On this Day in History ... 15th April

15 Apr is in April.

1477 Trial and Execution of Ankarette Twynyho

1533 Anne Boleyn's First Appearance as Queen

1533 Catherine Aragon Demoted to Princess

1551 Sweating Sickness Outbreak

1641 Trial and Execution of the Earl of Strafford

1690 Invitation to William of Orange from the Immortal Seven

Events on the 15th April

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 15 Apr 1053. In this year was the king (age 50) at Winchester, Hampshire [Map], at Easter; and Earl Godwin (age 52) with him, and Earl Harold (age 31) his son, and Tosty (age 27). On the day after Easter sat he with the king at table; when he suddenly sunk beneath against the foot-rail, deprived of speech and of all his strength. He was brought into the king's chamber; and they supposed that it would pass over: but it was not so. He continued thus speechless and helpless till the Thursday; when he resigned his life, on the seventeenth before the calends of May; and he was buried at Winchester in the old minster. Earl Harold (age 31), his son, took to the earldom that his father had before, and to all that his father possessed; whilst Earl Elgar took to the earldom that Harold (age 31) had before. The Welshmen this year slew a great many of the warders of the English people at Westbury, Wiltshire [Map]. This year there was no archbishop in this land: but Bishop Stigand held the see of Canterbury at Christ church, and Kinsey that of York. Leofwine and Wulfwy went over sea, and had themselves consecrated bishops there. Wulfwy took to the bishopric which Ulf had whilst he was living and in exile.

Chronica Majora. Around 15 Apr 1237. About the same time, the emperor Frederick (age 42), finding that the malice of his enemies had recalled him to Germany from his intended expedition, and that, to his disgrace, he was obliged to raise the siege and retire from Milan instituted an inquiry as to who had caused him this obstruction, and finding that the duke of Austria had stirred up internal discord in Germany, and that he was the cause of his being hindered in his purpose, attacked him and deprived him of his lands, honours, and wealth.

On 15 Apr 1367 King Henry IV of England was born to John of Gaunt 1st Duke Lancaster (age 27) and Blanche Plantagenet Duchess Lancaster (age 22) at Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire [Map]. He a grandson of King Edward III of England.

On 15 Apr 1393 Elizabeth Pomerania Holy Roman Empress Luxemburg (age 46) died.

On 15 Apr 1450 the Battle of Formigny was a descisive victory for the French that destroyed the England's last army in France bringing to end English control of Normandy.

Charles Bourbon I Duke Bourbon (age 49) and Arthur Montfort III Duke Brittany (age 56) commanded the French. The English commander Thomas Kyriell (age 54) was captured.

The battle is considered to be one of the first where cannon played a decisive role.

On 12 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho was arrested at Keyford, Somerset and taken to Bath, Somerset [Map]. George York 1st Duke of Clarence (age 27) believed she had murdered his wife Isabel Neville Duchess Clarence who had died four months before.

On 13 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho taken to Cirencester, Gloucestershire [Map].

On 15 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho and John Thursby were hanged at Myton Gallows, Warwick [Map].

After 15 Apr 1526. St Helen's Church Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire [Map]. Floor slab to Robert Nundi Tailor died 15 Apr 1526. On his death he left bequests to the mother church of Lincoln and to several local religious houses. He also left money for a mass to be said regularly in his memory. His land and property in Ashby was left in the casre of his wife until his son Richard came of age.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

The King (age 41) has this very day dispatched a courier to Rome. I fancy it is for the purpose of telling the Pope that whatever has been attempted in this Parliament against him and his authority has been done at the solicitation of his people, not at his own, and that should his new marriage be ratified and sanctioned he is ready to revoke everything. He has forbidden the courier to carry any other letters but his, that the truth may not be found out. Your Majesty, however, might tell His Holiness how matters stand, and urge him to sentence the case and make all other necessary provisions.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

Every day numbers of people come to my hotel and inquire from my servants and neighbours how long I intend remaining here in London, for until the hour of my departure many will go on thinking that Your Majesty consents to this marriage, without which condition no one thinks that this King (age 41) would have dared to proceed to such extremities. For this cause I think I ought to be immediately recalled, and most humbly beseech Your Majesty to send the order; not so much to avoid the dangers and troubles that may supervene, for I should consider myself happy to sacrifice my life for the Imperial service, but merely for the above-named considerations, &c.-London, 15th April 1533.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

The name and title which the King (age 41) wishes the Queen (age 47) to take, and by which he orders the people to call her, is the old dowager princess (la vielle et vefve princesse). As to princess Mary (age 17) no title has yet been given to her, and I fancy they will wait to settle that until the Lady (age 32) has been confined (que la dame aye faict lenfant).

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

On Wednesday the said Duke (age 60), and the others of whom I wrote to Your Majesty in my last despatch, called upon the Queen (age 47) and delivered their message, which was in substance as follows: "She was to renounce her title of Queen, and allow her case to be decided here, in England. If she did, she would confer a great boon on the kingdom and prevent much effusion of blood, and besides the King (age 41) would treat her in future much better than she could possibly expect." Perceiving that there was no chance of the Queen's (age 47) agreeing to such terms, the deputies further told her that they came in the King's name to inform her that resistance was useless (quelle se rompist plus la teste), since his marriage with the other Lady had been effected more than two months ago in the presence of several persons, without any one of them having been summoned for that purpose. Upon which, with much bowing and ceremony, and many excuses for having in obedience to the king's commands fulfilled so disagreeable a duty, the deputies withdrew. After whose departure the lord Mountjoy (age 55), the Queen's (age 47) chamberlain, came to notify to her the King's intention that in future she should not be called Queen, and that from one month after Easter the King (age 41) would no longer provide for her personal expenses or the wages of her servants. He intended her to retire to some private house of her own, and there live on the small allowance assigned to her, and which, I am told, will scarcely be sufficient to cover the expenses of her household for the first quarter of next year. The Queen (age 47) resolutely said that as long as she lived she would entitle herself Queen; as to keeping house herself, she cared not to begin that duty so late in life. If the King (age 41) thought that her expenses were too great, he might, if he chose, take her own personal property and place her wherever he chose, with a confessor, a physician, an apothecary, and two maids for the service of her chamber; if that even seemed too much to ask, and there was nothing left for her and her servants to live upon, she would willingly go about the world begging alms for the love of God.

Though the King (age 41) is by nature kind and generously inclined, this Anne has so perverted him that he does not seem the same man. It is, therefore, to be feared that unless Your Majesty applies a prompt remedy to this evil, the Lady (age 32) will not relent in her persecution until she actually finishes with Queen Catharine (age 47), as she did once with cardinal Wolsey, whom she did not hate half as much. The Queen (age 47), however, is not afraid for herself; what she cares most for is the Princess (age 17).

