a very shallow cist human burnt bones piled in a little heap, and at a foots distance a considerable quantity of ashes, which also contained small fragments of human bones, upon which and at two feet distant from the bones were found the following articles of pure gold, which are neatly wrought and highly polished, viz about ten gold beads made in the form of a drum ? two ends to off and perforated in the sides..see Plate XI fig 5 ~.a thin plate of the same metal nearly 9 inches by 6 inches long , this is very neatly ornamented as you will see by Plate XI fig ?. by a beautiful Bulla of a conical form, see fig 3 in the same plate- and inside this is a solid cone of wood, the gold which completely covered it is very thin, at the base are two holes for a thread or wire by which it was suspended see fig 4. near the above were found of gold four articles viz.. two of which that appeared once I have covered the ends of staffs some of my friends say they are small boxes. see plate XI fig 1 and 2. Among the gold ornaments lay several flat pieces of amber, about the eight of an inch in thickness , and about an inch wide, -they were all perforated lengthways but were sadly broken in getting out. (see plate two fig 2 when joined they were the exact form of those found in Deverell Barrow only bigger). What is every extraordinary there were also nearly one thousand amber beads of different sizes see Plate X fig 2.- Close to the pile of ashes we found a very small urn see Plate X fig 1. Also a lance head of brass and a pin of the same metal-see the same plate. The urn is of a very extraordinary form, appearing as though it had been studded all over with small black grapes. In this barrow, contrary to the usual custom of interment on the Downs, which is generally on, or in the native soil we found the cist nearly on the top of the barrow and this deviation was probably occasioned by the wetness of the soil, the barrow being near the river. We find in other respects a similar method of interment to what we find in many other barrows, the small urn, lance head of brass, brass pin etc are common. From the profusion of valuable ornaments, for valuable they must have been at the period of their interment, we might naturally conclude this barrow to have been the sepulchre of a great chief of the Belgic+ Britons. + Mr Coxe objects to the word Belgic, suppose we say a British chief near the time of Caesars invasion.

