On this Day in History ... 6th June

06 Jun is in June.

1348 Black Death Plague Outbreak

1474 Anne Beauchamp declared Legally Dead

1535 Execution of Bishop Fisher and Thomas More

1559 Creation of Garter Knights

Events on the 6th June

On 06 Jun 1097 Agnes Poitiers Queen Consort Aragon Queen Consort Pamplona (age 25) died.

On 06 Jun 1217 Henry I King Castile (age 13) Was killed by a tile falling of a roof. He was buried at Abbey of Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas. His sister Berengaria Ivrea I Queen Castile (age 38) succeeded I Queen Castile.

On 06 Jun 1349 William Harcourt (age 49) died of plague at Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire [Map].

On 06 Jun 1441 William Phelip (age 58) died. He was buried at St Mary's Church, Dennington [Map]. Monument to William Phelip (age 58) and Joan Bardolf (age 50). Early Plate Bascinet and Gorget Period. Feathered Crest. Detail of the Wyvern on which her feet rest. Detail of Eagle, possibly hawk, on which his feet rest. Crespine Headress covering her hair. He wearing a bascinet with IHC NASARE Lettering. Both wearing a Lancastrian Esses Collar. Leg Garter below the left knee.

Calendars. 06 Jun 1474. Westminster Palace [Map]. Exemplification at the request of Richard Duke of Gloucester (age 21), of the tenour of an act (English) in the Parliament summoned at Westminster [Map], 6 October, 12 Edward IV, and continued to 9 May, 14 Edward IV, ordaining that George Duke Clarence (age 24), and Isabel (age 22) his wife and Richard Duke of Gloucester, and Anne (age 17) his wife, daughters and heirs to Richard Nevyle, late Earl of Warwick, and daughters and heirs apparent to Anne Beauchamp (age 47), his wife should possess and enjoy as in the right of the said wives all possessions belonging to the said Countess as though she were naturally dead and that she should be barred and excluded therefrom, that they should make partition of the premises and the same partition should be good in law, that the said Dukes should enjoy for life all the possessions of their wives if they should outlive the latter, that the said George (age 24) and Isabel (age 22) should not make any alienation, grant, fine or recovery of any of the premises to the hurt of the said Richard (age 21) and Anne (age 17) or the latter to the hurt of the former, that if the said Richard and Anne be divorced and afterwards married this Act should hold good, that if they be divorced and he do his effectual diligence to be married to her and during her life be not wedded to any other woman he should enjoy as much of the premises as should appertain to her during his life, and that notwithstanding the restraint of alienation or recovery above specified the lordship, manor and wappentake of Chesterfield [Map] and Scarvesdale with the appurtenances and all the lands and tenements in Chesterfield [Map] and Scarvesdale sometime of Ales, late Countess of Salisbury, might be given to the King and his heirs in exchange for other lands and tenements, which shall however be subject of this Act.Anne Beauchamp declared Legally Dead.

Letters and Papers 1535. 06 Jun 1535. Add. MS. 8715. f. 67 b. B. M. 837. Bishop of Faenza to M. Ambrogio.

* * * Spoke at length to the French king of the Pope's concern about Fisher (Rossense instead of Roffense), and begged him to use his influence with the king of England for his liberation, for he ought to be able to obtain a greater thing than that from him. He replied that there was no need to speak of his virtues, which were known to all the world, both by his books, for no one had written better than he against the Lutherans, and by his innumerable virtues. His Holiness might be sure he would do what he could for his liberation; but he doubted his success, for he feared this hat would cause him much injury, according to what he heard from England, where they have been using strange methods against the Carthusians. He added that the king of England was the hardest friend to bear in the world; at one time unstable, and at another time obstinate and proud, so that it was almost impossible to bear with him. "Sometimes," said Francis, "he almost treats me like a subject, e vero dico che come mi rolte anch' in egli caglia: in effect, he is the strangest man in the world, and I fear I can do no good with him, but I must put up with him, as it is no time to lose friends" He would, however, do what he could for Fisher's (Rossetto) liberation. Offered to give the King the brief and hat for Fisher, and that all should be put in the Grand Master's hands, so that it might be done sooner according to the Pope's William He told the Bishop to keep them, and he would be asked for them when it was time. The card. du Bellay (il Rmo. Bellier) has also promised to do what he can, but he fears this Cardinalate will make Fisher a martyr. They will try to find some means to make the king of England take it as he ought.

Will lose no time, and do all he can for his liberation. Would rather see Fisher in Rome than be a cardinal himself, for he hears on every side that his virtue is not less than what the world wants now, "ne sua Beatitudine potra fare in queste bande cosa piu degna di lei."

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. R. O. 1075. John Husee to Lady Lisle (age 42).

I have your three sundry letters. I can hear nothing of the liveries you sent to John Davy. I think one of Mr. Marshall's servants has the conveyance of them, but Mr. Degory's livery I have delivered to Mr. Chichester. I am glad the gentlewoman has arrived. The bowls, I assure you, cost no farthing less, and if you like them not the poor man that made them will take them back. Mine host hopes you will appoint him some venison; but one thing you may be sure of, "that my hostess is the honest man." As for Antony Husee's wife's cushion, I shall do as your Ladyship shall command me. I am much bound for the pains you have taken about my check. When I deliver my Lord's letter to Mr. Hennage I will move the preferment of your daughter to the Queen, which I hope will be easily obtained. It might be well to send lord Dawbny a piece of wine, but Mr. Sulyard must not be forgotten. The Queen's (age 27) brother (age 36) was this day created Viscount Beauchamp. Mr. Tayler sends commendations. It was reported here that Mr. Rockwood was dead. Your gown shall be made with all speed. London, 6 June.

Cranewell, Harwod, and Myller desire you to remember their liveries.

Hol., pp. 2. Add.

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. R. O. 1074. J. Husee to Lord Lisle (age 72).