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

About a week ago the sieur de Rochefort (age 30) (George Boleyn) returned from France with the sieur de Beauvoes (Beauvoir), who started yesterday for Scotland for the purpose of inducing king James to place his differences with this King (age 41) into his master's hand, and making him judge and arbiter of their differences. I have been told by a very worthy man that the duke of Albany's secretary returning from a visit to the said Beaulvoys (sic) had assured him that the said ambassador would be unable to accomplish his mission in Scotland, and that war would go on fiercer than ever. Indeed it would seem as if the Scots at this moment more prosperous than ever, for instead of being as before on the defensive, they are continually making raids on the borders. For this purpose did Mr. de Rocchefort (age 30) go to France as it is now ascertained. These people, as I am told, wish immensely for peace with Scotland, but God, as I said above, has taken away their senses, and they cannot see how to bring it about. The said Mr. de Rocchefort (age 30), as his own servants assert, has been presented in France with 2,000 crs., no doubt for the good tidings of his sister's (age 32) marriage, to whom the Most Christian King has now written a letter addressing her as Queen. I fancy, moreover, that the French consider this good news, firstly: because it is likely to be the means of breaking off the friendship between Your Majesty and this king, and also, because it might ultimately be the cause of freeing the French from their debt and payment of pensions, either through sheer necessity, or for fear these people may have of their ultimately joining you, should the Pope proceed to sentence the case and have the censures executed-a thing which, in my opinion, Your Majesty ought to urge in every possible way-the French would be released from all their bonds and pecuniary obligations to this king.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

A deputation of English merchants trading with Flanders went on Friday last to see the King (age 41) for the purpose of ascertaining whether they could in future ship goods for that country. They were told that the King (age 41) was not at war with Your Majesty, and that they might trade or not just as they pleased; those who had any scruple might remain at home; those who chose to go on with their trade might do so. Not-withstanding which answer there is hardly any English or foreign merchants having goods in Flanders who has not sent for them, or had them put under another name (les couvrir), for there is hardly one who does not consider himself lost and ruined, and would not wish himself far off with his goods and substance. Indeed this fear is not confined to the merchants, but pervades all classes of society, and I have been told that Cramuel (age 48) (Cromwell), who is perhaps the man who has most influence with the King (age 41) just now, has had all his treasure and valuables removed to the Tower of London. And I do really believe that neither the King (age 41) himself nor any of his courtiers is exempt from fear, both of the people and of Your Majesty; yet it would seem as if God Almighty has blinded them, and taken away their senses, for they are perfectly bewildered and know not what to be at, nor how to mend their affairs. Indeed this is so much the case, that should the least mishap overtake them they would be so disconcerted that neither the King (age 41) nor his counsellors would think of aught else than flight, knowing very well the people's will in these matters.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

On Saturday, the eve of Easter, Lady Anne (age 32) went to mass in truly Royal state, loaded with diamonds and other precious stones, and dressed in a gorgeous suit of tissue, the train of which was carried by the daughter (age 14) of the duke of Norfolk (age 60), betrothed to the Duke of Richmond (age 13). She was followed by numerous damsels, and conducted to and from the church [Map] with the same or perhaps greater ceremonies and solemnities than those used with former Queens on such occasions. She has now changed her title of marchioness for that of Queen, and preachers specially name her so in their church prayers. At which all people here are perfectly astonished, for the whole thing seems a dream, and even those who support her party do not know whether to laugh or cry at it. The King (age 41) is watching what sort of mien the people put on at this, and solicits his nobles to visit and pay their court to his new Queen, whom he purposes to have crowned after Easter in the most solemn manner, and it is said that there will be banqueting and tournaments on the occasion. Indeed some think that Clarence, the king-at-arms who left for France four days ago, is gone for the purpose of inviting knights for the tournament in imitation of the Most Christian King when he celebrated his own nuptials. I cannot say whether the coronation will take place before or after these festivities, but I am told that this King (age 41) has secretly arranged with the archbishop of Canterbury (age 43), that in virtue of his office, and without application from anyone he is to summon him before his court as having two wives, upon which, without sending for the Queen (age 47), he (the Archbishop) will declare that the King (age 41) can lawfully marry again, as he has done, without waiting for a dispensation, for a sentence from the Pope, or any other declaration whatever.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

We both returned [to London] without accepting the pressing invitation to dinner from the earl of Wulchier (age 56) (Wiltshire) who in the absence of the duke of Norfolk was to preside at the table.

Letters and Papers 1533. 15 Apr 1533. 351. On Saturday, Easter Eve, dame Anne (age 32) went to mass in Royal state, loaded with jewels, clothed in a robe of cloth of gold friese. The daughter (age 14) of the duke of Norfolk (age 60), who is affianced to the duke of Richmond (age 13), carried her train; and she had in her suite sixty young ladies, and was brought to church, and brought back with the solemnities, or even more, which were used to the Queen. She has changed her name from Marchioness to Queen, and the preachers offered prayers for her by name. All the world is astonished at it for it looks like a dream, and even those who take her part know not whether to laugh or to cry. The King is very watchful of the countenance of the people, and begs the lords to go and visit and make their court to the new Queen, whom he intends to have solemnly crowned after Easter, when he will have feastings and tournaments; and some think that Clarencieux went four days ago to France to invite gentlemen at arms to the tourney, after the example of Francis, who did so at his nuptials. I know not whether this will be before or after, but the King has secretly appointed with the archbishop of Canterbury that of his office, without any other pressure, he shall cite the King as having two wives; and upon this, without summoning the Queen, he will declare that he was at liberty to marry as he has done without waiting for a dispensation or sentence of any kind.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

On Tuesday the 7th inst., having been informed of the strange and outrageous conduct and proceedings of this king (age 41) against the Queen (age 47), whereof I have written to Your Majesty, I went to Court at the hour appointed for the King's audience, that I might there duly remonstrate against the Queen's treatment. I took with me Mr. Hesdin, who by the consent of the Queen [of Hungary] is now here to claim the arrears of his pension, in order that he might be present, and hear the remonstrances I had to address the King (age 41), hoping also that if I had to use threatening language the King (age 41) might not be so much offended if uttered in the presence of the said Hesdin. On my arrival at Greenwich [Map] the earl of Vulchier (age 56) (Wiltshire) came to meet me, and leading me to the apartments of the duke of Norfolk (age 60), who had just gone to see the Queen (age 47), said to me that the King (age 41) being very much engaged at that hour had deputed him to listen to what I had to say, and report thereupon. My answer was that my communication was of such a nature and so important that I could not possibly make it to anyone but to the King (age 41) in person. Until now he had never refused me audience, or put me off, and I could not think that he would now break through the custom without my having given him any occasion for it, especially as the King (age 41) knew that Your Majesty most willingly received the English ambassadors at all hours, whatever might be their errand or business. The Earl (age 56) repeated his excuses, and seemed at first disinclined to take my answer back to the King (age 41), until at last, perceiving my firm determination, he went in and came back saying the King (age 41) would see me immediately, though he still tried to ascertain what my business was, and advised me to put off my communication until after the festivals. It was settled at last that I should see the King (age 41) on Thursday in Holy Week, on which day having about me a copy of my last despatch [to Your Majesty], I took again the road to Court, accompanied as before by the said Master Hesdin, and was introduced to the Royal presence by the same earl of Wiltshire (age 56). The King (age 41) received us graciously enough. After the usual salutations and inquiries about Your Majesty's health, the King (age 41) asked me what news I had of your movements. I answered that the letters I had received last were rather old, but that I had reason to believe you had already embarked to return to Spain at the beginning of this present month. This statement the King (age 41) easily believed, and was rejoiced to hear (such is his wish to see you fairly out of Italy). I added that the weather for the last days could not have been more favourable, and therefore that it was to be hoped Your Majesty had reached Spain in safety. Having then asked me whether I had other news to communicate, I told him that your brother, the king of the Romans (age 30), had made his peace with the Turk, and that the latter had sent an embassy, at which piece of intelligence the King (age 41) remained for some time in silent astonishment as if he did not know what to answer.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

