On this Day in History ... 21st January

21 Jan is in January.

1536 Death of Catherine of Aragon

1536 Funeral of Catherine of Aragon

1560 Consecration of new Bishops

Events on the 21st January

On 21 Jan 1264 Alexander Dunkeld Prince Scotland was born to Alexander III King Scotland (age 22) and Margaret Queen of Scotland (age 23) at Jedburgh. He a grandson of King Henry III of England.

Chronicle of Gregory 1437. 21 Jan 1437. And that year the King (age 15) ordaynyde the Parlyment to be holde at Cambridge [Map] Caumbryge, but aftyr warde by goode counselle it was tornyde and holde att Westemyster; the whyche Parlyment be ganne the xxj day of Janyver. And to that Parlyment come the Byschoppe of Tyrwynne [Thérouanne] ande the counselle of the Erle of Armanacke (age 40).

Letters 1536. 21 Jan 1536. Vienna Archives. 141. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

Great preparation is made for the Queen's burial, which, as Cromwell sent to inform me, will be so magnificent that even those who see it all will hardly believe it. It is to take place on the 1st February. The chief mourner will be the King's niece (age 17), daughter of the Duke of Suffolk (age 52); the Duchess of Suffolk (age 16) will be the second; the third will be the wife of the Duke of Norfolk's son. of others there will be a great multitude; I think they mean to dress in mourning about 600 persons. Nothing is said yet of the lords who are to be present. Cromwell again, since I wrote to your Majesty, has twice sent to press on my acceptance the mourning cloth which the King wished to give me, and would gladly by this means bind me to be present at the interment, which the King greatly desires, but following the advice of the Queen Regent in Flanders, of the Princess, and of several good personages, I will not go, since they do not mean to bury her as Queen. I have refused the said cloth, saying simply that I did not do it of any ill intention, but only because I was already provided. The King had intended, or those of his Council, that solemn exequies should be made at the Cathedral Church of this city, and a number of carpenters and others had already been set to work to make preparations, but, since then, the whole thing has been broken off; I do not know if it was ever sincerely intended, or if it was only a pretence for the satisfaction of the people, to remove sinister opinions.

Calendars. 21 Jan 1536. Eustace Chapuys (age 46) to the Emperor (age 35).

The good Queen (deceased) breathed her last at 2 o'clock in the afternoon. Eight hours afterwards, by the King's (age 44) express commands, the inspection of her body was made, without her confessor or physician or any other officer of her household being present, save the fire-lighter in the house, a servant of his, and a companion of the latter, who proceeded at once to open the body. Neither of them had practised chirurgy, and yet they had often performed the same operation, especially the principal or head of them, who, after making the examination, went to the Bishop of Llandaff, the Queen's confessor, and declared to him in great secrecy, and as if his life depended on it, that he had found the Queen's (deceased) body and the intestines perfectly sound and healthy, as if nothing had happened, with the single exception of the heart, which was completely black, and of a most hideous aspect; after washing it in three different waters, and finding that it did not change colour, he cut it in two, and found that it was the same inside, so much so that after being washed several times it never changed colour. The man also said that he found inside the heart something black and round, which adhered strongly to the concavities. And moreover, after this spontaneous declaration on the part of the man, my secretary having asked the Queen's physician whether he thought the Queen (deceased) had died of poison, the latter answered that in his opinion there was no doubt about it, for the bishop had been told so under confession, and besides that, had not the secret been revealed, the symptoms, the course, and the fatal end of her illness were a proof of that.

No words can describe the joy and delight which this King (age 44) and the promoters of his concubinate (age 35) have felt at the demise of the good Queen (deceased), especially the earl of Vulcher (age 59), and his son (age 33), who must have said to themselves, What a pity it was that the Princess (age 19) had not kept her mother (deceased) company. The King (age 44) himself on Saturday, when he received the news, was heard to exclaim, "Thank God, we are now free from any fear of war, and the time has come for dealing with the French much more to our advantage than heretofore, for if they once suspect my becoming the Emperor's friend and ally now that the real cause of our enmity no longer exists I shall be able to do anything I like with them." On the following day, which was Sunday, the King (age 44) dressed entirely in yellow from head to foot, with the single exception of a white feather in his cap. His bastard daughter (age 2) was triumphantly taken to church to the sound of trumpets and with great display. Then, after dinner, the King (age 44) went to the hall, where the ladies were dancing, and there made great demonstration of joy, and at last went into his own apartments, took the little bastard (age 2), carried her in his (age 44) arms, and began to show her first to one, then to another, and did the same on the following days. Since then his joy has somewhat subsided; he has no longer made such demonstrations, but to make up for it, as it were, has been tilting and running lances at Grinduys [Map]. On the other hand, if I am to believe the reports that come to me from every quarter, I must say that the displeasure and grief generally felt at the Queen's (deceased) demise is really incredible, as well as the indignation of the people against the King (age 44). All charge him with being the cause of the Queen's (deceased) death, which I imagine has been produced partly by poison and partly by despondency and grief; besides which, the joy which the King (age 44) himself, as abovesaid, manifested upon hearing the news, has considerably confirmed people in that belief.