I have received your letters of the 2nd and 3rd June. In answer to the first, touching Sir Richard Whethill, Mr. Prysley this night delivered him your letter, and declared your pleasure, to which he only hummed and hawed, but at last said he had made many friends; so that apparently he means to persevere in his malicious suit. Mr. Prisley, however, still hopes he will take further advisement. The negligence about your Lordship's hosen was owing to my bedfellow Fyssher, who would not suffer me to send them by any other than himself. He deserves to sit three days in the stocks for it, but it rests with your Lordship to qualify the punishment. As for the parson of St. Martin's, I stayed 40s. in my hands for the tenth, before your Lordship's letter came to hand. As to your other letter I shall deliver Mr. Hennage your Lordship's letter, and motion him of my lady's daughter. As to the nomination of an abbey, I wrote by Petley, and will make further search. When I have set these matters in frame I will follow your affairs in Hampshire. The proxy I shall deliver the second day of the Parliament, as the custom is. Snowden is a diligent waiter, but Mr. Treasurer (age 46) has not yet motioned the King in his cause. I hope he will be earnest when he begins. As for the Marsh, though the matter has been taken by Water's information not after the true meaning, Mr. Secretary says the letter I send with this is wholly the King's pleasure, and will satisfy you. Wriothesley had this letter five days, and never told me till today at Court, but delivered it to me this night at Stepney. Mr. Secretary was not a little displeased at this, but in truth Wriothesley favored the party, or he would not have kept it. If you send lord Dawbny a piece of wine it would do no harm. As to my check, your Lordship's letter to Mr. Treasurer (age 46) will ease it. I will certify Mrs. Medcalff of your pleasure touching Lyssle: You will receive a letter of the King's for Peretrey's pardon along with this other letter of the King's sent herewith. Remember Mr. Secretary's wine. I cannot yet know what answer the King made him touching your suit. The Queen's (age 27) brother (age 36) is today created Viscount Beauchamp. London, 6 June.

Hol., pp. 2. Add. Endd.

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. On Whitsun eve, in the morning, Cromwell came to see me at my lodging, although I had sent to request him to wait for me at his own, and first told me, pour joyeuse entrée, that the King and the new Queen (age 27) were wonderfully well pleased with the wise and prudent letters the Princess (age 20) had written (in which, nevertheless, there was nothing corresponding to the draft abovementioned, nor anything that could prejudice her), and that the King was resolved to make her his heir, which he supposed to be one of the principal articles of my charge on which the rest depended. Now, it is true that I had perceived some indications that there was a proposal to declare the Princess (age 20) heir without giving her the title of Princess, and she will remain excluded in case of a son or daughter being born. If this be so, and I see an opportunity to remedy it, I will speak about the subject. If not, I will not stick at it much, hoping that by the establishment of peace and augmentation of amity, with the great prudence and virtue the King will perceive in her, that she will be declared true and just princess,—although, according to the opinion of many, there is no fear of the occurrence of any issue of either sex. Coming to the principal subject, Cromwell said that he had repeated to the King his master the communications we had had together, and the King had given him patient audience, well noting and considering everything, and that he had since heard the French ambassadors, to whom he had made a brusque reply, first as to the marriage of the Dauphin with the Princess, that he knew not why they urged it, as at the meeting at Calais he had resolutely replied about it to the king of France, his brother, and as to the duke of Angoulême he was too young for the said Princess, who was of marriageable age. As to declaring himself against your Majesty, he saw no ground for it, and though they said that your Majesty had been and was his enemy, he did not see it; he had much greater occasion to complain of several who had called themselves his friends, and he could very well testify what they had done about the "privation" and other things; and as to the danger which they alleged to him, which was the sole motive they made use of, that your Majesty aspired to universal monarchy, and that you were revengeful of injuries—that the English, after feasting France, would have their St. Martin—there was not the slightest fear, for they knew the nature of your Majesty, and for other good reasons besides. As to assisting them with a contribution for the war, he also declined it for the same reason. As to the suggestion that he should take this affair in hand in order to bring to agreement your Majesty and the King their master, and that he would write to your Majesty to procure an abstinence of war while they were treating of peace, he replied that it was not reasonable that he should write such letters, for several reasons, especially as the amity between your Majesty and him was not well consolidated, but he would request me to write with diligence to your Majesty to consent, notwithstanding past matters, to an honorable peace, and used such arguments with me as he thought fit. But, considering everything, he had very little occasion to meddle with such matters, seeing that they had turned about on all sides in their negociations, even to his disadvantage, employing therein his principal enemy, the Pope, and without informing him of anything important, except at the end when the matter came to be broken off. For a compliment, they had asked him how he would be comprehended in the peace, in which matter your Majesty had acted more honorably and cordially, having told him by me that it was in his power to be the principal contrahent, and to comprehend those whom he pleased. At which words Cromwell said the King showed great delight, saying further, that the French, after so much trifling and making a thousand offers, which he repeated to the ambassadors, especially those that the cardinal of Lorraine had made to your Majesty, and seeing themselves deserted by everybody and in great danger of being completely baffled, now came to him and tried to make him stumble with them in the ditch into which they had blindly precipitated themselves, and that it was no wonder their affairs went so badly, considering the envy and dissension between the Grand Master and the Admiral, who were chief of the Council, and that they need not have made so much boast hitherto to lower their ears immediately after, and that your Majesty managed your affairs more honorably without so much fuss, and yet showed clearly that you were not in such need and poverty as the French had pretended. And here the King inveighed strongly against the cruel enterprise of the French against the duke of Savoy. Such was, as Cromwell affirmed, the King's reply to the French ambassadors, which he ended by telling them that if their master wished him to promote this peace, they must put aside passion and cupidity and submit to reason; which, in his opinion, suggested that a king of France should be satisfied with such a wealthy kingdom, without irritating the flies by which he might be provoked. And he desired that the ambassadors should write with diligence to learn the will of the King their master upon this matter, and have it set forth in articles.

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. Vienna Archives. 1070. Chapuys (age 46) to [Granvelle].

The night before Anne (deceased) was beheaded she talked and jested, saying, among other things, that those bragging, clever persons who had invented an unheard-of name for the good Queen would not find it hard to invent one for her, for they would call her "la Royne Anne sans teste;" and then she laughed heartily, though she knew she must die the next day. She said, the day before she was executed, and when they came to lead her to the scaffold, that she did not consider that she was condemned by Divine judgment, except for having been the cause of the ill-treatment of the Princess, and for having conspired her death.