Lastly, upon my urging upon him that his marriage had been pre-arranged by the King, his father [Henry VII.], and by the Catholic king of Spain [Ferdinand], both of whom were the wisest of their age, and would have never consented to it had there been the least shade of scruple respecting Prince Arthur - which after all was the principal ground of complaint - he again insisted on his determination to act as he pleased in the matter without attending to considerations of any sort whatever, adding that you yourself had shewn him the way to disobey the Pope's injunctions by your appealing four years ago to a future Council. Upon which I told him that he himself could not do better than follow your example and appeal to that very Council, and since he alleged that he was ready to imitate you in this respect, I must warn him that no prince in the world had more respect than you had for His Holiness, or deeper fear of his excommunications, for upon one occasion you had been one whole Holy Week without attending Divine service.

These last words of mine had great effect upon the King (age 41), who no doubt thought that I meant to reproach him for not having obeyed the Papal excommunication and interdict once fulminated against him; he, therefore, was a little hurt and said to me in rather an angry tone of voice: "If you go on like that you will make me lose my temper." I begged him to tell me how I could have offended him, warmly protesting that I had no such intention; then he lowered his voice a little and spoke less harshly, though, notwithstanding all my entreaties, he would never say how or in what I had offended him, and I must say that the rest of our conference passed without any visible signs of ill-humour on his part.

Thus encouraged I asked him whether in the event of Spaniards and Flemings, as good Christians, refusing for fear of the Papal interdict to hold communication, or carry on trade with his subjects, they would be amenable to the penalties described in the statute, and what sort of crime could be imputed to them. He remained for a while thoughtful and startled, not knowing what to answer, which being observed by me I preferred asking leave to retire to remaining where I was and waiting for his answer. I, therefore, said to him: "If such be the state of things I will not trouble Your Highness any more and lose my time; I will withdraw." He then said "adieu" to me in a gracious manner, but retained Hesdin, to whom he addressed the following words; "You have heard what the Emperor's ambassador has just said respecting the Papal excommunication and the stopping of trade between my subjects and the Spaniards and Flemings; but I can tell you that the ecclesiastical censures do not on this occasion fall upon me, but upon the Emperor himself who has so long opposed me, and prevented my new marriage, thus making me live in sin and against the prescriptions of Mother Church. The excommunication, moreover, is of such a nature that the Pope himself could not raise it without my consent; but, pray, do not mention this to the ambassador." This will give Your Majesty an idea of the King's blindness in these matters. Hesdin only replied that the affair was of too much importance for him to mix himself up with it.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

After this we came to speak about the Queen (age 47) and to argue whether she had or had not been known by Prince Arthur, and after responding victoriously to the suppositions and conjectures which he alleged in support of his opinion, I produced such arguments in proof of the contrary that he really knew not what to answer. Which arguments having been brought forward on more than one occasion I will not trouble Your Majesty with a reproduction of them, and will only say "que venant a reprendre le dit seigneur roy ce que plusieurs fois il auoit confesse, que la royne demeura pucelle du dit prince Arthus, et voyant quil ne le pouvoit nyer, il dit quil lauoit plusieurs fois dit mais que ce nauoit este que en ieu, et que lhome en iouant et banquetant dit souvent pluseures (sic) choses que ne sont veritables." Having said as much as if he had obtained a great success, or found some subtle point towards the gaining of his cause, he began to recover his self-possession and said confidently to me: "Now I think I have given you full satisfaction on all points; what else do you want?" Whatever the King (age 41) might say the satisfaction was not all-sufficing, but it served me admirably, much more than he himself could imagine, to dispute certain premises he had laid down. I told him that I flattered myself that I was the ambassador of the prince who desired most his welfare, profit, and honour, as well as the tranquillity of his kingdom. I had brought with me Master Hesdin, there present, who was, and acknowledged himself to be, his affectionate servant- as did also all Your Majesty's officers-that he might be present at the conference and hear what his answer was; but I would promise most solemnly that nothing that might be said at that audience should be reported to you unless he himself wished, for I consented to the said Hesdin giving me the lie if I ever attempted to write to Your Majesty anything he (the King) did dislike. This I said to the King (age 41) that I might inspire greater confidence and make him open his heart more fully (lui fere deslier le sac). The better to gain his confidence I told him how happy I had once considered myself at being chosen by Your Majesty to represent your person near so great and magnanimous a king, hoping that his Privy Council, taking due cognizance of the affairs pending between the two crowns, everything should go on smoothly. Now, on the contrary, affairs had taken such a disorderly turn, and were in such confusion that I considered myself unhappy in having to represent Your Majesty, inasmuch as I had continually assured you in my despatches that whatever countenance the King (age 41) put on, and whatever he did his heart and the affection he bore Your Majesty were not affected, and that he would never think of doing anything that might give occasion to suspect that he intended living otherwise than in peace and amity with Your Imperial Majesty. At these words, and without waiting to hear the rest, as if he wished to avoid alt further conversation on this delicate subject, the King (age 41) frowned, and moving his head to and fro, said rather abruptly: "Before I listen to such representations, I must know from whom they proceed, whether from the Emperor, your master, or from yourself; for if they be private remarks of your own I shall know how to answer them." And upon my answering that it was superfluous to ask whether I could have received commission to complain of facts and things which had only taken place a week ago, the intelligence of which would require a full month to be transmitted, and perhaps, too, four successive despatches of mine before it was believed-my general charge and instructions being to maintain by all best means the peace and friendship between Your Majesty and him, and especially to watch over the Queen's (age 47) affairs, since from them depended in a great measure that very friendship-the King (age 41) replied that you yourself had nothing to do with the laws, statutes, and constitutions of his kingdom, and that in spite of all opposition he would pass such laws and ordinances in his dominions as he thought proper, adding many other things in the same strain. My reply was that Your Majesty neither could nor would hinder any such legislative measures, but on the contrary would, if necessary, help him in them unless they personally affected the Queen (age 47), whom he wanted to compel to renounce her appeal [to Rome] and submit entirely to the judgment of the prelates of his kingdom who, either won by promises or threatened with that punishment which had already attained those who upheld the Queen's (age 47) right, could not fail to decide in his favour and against her. After this I repeated what I had told him on previous occasions in Your Majesty's name, that is to say: that the fact of the case being determined here, in England, as he wished, would in nowise remove hereafter the doubts about the succession for the reasons above explained, He, himself, considering how unreasonable and illegal it would be to have the case tried and decided in England, when the authority of the Holy Apostolic See was concerned, had from the beginning of the suit asked the Papal permission for the two cardinals (Campeggio (age 58) and York) to take cognizance of the case here. Even after that he had allowed the Queen (age 47) to appeal to Rome, and in the course of time not satisfied with that had himself, and through others, solicited the Queen (age 47) to consent to the case being tried out of Rome, not here in England, for he knew that to be a most unreasonable demand, but in a neutral place. For these reasons I said the Queen (age 47) cannot and ought not to be tied by laws and statutes to which no one hardly had consented, and which had been carried by compulsion. To this remark of mine the King (age 41) replied half in a passion (demy appassione): "All persuasions and remonstrances are absolutely in vain. Had I known that the audience you applied for had no other object than to speak to me of these things I certainly should have found some excuse to break through the established rule, and escape from such objurgations." But on my representing to him the object of my calling, and telling him that he was positively bound to listen not only to what an ambassador of Your Majesty, but the commonest mortal, had to say to him in a case of this sort, and the courteous and humane manner in which you had always treated his ambassadors, he was obliged to retract, and said that as regarded the commission granted to the two cardinals he could not deny that he himself had applied for it, but that was, he said, under a promise made by the Pope that the cause should never be revoked [from England]; but since His Holiness withdrew all the commissions he had previously given, he (the King) did likewise reject the offer to have the case tried and sentenced in a neutral place, for he wished it to be determined here and not elsewhere. As to his consent to the Queen's (age 47) appeal he had only given it conditionally, and provided the statutes and constitutions of the kingdom allowed of it, not otherwise, and said that lately a prohibitive one had been made in Parliament which the Queen (age 47) herself, as an English subject, was bound to obey. Hearing this I could not help observing that laws and constitutions had no retroactive power, and that they could only be enforced in the future. As to the Queen (age 47) being an English subject I owned that she being his legitimate wife was really and truly such, and that consequently all debate about constitutions and appeals was not only superfluous but out of the question; but that if the Queen (age 47), however, was, as he asserted, not his wife, she could not be called an English subject, for she only resided in this country in virtue of her marriage, not otherwise, and Common Law establishes that the claimant is to bring his action before the tribunal of the country whereof the defendant is a native. The Queen (age 47) might as well ask to have her case tried in Spain, but this she had never attempted, contenting herself that the court to which he himself had firstly applied as claimant should take cognizance of the affair, that being the only true and irrefragable tribunal in her case. And upon his replying that he had not sent for her, and that his brother, the prince of Wales, had first taken her to wife and consummated marriage, I remarked that if he himself had not sent for her he had after his brother's demise kept her by him, and prevented her from going away at the request of her father, the Catholic king of Spain, through his ambassador at this court, Hernand Duque de Estrada, as I could prove by his letters. These, however, the King (age 41) refused to peruse, and again repeated: "She must have patience and obey the laws of this kingdom." Then he added that Your Majesty in return for so many services and favours had done him the greatest possible injury by hindering his new marriage, and preventing his having male succession. That the Queen (age 47) was no more his wife than she was mine, and that he would act in this business just as he pleased, in spite of all opposition and grumbling, and that if Your Majesty capriciously attempted to cause him annoyance he would try to defend himself with the help of his friends.