Great preparations are being made for the burial of the good Queen (deceased), and according to a message received from Master Cromwell (age 51) the funeral is to be conducted with such a pomp and magnificence that those present will scarcely believe their eyes. It is to take place on the 1st of February; the chief mourner to be the King's own niece (age 18), that is to say, the daughter of the duke of Suffolk (age 52); next to her will go the Duchess, her mother; then the wife of the duke of Norfolk (age 39), and several other ladies in great numbers. And from what I hear, it is intended to distribute mourning apparel to no less than 600 women of a lower class. As to the lords and gentlemen, nothing has yet transpired as to who they are to be, nor how many. Master Cromwell (age 51) himself, as I have written to Your Majesty (age 35), pressed me on two different occasions to accept the mourning cloth, which this King (age 44) offered for the purpose no doubt of securing my attendance at the funeral, which is what he greatly desires; but by the advice of the Queen Regent of Flanders (Mary), of the Princess herself, and of many other worthy personages, I have declined, and, refused the cloth proffered; alleging as an excuse that I was already prepared, and had some of it at home, but in reality because I was unwilling to attend a funeral, which, however costly and magnificent, is not that befitting a Queen of England.

The King (age 44), or his Privy Council, thought at first that very solemn obsequies ought to be performed at the cathedral church of this city. Numerous carpenters and other artizans had already set to work, but since then the order has been revoked, and there is no talk of it now. Whether they meant it in earnest, and then changed their mind, or whether it was merely a feint to keep people contented and remove suspicion, I cannot say for certain.

Letters 1536. 21 Jan 1536. Vienna Archives. 141. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

You could not conceive the joy that the King and those who favor this concubinage have shown at the death of the good Queen, especially the earl of Wiltshire (age 59) and his son (age 33), who said it was a pity the Princess (age 19) did not keep company with her. The King, on the Saturday he heard the news, exclaimed "God be praised that we are free from all suspicion of war"; and that the time had come that he would manage the French better than he had done hitherto, because they would do now whatever he wanted from a fear lest he should ally himself again with your Majesty, seeing that the cause which disturbed your friendship was gone. On the following day, Sunday, the King was clad all over in yellow, from top to toe, except the white feather he had in his bonnet, and the Little Bastard (age 2) was conducted to mass with trumpets and other great triumphs. After dinner the King entered the room in which the ladies danced, and there did several things like one transported with joy. At last he sent for his Little Bastard (age 2), and carrying her in his arms he showed her first to one and then to another. He has done the like on other days since, and has run some courses (couru quelques lances) at Greenwich.From all I hear the grief of the people at this news is incredible, and the indignation they feel against the King, on whom they lay the blame of her death, part of them believing it was by poison and others by grief; and they are the more indignant at the joy the King has exhibited. This would be a good time, while the people are so indignant, for the Pope to proceed to the necessary remedies, by which these men would be all the more taken by surprise, as they have no suspicion of any application being made for them now that the Queen is dead, and do not believe that the Pope dare take upon him to make war especially while a good part of Germany and other Princes are in the same predicament. Nevertheless, now that the Queen is dead, it is right for her honor and that of all her kin that she be declared to have died Queen, and it is right especially to proceed to the execution of the sentence, because it touches the Princess, and to dissolve this marriage which is no wise rendered valid by the Queen's death, and, if there be another thing, that he cannot have this woman to wife nor even any other during her life according to law, unless the Pope give him a dispensation; and it appears that those here have some hope of drawing the Pope to their side, for only three days ago Cromwell said openly at table that a legate might possibly be seen here a few days hence, who would come to confirm all their business, and yesterday commands were issued to the curates and other preachers not to preach against purgatory, images, or adoration of the saints, or other doubtful questions until further orders. Perhaps by this means and others they hope to lull his Holiness to sleep until your Majesty has parted from him, which would be a very serious and irremediable evil. I think those here will have given charge to the courier, whom they despatched in great haste to give the news of the Queen's death in France, to go on to Rome in order to prevent the immediate publication of censures.

Letters 1536. 21 Jan 1536. The Queen (deceased) died two hours after midday, and eight hours afterwards she was opened by command of those who had charge of it on the part of the King, and no one was allowed to be present, not even her confessor or physician, but only the candle-maker of the house and one servant and a "compagnon," who opened her, and although it was not their business, and they were no surgeons, yet they have often done such a duty, at least the principal, who on coming out told the Bishop of Llandaff, her confessor, but in great secrecy as a thing which would cost his life, that he had found the body and all the internal organs as sound as possible except the heart, which was quite black and hideous, and even after he had washed it three times it did not change color. He divided it through the middle and found the interior of the same color, which also would not change on being washed, and also some black round thing which clung closely to the outside of the heart. On my man asking the physician if she had died of poison he replied that the thing was too evident by what had been said to the Bishop her confessor, and if that had not been disclosed the thing was sufficiently clear from the report and circumstances of the illness.

Letters 1536. 21 Jan 1536. Vienna Archives. 141. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