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. On his return from mass I accompanied the King to the chamber of the Queen (age 27), whom, for the King's satisfaction, I kissed, and congratulated her on her marriage, and said that her predecessor had borne the device La plus heureuse, but that she would bear the reality, and that I was sure your Majesty would be immeasurably pleased that the King had found so good and virtuous a wife, especially as her brother had been in your Majesty's service, and the satisfaction of this people with the marriage was incredible, especially at the restoration of the Princess to the King's favor and to her former condition; and, among other congratulations, I told the Queen (age 27) that it was not her least happiness that, without having had the labour of giving birth to her, she had such a daughter as the Princess, of whom she would receive more joy and consolation than of all those she could have herself; and I begged her to favor her interests; which she said she would do, and especially that she would labour to obtain that honorable name I wished for her of "pacific," i.e., of author and conservatrix of the peace. After speaking to the Queen (age 27), the King, who had been talking to the other ladies, approached, and wished to excuse her, saying I was the first ambassador to whom she had spoken, and she was not accustomed to it, that he quite believed she desired to obtain the name of "pacific," for, besides that her nature was gentle and inclined to peace, she would not for the world that he were engaged in war, that she might not be separated from him. After dinner I went to speak with the King in his chamber, and protesting "pour non lui altérer son cerveaul," [so as not to alter his brain] that I would not for the present object to the answers made by Cromwell, I begged him to take in good part that which I should say about the conversations Cromwell and I had had together. He desired that I would speak boldly. And I began to make part of the remonstrances I had made to Cromwell. He replied that it was true that the leagues and confederacies between your Majesty and him are far more ancient and better grounded than those with France; and, that notwithstanding it was true that the cause for which they had been made with France had ceased, he could not on that account fail in the promise he had made, for he was bound to both parties to defend the party attacked, and the French pretended that they were entitled to do what they had done against the duke of Savoy, because he had refused to restore Nice, which was only a surety, without violating the peace, and it was quite another thing to invade one of those comprehended in the peace from what it was to invade the subjects and dominions of a principal con trahent. And he begged your Majesty would look to this, lest by attacking France you might be called the aggressor, and he should be compelled by treaty to defend the party attacked, which would be disagreeable for him. On my showing him the articles in which the French had infringed the peace, he replied, as to Gueldres he was not informed, but he knew that a French gentleman who had been conveying money to Gueldres on the part of Francis had been taken at Brussels, and he did not think your Majesty would pretend a rupture on that account, seeing that you had made no mention of it in your statement at Rome. As to Wirtemberg, he tried to excuse the French, saying the Duke had gone to seek them, and the money the French had delivered was for the purchase of certain lands, and that the Duke was only subject to your Majesty much in the same way as the duke of Savoy. He attaches more importance to what the French have done "en lendroit de loccupateur de Mirandula;" but in the end he gave up almost every point, although he wished somehow to excuse an incursion lately made by the French on the frontiers of Artois, saying it was done by peasants of their own accord. After much talk the King notified to me that it would be necessary, in order to soften both parties, to tell them their wrong and show some "braverie," begging your Majesty to consider the good that would come of a new peace; and instead of commanding, he begged me to do my duty in this matter, not once but at least ten times, saying to me "Monsieur, je vous supplie, considerez, faictez, ecrivez, &c.," [Sir, I beg you, consider, do, write] which was quite extravagant courtesy. At last, seeing that it was no use pressing him to declare himself, I asked him what, in conclusion, I was to write to your Majesty. He replied that I ought to know better than he; but since I asked him he thought I should write that if you were willing that he should mediate this peace he would do it willingly, and would take care to allow no article that was not honorable to your Majesty. I said he ought to bid me write another article, viz., that in case he found the French to be violators of the peace or aggressors, or that they would not agree to a reasonable peace, he should declare himself for your Majesty. He replied cheerfully and distinctly that I might boldly assure your Majesty of it. He did not repeat what he had said before, that it was necessary also that he should use such "braverie" towards your Majesty in case you were wrong, nor that it must be considered if new conditions more unreasonable than the previous were put forward he should consider himself mocked by the parties unless it was owing to expenses since incurred, or a change in the situation. The King having explained to me as above I told him he might hold it certain that he would find all the fault was on the side of the French, as he would see clearly if he would weigh a little what I had said to him. Moreover, the French would never consent to honorable conditions. I therefore begged him to consider from this time about making a new treaty with your Majesty, and that he would declare to me what he would demand on his part in like case. He said to me he had certainly not considered about it, and for the haste of this despatch, as he had not all his council, he could not at present determine, but I might write to your Majesty that I would inform you of everything by the first despatch.

Letters 1536. 06 Jun 1536. Vienna Archives. 1069. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

On the 24th of this month, the Eve of Ascension Day, immediately on the arrival of the courier who was despatched to Pontremolo, Cromwell sent me the packet which your Majesty had forwarded to that place, begging that I would impart my news to him without delay. Shortly afterwards he sent to say that he would come and see me, but as, owing to his being so much occupied, he had failed in a like promise two days before, I, in order to put him under greater obligation, went to see him. On my arrival he told me that he had been to Court that morning, only to obtain audience for me, which the King had granted for next day. The said courier had brought letters from their ambassador, giving such news of the sincere goodwill your Majesty bore the King that Cromwell said he was better pleased than if he had gained 100,000 cr.; and he was sure I should find the King otherwise inclined than he had been before, both as regards the principal matter and also as to myself in particular, for I had greatly increased the affection he bore me on account of certain letters I had lately written to him, of which I send a copy to Grandvelle; also that by the death of the Concubine (deceased) matters would be more easily arranged now than they had been. He said it was he who had discovered and followed up the affair of the Concubine (deceased), in which he had taken a great deal of trouble, and that, owing to the displeasure and anger he had incurred upon the reply given to me by the King on the third day of Easter, he had set himself to arrange the plot (a fantasier et conspirer led. affaire), and one of the things which had roused his suspicion and made him enquire into the matter was a prognostic made in Flanders threatening the King with a conspiracy of those who were nearest his person. On this he praised greatly the sense, wit, and courage of the said Concubine (deceased) and of her brother (deceased). And to declare to me further the hope of good success, he informed me in great confidence that the King, his master, knowing the desire and affection of all his people, had determined in this coming Parliament to declare the Princess (age 20) his heir; but by what he said afterwards, which I shall partly report, he left me in much greater doubt than before. For, besides requesting me in speaking to the King not to make any request on the Princess's behalf, and, if she were mentioned, not to speak of her as Princess, he also told me it was above all things necessary the Princess should write a letter to her father according to a draft that Cromwell had drawn up in the most honorable and reasonable form that could be, and that to solicit the Princess to do this he had, by the King's command, sent to her a very confidential lady; but, in any case, to avoid scruple, the King wished I would write to her, and send her one of my principal servants to persuade her to make no difficulty about writing the said letter, which he would have translated from English into Latin, that I might see that it was quite honorable. This translation he gave me next day as I left the Court; and since reading it I have not found the said Cromwell, to tell him my opinion of it, although I begged him the day before, when he spoke about it, to take care that it did not contain anything which could directly or indirectly touch her right, or the honor either of herself or of the late Queen, her mother, nor yet her conscience; otherwise she would not consent thereto for all the gold in the world, and the King's indignation against her would only be increased; and that he whom the said Princess regarded as almost a father, ought to take good care that the whole was free from danger and scruple. This, he said, he had done, as I should see by the tenor of the letter, of which I send your Majesty the very translation he delivered to me. Besides the evidence that letter contains that there is some bird catching attempted (quy y a de la traynee et pipe), this has been confirmed to me from a good quarter, and I have warned the Princess. I mean to get out of it (de me demesler) and dissemble the affair as much as I can, without speaking or writing of it till I have understood the intention of those here on the principal article of the negotiations. I shall excuse myself for not having sent to the Princess by saying that the messenger (icelluy) to whom I had committed the translation had lost it in returning from Court. When I have learned their intention I shall not fail to make the necessary remonstrances as to the unreasonableness of the letter, and seek all means possible to moderate such rigour; nevertheless your Majesty will be pleased to instruct me what to say and do in case the King insist on having the letter entirely written by the Princess, and that otherwise he means to punish her, as the lady sent by the King to the Princess has given a servant of mine to understand.