Calendars. 15 Apr 1533. 1061. Eustace Chapuys (age 43) to the Emperor (age 33).

After this, coming to the principal object of my visit, I told him plainly that, although for several days past I had heard of the attempt made both at the convocation of the prelates and in Parliament to impugn the Queen's (age 47) rights, and greatly injure her just cause, I had taken no notice of the facts, inasmuch as I could not be persuaded that so wise, virtuous, and Catholic a prince could possibly authorize or sanction such things, and also because I thought and believed that such practices (menees) could in no wise impair the Queen's (age 47) right or cause her harm. Yet that having lately been apprized from various quarters that such an attempt was really being made, I considered that I could not acquit myself of my duty towards God, towards Your Imperial Majesty, and towards himself if I did not remonstrate at once against such behaviour, and entreat him by his virtue, wisdom, and humanity patiently to listen to my observations as proceeding from my desire for his service, for that though he might disregard and despise man, he would at least respect God. To which the King (age 41) answered that so he had done, and that God and his conscience were perfectly agreed on that point.

Hearing the King (age 41) express himself in this manner and wishing to bring him back to the subject as gently as possible, I observed that my colleague and I could not but be very much flattered at the familiar way in which he had expressed his sentiments, as if we were his own servants, which sentiments, I added, proceeded no doubt from his heart not from his mouth. He assured me, however, that such was not the case, and that what he had just said had been said without dissimulation. Upon which I again said to him that I could not believe that Christianity, being so agitated and troubled by heresies, he could possibly set so bad an example and contravene the treaties of peace and amity which, as he himself, who had been the principal promoter and mediator in them ought to know best, had cost so much time and trouble to make. He ought to know that even supposing no inconvenience arose therefrom in his lifetime there would be most serious ones after his death with regard to the succession. There had never been such a case, I continued, nor did we read of it in history, as for a prince to divorce his legitimate wife after five and twenty years, and marry another woman. Not knowing what to answer to my observations, the King (age 41) gladly seized the opportunity which I gave him by this last statement to contradict me, and said: "Not so long, if you please; and if the world finds this new marriage of mine strange, I find it still more so that the Pope [Julius] should have granted a dispensation for the former." I then mentioned to him five popes who had dispensed in similar cases, and declared that I was unwilling to dispute that matter with him, but that there was no doctor in his kingdom, who after such a debate would not confess that pope Julius was authorized to dispense in the case. After this, coming to speak about the manner in which his solicitors had procured the votes of the university of Paris, on which he founds his principal argument, I offered to produce the letters I had received relating the whole affair, as well as the names of those who had held for the Queen (age 47), but he said there was no necessity at all for that. I, moreover, told him that neither in Spain, nor in Naples, nor in any other country could one single prelate or doctor be found to assert the contrary, and that even in his own kingdom every canonist and lawyer was of the same opinion, with the exception of the few who had been gained over to the other side, and I proposed, in confirmation of my statement, to exhibit other letters, which he likewise refused to see.

At last, wishing to turn the conversation, the King (age 41) said that he wished to ensure the succession to his kingdom by having children, which he had not at present, and upon my remarking to him that he had one daughter, the most virtuous and accomplished that could be thought of, just of suitable age to be married and get children, and that it seemed as if Nature had decided that the succession to the English throne should be through the female line, as he himself had obtained it, and therefore, that he could by marrying the Princess to some one secure the succession he was so anxious for, he replied that he knew better than that; and would marry again in order to have children himself. And upon my observing to him that he could not be sure of that he asked me three times running: "Am I not a man like others?" and he afterwards added: "I need not give proofs of the contrary, or let you into my secrets," no doubt implying thereby that his beloved Lady (age 32) is already in the family way.

Annales of England by John Stow. The 15 of April, the infections sweating sicknesse began at Shrewsbury, Shropshire [Map], -- which ended not in the North part of England untill the ende of September. "In this space what number died, it cannot be well accompted, but certaine it is that in London in fewe daies 960. gave up the ghost: if began in London the 9. of July, and the 12. of July it was most vehement, which was so terrible, that people being in best health, were sodainly taken, and dead in foure and twenty houres, and twelve, or lesse, for lacke of skill in guiding them in their sweat. And it is to be noted, that this mortalitie fell chiefely or rather on men, and those also of the best age, as betweene thirty and forty yeares, fewe women, nor children, nor olde men died thereof. Sleeping in the beginning was present death, for if they were suffered to sleepe but half a quarter of an houre, they never spake after, nor had any knowledge, but when they wakened fell into panges of death. This was a terrible time in London, for many one lost sodainly his friends, by the sweat, and their money by the proclamation. Seven honest householders did sup together, and before eight of the clocke in the next morning, four them were dead: they that were taken with full stomacks escaped hardly . This sickenesse followed English men as well within the realme, as in strange countries: wherefore this nation was much afeard of it, and for the time began to repent and remember God but as the disease relented, the devotion deceased. The first weeke died in London 800 persons.