Now the King and Concubine (age 35) are planning in several ways to entangle the Princess in their webs, and compel her to consent to their damnable statutes and detestable opinions; and Cromwell was not ashamed, in talking with one of my men, to tell him you had no reason to profess so great grief for the death of the Queen, which he considered very convenient and advantageous for the preservation of friendship between your Majesty and his master; that henceforth we should communicate more freely together, and that nothing remained but to get the Princess to obey the will of the King, her father, in which he was assured I could aid more effectually than anybody else, and that by so doing I should not only gratify the King but do a very good office for the Princess, who on complying with the King's will would be better treated than ever. The Concubine (age 35), according to what the Princess sent to tell me, threw the first bait to her, and caused her to be told by her aunt, the gouvernante (age 60) of the said Princess, that if she would lay aside her obstinacy and obey her father, she would be the best friend to her in the world and be like another mother, and would obtain for her anything she could ask, and that if she wished to come to Court she would be exempted from holding the tail of her gown, "et si la meneroit tousjours a son cause" (?); and the said gouvernante (age 60) does not cease with hot tears to implore the said Princess to consider these matters; to which the Princess has made no other reply than that there was no daughter in the world who would be more obedient to her father in what she could do saving her honor and conscience.From what the Princess has sent to tell me, it seems probable that the King will shortly send to her a number of his councillors to summon her to give the oath. She requested me to notify to her what to reply, and I wrote that I thought she had best show as good courage and constancy as ever with requisite modesty and dignity (honesteté), for if they began to find her at all shaken they would pursue her to the end without ever leaving her in peace; and that I thought they would not insist very much on her renouncing her right openly, nor abjuring the authority of the Pope directly, but that they might press her to swear to the Concubine (age 35) as Queen, alleging that as the Queen was dead there could be no excuse for opposition. I wrote to her to use every effort to avoid any discussion with the King's deputies, beseeching them to leave her in peace that she might pray to God for the soul of the Queen, her mother, and also for His aid, and declaring that she was a poor and simple orphan without experience, aid, or counsel, that she did not understand laws or canons, and did not know how then to answer them; that she should also beseech them to intercede with the King, her father, to have pity on her weakness and ignorance; and, if she thought it necessary to say more, she might add that as it is not the custom to swear [fealty] here to Queens, and such a thing had not been done when her mother was held as Queen, she cannot but suspect that it would be directly or indirectly to her prejudice; also that if she (Anne Boleyn) was Queen, her swearing or refusing to swear did not matter, and likewise if she is not; and that she remembers well one thing,—that in the Consistorial sentence by which the first marriage had been declared valid, this second marriage was annulled, and it was declared that this lady could not claim the title of Queen, for which reason she thought in conscience that she could not go against the Pope's command, and that by so doing she-would prejudice her own right. I also suggested to the Princess that she might tell her gouvernante (age 60) it was but waste of time to press such matters upon her, because she would lose her life ten times before consenting to it without being better informed and her scruple of conscience removed by other persons than those of this realm whom she held "suspects," and that, if the King, her father, would give her time till she came "en eaige de perfection," from which she was perhaps not far removed, God would inspire her to devote herself entirely to him and enter religion, in which case she considers her honor and conscience might be preserved; or she might be meanwhile otherwise informed;—that this delay could be no disadvantage to the King, her father, but rather the contrary, for if she came to consent to matters the act at such an age would be of more validity. This I wrote to her, not as a positive instruction, but only as matter for consideration. I will think more at large of other means for putting the matter off in case of extremity, but if they have determined to poison her (luy donner a manger), neither taking the Sacrament nor any other security that can be invented will be of much avail.

Letters 1536. 21 Jan 1536. Vienna Archives. 141. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

My man has sent me from Flanders, where the Queen has kept him some days, your Majesty's letters of the 13th ult., to which I must delay replying till his return. I thank you for writing that I shall not be forgotten when the time of distribution of benefices arrives. Must not omit to say that the enterprise mentioned in the said letters is becoming more difficult every day, especially since the death of the Queen (deceased), as they have kept more company than before ("lon a tenu plus de court et en plus de regard que par avant"). I have also received your Majesty's letters of the 29th, with your most prudent discourse touching the perplexity of the affairs of the late good Queen (deceased) and of the Princess (age 19), the substance of which considerations, though not so well put, has been already at times communicated to the said ladies. Moreover, I added another point, viz., that what was chiefly to be feared, if they were compelled to swear all that the King wished (besides the bad effect mentioned in your Majesty's letters, that so many would lose heart and join the new heresy), the danger would be, not that the King would proceed by law to punish daily disobedience, but that, under color of perfect reconciliation, if he were to treat them well,—I don't suppose the King but the Concubine (age 35) (who has often sworn the death of both, and who will never be at rest till she has gained her end, suspecting that owing to the King's fickleness there is no stability in her position as long as either of the said ladies lives), will have even better means than before of executing her accursed purpose by administering poison, because they would be less on their guard; and, moreover, she might do it without suspicion, for it would be supposed when the said ladies had agreed to everything that the King wished and were reconciled and favorably treated after they had renounced their rights, there could be no fear of their doing any mischief, and thus no suspicion would arise of their having received foul play.

The King and Concubine (age 35), impatient of longer delay, especially as they saw that proceedings were taken at Rome in good earnest, and that when your Majesty goes thither the provisions will be enforced, determined to make an end of the Queen's process, as you will see by what follows. It must have been very convenient for them that she died before the Princess, for several reasons, and, among others, because it was at her instance that proceedings were taken at Rome, and because they had less hope of being able to bring her over to their opinions, reckoning more upon her constancy by reason of age than on that of her daughter, especially because, not being naturally subject to their laws, they could not constrain her by justice as they could her daughter. Further, I think the cupidity which governs them has led them more to anticipate the death of the mother, as they will not be obliged to restore the dowry.

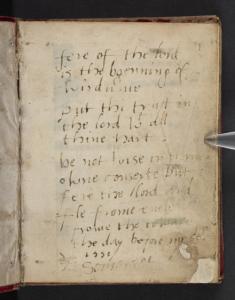

On 21 Jan 1551, the day before his execution, Edward Seymour 1st Duke of Somerset (age 51), wrote an inscription on the fly-leaf of an almanac: "Fere of the lord is the b[e]genning of wisdume, Put thi trust in the lord w[i]t[h] all thine hart, Be not wise in thyne owne conseyte but fere the lord and fle frome euele [evil], frome the toware, the day before my deth, 1551 [1552]". E: Somerset.