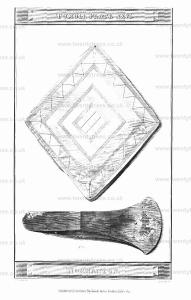

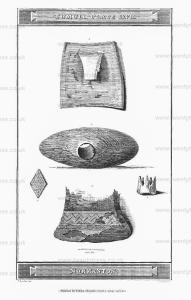

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 158 [Map]. Though Dr. Stukeley has given an engraving of this tumulus, under the title of BUSH BARROW, it does not appear that he ever attempted open it. It was formerly fenced round and planted with trees, and its exterior at present bears a very rough appearance from being covered with furze and heath. The first attempts made by Mr. Cunnington on this barrow proved unsuccessful, as also those of some farmers, who tried their skill in digging into it. Our researches were renewed ill September, 1808, and we were amply repaid for our perseverance and former disappointment. On reaching the floor of the barrow, we discovered the skeleton of a stout and tall man lying from south to north: the extreme length of his thigh bone was 20 inches. About 18 inches south of the head, we found several brass rivets intermixed with wood, and some thin bits of brass nearly decomposed. These articles covered a space of 12 inches or more; it is probable, therefore, that they were the mouldered remains of a shield. Near the shoulders lay the fine celt1 Tumuli Plate XXVI. No. 1, the lower end of which owes its great preservation to having been originally inserted in within a handle of wood. Near the right arm was a large dagger of brass, and a spear-head of the same metal, full thirteen inches long, and the largest we have ever found, though not so neat in its pattern as some others of an inferior size which have been engraved in our work. These were accompanied by a curious article of gold, which conceive had originally decorated the case of the dagger, Tumuli Plate XXVII, No. 1. The handle of wood belonging to this instrument, No. 2, exceeds any thing we have yet seen, both in design and execution, and could not he surpassed (if indeed equalled) by the most able workman of modern times. By the annexed engraving, you will immediately recognize the British zigzag, or the modern Vandyke pattern, which was formed with a labour and exactness almost unaccountable, by thousands of gold rivets, smaller than the smallest pin. The head of the handle, though exhibiting no variety of pattern, was also formed by the same kind of studding. So very minute, indeed, were these pins, that our labourers had thrown out thousands of them with their shovel, and scattered chem in every direction, before, by the necessary aid of a magnifying glass, we could discover what they were; but fortunately enough remained attached to the wood to enable us to develop the pattern. Beneath the fingers of the right hand lay a lance-head of brass, but so much corroded that it broke to pieces on moving. Immediately over the breast of the skeleton was a large plate of gold, Tumuli Plate XXVI. in the form of a lozenge, and measuring 7 inches by 6. It was fixed to a thin piece of wood, over the edges of which the gold was lapped: it is perforated at top and bottom, for the purpose, probably, of fastening it to the dress as a breast-plate. The even surface af this noble ornament is relieved by indented lines, checques, and zigzags, following the shape of the, outline, and forming lozenge within lozenge, diminishing gradually towards the centre. We next discovered, on the right side of the skeleton, a very curious perforated stone, some wrought articles of bone, many small rings of the same material, and another article of gold Plate XXVII, No 3, 4, 5. The stone is made out of a fossil mass of tubularia, and polished; rather of an egg form, or as a farmer who was present, observed, resembling the top of a large gimlet. It had a wooden handle, which was fixed into the perforation in the centre, and encircled by a neat ornament of brass, part of which still adheres to the stone. As this stone bears no marks of wear or attrition, I can hardly consider it to have been used as a domestic implement, and from the circumstance of its being composed of a mass of seaworms, or little serpents, I think we may not be too fanciful in considering it an article of consequence. We know, by history, that much importance was attached by the ancients to the serpent, and I have before had occasion to mention the veneration with which the glain nadrogth. was esteemed by the Britons; and my classical readers will recollect the fanciful story related by Pliny on this subject, who says, that the Druid's egg was formed by the scum of a vast multitude of serpents twisted and conjured up together. This stone, therefore, which contains a mass of or little serpents, might have been held in great veneration by the Britons, and considered of sufficient importance to merit a place amongst the many rich and valuable relicks deposited in this tumulus with the body of the deceased.

1. The word CELT has been applied to instruments of a very different form as well as composition, and has been written, engraved, and published concerning them. In the fifth volume of the Archæologia, we find a dissertation on them by Mr. Lort. accompanied by numerous engravings describing their different forms, some few of which resemble those that we have discovered; but one only is recorded a having been found in a Long barrow near Stonehenge by Dr. Stukeley, and rot recorded as a certainty. Much conjecture and debate have been employed by various authors respecting the original use of this instrument. Mr. Thoresby, in a letter to the celebrated antiquary Thomas Hearne, supposes them to have been heads of spears: or walking staves of the civilized Britons; but this opinion is rejected by Hearne, who thinks they were chissels used b the Romans for cutting and polishing stones. A curious inscription at Pola, in Istria, ascertains hat the word celtis denoted a chissel or graving tool, "Neque hic atramentum, vel papyrus, aut membrana ulla adhuc, sed malleolo et celie literatus silex, [Cruterus page 329]. Dr. Borlase also, in his Antiquities of Cornwall, page 281, has given an account of several brass Celts found in that county, together with an engraving. He supposes them to have been offensive weapons, and to have been made and used by the Romanized Britons. Dr. Stukeley attaches a degree of religious authority to them, by supposing that they were used by the Druids for cutting the mistletoe. These instruments differed in their construction, and in point of antiquity, l must give the priority of age to those discovered in our barrows, of which I am enabled to produce four specimens. The first engraved ia Tumuli Plate XXI is highly interesting, and shews the mode which the brass instrument was inserted in the handle. The second, engraved in Plate XXVI. is of a much larger size, but also had its handle; as well as two others engraved in subsequent plates, which, though smaller, resemble the others in form. I am obliged, from conviction, and from the strong evidence afforded by this handle, to differ from the learned antiquaries who have delivered their opinions on this subject. I cannot, with Mr. Thoresby and Dr. Borlase. suppose them to have been spear-heads, or offensive weapons; neither can I agree with the laborious antiquary, Thomas Hearne, in supposing them edge-tools for cutting stones, the metals of which they are formed are soft for such a purpose; neither can we find the edges furrowed and scratched by hard usage; nor can my antiquarian zeal and enthusiasm persuade me to coincide, in this instance, with the Druidical system of Dr, Stukeley. They appear to me to have been instruments used for domestic, not for mihitary, architectural, or purposes. These appear also to have been the first models, from which the pattern with sockets for the insertion of a handle was taken; for amongst the numerous specimens described by Mr. Lort in the Archæologia, not one of the latter pattern is mentioned as having been discovered in a barrow. As many similar instruments have been found in Gaul, and have been noticed by and Caylus, I cannot attribute the sole manufacture of them to Britain, but rather suppose they imported thither from the mother country on the continent; or perhaps the art of making them might have been introduced. One circumstance, I think, appears evident and conclusive viz. that the earliest pattern, and which probably gave rise to the larger and more ornamented one, was that described in four instances as having been discovered amongst other sepulchral deposits in British tumuli. The celts of flint, engraved in Tumuli PlateS V, VI. were evidently used for chipping stone or other materials, of which I can adduce a curious proof, by the circumstances attending discovery of one of these articles, which is now in my possession. Some workmen in cutting a canal, near Stockbridge, found several of these flint Celts dispersed about the soil, and deposited near the rude trunk af a tree, which was intended to have been fashioned by their means into a boat or canoe.