Evelyn's Diary. 15 Apr 1641 I repaired to London to hear and see the famous trial of the Earl of Strafford, Lord-Deputy of Ireland (age 48), who, on the 22nd of March, had been summoned before both Houses of Parliament, and now appeared in Westminster Hall [Map], which was prepared with scaffolds for the Lords and Commons, who, together with the King (age 40), Queen (age 31), Prince (age 10), and flower of the noblesse, were spectators and auditors of the greatest malice and the greatest innocency that ever met before so illustrious an assembly. It was Thomas Earl of Arundel and Surrey (age 55), Earl Marshal of England, who was made High Steward upon this occasion; and the sequel is too well known to need any notice of the event.

On 15 Apr 1646 Christian V King Denmark and Norway was born to Frederick III King Denmark (age 37) and Sophie Amalie Hanover Queen Consort Denmark (age 18).

On 15 Apr 1661 Charles Stewart 6th Duke Lennox 3rd Duke Richmond (age 22) was appointed 462nd Knight of the Garter by King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland (age 30).

Evelyn's Diary. 15 Apr 1666. Our parish was now more infected with the plague than ever, and so was all the country about, though almost quite ceased at London.

Pepy's Diary. 15 Apr 1667. Lay long in bed, and by and by called up by Sir H. Cholmly (age 34), who tells me that my Lord Middleton (age 59) is for certain chosen Governor of Tangier; a man of moderate understanding, not covetous, but a soldier of fortune, and poor. Here comes Mr. Sanchy with an impertinent business to me of a ticket, which I put off. But by and by comes Dr. Childe (age 61) by appointment, and sat with me all the morning making me bases and inward parts to several songs that I desired of him, to my great content. Then dined, and then abroad by coach, and I set him down at Hatton Garden, and I to the King's house by chance, where a new play: so full as I never saw it; I forced to stand all the while close to the very door till I took cold, and many people went away for want of room. The King (age 36), and Queene (age 57), and Duke of York (age 33) and Duchess (age 30) there, and all the Court, and Sir W. Coventry (age 39). The play called "The Change of Crownes"; a play of Ned Howard's (age 42), the best that ever I saw at that house, being a great play and serious; only Lacy (age 52) did act the country-gentleman come up to Court, who do abuse the Court with all the imaginable wit and plainness about selling of places, and doing every thing for money. The play took very much.

On 15 Apr 1690 Richard Lumley 1st Earl Scarborough (age 40) was created 1st Earl Scarborough by King William III of England, Scotland and Ireland (age 39) in recognition of his (age 40) support of the Glorious Revolution he having been one of the signatories of the Invitation to William of Orange from the Immortal Seven. Frances Jones Countess Scarborough (age 23) by marriage Countess Scarborough.

On 15 Apr 1703 Charles Hope 1st Earl Hopetoun (age 22) was created 1st Earl Hopetoun by Queen Anne of England Scotland and Ireland (age 38) in recognitions of his father having given up his seat in a lifeboat to the Duke of York during the Sinking of the Gloucester; his father subsequently drowned.

On 15 Apr 1723 Lepell Hervey Baroness Mulgrave was born to John Hervey 2nd Baron Hervey (age 26) and Mary Lepell Baroness Hervey (age 23).

On 15 Apr 1732 Susanna Hoare Countess Ailesbury was born to Henry Hoare "The Magnificient" (age 26) and Susan Colt.

On 15 Apr 1822 Percy Egerton Herbert was born to Edward Herbert 2nd Earl Powis (age 37) and Lucy Graham Countess Powis (age 28) at Powis Castle.

On 07 Apr 1854 Catherine Louise Georgina Marlay (age 23) died from childbirth three weeks after giving birth to her daughter Edith Katherine Manners (deceased) who had died at twelve days old. She was buried at Highgate Cemetery on 15 Apr 1854. Monument by William Calder Marshall (age 41) erected in 1862 in a chapel at St Katherine's Church, Rowsley [Map] built for the purpose.

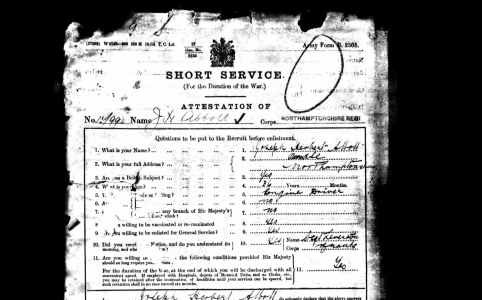

On 15 Apr 1915 Joseph Herbert Abbott (age 38) enlisted in the Northamptonshire Regiment. He is described as 36 years old, and an engine driver.

Joseph Herbert Abbott: In 1877 he was born to Thomas Abbott and Jane Ginn at Polebrook, Northamptonshire. On 11 Nov 1918 he died of sickness.

On 15 Apr 1969 Victoria Eugénie Mountbatten Queen Consort Spain (age 81) died.

Births on the 15th April

On 15 Apr 1282 Frederick "Fighter" Metz IV Duke Lorraine was born to Theobald Metz II Duke Lorraine (age 19) and Isabelle Lady Rumigny Duchess Lorraine.

Before 15 Apr 1303 Catherine Valois was born to Charles Valois I Count Valois (age 33) and Catherine Courtenay Countess Valois (age 28).

On 15 Apr 1367 King Henry IV of England was born to John of Gaunt 1st Duke Lancaster (age 27) and Blanche Plantagenet Duchess Lancaster (age 22) at Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire [Map]. He a grandson of King Edward III of England.

On 15 Apr 1479 Joanna Trastámara Queen Consort Naples was born to Ferdinand I King Naples (age 55) and Joanna of Aragon Queen Consort Naples (age 25). Coefficient of inbreeding 7.30%.

On 28 Mar 1578 Thomas Chicheley of Wimpole was born to Thomas Chicheley of Wimpole and Anne Bourne. He was baptised 15 Apr 1578.

On 15 Apr 1608 John Huddlestone was born.

On 15 Apr 1641 Robert Sibbald was born.

On 15 Apr 1646 Christian V King Denmark and Norway was born to Frederick III King Denmark (age 37) and Sophie Amalie Hanover Queen Consort Denmark (age 18).

On 15 Apr 1668 Nicholas Barnewall 3rd Viscount Barnewall was born to Henry Barnewall 2nd Viscount Barnewall and Mary Nugent Viscountess Barnewall (age 20).

On 15 Apr 1677 Barbara Coningsby was born to Thomas Coningsby 1st Earl Coningsby (age 20) and Barbara Gorges (age 20).

On 15 Apr 1690 John Wallop 1st Earl Portsmouth was born to John Wallop of Farleigh Wallop (age 30) and Alicia Borlase.

On 15 Apr 1699 Susan Murray was born to John Murray 1st Duke Atholl (age 39) and Catherine Hamilton Duchess Atholl (age 37).