On 21 Jan 1560 two Bishops were consecrated ...

Bishop Nicholas Bullingham (age 40) was consecrated Bishop of Lincoln.

Archbishop Thomas Young (age 53) was consecrated Bishop of St David's at Lambeth Palace [Map] by Archbishop Matthew Parker (age 55).

Henry Machyn's Diary. 21 Jan 1560. The xxj day of January by ix of the cloke my lord mare (age 64) and the althermen whent by water to the cowrt in skarlett, and ther he was mad knyght by the quen (age 26).

On 21 Jan 1640 Mountjoy Blount 1st Earl Newport (age 43) participated with King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland (age 39) in the extravagant masque on the theme of Philogenes, royal Lover of the People.

Pepy's Diary. 21 Jan 1661. This morning Sir W. Batten (age 60), the Comptroller (age 50) and I to Westminster, to the Commissioners for paying off the Army and Navy, where the Duke of Albemarle (age 52) was; and we sat with our hats on, and did discourse about paying off the ships and do find that they do intend to undertake it without our help; and we are glad of it, for it is a work that will much displease the poor seamen, and so we are glad to have no hand in it. From thence to the Exchequer, and took £200 and carried it home, and so to the office till night, and then to see Sir W. Pen (age 39), whither came my Lady Batten and her daughter, and then I sent for my wife, and so we sat talking till it was late. So home to supper and then to bed, having eat no dinner to-day. It is strange what weather we have had all this winter; no cold at all; but the ways are dusty, and the flyes fly up and down, and the rose-bushes are full of leaves, such a time of the year as was never known in this world before here. This day many more of the Fifth Monarchy men were hanged.

Pepy's Diary. 21 Jan 1667. Here spoke with my Lord Bellasses (age 52) about getting some money for Tangier, which he doubts we shall not be able to do out of the Poll Bill, it being so strictly tied for the Navy. He tells me the Lords have passed the Bill for the accounts with some little amendments.

On 21 Jan 1674 Edward Bagot 4th Baronet was born to Walter Bagot 3rd Baronet (age 29) and Jane Salusbury.

On 22 Oct 1691 Lucius Knightley (age 68) died in Fawsley, Northamptonshire. On 21 Jan 1710 Elizabeth Dent (age 77) died. They were buried in St Mary's Church, Fawsley [Map].

Lucius Knightley: On 03 Apr 1623 he was born to Richard Knightley in Fawsley, Northamptonshire. Before 22 Oct 1691 Lucius Knightley and Elizabeth Dent were married.

Elizabeth Dent: On 02 Nov 1632 she was born.

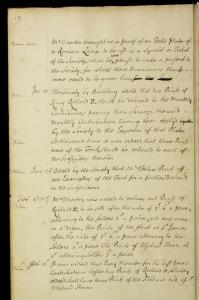

Minutes of the Society of Antiquaries. 21 Jan 1719. The Society by Balloting ordered that two prints of King Richard II should be delivered to the Monthly Contributors paying their Arrears the said Monthly Contribution having been applyed by the Society to the Expense of that Plate.

At the same time it was ordered that three Prints more of the Font should be delivered to each of the Subscribers thereto.

On 21 Jan 1793 Louis XVI King France (age 38) was guillotined in Paris [Map]. His son Louis XVII King France (age 7) de jure XVII King France: Capet Valois Bourbon.

On 21 Jan 1829 King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway was born to Oscar I King Sweden and Norway (age 29).

Archaeologia Volume 25 Section VI. Proclamation of Henry the Eighth on his Marriage with Queen Anne Boleyn; in the possession of the Corporation of Norwich: Communicated by Hudson Gurney, Esg. V.P., in a Letter to Henry Ellis (age 54), Esq., F.R.S., Secretary.

Read 29th March, 1832.

Keswick, January 21, 1832.

On 21 Jan 1845 Samuel Colman (age 65) died.

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1858. 21 Jan 1858. January 21. Holman Hunt (age 30) and Martineau called on me at 7 and stayed till nearly half-past 10. After desultory chat and looking at drawings, etc., Hunt introduced the subject which principally brought him. Having in prospect to marry Annie Miller (age 23), after that her education both of mind and manners shall have been completed, he wished to destroy as far as was possible all traces of her former occupation, viz, that of sitting to certain artists (those artists, however, being all his personal friends, Rossetti, A. Hughes, Stephens, Egg, Holliday, Millais, Collins and myself), and as mine was the only direct study of her head, as it was, he would hold it a favour if I would give it him and he in return would give me something of his doing that I might like. At first I resisted stoutly, but finding that it was a serious point with him, and that my refusing would be in some degree an obstacle in the carrying out of his wishes with regard to her (which it would be both selfish and unkind and foolish in the remotest degree to thwart) I at last reluctantly assented to give him the study, the most careful and the most interesting (to me) and which I prize the most I have ever made. He thanked me heartily for my com- pliance. He gave me real pleasure by telling me that she says I always behaved most kindly to her.

On 21 Jan 1869 John Tweed was born.

On 21 Jan 1876 Herbert Noble (age 19) died in a railway accident at Abbots Ripton. The Special Scotch Express train from Edinburgh to London was involved in a collision, during a blizzard, with a coal train. An express travelling in the other direction then ran into the wreckage.

On 21 Jan 1876 Isabella Williamson (age 42), and her two sons James Charles Allgood (age 13) and David Williamson Allgood (age 11) died in a railway accident at Abbots Ripton.