Henry Machyn's Diary. 06 Jun 1559. [The vj day of June saint George's feast was kept at Windsor [Map];] the yerle of Pembroke (age 58) was the [Queen's substitute,] lord Montycutt (age 30) and my lord of ....; ther was stallyd at that tyme the duke of [Norfolk] (age 23), my lord marques of Northamtun (age 47), and the yerle of [Rutland] (age 32), and my lord Robart Dudley (age 26) the master of the quen('s) horse, nuw mad knyghtes of the Garter, and ther was gret [feasting] ther, and ther be-gane the comunion that day and Englys.

On or before 06 Jun 1599 Diego Velázquez was born. He was baptised on 06 Jun 1599.

On 06 Jun 1646 Hortense Mancini Duchess of Mazarin was born to Lorenzo Mancini (age 44).

On 06 Jun 1655 Geoffrey Palmer 1st Baronet (age 57) was imprisoned in the Tower of London [Map] on suspicion of raising forces against Oliver Cromwell (age 56)..

In Jun 1660 King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland (age 30) rewarded those who supported his Restoration ...

6th William Wray 1st Baronet (age 35) and John Talbot of Lacock (age 29) were knighted.

7th Geoffrey Palmer 1st Baronet (age 62) was created 1st Baronet Palmer of Carlton in Northampton

7th Orlando Bridgeman 1st Baronet (age 54) was created 1st Baronet Bridgeman of Great Lever in Lancashire.

7th John Langham 1st Baronet (age 76) was created 1st Baronet Langham of Cottesbrooke in Northamptonshire.

11th Henry Wright 1st Baronet (age 23) was created 1st Baronet Wright of Dagenham. Ann Crew Lady Wright by marriage Lady Wright of Dagenham.

13th Nicholas Gould 1st Baronet was created 1st Baronet Gould of the City of London.

14th Thomas Allen 1st Baronet (age 27) was created 1st Baronet Allen of Totteridge in Middlesex.

18th Thomas Cullum 1st Baronet (age 73) was created 1st Baronet Cullum of Hastede in Suffolk.

19th Thomas Darcy 1st Baronet (age 28) was created 1st Baronet Darcy of St Osith's.

22nd Robert Cordell 1st Baronet was created 1st Baronet Cordell of Long Melford.

22nd John Robinson 1st Baronet (age 45) was created 1st Baronet Robinson of London. Anne Whitmore Lady Robinson (age 48) by marriage Lady Robinson of London.

25th William Bowyer 1st Baronet (age 47) was created 1st Baronet Bowyer of Denham Court. Margaret Weld Lady Bowyer (age 43) by marriage Lady Bowyer of Denham Court.

25th Thomas Stanley 1st Baronet (age 63) was created 1st Baronet Stanley of Alderley in Cheshire.

26th Jacob Astley 1st Baronet (age 21) was created 1st Baronet Astley of Hill Morton.

27th William Wray 1st Baronet (age 35) was created 1st Baronet Wray of Ashby in Lincolnshire. Olympia Tufton Lady Ashby (age 36) by marriage Lady Wray of Ashby in Lincolnshire.

28th Oliver St John 1st Baronet (age 36) was created 1st Baronet St John of Woodford in Northamptonshire.

29th Ralph Delaval 1st Baronet (age 37) was created 1st Baronet Delaval of Seaton in Northumberland. Anne Leslie Lady Delaval by marriage Lady Delaval of Seaton in Northumberland.

30th Andrew Henley 1st Baronet (age 38) was created 1st Baronet Henley of Henley in Somerset.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Jun 1665. Waked in the morning before 4 o'clock with great pain to piss, and great pain in pissing by having, I think, drank too great a draught of cold drink before going to bed. But by and by to sleep again, and then rose and to the office, where very busy all the morning, and at noon to dinner with Sir G. Carteret (age 55) to his house with all our Board, where a good pasty and brave discourse. But our great fear was some fresh news of the fleete, but not from the fleete, all being said to be well and beaten the Dutch, but I do not give much belief to it, and indeed the news come from Sir W. Batten (age 64) at Harwich [Map], and writ so simply that we all made good mirth of it.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Jun 1666. Then home and found my wife at dinner, not knowing of my being at church, and after dinner my father and she out to Hales's (age 66), where my father is to begin to sit to-day for his picture, which I have a desire to have. I all the afternoon at home doing some business, drawing up my vowes for the rest of the yeare to Christmas; but, Lord! to see in what a condition of happiness I am, if I would but keepe myself so; but my love of pleasure is such, that my very soul is angry with itself for my vanity in so doing.

Pepy's Diary. 06 Jun 1666. Anon took coach and to Hales's (age 66), but he was gone out, and my father and wife gone. So I to Lovett's, and there to my trouble saw plainly that my project of varnished books will not take, it not keeping colour, not being able to take polishing upon a single paper.

The London Gazette 684. Rochester, 06 Jun 1672.