On 15 Apr 1715 James Annesley was born to Arthur Annesley 4th Baron Altham (age 26) and Mary Sheffield Baroness Altham (age 23) at Dunmaine. At some time after his birth his father threw his mother out of the house apparently for infidelity. His father also rejected James who, thereafter, was homeless.

On 15 Apr 1723 James Tuchet 7th Earl Castlehaven was born to James Tuchet 6th Earl Castlehaven and Elizabeth Arundell Countess Castlehaven (age 30).

On 15 Apr 1723 Lepell Hervey Baroness Mulgrave was born to John Hervey 2nd Baron Hervey (age 26) and Mary Lepell Baroness Hervey (age 23).

On 15 Apr 1732 Susanna Hoare Countess Ailesbury was born to Henry Hoare "The Magnificient" (age 26) and Susan Colt.

On 15 Apr 1772 Francis Charteris 8th Earl of Wemyss Douglas 4th Earl March was born to Francis Wemyss Douglas (age 23).

On 15 Apr 1787 Henry St John-Mildmay 4th Baronet was born to Henry Paulet St John-Mildmay 3rd Baronet (age 22) and Jane Mildmay.

On 15 Apr 1795 Harriet Molyneux Lady Phillipps was born to General Thomas Molyneau 5th Baronet (age 28) and Elizabeth Perrin Lady Molyneux (age 26).

On 15 Apr 1801 Raikes Currie was born.

On 06 Mar 1804 James Watts of Manchester was born to John Watts and Elizabeth Beesley (age 41). He was baptised on 15 Apr 1804 at St Thomas' Church, Ardwick.

On 15 Apr 1805 Anna Frances Esther Stapleton was born to Thomas Stapleton 12th Baron Despencer (age 38) and Elizabeth Eliot Baroness Despencer (age 47).

On 15 Apr 1807 Reverend James Francis Egerton-Warburton was born to Rowland Egerton-Warburton (age 29).

On 15 Apr 1808 Francis William Topham was born.

On 15 Apr 1809 Dean Thomas Garnier was born to Thomas Garnier (age 33).

On 15 Apr 1811 Mary Marsham was born to Charles Marsham 2nd Earl Romney (age 33) and Sophia Pitt Countess Romney.

On 15 Apr 1822 Percy Egerton Herbert was born to Edward Herbert 2nd Earl Powis (age 37) and Lucy Graham Countess Powis (age 28) at Powis Castle.

On 15 Apr 1822 Frances Anne Emily Vane Duchess of Marlborough was born to Charles William Vane 3rd Marquess Londonderry (age 44) and Frances Vane Tempest Marchioness Londonderry (age 22).

On 15 Apr 1827 Caroline Leveson-Gower Duchess Leinster was born to George Sutherland Leveson-Gower 2nd Duke Sutherland (age 40) and Harriet Elizabeth Georgiana Howard Duchess Sutherland (age 20). Coefficient of inbreeding 3.22%.

On 15 Apr 1832 William Keppel 7th Earl Albermarle was born to George Thomas Keppel 6th Earl Albermarle (age 32).

On 15 Apr 1836 Captain George Fitzclarence was born to George Fitzclarence 1st Earl Munster (age 42) and Mary Wyndham Countess Munster (age 43). He a grandson of King William IV of the United Kingdom.

On 15 Apr 1839 John George Frederick Hope-Wallace was born to James Hope-Wallace (age 31) and Mary Frances Nugent (age 28).

On 15 Apr 1840 William Amelius Aubrey Beauclerk 10th Duke St Albans was born to William Beauclerk 9th Duke St Albans (age 39) and Elizabeth Catherine Gubbins Duchess St Albans (age 22).

On 15 Apr 1843 Edward John Hanmer 5th Baronet was born to Wyndham Hamner 4th Baronet (age 33).

On 15 Apr 1857 John William Honywood 8th Baronet was born to Courtenay Honywood 7th Baronet (age 22).

On 15 Apr 1880 Eleanor Thornton was born to Frederick Thornton Telegraph Engineer at 18 Cottage Grove Stockwell.

On 15 Apr 1881 Gervas Pierrepont 6th Earl Manvers was born to Evelyn Henry Pierrepont (age 25).

On 15 Apr 1885 Ralph Charles Bingham was born to Major-General Cecil Edward Bingham (age 23).

On 15 Apr 1887 Violet Asquith was born to Herbert Henry Asquith 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (age 34) and Helen Kelsall Melland (age 33).

On 15 Apr 1887 Evelyn Maud Keppel Countess Lichfield was born to Edward George Keppel (age 39).

On 15 Apr 1887 Roundell Palmer 3rd Earl Selborne was born to William Palmer 2nd Earl Selborne (age 27) and Beatrix Maud Gascoyne-Cecil Countess Selborne (age 29).

On 15 Apr 1889 Reginald Frankland Payne-Gallwey 5th Baronet was born to Wyndham Harry Payne-Gallwey (age 33).

On 15 Apr 1891 William Joshua Rowley 6th Baronet was born to George Charles Erskine Rowley 3rd Baronet (age 46).

On 15 Apr 1897 Blanche Linnie Fitzroy Countess St Germans was born to Henry Adelbert Wellington Fitzroy 9th Duke Beaufort (age 49) and Louise Emily Harford 9th Duchess Beaufort (age 32).

On 15 Apr 1898 Gerard Foley 7th Baron Foley was born to Henry St George Foley (age 31) and Mary Adelaide Agar (age 28).

On 15 Apr 1913 Margaret Lane-Fox was born to George Lane-Fox 1st Baron Bingley (age 42) and Mary Agnes Emily Wood Baroness Bingley (age 36).

On 15 Apr 1927 Sacheverell Reresby Sitwell 7th Baronet was born to Sacheverell Reresby Sitwell 6th Baronet (age 29) and Georgia Doble (age 21).

On 15 Apr 1937 Conrad Russell 5th Earl Russell was born to Bertrand Russell 3rd Earl Russell (age 64).

On 15 Apr 1951 Claire Anabel Margaret Kerr was born to Peter Francis Walter Kerr 12th Marquess Lothian (age 28).

Marriages on the 15th April

On 15 Apr 1547 William Murray of Tullibardine (age 12) and Agnes Graham were married. She the daughter of William Graham 2nd Earl Montrose (age 55) and Janet Keith Countess Montrose.

On 15 Apr 1548 Thomas Smith (age 34) and Elizabeth Carkeke were married.

On 15 Apr 1650 Anthony Ashley-Cooper 1st Earl Shaftesbury (age 28) and Frances Cecil (age 17) were married. She the daughter of David Cecil 3rd Earl Exeter and Elizabeth Egerton Countess Exeter. She a great x 5 granddaughter of King Henry VII of England and Ireland.

On 15 Apr 1680 Bryan Stapylton 2nd Baronet (age 22) and Anne Kaye Lady Stapylton were married. She by marriage Lady Stapylton Stapleton of Myton in Yorkshire.

Before 15 Apr 1690 John Wallop of Farleigh Wallop (age 30) and Alicia Borlase were married.