On 21 Jan 1902 James Nesfield Forsyth (age 38) and Cecilia Naylor (age 26) were married at All Saints Church in the presence of William Adam Forsyth (age 29) and James Forsyth (age 74). He the son of James Forsyth (age 74) and Eliza Hastie.

On 21 Jan 1912 Barbara "Baba" Beaton was born to Ernest Beaton (age 45) and Esther "Etty" Sisson (age 40).

After 21 Jan 1946. Monument to Warrant Office Basil Thomas Parsons. Royal Air Force Service Number: 357411. Son of Thomas and Jane Parsons; husband of A. Kenwyn E. (Bridget) Parsons, of Fulbeck. Passed away suddenly at Rauceby R.A.F. Hospital.

Births on the 21st January

On 21 Jan 1264 Alexander Dunkeld Prince Scotland was born to Alexander III King Scotland (age 22) and Margaret Queen of Scotland (age 23) at Jedburgh. He a grandson of King Henry III of England.

On 21 Jan 1300 Roger Clifford 2nd Baron Clifford was born to Robert Clifford 1st Baron Clifford (age 25) and Maud Clare Baroness Clifford Baroness Welles (age 24).

On 21 Jan 1352 John Berkeley was born to Thomas Rich Berkeley 8th and 3rd Baron Berkeley (age 56) and Katherine Clivedon Baroness Berkeley (age 42) at Corston, Leicestershire.

On 21 Jan 1430 Thomas Grenville was born to William Grenville (age 43).

On 21 Jan 1441 Thomas Windsor was born.

On 21 Jan 1568 Catherine Gonzaga Duchess Longueville was born to Louis Gonzaga Duke Nevers (age 28).

On 21 Jan 1579 Mary Herbert was born to Henry Herbert 2nd Earl Pembroke (age 41) and Mary Sidney Countess Pembroke (age 17).

On or before 21 Jan 1586, the date he was baptised, William Eure of Bradley in County Durham was born to William Eure 2nd Baron Eure (age 56) and Margaret Dymoke.

On 21 Jan 1630 John Bourchier was born to Edward Bourchier 4th Earl Bath (age 39) and Dorothy St John Countess Bath. Coefficient of inbreeding 1.56%.

On 21 Jan 1641 Jane Hastings was born to Henry Hastings (age 35) and Jane Goodall.

On or before 21 Jan 1648 John Coryton 2nd Baronet was born to John Coryton 1st Baronet (age 26) and Elizabeth Mills Lady Coryton. He was baptised on 21 Jan 1648 at St Melanus' Church, St Mellion.

On 21 Jan 1661 Peter Le Neve was born to Francis Le Neve and Avice Wright.

On 21 Jan 1674 Edward Bagot 4th Baronet was born to Walter Bagot 3rd Baronet (age 29) and Jane Salusbury.

On 21 Jan 1677 Agmondisham Vesey was born to Archbishop John Vesey (age 38) and Anne Muschamp (age 27).

On 21 Jan 1702 Dorothea Franziska Agnes Salm was born to Louis Otto Salm Count Salm Salm (age 27) and Albertine Johannette Nassau Hadamar Countess Salm (age 27). She a great x 3 granddaughter of King James I of England and Ireland and VI of Scotland.

Before 21 Jan 1717 Henry John Carey was born to Lucius Carey 6th Viscount Falkland (age 29) and Dorothy Molyneux Viscountess Falkland.

On 21 Jan 1719 Reverend John Coleridge was born.

On 21 Jan 1721 Frances Lee was born to George Henry Lee 2nd Earl Lichfield (age 30) and Frances Hales Countess Lichfield (age 24). She a great granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Jan 1732 Frederick Eugene Württemberg Duke Württemberg was born.

On 21 Jan 1733 William Digby was born to Edward Digby (age 40).

On 21 Jan 1746 Elizabeth Venables-Vernon Countess Harcourt was born to George Venables-Vernon 1st Baron Vernon (age 36) and Martha Harcourt Baroness Vernon of Kinderton (age 30).

On 21 Jan 1750 William Ward 3rd Viscount Dudley and Ward was born to John Ward 1st Viscount Dudley and Ward (age 45).

On 21 Jan 1750 Algernon Percy 1st Earl Beverley was born to Hugh Percy 1st Duke Northumberland (age 34) and Elizabeth Seymour Duchess Northumberland (age 33).

On 21 Jan 1764 Catherine Anguish Duchess Leeds was born to Thomas Anguish of Great Yarmouth.

On 21 Jan 1769 Charlotta Louisa Lawless was born to Nicholas Lawless 1st Baron Cloncurry (age 33) and Margaret Browne Baroness Cloncurry (age 33).

On 21 Jan 1772 Amelia Hume Baroness Farnborough was born to Abraham Hume 2nd Baronet (age 22) and Amelia Egerton (age 20) at Wormley, Hertfordshire.

On 21 Jan 1796 Marie Wilhelmine Friederike Hesse-Kassel was born to Frederick Hesse-Kassel (age 48). She a great granddaughter of King George II of Great Britain and Ireland.

On 21 Jan 1800 William Aloysius Clavering 9th Baronet was born to Thomas John Clavering 8th Baronet (age 28).

On 21 Jan 1811 James Hamilton 1st Duke of Abercorn was born to James Hamilton (age 24) and Harriet Douglas Countess Aberdeen (age 18) at Seymour Place.