Yesterday was performed the solemn Enterment Monseur Rabiniere tres le boys, Rear-Admiral of the French Squadron who some days since dyed here of the Wounds he received in the late Engagement. The Corps was accomapanied by several persons of quality (his Pall being born up by Sir Johnathan Atkins (age 62), His Majesties Governor here, Colonel Rheyms (age 58), Mr Evelin (age 51), and a person of quality related to the Deceased) together with the Mayor and Alderman of this place in the Formalities, and all other solemnity we are here capable of, to the place of Enterment, which was in the Quire of our Cathedral Church [Map], where was pronounced an excellent Funeral Oration with an Elogy on the Deceased by Dr. God, one of the Prebends; the whole having been concluded by three Volleys of the several Companies of Guard, now here, who likewise assisted at this Solemnity in excellent order.

On 06 Jun 1714 Joseph I King Portugal was born to John V King Portugal (age 24).

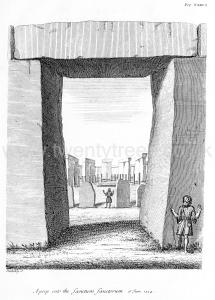

Stonehenge by William Stukeley. Table VII. A Peep into the Santum Sanctorum [Map].

On 03 May 1795 Richard James Wyatt was born to Edward Wyatt (age 38) and Anne Maddox in Oxford Street, London. He was baptised on 06 Jun 1795.

After 06 Jun 1808. Memorial to Martha Venables-Vernon (deceased) at All Saints Church, Sudbury [Map].

Martha Venables-Vernon: On 25 Dec 1751 she was born to George Venables-Vernon 1st Baron Vernon and Martha Harcourt Baroness Vernon of Kinderton. On 06 Jun 1808 Martha Venables-Vernon died.

On 06 Jun 1856 Theresa Susey Helen Chetwynd-Talbot Marchioness Londonderry was born to Charles Chetwynd-Talbot 19th Earl of Shrewsbury 4th Earl Talbot (age 26) and Anna Theresa Cockerell Countess Shrewsbury and Waterford (age 20).

The Diary of George Price Boyce 1855-1857. 06 Jun 1857. Received from Wm. Rossetti (age 27) circular of the New York Exhibition of British Art. Works to be in readiness by end of August. Augustus Ruxton projector. F. M. Brown (age 36) goes with the things.

On 06 Jun 1857 King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway (age 28) and Queen Sophia of Sweden and Norway (age 20) were married. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King George II of Great Britain and Ireland.

On 06 Jun 1894 Violet Keppel was born to George Keppel (age 28) and Alice Frederica Edmonstone aka Keppel (age 26). Her family considered her father was Ernest William Beckett 2nd Baron Grimthorpe (age 37).

On 06 Jun 1928 Captain Ralph Frederick Vane (age 36) died. He has a memorial at St Mary's Church, Staindrop [Map].

Captain Ralph Frederick Vane: On 08 Jun 1891 he was born to Henry de Vere Vane 9th Baron Barnard and Catherine Sarah Cecil Baroness Barnard.

On 06 Jun 2006 Leslie Alcock (age 81) died.

Births on the 6th June

On 06 Jun 1556 Edward Zouche 11th Baron Zouche Harringworth was born to George Zouche 10th Baron Zouche Harringworth (age 30) and Margaret Welby.

On 06 Jun 1564 Thomas Strickland was born to Walter Strickland (age 48).

On or before 06 Jun 1599 Diego Velázquez was born. He was baptised on 06 Jun 1599.

On 06 Jun 1602 Alexander Elphinstone 6th Lord Elphinstone was born to James Elphinstone of Barnes (age 21).

On 06 Jun 1620 John Covert 1st Baronet was born to Walter Covert of Maidstone, Kent and Ann Covert.

On 06 Jun 1620 William Fairfax 3rd Viscount Fairfax was born to Thomas Fairfax 2nd Viscount Fairfax (age 21) and Alathea Howard Viscountess Fairfax.

On 06 Jun 1646 Hortense Mancini Duchess of Mazarin was born to Lorenzo Mancini (age 44).

On 06 Jun 1670 Anne Knightley was born to Essex Knightley and Sarah Foley (age 21).

On 06 Jun 1678 Louis Alexandre Count of Toulose was born illegitimately to Louis "Sun King" XIV King France (age 39) and Françoise Athénaïs Marquise Montespan (age 37).

On 06 Jun 1681 Edward Henry Lee was born to Edward Lee 1st Earl Lichfield (age 18) and Charlotte Fitzroy Countess Lichfield (age 16). He a grandson of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 06 Jun 1714 Joseph I King Portugal was born to John V King Portugal (age 24).

On 06 Jun 1732 Richard Hill 2nd Baronet was born to Rowland Hill 1st Baronet (age 26) and Jane Broughton.

On 06 Jun 1735 George Hastings was born to Henry Hastings (age 34) and Elizabeth Hudson (age 34).

On 06 Jun 1736 Mary Cornwallis was born to Charles Cornwallis 1st Earl Cornwallis (age 36) and Elizabeth Townshend Countess Cornwallis.

On 06 Jun 1738 Edward Southwell 20th Baron Clifford was born to Edward Southwell (age 33) and Katherine Watson (age 22).

On 06 Jun 1739 August Adolf Wettin was born to Johann Adolph Wettin Duke Saxe Weissenfels (age 53) and Fredericka Saxe Coburg Altenburg (age 23) at Weißenfels, Burgenlandkreis, Saxony-Anhalt. Coefficient of inbreeding 3.94%.

On 06 Jun 1739 William Wyndham was born to William Wyndham (age 42).

On 06 Jun 1768 Admiral Joseph Sydney Yorke was born to Charles Yorke (age 45) and Agneta Johnson (age 27) at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire.

On 06 Jun 1770 Lieutenant-General William Stapleton was born to Thomas Stapleton 5th Baronet (age 43) and Mary Fane Lady Stapleton (age 26).

On 06 Jun 1770 Charles Cholmondeley was born to Thomas Cholmondeley (age 43).

On 06 Jun 1770 Joseph Sabine was born to Colonel Joseph Sabine (age 26) and Sarah Hunt (age 22) at Tewin, Hertfordshire.

On 06 Jun 1776 William Joseph Stourton 18th Baron Stourton was born to Charles Philip Stourton 17th Baron Stourton (age 23).

On 06 Jun 1786 Nicholas Bacon was born to Edmund Bacon 9th and 8th Baronet (age 36) and Anne Proctor Lady Bacon (age 37).

On 03 May 1795 Richard James Wyatt was born to Edward Wyatt (age 38) and Anne Maddox in Oxford Street, London. He was baptised on 06 Jun 1795.