Before 15 Apr 1715 Arthur Annesley 4th Baron Altham (age 26) and Mary Sheffield Baroness Altham (age 23) were married. She by marriage Baroness Altham. She the daughter of John Sheffield 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby (age 67) and Ursula Stawell Countess Mulgrave and Conway.

On 15 Apr 1759 John Evans 5th Baron Carbery (age 21) and Emilia Crowe Baroness Carbery were married. They were first cousin once removed.

On 15 Apr 1778 William Strickland 6th Baronet (age 25) and Henrietta Cholmley Lady Strickland (age 17) were married.

On 15 Apr 1799 Charles Lockhart-Ross 7th Baronet (age 36) and Mary Rebecca Fitzgerald (age 21) were married. She the daughter of William Robert Fitzgerald 2nd Duke Leinster (age 50) and Emilia St George Duchess Leinster. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 15 Apr 1805 Barnard Bowes Foord-Bowes (age 35) and Catherine Maria Johnson (age 19) were married. There was no issue from the marriage.

On 15 Apr 1822 Pownoll Bastard Pellew 2nd Viscount Exmouth (age 35) and Georgiana Janet Dick Viscountess Pellew (age 22) were married.

On 15 Apr 1833 Samuel John Brooke-Pechell 3rd Baronet (age 47) and Julia Maria Petre Lady Brooke-Pechell (age 43) were married at her mother's (age 63) house in Grosvenor Square, Belgravia. She by marriage Lady Brooke-Pechell of Paglesham in Essex. She a great x 3 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 15 Apr 1847 Poulett George Henry Somerset (age 24) and Barbara Augusta Norah Mytton (age 24) were married.

On 15 Apr 1847 Henry Vivian 1st Baron Swansea (age 25) and Jessie Dalrymple Goddard (age 22) were married.

On 15 Apr 1857 Walter Long of Rood Ashton in Wiltshire and Mary Ann Hillyar were married.

On 15 Apr 1858 Arthur Edwin Hill aka Hill-Trevor 1st Baron Trevor (age 38) and Mary Catherine Curzon Baroness Trevor (age 20) were married. He the son of Arthur Blundell Sandys Trumbull Hill 3rd Marquess Downshire and Maria Windsor Marchioness Downshire.

On 15 Apr 1874 Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (age 25) and Jenny Jerome (age 20) were married at British Embassy, Paris. Regarded by some as the original Dollar Princess although there are much earlier examples. He the son of John Winston Spencer-Churchill 7th Duke of Marlborough (age 51) and Frances Anne Emily Vane Duchess of Marlborough (age 52).

On 15 Apr 1909 Albert Archibald Primrose 6th Earl Rosebery 2nd Earl Midlothian (age 27) and Dorothy Grosvenor (age 18) were married. He the son of Archibald Philip Primrose 5th Earl Rosebery 1st Earl Midlothian (age 61) and Hannah Rothschild Countess Camden. She a great x 2 granddaughter of King William IV of the United Kingdom.

On 15 Apr 1936 Lieutenant-Colonel Harry Rumbold Bathurst Norman and Ann Prunella Beckett (age 28) were married.

Deaths on the 15th April

On 15 Apr 1053 Godwin Godwinson 1st Earl Kent and Wessex (age 52) died. His son Leofwine Godwinson 2nd Earl Kent (age 18) succeeded 2nd Earl Kent.

On 15 Apr 1136 Richard de Clare was killed. His son Gilbert de Clare 1st Earl Hertford (age 21) succeeded 4th Lord Tonbridge.

On 15 Apr 1216 William Boclande (age 61) died.

On 15 Apr 1237 Bishop Richard Poore died.

Around 15 Apr 1317 Robert Fitzralph (age 41) died.

On 15 Apr 1322 Idonea Leybourne Baroness Say (age 41) died at Leybourne Manor, Malling, Kent.

On 15 Apr 1368 Charles Artois (age 9) died.

On 15 Apr 1389 William Wittelsbach I Duke Lower Bavaria (age 58) died.

On 15 Apr 1393 Elizabeth Pomerania Holy Roman Empress Luxemburg (age 46) died.

Around 15 Apr 1404 Thomas Gorges (age 32) died.

On 12 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho was arrested at Keyford, Somerset and taken to Bath, Somerset [Map]. George York 1st Duke of Clarence (age 27) believed she had murdered his wife Isabel Neville Duchess Clarence who had died four months before.

On 13 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho taken to Cirencester, Gloucestershire [Map].

On 15 Apr 1477 Ankarette Hawkeston aka Twynyho and John Thursby were hanged at Myton Gallows, Warwick [Map].

On 15 Apr 1489 Thomas Witham (age 69) died.

On 15 Apr 1513 Mary Fenwick Lady Millom died at Millom, Cumberland.

On 15 Apr 1517 Katherine Neville (age 74) died.

On 15 Apr 1545 John Gostwick (age 65) died. He was buried at St Michael's Church, Willington.

On 15 Apr 1549 Christine of Saxony (age 43) died.

On 15 Apr 1559 Robert Strode (age 59) died.

On 15 Apr 1570 Bishop William Alley (age 60) died.

On 15 Apr 1573 Henry Long (age 31) died.

On 09 Mar 1589 Frances Sidney Countess Sussex (age 58) died. On 15 Apr 1589 she was buried in Chapel of St Paul, Westminster Abbey [Map].

On 15 Apr 1592 John Chetwynd of Ingestre, Staffordshire (age 66) died.

On 15 Apr 1592 Jane Arundell (age 55) died.

On 15 Apr 1597 William Shelley (age 59) died.

On 15 Apr 1628 Margaret Babthorpe (age 70) died.

On 15 Apr 1632 George Calvert 1st Baron Baltimore (age 52) died. His son Cecil Calvert 2nd Baron Baltimore (age 26) succeeded 2nd Baron Baltimore of Longford in Leinster. Ann Arundell Baroness Baltimore (age 16) by marriage Baroness Baltimore of Longford in Leinster.

On 15 Apr 1633 Colin Mackenzie 1st Earl Seaforth died.

Around 15 Apr 1655 Gervase Scrope (age 61) died.

Before 15 Apr 1665 Samuel Tryon 2nd Baronet (age 47) died. His son Samuel Tryon 3rd Baronet (age 24) succeeded 3rd Baronet Tryon of Layer Marney in Essex.

On 15 Apr 1676 William Cartwright of Aynho Northamptonshire (age 42) died.

On 15 Apr 1682 Thomas Craven (age 71) died.

On 15 Apr 1683 Clement Fisher 2nd Baronet (age 70) died. His nephew Clement Fisher 3rd Baronet (age 8) succeeded 3rd Baronet Fisher of Packington Magna.

Around 15 Apr 1686 Joseph Ashe 1st Baronet (age 68) died.

On 15 Apr 1688 John Northcote (age 59) died.

On 15 Apr 1706 Francis Anderson (age 60) died.

On 15 Apr 1715 Mary Mildmay (age 78) died.

On 15 Apr 1716 Anne Churchill Countess Sunderland (age 33) died.

On 15 Apr 1721 Thomas Domvile 1st Baronet (age 66) died. His son Compton Domvile 2nd Baronet (age 25) succeeded 2nd Baronet Domvile of Templeogue.

On 15 Apr 1723 Alice Wyndham Lady Knatchbull (age 47) died.