On 21 Jan 1823 George Hans Hamilton was born.

On 21 Jan 1829 King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway was born to Oscar I King Sweden and Norway (age 29).

On 21 Jan 1855 Ralph Ormsby-Gore 3rd Baron Harlech was born to William Richard Ormsby-Gore 2nd Baron Harlech (age 35) and Emily Charlotte Seymour-Conway Baroness Harlech.

On 21 Jan 1859 Walter Yarde-Buller was born to John Yarde-Buller (age 35) and Charlotte Chandos-Pole (age 29).

On 21 Jan 1861 Ramón Santamarina Alduncín was born to Ramón Santamarina Valcárcel (age 33) at Tandil.

On 21 Jan 1861 Henry Foley Lambert aka Grey 7th Baronet was born to Henry Lambert 6th Baronet (age 38).

On 21 Jan 1869 John Tweed was born.

On 21 Jan 1871 Henry Algernon George Percy was born to Henry George Percy 7th Duke Northumberland (age 24) and Edith Campbell Duchess Northumberland (age 21).

On 21 Jan 1878 George Vivian 4th Baron Vivian was born to Hussey Vivian 3rd Baron Vivian (age 43) at Connaught Place, Bayswater.

On 21 Jan 1888 Philip Morton Shand was born to Alexander Faulkner Shand (age 29) and Augusta Mary Coates (age 28).

On 21 Jan 1892 Rachel Beatrice Lyttelton Lady Riddell was born to Charles Lyttelton 8th Viscount Cobham (age 49) and Mary Susan Cavendish Viscountess Cobham (age 38)

On 21 Jan 1912 Barbara "Baba" Beaton was born to Ernest Beaton (age 45) and Esther "Etty" Sisson (age 40).

On 21 Jan 1940 Henry Robin Ian Russell 14th Duke Bedford was born to John Ian Robert Russell 13th Duke Bedford (age 22) and Clare Bridgman (age 37) at Ritz Hotel.

On 21 Jan 1955 Anne Mary Somerset was born to David Fitzroy 11th Duke Beaufort (age 26) and Caroline Jane Thynne 11th Duchess Beaufort (age 27).

Marriages on the 21st January

On 21 Jan 1561 Thomas Smith of Hough in Cheshire (age 16) and Anne Brereton (age 14) were married.

Before 21 Jan 1661 Francis Le Neve and Avice Wright were married.

On 21 Jan 1690 Gregory Page 1st Baronet (age 21) and Mary Trotman Lady Turner (age 18) were married.

On 21 Jan 1730 Charles Willing (age 19) and Anne Shippen (age 19) were married.

Before 21 Jan 1772 Abraham Hume 2nd Baronet (age 22) and Amelia Egerton (age 20) were married. She the daughter of Bishop John Egerton (age 50) and Anne Sophia Grey.

On 21 Jan 1890 Alistair George Hay and Camilla Dagmar Violet Greville (age 24) were married. They divorced in 1908. He the son of George Hay-Drummond 12th Earl Kinnoull (age 62) and Emily Blanche Charlotte Somerset Countess Kinnoul (age 62).

On 21 Jan 1891 Henry Fitzgerald (age 27) and Inez Charlotte Grace Boteler were married at Taplow, Buckinghamshire [Map]. He the son of Charles William Fitzgerald Fitzgerald 4th Duke Leinster and Caroline Leveson-Gower Duchess Leinster. He a great x 5 grandson of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Jan 1902 James Nesfield Forsyth (age 38) and Cecilia Naylor (age 26) were married at All Saints Church in the presence of William Adam Forsyth (age 29) and James Forsyth (age 74). He the son of James Forsyth (age 74) and Eliza Hastie.

On 21 Jan 1904 Reginald Herbert 15th Earl Pembroke 12th Earl Montgomery (age 23) and Beatrice Eleanor Paget Countess Pembroke and Montgomery (age 20) were married. He the son of Sidney Herbert 14th Earl Pembroke 11th Earl Montgomery (age 50) and Beatrix Louisa Lambton Countess Pembroke and Montgomery (age 45). They were third cousin once removed.

On 21 Jan 1908 Douglas Halyburton Cairns and Constance Anne Montagu-Douglas-Scott (age 30) were married. She the daughter of William Scott 6th Duke Buccleuch 8th Duke Queensberry (age 76) and Louisa Jane Hamilton Duchess Buccleuch and Queensbury (age 71). She a great x 5 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

Deaths on the 21st January

Florence of Worcester Continuation. 21 Jan 1140. Thurstan, Archbishop of York, retires to Pontefract. Thurstan (age 70), the twenty-sixth archbishop of York in succession, a man advanced in years and full of days, put off the old man and put on the new, retiring from worldly affairs, and becoming a monk at Pontefract, on the twelfth of the ides of February (21st January), and departing this life in a good old age, on the nones [the 5th] of February, he lies buried there.

On 21 Jan 1254 Godfrey Reginar (age 45) died.

On 21 Jan 1397 Albert Wittelsbach II Duke Bavaria Straubing (age 28) died.

On 21 Jan 1398 Frederick Hohenzollern V Burgrave Nuremburg (age 64) died. His son John Hohenzollern Burgrave Nuremburg (age 29) succeeded III Burgrave Nuremberg.

On 21 Jan 1426 Siemowit IV Duke of Masovia (age 73) died.

On 21 Jan 1495 Magdalena Valois Countess Foix (age 51) died.

On 21 Jan 1524 Alexander Gordon 3rd Earl Huntley died at Perth [Map]. His grandson George Gordon 4th Earl Huntley (age 10) succeeded 4th Earl Huntley.