On 06 Jun 1796 Caroline Paget Duchess Richmond was born to Henry William Paget 1st Marquess Anglesey (age 28) and Caroline Elizabeth Villiers Duchess Argyll (age 21).

On 06 Jun 1807 Frederick Hervey-Bathurst 3rd Baronet was born to Frederick Anne Hervey-Bathurst 2nd Baronet (age 24).

On 06 Jun 1815 Lowry Balfour Cole was born to John Cole 2nd Earl Enniskillen (age 47) and Charlotte Paget Countess Enniskillen (age 33).

On 06 Jun 1823 Francis Horatio Fitzroy was born to William Fitzroy (age 41).

On 06 Jun 1837 John Henry Kennaway 3rd Baronet was born to John Kennaway 2nd Baronet (age 40) and Emily Frances Kingscote Lady Kennaway (age 31).

On 06 Jun 1856 Theresa Susey Helen Chetwynd-Talbot Marchioness Londonderry was born to Charles Chetwynd-Talbot 19th Earl of Shrewsbury 4th Earl Talbot (age 26) and Anna Theresa Cockerell Countess Shrewsbury and Waterford (age 20).

On 06 Jun 1856 John Dewar 1st Baron Forteviot was born.

On 06 Jun 1860 Herbert Lloyd Watkin Williams-Wynn 7th Baronet was born to Colonel Herbert Watkin Williams-Wynn (age 38) and Anna Lloyd (age 26).

On 06 Jun 1869 Richard Harold St Maur was born illegitimately to Edward Adolphus Ferdinand Seymour (age 33) and Rosina Elizabeth Swan Maid at Tangier.

On 06 Jun 1870 Walter Hore Ruthven 10th Lord Ruthven of Freeland was born.

On 06 Jun 1870 Denis Le Marchant 3rd Baronet was born to Henry Denis Le Marchant 2nd Baronet (age 31) and Sophia Strutt Lady Le Marchant (age 24).

On 06 Jun 1872 Alix aka Alexandra Hesse Darmstadt was born to Prince Louis Hesse Darmstadt IV Grand Duke (age 34) and Princess Alice Saxe Coburg Gotha (age 29). She a granddaughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.

On 06 Jun 1877 Francis Gerald Cradock-Hartopp was born to Edmund Charles Cradock-Hartopp (age 30).

On 06 Jun 1894 Violet Keppel was born to George Keppel (age 28) and Alice Frederica Edmonstone aka Keppel (age 26). Her family considered her father was Ernest William Beckett 2nd Baron Grimthorpe (age 37).

On 06 Jun 1896 Lionel George Archer Cust was born to Lionel Cust (age 37) and Sybil Lyttelton (age 23).

On 06 Jun 1902 Cecilia Monica Wilson was born to Charles Henry Wellesley Wilson 2nd Baron Nunburnholme (age 27) and Marjorie Cecilia Wynn Carington Baroness Willoughby of Parham (age 22).

On 06 Jun 1919 Peter Carrington 6th Baron Carrington was born to Rupert Carrington 5th Baron Carrington (age 27).

On 06 Jun 1923 Robert Ernest Williams 9th Baronet was born to Ernest Claude Williams (age 24).

On 06 Jun 1924 June Wendy Pelham was born to Sackville Pelham 5th Earl of Yarborough (age 35).

On 06 Jun 1950 James St Aubyn 5th Baron St Aubyn was born to Oliver Piers St Aubyn (age 29).

On 06 Jun 1961 George Mountbatten 4th Marquess Milford Haven was born to David Mountbatten 3rd Marquess Milford Haven (age 42) and Janet Bryce Marchioness Milford Haven. He a great x 3 grandson of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.

Marriages on the 6th June

After 06 Jun 1349 Ralph Ferrers (age 20) and Joan Grey (age 47) were married. The difference in their ages was 27 years; she, unusually, being older than him. They were third cousins. He a great x 2 grandson of King Edward "Longshanks" I of England.

On 06 Jun 1573 Edward Manners 3rd Earl of Rutland (age 23) and Isabel Holcroft Countess Rutland (age 23) were married. She by marriage Countess of Rutland, Baroness Ros Helmsley. He the son of Henry Manners 2nd Earl of Rutland and Margaret Neville Countess Rutland.

On 06 Jun 1608 Thomas Wotton 2nd Baron Wotton (age 21) and Mary Throckmorton (age 18) were married.

Before 06 Jun 1614 Henry Thimblethorpe and Jane Calthorpe (age 24) were married.

On 06 Jun 1614 Edward Peyton 2nd Baronet (age 34) and Jane Calthorpe (age 24) were married.

Before 06 Jun 1620 Walter Covert of Maidstone, Kent and Ann Covert were married.

On 06 Jun 1630 John Murray 1st Earl Atholl and Jean Campbell Countess Atholl were married. She by marriage Countess Atholl. He the son of William Murray 2nd Earl Tullibardine and Dorothea Stewart Countess Tullibardine. They were second cousin once removed.

Before 06 Jun 1642 Robert Digby 1st Baron Digby (age 43) and Elizabeth Altham were married.

After 06 Jun 1642 Robert Bernard 1st Baronet (age 41) and Elizabeth Altham were married.

On 06 Jun 1643 Admiral William Penn (age 22) and Margaret Jasper (age 19) were married.

Before 06 Jun 1668 Robert Sheffield of Kensington and Mary Fanshawe (age 32) were married. They were first cousins.

On 06 Jun 1682 Charles Somerset Marquess Worcester (age 21) and Rebecca Child Marchioness Worcester (age 16) were married. He the son of Henry Somerset 1st Duke Beaufort (age 53) and Mary Capell Duchess Beaufort (age 51).

On 06 Jun 1687 William Williams-Wynn 2nd Baronet (age 22) and Jane Thelwall were married.

On 06 Jun 1699 Charles Cornwallis 4th Baron Cornwallis (age 24) and Charlotte Butler Baroness Cornwallis (age 20) were married. She by marriage Baroness Cornwallis. She the daughter of Richard Butler 1st Earl Arran and Dorothy Ferrers Countess Arran (age 44).

On 06 Jun 1702 James Long 5th Baronet (age 20) and Henrietta Greville Lady Long (age 18) were married at St Martin in the Fields [Map]. She by marriage Lady Long of Westminster in London.

On 06 Jun 1732 Rowland Hill 1st Baronet (age 26) and Jane Broughton were married.

On 06 Jun 1777 Adam Duncan 1st Viscount Duncan (age 45) and Henrietta Dundas were married.