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 21 [Map] [Note. This appears to continue the previous mistake and number 20 as 21?] is a wide and low tumulus, over which the plough has performed its agricultural rites for many years. The mode of interment was here varied, and the very rich and numerous trinkets discovered in this barrow, seem to announce the skeleton to have been that of some very distinguished British female. The most remarkable of these, and unique in size, though not in pattern, was an ornament of amber, similar to that before engraved in Tumuli Plate III. but far exceeding it in all its proportions, being ten inches in height and above three in breadth; it is formed of eight instead of six distinct tablets, and by being strung together, formed one ornament, as may be distinctly seen by the perforations at top and bottom. Besides the above were numerous beads of amber of much larger proportions than usual, and varying in their patterns, four articles of gold perforated, perhaps for ear-rings, and two small earthen cups, the one about seven or eight inches deep, the other little above an inch. The largest of the beads, the gold ornaments, and the fragment of the smallest cup are engraved of their full size in Tumuli Plate XXXI.

Colt Hoare 1812. [No. 28 [Map]]"In the year 1723, by Thomas Earl of Pembroke's order, I begun upon a barrow north of Stonehenge, in that group south of the Cursus. It is one of the double barrows there, and the more easterly and lower of the two; likewise somewhat less. It was reasonable to believe, thig was the sepulture of and that the lesser was the female; and so it proved; at man and his wife; least a daughter. We made a large cut on the top, from east to west, and after the turf was taken off, we came to the layer of chalk, then to fine garden mould. About three teet below the surface was a layer of flints, humouring the convexity of the barrow. These flints are gathered from the surface of the downs in some places, especially where it has been ploughed. This being about a foot thick, rested on a layer of soft mould another foot, in which was enclosed an urn full of bones. The urn was of unbaked clay, of a dark reddish colour, and crumbled into pieces. It had been rudely wrought with small mould5ngs round the verge, and other circular channels on the outside, with several indentures between, (see Plate XXXII. where have drawn things made with a pointed tool, found in this barrow.) The bones had been burned, and crowded all together in a little heap, not so much as a hat crown would contain. The collar-bone, and one side of the under-jaw, are graved in their true magnitude. It appears have been a girl of about 14 years old, by their bulk, and the great quantity of female ornaments mixed with the bones, all which we gathered. Beads of all sorts, and in great number, of glass of divers colours, most yellow, one black; many single, many in long pieces notched between, so as to resemble a string of beads, and these were generally of a blue colour. There were many of amber, of all shapes and sizes; flat squares, long squares, round, oblong, and great. Likewise many of earth, of different shapes, magnitude, and colour; some little and white, many large and flattish like a button, others like a pully; but all had holes to run a string through, either through their diameter, or sides. Many of the button sort seem to have been covered with metal, there being a rim worked in them, wherein to turn the edge of the covering. One of these was covered with a thin film of pure gold. These were the young lady's ornaments; and alt had undergone the fire, so that what would easily consume, fell to pieces as soon as handled; much of the amber was burned half through. This person was a heroine, for we found the head of her javelin in brass. At bottom me two holes for the pins that fastened it to the staff. Besides, there was a sharp bodkin, round at one end, square at the other, where it went into a handle. I still preserve whatever is permanent of these trinkets; but we recomposed the ashes of the illustrious defunct, and covered them with earth, leaving visible marks at cop, of the barrow having been opened, to dissuade any other from again disturbing them; and this was our practice in all the rest."