Before 15 Apr 1725 Dorothy Stacy died. On 15 Apr 1725 she was buried in Chapel of St John the Baptist, Westminster Abbey [Map].

On 15 Apr 1727 George Compton 4th Earl of Northampton (age 62) died. His son James Compton 5th Earl of Northampton (age 39) succeeded 5th Earl of Northampton. Elizabeth Shirley Countess Northampton (age 32) by marriage Countess of Northampton.

On 15 Apr 1736 Henrietta Douglas Lady Grierson (age 79) died at Turnpike House in Dumfries.

On 15 Apr 1739 Edward Carteret (age 68) died.

On 15 Apr 1740 Charles Downing (age 80) died.

On or before 15 Apr 1750 Evelyn Alston 5th Baronet (age 57) died. His son Evelyn Alston 6th Baronet (age 29) succeeded 6th Baronet Alston of Chelsea. He was buried 15 Apr 1750 at Reigate, Surrey [Map].

On 15 Apr 1750 Catherine Conduit died. She was buried at Westminster Abbey [Map].

On 15 Apr 1761 Archibald Campbell 3rd Duke Argyll (age 78) died. His first cousin John Campbell 4th Duke Argyll (age 68) succeeded 4th Duke Argyll.

On 15 Apr 1762 Edward Dering 5th Baronet (age 57) died. He was buried at St Nicholas' Church, Pluckley on 22 Apr 1762. His son Edward Dering 6th Baronet (age 29) succeeded 6th Baronet Dering of Surrenden Dering in Kent.

On 15 Apr 1764 Jeanne Poisson "Madame de Pompadour" Marquise de Pompadour (age 42) died.

On 15 Apr 1765 Élisabeth Alexandrine Bourbon Condé (age 59) died.

On 15 Apr 1774 Somerset Butler 1st Earl Carrick (age 55) died.

On 15 Apr 1787 William Boothby 4th Baronet (age 65) died unmarried. His first cousin once removed Brooke Boothby 5th Baronet (age 76) succeeded 5th Baronet Boothby of Broadlow Ash in Derbyshire. Phoebe Hollins Lady Boothby (age 70) by marriage Lady Boothby of Broadlow Ash in Derbyshire.

Mary Thorpe 14th Baroness Cobham (age 70) de jure 14th Baroness Cobham although the title remained subject to an attainder so she couldn't claim it.

On 15 Apr 1802 James Whorwood Adeane (age 62) died.

On 15 Apr 1805 George Carpenter 2nd Earl Tyrconnel (age 55) died. His nephew George Carpenter 3rd Earl Tyrconnel (age 17) succeeded 3rd Earl Tyrconnel, 5th Baron Carpenter of Killaghy in County Tipperary.

On 15 Apr 1807 Thomas Fane (age 46) died.

On 15 Apr 1811 Thomas Kingscote (age 53) died.

On 15 Apr 1819 Webb John Seymour (age 42) died.

On 15 Apr 1824 Edward Buller 1st Baronet (age 59) died. Baronet Buller of Trennant Park in Cornwall extinct.

On 15 Apr 1827 George Fludyer (age 65) died.

On 15 Apr 1828 Caroline Stolberg Gedern Duchess Veragua Duchess Berwick (age 73) died.

On 15 Apr 1846 John Saunders Sebright 7th Baronet (age 78) died. His son Thomas Gage Saunders Sebright 8th Baronet (age 44) succeeded 8th Baronet Sebright of Besford in Worcestershire.

On 15 Apr 1850 John Willoughby Michael Cole (age 5) died.

On 15 Apr 1850 John Edwards 1st Baronet (age 80) died. He had no male heirs so Baronet Edwards of Garth in Montgomeryshire extinct.

On 15 Apr 1852 Wilhemina Frederica Bagot died.

On 07 Apr 1854 Catherine Louise Georgina Marlay (age 23) died from childbirth three weeks after giving birth to her daughter Edith Katherine Manners (deceased) who had died at twelve days old. She was buried at Highgate Cemetery on 15 Apr 1854. Monument by William Calder Marshall (age 41) erected in 1862 in a chapel at St Katherine's Church, Rowsley [Map] built for the purpose.

On 15 Apr 1855 William John Bankes (age 68) died. He was buried at Wimborne Minster, Dorset [Map].

On 15 Apr 1856 George Augustus Frederick Cowper 6th Earl Cowper (age 49) died. His son Francis Thomas Cowper 7th Earl Cowper (age 21) succeeded 7th Earl Cowper, 6th Baron Cowper of Wingham in Kent, 8th Baronet Cowper of Ratling Court in Kent.

On 15 Apr 1860 Reverend Alleyn Fitzherbert (age 45) died.

On 15 Apr 1875 Alfred Hervey (age 58) died.

On 15 Apr 1881 Jane Margaret Mary Douglas died.

On 15 Apr 1883 Grand Duke Frederick Francis II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (age 60) died.

On 15 Apr 1884 Reverend Robert Bickersteth (age 67) died.

On 15 Apr 1890 Elizabeth Charlotte Liddell (age 82) died.

On 15 Apr 1914 Delves Louis Broughton 10th Baronet (age 56) died. His son Major John Delves Broughton 11th Baronet (age 30) succeeded 11th Baronet Broughton of Broughton in Staffordshire.

On 15 Apr 1914 John William Ramsden 5th Baronet (age 82) died. His son John Frecheville Ramsden 6th Baronet (age 37) succeeded 6th Baronet Ramsden of Byram in Yorkshire. Joan Buxton Lady Ramsden (age 33) by marriage Lady Ramsden of Byram in Yorkshire.

On 15 Apr 1915 Roland James Corbet 5th Baronet (age 22) was killed in action. His uncle Gerald Vincent Corbet 6th Baronet (age 47) succeeded 6th Baronet Corbet of Moreton Corbet in Shropshire.

On 15 Apr 1925 Florence Hamilton Davis Countess Howe (age 55) died.

On 15 Apr 1928 Rupert Teck (age 20) died.

On 15 Apr 1943 Louisa Hazel Agnew Viscountess Combermere (age 51) died.

On 15 Apr 1957 Alexandra Viktoria Auguste Leopoldine Glücksburg (age 69) died.

On 15 Apr 1969 Victoria Eugénie Mountbatten Queen Consort Spain (age 81) died.

On 15 Apr 1971 Evelyn Alice Grey (age 85) died.

On 15 Apr 1973 John Grimston 6th Earl of Verulam (age 60) died. His son John Grimston 7th Earl of Verulam (age 21) succeeded 7th Earl Verulam, 7th Viscount Grimston, 10th Viscount Grimston, 7th Baron Verulam of Gormanbury in Hertfordshire, 14th Baronet Grimston of Little Waltham in Essex.

On 15 Apr 1974 Princess Irene Glücksburg (age 70) died.

On 15 Apr 1982 Arthur Lowe (age 66) died.

On 15 Apr 2006 Jago Eliot (age 40) died.

On 15 Apr 2014 Gilbert Simon Heathcote 9th Baronet died. His son Mark Simon Robert Heathcote 10th Baronet (age 73) succeeded 10th Baronet Heathcote of London

On 15 Apr 2020 Elizabeth Lumley Baroness Grimthorpe (age 94) died.