On 06 Jun 1781 Peter I Grand Duke of Oldenburg (age 26) and Duchess Frederica of Württemberg (age 15) were married. They were half fourth cousins. She a great x 2 granddaughter of King George I of Great Britain and Ireland.

On 06 Jun 1786 George Capell Coningsbury 5th Earl Essex (age 28) and Sarah Bazett Countess Essex (age 26) were married. He the son of William Anne Capell 4th Earl Essex (age 53) and Frances Hanbury Williams Countess Essex.

On 06 Jun 1786 John Cragg of Threekingham (age 25) and Ann Warren (age 19) were married.

On 06 Jun 1787 Thomas Broughton 6th Baronet (age 42) and Anne Windsor Lady Broughton (age 26) were married. She by marriage Lady Broughton of Broughton in Staffordshire. She the daughter of Other Lewis Windsor 4th Earl Plymouth and Catherine Archer Countess Plymouth (age 50).

On 06 Jun 1791 James Buller (age 25) and Ann Buller (age 21) were married. She the daughter of Bishop William Buller (age 56) and Anne Thomas (age 53). They were first cousin once removed.

On 06 Jun 1803 John Freeman-Mitford 1st Baron Redesdale (age 54) and Frances Perceval Baroness Redesdale were married. She by marriage Baroness Redesdale of Redesdale in Northumberland. She the daughter of John Perceval 2nd Earl Egmont and Catherine Compton Countess Egmont.

On 06 Jun 1808 Robert Menzies of that Ilk 6th Baronet (age 27) and Emilia Balfour were married.

On 06 Jun 1854 Arthur Purey Cust (age 26) and Emma Bess Bligh (age 22) were married. She the daughter of Edward Bligh 5th Earl Darnley and Emma Jane Parnell Countess Darnley.

On 06 Jun 1857 King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway (age 28) and Queen Sophia of Sweden and Norway (age 20) were married. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King George II of Great Britain and Ireland.

Before 06 Jun 1864 Richard Burdon Sanderson (age 72) and Elizabeth Sanderson (age 67) were married.

On 06 Jun 1878 William Waldorf Astor 1st Viscount Astor (age 30) and Mary Dahlgren Paul (age 20) were married.

On 06 Jun 1878 Henry Howard-Molyneux-Howard (age 27) and Mabel Harriet McDonnell were married. She the daughter of Mark Kerr aka McDonnell 5th Earl of Antrim and Jane Macan Countess of Antrim (age 53).

On 06 Jun 1885 William Parker 2nd Baronet (age 60) and Jane Constance Biddulph were married. They were first cousins.

On 06 Jun 1889 Harry Lloyd Verney (age 17) and Joan Elizabeth Mary Cuffe were married. She the daughter of Hamilton John Agmondesham Cuffe 5th Earl of Desart (age 40).

On 06 Jun 1893 Robert Gresley 11th Baronet (age 27) and Frances Louisa Spencer-Churchill Lady Gresley (age 22) were married at St Margaret's Church, Westminster [Map]. She by marriage Lady Gresley of Drakelow in Derbyshire. She the daughter of George Charles Spencer-Churchill 8th Duke of Marlborough and Albertha Frances Anne Hamilton Duchess of Marlborough (age 46). She a great x 5 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

Before 06 Jun 1929 Edward Claud Berkeley Fitzharding 5th Viscount Portman (age 31) and Sybil Mary Douglas Pennant Viscountess Portman (age 42) were married. They were fourth cousins.

Deaths on the 6th June

On 06 Jun 810 Rotrude Carolingian (age 35) died.

On 06 Jun 1097 Agnes Poitiers Queen Consort Aragon Queen Consort Pamplona (age 25) died.

On 06 Jun 1217 Henry I King Castile (age 13) Was killed by a tile falling of a roof. He was buried at Abbey of Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas. His sister Berengaria Ivrea I Queen Castile (age 38) succeeded I Queen Castile.

On 06 Jun 1237 John Dunkeld 9th Earl Huntingdon 7th Earl Chester (age 30) died. Matthew Paris suggests he was poisoned by his wife Elen ferch Llewellyn Aberffraw Countess Huntingdon and Mar (age 19). Earl Huntingdon extinct. Earl Chester merged with the Crown .

On 06 Jun 1241 John Gifford (age 61) died at Dorchester on Thames, Oxfordshire [Map].

On 06 Jun 1251 William Dampierre III Count Flanders (age 27) died. His brother Guy Dampierre Count Flanders (age 25) succeeded Count Flanders.

On 06 Jun 1271 Robert Neville (age 34) died at Raby Castle, County Durham [Map].

On 06 Jun 1304 Maria Burgundy (age 39) died.

On 06 Jun 1333 William Donn Burgh 3rd Earl Ulster (age 20) was murdered by Richard de Mandeville in revenge for the murder of Richard's wife's brother Walter Liath de Burgh the year before. Baron Burgh extinct.

On 06 Jun 1349 William Harcourt (age 49) died of plague at Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire [Map].

On 06 Jun 1411 Isabella aka Elizabeth Julich Countess Kent (age 81) died.

On 06 Jun 1414 John Stanley (age 64) died at Ardee, Louth, County Louth. He was buried at Burscough Priory [Map].

On 06 Jun 1441 William Phelip (age 58) died. He was buried at St Mary's Church, Dennington [Map]. Monument to William Phelip (age 58) and Joan Bardolf (age 50). Early Plate Bascinet and Gorget Period. Feathered Crest. Detail of the Wyvern on which her feet rest. Detail of Eagle, possibly hawk, on which his feet rest. Crespine Headress covering her hair. He wearing a bascinet with IHC NASARE Lettering. Both wearing a Lancastrian Esses Collar. Leg Garter below the left knee.

On 06 Jun 1464 Edward Brooke 6th Baron Cobham (age 49) died at Cobham, Kent. He was buried at Cobham, Kent. His son John Brooke 7th Baron Cobham (age 16) succeeded 7th Baron Cobham.

On 06 Jun 1466 John Welles (age 58) died.

Before 06 Jun 1474 Anne Holland (age 13) died.

On 06 Jun 1482 Nicholas Griffin 8th Baron Latimer Braybrooke (age 56) died. His son John Griffin 9th Baron Latimer Braybrooke (age 32) de jure 9th Baron Latimer of Braybrook.

On 06 Jun 1484 Ann Hoo (age 59) died.

On 06 Jun 1494 John Cheney (age 51) died at Cralle Manor Warbleton.