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 156 [Map] is a fine bell-shaped barrow, 102 feet in base diameter, and 10 feet in elevation above the plain. It contained within a very shallow cist, the remains of a skeleton, whose head was placed towards the west, and a deposit of the most various elegant little trinkets; the most remarkable of which are two gold beads, engraved of their original size in Tumuli Plate XXV. No. 7, 8. The first is of an oblong form, large, and ornamented with circular rings; the other is much less, and of a globular; they appear to have been formed by first making a wooden bead, and then covering it with two thin plates of gold, which were overlapped in the centre, and made fast by indentation; for in none of these golden articles have we ever distinguished any marks of solder, or any other mode of fastening than by indentation. The large bead is perforated lengthways, the smaller one in two places on one side. Besides these beads of gold. there were several trinkets of jet, amber, &c. viz. a flat: piece of amber, No, 9; two other pieces, the one plain, the other marked with transverselines, both perforated; also two round beads of amber; a jet bead of a globular form, but much compressed, No. 10; another with convoluted stripes, No. 1; an article of jet, singular in its shape, No. 12; and some curious beads of stone, one of which, No. 13, seems to be the joint of a petrified echinus [sea urchin]. Besides the above articles, the most remarkable of which are engraved in Tumuli Plate XXV. we found another beautiful little grape cup, similar to those before described in Tumuli PlateS XI. and XXIV. in high preservation. There was also a drinking cup placed at the feet of the skeleton, which was unfortunately broken, but afterwards repaired.

Colt Hoare 1812. No. 155 [Map] is a fine bell-shaped barrow, 92 feet in diameter, and 11 in elevation, On the floor we found a large quantity of burned bones, and with them an earthen cup of a very singular and novel pattern, a cone of gold similar to the one discovered in the Golden barrow at Upton Lovel [Map], five other articles of gold, and several curious ornaments of amber. The cup was unfortunately mutilated on one side by the pressure of incumbent earth, but its size and pattern will be sufficiently described by the annexed engraving, Tumuli Plate XXV. Aa enthusiastic antiquary, who was present at the opening of this barrow, fancied that he could trace in this cup a design taken from the outward circle of Stonehenge. The elegant cone of gold, No I, is ornamented at intervals with four circular indentations, which are all dotted with a pointed instrument, in the same manner as the lines on our British pottery, but none of the intervals of these circular lines are filled up with the zigzag ornament, as in the gold cone found at Upton [Map]. The base of the cone is covered with a place, which is also ornamented with indented circular lines, and is made to overlap the lower edge of the cone, to which it is fastened: it is perforated at bottom in two places for the purpose of suspension. The outward plate of thin, but pure, gold, is supported by a cone of blackish wood, on which the indentations correspond exactly with those on the outward cone. The horn like ornament, No. 2, is made of brass, but covered with thin plate of gold: two holes the broad part of it, seem to indicate that this also was an ornament of decoration, and worn by suspension; and from the position of the perforations in each of these articles, we might suppose they were worn with their points downwards. The two circular trinkets, No. 3, are extremely beautiful, and in high preservation; they are composed of red amber set round with gold, and are also perforated for suspension: they bear a very strong resemblance to some articles found by Dr. Stukeley in a barrow, north of Stonehenge, and engraved in TAB. XXXll. where he describes them as being of earth covered with gold. In No. 4, we see another trinket of red amber, decorated with fluted stripes of gold, and having the usual perforations: a thin bit of brass still adheres to it, and which appears to have been fastened to the amber by two rivets. No, 5 is a checquered plate of gold laid over a piece of polished bone. On first sight of this article we might be led to suppose that the hole on the cop had been made for the purpose of suspension, but on a close examination of it, we evidently see that the points never joined; and the holes for stringing are on the back part. Besides these various ornaments of gold, there were several articles of deep-coloured amber, and of a novel shape, No. 6. No barrow that we have yet opened has ever produced such a variety of singular and elegant articles, for except the cone of gold, all are novelties, both in pattern and design.