On 21 Jan 1529 Richard Stanhope died.

On 21 Jan 1541 Elizabeth Windsor (age 59) died.

On 21 Jan 1556 Eustace Chapuys (age 66) died.

On 21 Jan 1558 John Cope (age 54) died. John Dryden of Canons Ashby (age 33) and Elizabeth Cope (age 29) inherited Canons Ashby House.

On 21 Jan 1565 Margaret Mundy (age 55) died. She was buried the next day in Streatham, Surrey.

On 21 Jan 1567 Anne Heveningham (age 54) died.

On 21 Jan 1582 Elizabeth Cavendish Countess Lennox (age 26) died.

On 21 Jan 1590 Agnes Drummond Countess Eglinton (age 67) died.

On 21 Jan 1600 Marmaduke Tyrwhitt died.

On 21 Jan 1609 Joseph Justus Scaliger (age 68) died.

On 21 Jan 1623 Magdalena Smith (age 79) died.

On 21 Jan 1645 Susan Rowe Countess Warwick (age 63) died.

On 21 Jan 1653 John Digby 1st Earl Bristol (age 72) died in Paris [Map]. His son George Digby 2nd Earl Bristol (age 40) succeeded 2nd Earl Bristol. Anne Russell Countess Bristol (age 33) by marriage Countess Bristol.

On 21 Jan 1653 Lawrence Washington (age 51) died.

On 21 Jan 1661 William Booth (age 12) died.

On 21 Jan 1664 Colonel James Turner (age 55) was hanged at St Mary Axe.

Around 21 Jan 1668 Anthony Joyce committed suicide by jumping into a pond in Islington [Map]. On 24 Jan 1668 he was buried at St Sepulchre without Newgate Church.

On 21 Jan 1674 Henri Tremoille (age 75) died.

On 21 Jan 1683 Anthony Ashley-Cooper 1st Earl Shaftesbury (age 61) died. His son Anthony Ashley-Cooper 2nd Earl Shaftesbury (age 31) succeeded 2nd Earl Shaftesbury, 2nd Baron Ashley of Wimborne St Giles, 3rd Baronet Cooper of Rockbourne in Southampton. Dorothy Manners Countess Shaftesbury (age 27) by marriage Countess Shaftesbury.

On 21 Jan 1683 Elizabeth Garrard Lady Gould (age 39) died.

On 22 Oct 1691 Lucius Knightley (age 68) died in Fawsley, Northamptonshire. On 21 Jan 1710 Elizabeth Dent (age 77) died. They were buried in St Mary's Church, Fawsley [Map].

Lucius Knightley: On 03 Apr 1623 he was born to Richard Knightley in Fawsley, Northamptonshire. Before 22 Oct 1691 Lucius Knightley and Elizabeth Dent were married.

Elizabeth Dent: On 02 Nov 1632 she was born.

On 21 Jan 1695 Margaret Hamilton of Preston (age 70) died.

On 21 Jan 1699 Obadiah Walker (age 83) died.

On 21 Jan 1700 Henry Somerset 1st Duke Beaufort (age 71) died at Badminton, Gloucestershire. He was buried at Beaufort Chapel, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle [Map]. His grandson Henry Somerset 2nd Duke Beaufort (age 15) succeeded 2nd Duke Beaufort, 4th Marquess Worcester, 8th Earl Worcester.

On 21 Jan 1702 James Annesley 3rd Earl Anglesey (age 27) died. His brother John Annesley 4th Earl Anglesey (age 26) succeeded 4th Earl Anglesey, 5th Viscount Valentia, 4th Baron Annesley Newport Pagnell Buckinghamshire.

On 21 Jan 1704 Louis François Bourbon Condé Conti died.

On 21 Jan 1709 Nathaniel Napier 2nd Baronet (age 73) died. His son Nathaniel Napier 3rd Baronet (age 41) succeeded 3rd Baronet Napier of Middle Marsh in Dorset. Catherine Alington Lady Napier (age 24) by marriage Lady Napier of Middle Marsh in Dorset.

On 21 Jan 1710 John Ashburnham 1st Baron Ashburnham (age 54) died at Southampton Street. His son William Ashburnham 2nd Baron Ashburnham (age 30) succeeded 2nd Baron Ashburnham of Ashburnham in Sussex. Catherine Taylor by marriage Baroness Ashburnham of Ashburnham in Sussex.

On 21 Jan 1722 Charles Paulet 2nd Duke Bolton (age 61) died. His son Charles Powlett 3rd Duke Bolton (age 36) succeeded 3rd Duke Bolton, 8th Marquess Winchester, 8th Earl Wiltshire, 8th Baron St John. Anne Vaughan Duchess Bolton by marriage Duchess Bolton.

On 21 Jan 1757 Frederick Augustus Perceval (age 7) died.

On 21 Jan 1765 Hugh Willoughby 15th Baron Willoughby of Parham died unmarried. His fourth cousin Henry Willoughby 16th Baron (age 69) succeeded 16th Baron Willoughby Parham. He had a better claim to the title than the 15th Baron being descended from the second son but no action was taken until the death of the 15th Baron when he succeeded to the title. By law the 11th to 15th Barons should be considered a new creation.

On 21 Jan 1768 Samuel Fludyer (age 63) died.

On 21 Jan 1773 Charlotte Finch Duchess Somerset (age 80) died.

On 21 Jan 1775 John Browne 5th Baronet died. Baronet Browne of Caversham extinct.