After 06 Jun 1540 Edward Maxwell died.

On 06 Jun 1545 Philip Boteler (age 53) died.

On 06 Jun 1555 John Talbot (age 42) died.

On 06 Jun 1557 Robert Stapleton (age 40) died.

On 06 Jun 1557 John Port (age 47) died.

On 06 Jun 1559 Richard Alleyne of Grantham (age 69) died.

On 06 Jun 1561 Catherine of Mecklenburg Duchess of Saxony (age 74) died.

On 06 Jun 1571 William Sneyd of Bradwell Cheshire (age 59) died.

On 06 Jun 1572 Elizabeth Conyers (age 27) died.

On 06 Jun 1642 Robert Digby 1st Baron Digby (age 43) died. His son Kildare Digby 2nd Baron Digby (age 11) succeeded 2nd Baron Digby of Geashill in County Offaly.

On 06 Jun 1675 Henri Bourbon Condé (age 2) died.

On 06 Jun 1676 Jane Savage Baroness Chandos (age 50) died.

On 06 Jun 1695 Frances Savile (age 37) died.

On 06 Jun 1735 Peter Vavasour (age 68) died.

On 06 Jun 1741 Norton Powlett (age 60) died.

On 06 Jun 1743 Richard Fitzwilliam 5th Viscount Fitzwilliam (age 66) died. His son Richard Fitzwilliam 6th Viscount Fitzwilliam (age 31) succeeded 6th Viscount Fitzwilliam of Mount Merrion House in Dublin.

On 06 Jun 1759 Bluett Wallop (age 33) died of smallpox.

On 06 Jun 1762 George Anson 1st Baron Anson (age 65) died without issue at Moor Park, Hertfordshire. He was buried at St Michael and All Angels Church, Colwich [Map]. Baron Anson of Soberton in Southampton extinct. His brother Thomas Anson (age 67) inherited his estates.

On 06 Jun 1786 Hugh Percy 1st Duke Northumberland (age 70) died. His son Hugh Percy 2nd Duke Northumberland (age 43) succeeded 2nd Duke Northumberland, 2nd Baron Lovain, 5th Baronet Smithson of Stanwick in Yorkshire. Frances Julia Burrell Duchess Northumberland (age 33) by marriage Duchess Northumberland.

On 06 Jun 1804 Robert Cholmondeley (age 76) died.

On 06 Jun 1808 Martha Venables-Vernon (age 56) died.

On 06 Jun 1814 Katherine Frances Montagu Scott (age 10) died.

On 06 Jun 1814 John Montagu 5th Earl Sandwich (age 70) died. He was buried at All Saints Church, Barnwell [Map]. His son George Montagu 6th Earl Sandwich (age 41) succeeded 6th Earl Sandwich. Louisa Lowry-Corry Countess of Sandwich (age 33) by marriage Countess Sandwich.

On 06 Jun 1824 Robert Sewallis Shirley (age 45) died.

On 06 Jun 1832 Elizabeth Carew died.

On 06 Jun 1847 Sarah Bowes-Lyon (age 33) died.

On 06 Jun 1849 Henrietta Callender Grant (age 47) died.

On 06 Jun 1850 Emily Cavendish-Bentinck died.

On 06 Jun 1855 George Frederick Dawson (age 28) died.

On 06 Jun 1855 Elizabeth King (age 28) died.

On 06 Jun 1857 Frederick Pleydell-Bouverie (age 71) died.

On 06 Jun 1864 Elizabeth Sanderson (age 67) died.

On 06 Jun 1867 Caroline Tollemache (age 38) died.

On 06 Jun 1872 Augusta Paget Baroness Templemore (age 70) died.

On 06 Jun 1886 Henry Paul Lindley Wood (age 7) died.

On 06 Jun 1888 Edward Henry Gervase Stracey 6th Baronet (age 49) died. His son Edward Paulet Stracey 7th Baronet (age 16) succeeded 7th Baronet Stracey of Rackheath in Norfolk.

On 06 Jun 1911 Reverend Arthur William Tryon (age 61) died.

On 06 Jun 1913 Anne Agnes Barker died.

On 06 Jun 1925 Julia Stanton Viscountess Dillon died.

On 06 Jun 1926 Harriet Dumaresq Baroness St Owsald died.

On 06 Jun 1928 Robert "Bobby" Francis Kennedy (age 2) was assassinated.

On 06 Jun 1928 Captain Ralph Frederick Vane (age 36) died. He has a memorial at St Mary's Church, Staindrop [Map].

Captain Ralph Frederick Vane: On 08 Jun 1891 he was born to Henry de Vere Vane 9th Baron Barnard and Catherine Sarah Cecil Baroness Barnard.

On 06 Jun 1929 Claud Berkeley Fitzharding 4th Viscount Portman (age 64) died. His son Edward Claud Berkeley Fitzharding 5th Viscount Portman (age 31) succeeded 5th Viscount Portman, 5th Baron Portman. Sybil Mary Douglas Pennant Viscountess Portman (age 42) by marriage Viscountess Portman.

On 06 Jun 1935 Julian Hedworth George Byng (age 72) died.

On 06 Jun 1950 Charles Robinson Sykes (age 74) died.

On 06 Jun 1951 Major Lionel Hallam Tennyson 3rd Baron Tennyson (age 61) died. His son Harold Tennyson 4th Baron Tennyson (age 32) succeeded 4th Baron Tennyson of Aldworth in Sussex and of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight.

On 06 Jun 1954 Margaret Crichton-Stuart (age 78) died.

On 06 Jun 1956 Edith Amelia Ward Baroness Wolverton (age 83) died.

On 06 Jun 1962 Muriel Ivy Gladstone Baroness Hollenden died.

On 06 Jun 1968 Randolph Church (age 57) died.

On 06 Jun 1972 John Edward Reginald Wyndham 6th Baron Leconfield 1st Baron Egremont (age 52) died. His son John Wayndham 7th Baron Leconfield 2nd Baron Egremont (age 24) succeeded 7th Baron Leconfield of Leconfield in the East Riding of Yorkshire, 2nd Baron Egremont.

On 06 Jun 1983 Ambrose Coghill 7th Baronet (age 80) died. His son Egerton "Toby" Coghill 8th Baronet (age 53) succeeded 8th Baronet Coghill of Coghill Hall in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

On 06 Jun 1999 Nancy Beaton (age 89) died.

On 06 Jun 2006 Leslie Alcock (age 81) died.