Nænia Cornubiæ by William Borlase Introductory Preface. In the course of the following essay, it must be understood that no monuments are mentioned, unless incidentally, but those in which either interments have actually occurred, or where a sepulchral origin is placed beyond doubt by their form, or by a comparison with similar remains in the same or a kindred district. The objects engraved are also, almost invariably, those discovered in close proximity to the interments. Barrows and Cairns, however, are by no means the most fruitful field for Cornish Antiquities.1 Tin stream-works, and the sites of ancient mines and smelting-houses, have been always the most productive source of objects of interest to the Cornish Antiquary; and a paper of considerable length and no little interest might be written on the subject of the implements, weapons, and ornaments of the ancient miners of the West.2 With these, however, the present treatise has nothing to do; and it will be sufficient at present for the reader to discover that the promise held out by the title of this little volume has been very incompletely fulfilled. Of this the author is well aware. Much remains to be done; nooks and corners in the county there are, which still require investigation; but, should these pages meet with the reader's approbation, the author of them can only add that he intends to continue his researches, and to embody in a second series, not only the unpublished accounts of several other barrows already explored by him, but also the details of any more, which he may be so fortunate as to obtain permission to investigate.

Note 1. Two gold lunulæ were, indeed, found in a mound of earth near Padstow, but not in connection with any sepulchral remains. The only instance where that precious metal has occurred actually with human bones will be duly described in the sequel.

Note 2. Carew mentions that in the stream-works are found "little tools heads of brass, which some term thunder axes." Besides these celts, bronze spear-heads, arrow-heads, ornaments of gold, and jet, &c., &c. are among the objects not unfrequently dug up in the "old men's workings."

Bush Barrow aka Normanton 158 aka Wilsford G5 [Map] is a Bronze Age Round Barrow. In 1808 Bush Barrow aka Normanton 158 aka Wilsford G5 [Map] was excavated by William Cunnington. It contained a male skeleton with a collection of funerary goods that make it one of the richest burials in Britain. The grave goods include a large 'lozenge'-shaped sheet of gold, a sheet gold belt plate, three bronze daggers, a bronze axe, a stone macehead and bronze rivets.

All the following items are in the collection of [Map] and normally on display. The photographs and information is sourced from Devizes Museum website.

Bronze flanged axehead with traces of coarse cloth visible on the blade, found with a primary male inhumation (near the shoulders). Length 159 mm; width 67 mm; height 10 mm.

Gold lozenge-shaped breast plate made of thin gold covering a wooden plaque and decorated with four nested lozenge-shaped bands of four engraved lines each, the central one of which contains a chequered design with a zigzag design between the outer two bands, perforated at both ends, found with a primary male inhumation (over chest). Length 184 mm; width 156 mm; height 5 mm.

Polished oval macehead made from a fossil coral, perforated through the middle and containing traces of bronze. Found with a male inhumation (by right side) and possibly forming a sceptre. Length 100 mm; width 44 mm; height 40 mm.

Miniature gold lozenge-shaped ornament decorated with three nested lozenge-shaped lines (engraved), found with a primary male inhumation (by right side). Length 31 mm; width 19 mm; height 2 mm.

Copper dagger (Amorico British Class 1a) with a small tang, six rivets and parts of a wooden sheath adhering to the blade (originally with a handle inset with thousands of gold pins), found with a primary male inhumation (near right arm). Length 272 mm; width 80 mm; height 21 mm.

Gold belt hook decorated with four nested rectangular bands of three engraved lines, found with a primary male inhumation (near right arm). Length 77 mm; width 71 mm; height 16 mm.

Bronze dagger (the largest found in Wiltshire) with 6 rivet holes (three remaining) and parts of a wooden sheath adhereing to the blade, decorated with a rounded ridge. Length 330 mm; width 65 mm; height 20mm.