On 21 Jan 1779 Elizabeth Noel died.

On 21 Jan 1783 Mary Chambers Baroness Spencer (age 69) died.

On 21 Jan 1783 George Armytage 3rd Baronet (age 48) died.

On 21 Jan 1793 Louis XVI King France (age 38) was guillotined in Paris [Map]. His son Louis XVII King France (age 7) de jure XVII King France: Capet Valois Bourbon.

On 21 Jan 1805 George Austen (age 74) died.

On 21 Jan 1811 Elizabeth Harcourt Lady Lee (age 71) died.

Before 21 Jan 1814 Colonel Joseph Sabine (age 70) died. He was buried on 21 Jan 1814 at St Michael the Archangel Church, Teignmouth.

On 21 Jan 1814 Maria Hamilton (age 28) died.

On 21 Jan 1822 Buckworth Buckworth-Herne-Soame 6th Baronet (age 59) died. His son Peter Buckworth-Herne-Soame 7th Baronet (age 28) succeeded 7th Baronet Buckworth-Herne-Soame of Sheen in Surrey.

On 21 Jan 1832 Louisa Elizabeth Gage (age 66) died.

On 21 Jan 1845 Walter Aston 9th Baronet (age 75) died. Baronet Aston of Tixall extinct.

On 21 Jan 1845 Samuel Colman (age 65) died.

On 21 Jan 1846 Duke Francis IV of Modena (age 66) died.

On 21 Jan 1850 Edward Vansittart Neale (age 81) died.

On 21 Jan 1850 Susanna Edith Harland (age 87) died.

On 21 Jan 1858 Emily Anne Bennet Elizabeth Cecil Marchioness Westmeath (age 68) died.

On 21 Jan 1861 Walter Sewallis Shirley (age 1) died.

On 21 Jan 1867 Robert King 4th Earl Kingston (age 70) died unmarried. His brother James King 5th Earl Kingston (age 66) succeeded 5th Earl Kingston.

On 21 Jan 1876 Isabella Williamson (age 42), and her two sons James Charles Allgood (age 13) and David Williamson Allgood (age 11) died in a railway accident at Abbots Ripton.

On 21 Jan 1876 Herbert Noble (age 19) died in a railway accident at Abbots Ripton. The Special Scotch Express train from Edinburgh to London was involved in a collision, during a blizzard, with a coal train. An express travelling in the other direction then ran into the wreckage.

On 21 Jan 1883 Anna Eliza Kempe (age 92) died.

On 21 Jan 1883 Charles Hohenzollern (age 81) died.

On 21 Jan 1884 Louisa Chaplin died.

On 21 Jan 1887 Henry Edwyn Chandos Scudamore Stanhope 9th Earl of Chesterfield (age 65) died at Victoria Hotel. His son Edwyn Scudamore Stanhope 10th Earl of Chesterfield (age 32) succeeded 10th Earl Chesterfield, 10th Baron Stanhope of Shelford in Nottinghamshire, 4th Baronet Stanhope of Stanwell.

On 21 Jan 1889 George Henry Cavendish (age 65) died.

On 21 Jan 1894 Emma Barnett died one week after the death of her husband William John Butler (deceased).

On 21 Jan 1900 Francis Teck (age 62) died. His son Adolphus Cambridge Duke Teck (age 31) succeeded Duke Teck. Margaret Evelyn Grosvenor Duchess Teck (age 26) by marriage Duchess Teck.

On 21 Jan 1902 Caroline Pepys died.

On 21 Jan 1903 Kenneth Howard (age 57) died.

On 21 Jan 1923 Major-General Hugh Richard Dawnay 8th Viscount Downe (age 78) died. succeeded 9th Viscount Downe.

On 21 Jan 1928 Captain Justinian Edwards-Heathcote of Apedale Hall in Staffordshire (age 85) died.

On 21 Jan 1928 Henry Frederick Compton Cavendish (age 73) died.

On 21 Jan 1931 Cecil Charles Cavendish (age 75) died.

On 21 Jan 1934 Friedrich Ferdinand Glücksburg Duke Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg (age 78) died. His son Wilhelm Friedrich Christian Glücksburg Duke Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg (age 42) succeeded Duke Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg. Marie Melita Hohenlohe Langenburg Duchess Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg (age 35) by marriage Duchess Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg.

On 21 Jan 1937 Evelyn Georgiana Cust (age 79) died.

On 21 Jan 1951 Geoffrey Cornewall 6th Baronet (age 81) died. His brother William Francis Cornewall 7th Baronet (age 79) succeeded 7th Baronet Amyand aka Cornewall of Moccas Court in Herefordshire.

On 21 Jan 1958 Alexandra Louise Elizabeth Acheson (age 80) died.

On 21 Jan 1967 Dorothea Maria Saxe Coburg Gotha Duchess Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Augustenburg (age 85) died.

On 21 Jan 1970 Constance Edwina "Shelagh" Cornwallis-West Duchess Westminster (age 94) died.

On 21 Jan 1972 Oliver Lyttelton 1st Viscount Chandos (age 78) died.

On 21 Jan 1976 Marie Henrietta Keppel Countess of Romney (age 85) died.

On 21 Jan 1978 Edward Robert Blount 11th Baronet (age 93) died. His son Walter Edward Alpin Blount 12th Baronet (age 60) succeeded 12th Baronet Blount of Sodington.

On 21 Jan 1991 Ileana Hohenzollern Sigmaringen Archduchess Austria (age 82) died at Youngstown Ohio.