On this Day in History ... 21st April

21 Apr is in April.

Events on the 21st April

On 21 Apr 1073 Pope Alexander II (age 63) died.

On 21 Apr 1132 Sancho "Wise" King Navarre was born to García "Restorer" IV King Navarre (age 20) and Marguerite Aigle Queen Consort Navarre.

On 21 Apr 1358 Isabella of France Queen Consort England (age 63) attended the St Georges Day Celebrations (1358) wearing a dress made of silk, silver, 300 rubies, 1800 pearls and a circlet of gold.

Calendars. 21 Apr 1457. Westminster. Grant to Richard, duke of York (age 45), in recompense of the offices of constable of the castles of Carmerdyn, Abbrestwyth and Caerkeny, his estate wherein at the king's desire he has granted to the king’s brother, Jasper, earl of Pembroke (age 25), of 40l yearly at the Receipt of the Exchequer at Westminster by the hands of the treasurer and chamberlains, until he have for life other recompense of the yearly value of 40l. or more. [Fodera.] By K. ete.

On 21 Apr 1509 King Henry VII of England and Ireland (age 52) died of tuberculosis at Richmond Palace [Map]. His son Henry VIII (age 17) succeeded VIII King England. Duke York and Earl Chester merged with the Crown.

Wriothesley's Chronicle 1485-1509. 21 Apr 1509. This yeare, in Aprill, died King Henry the Vllth (age 52) at Richmond [Map] and his Sonne King Henry the VIII (age 17) was proclaymed Kinge on St Georges dayeg 1508 [1509], in the same moneth.

Note g. We should here read St George's Eve, 22nd April, 1509, from which day Henry Vlll reckoned his regnal years. Stow, however, says that Henry was not proclaimed till the 24th.

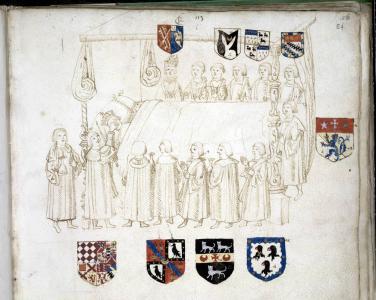

After 21 Apr 1509 Thomas Wriothesley (age 21), who wasn't present, made a drawing of the death of Henry VII (deceased). The drawing shows those present and in some cases provides their arms by which they can be identified. From top left clockwise:

After 21 Apr 1509 Thomas Wriothesley (age 21), who wasn't present, made a drawing of the death of Henry VII (deceased). The drawing shows those present and in some cases provides their arms by which they can be identified. From top left clockwise:

Bishop Richard Foxe (age 61).

Two tonsured clerics.

George Hastings 1st Earl Huntingdon (age 22).

Richard Weston of Sutton Place (age 44).

Richard Clement of Ightham Mote (age 27).

Matthew Baker Governor of Jersey.

John Sharpe of Coggleshall in Essex.

Physician holding urine bottle.

William Tyler.

Hugh Denys.

William Fitzwilliam 1st Earl of Southampton (age 19) closing the King's eyes. There is doubt as to whether the person shown is William Fitzwilliam 1st Earl of Southampton (age 19) given his age of around nineteen at the King's death. He appears to be holding a Staff of Office although sources state he wasn't appointed Gentleman Usher, in which role he would have a Staff of Office, until Henry VIII's Coronation in Jun 1509.

The Arms below him are Quarterly 1 Lozengy argent & gules (FitzWilliam); 2 Arms of John Neville 1st Marquess Montagu 3 Quartered 1 possibly Plantagenet with white border ie Holland 2&3 Tibetot, 4 Unknown, overall a star for difference indicating third son. William Fitzwilliam 1st Earl of Southampton (age 19) was his father's third son, and his mother was Lucy Neville (age 41) daughter of John Neville 1st Marquess Montagu. It appears correct that the person represented is William Fitzwilliam 1st Earl of Southampton (age 19). William Fitzwilliam 1st Earl of Southampton (age 19) was the childhood companion of Henry VIII (age 17).

Physician holding urine bottle.

Richard Weston of Sutton Place: he and Anne Sandys were married. In 1465 he was born. In 1541 he died.

Matthew Baker Governor of Jersey: From 1486 he was appointed Governor of Jersey. In May 1513 he died in Bermondsey Abbey.

Letters and Papers 1533. 21 Apr 1533. Add. MS. 28,585, f. 236. B. M. 365. Count Of Cifuentes to Charles V.

Received his letter of April 8, at Vulsena. Entered Rome on Thursday 17th. Had an audience of the Pope on Saturday. He told me he had heard that the English ambassadors and other persons on the King's behalf had urged him to revoke the brief sent for the separation of the King and "La Anna (age 32);" which he would not do, out of respect to the Emperor, though there are errors in the brief which would justify it. He has remitted it to the cardinals De Monte and Campeggio, the auditors Capisucha and Simoneta, and the Datary. Said I was not a lawyer, but I did not think the Pope ought to hear any one on the King's part, as they showed no power; they only wish to protract the case, and give the King an opportunity of marrying, which he has promised the Lady to do before St. John's Day. His Holiness said he believed this, as he had the same news from France, and that the reason was the Lady's pregnancy. He said also, if the marriage took place, the remedy of the case remained. Replied that he should do justice at once, as the Queen thought so much of it; that although the King spoke those words he would not do it if the Pope decided the case, but the delay they see here gives them occasion to say such words, and may lead them to do it in deed. He replied that he would do justice, and order it to be done, and asked what the Emperor would do if this marriage took place. Said your Majesty would act as became a powerful and wise prince. He finished the conversation by saying he would do justice.

Rome, 21 April 1533.

Sp., pp. 6. Modern copy.

Letters 1536. 21 Apr 1536. Vienna Archives. 699. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

On coming to Court I was most cordially received by all the Lords of the Council, who congratulated me on the happy news, praising greatly the good service they presumed that I had done,—especially Lord Rochford (age 33), the Concubine's (age 35) brother, to whom I said that I did not doubt that he had as great pleasure in what was taking place as any other, and that he would assist as in a matter for the benefit of the whole world, but especially of himself and his friends. He showed me "fort grosse chiere," and I dissembled in the same way with him, avoiding all occasions of entering into Lutheran discussions, from which he could not refrain.

Before the King went out to mass Cromwell came to me on his part to ask if I would not go and visit and kiss the Concubine (age 35), which would be doing a pleasure to this King; nevertheless, he left it to me. I told him that for a long time my will had been slave to that of the King, and that to serve him it was enough to command me; but that I thought, for several reasons, which I would tell the King another time, such a visit would not be advisable, and I begged Cromwell to excuse it, and dissuade the said visit in order not to spoil matters. Immediately afterwards Cromwell came to tell me that the King had taken it all in good part, hoping that hereafter "lon y supplyeroit assez," and he immediately added that after dinner I should speak with the King at leisure, and that on leaving him, agreeably to their custom, I ought to see those of the Council and explain my charge. I told him that I thought things were so honorable and reasonable, and had been foreseen so long, that I thought the King would make up his mind immediately; and if not, he to whom my credence was addressed would make a far better report to the Council than I could; nevertheless, that till I had heard part of the King's will, I could neither promise to go, nor not to go, to the said Council, though I meant to speak particularly to all, and do all that they would counsel me. Just after this the King came out and gave me a very kind reception, holding for some time his bonnet in his hand, and not allowing me to be uncovered longer than himself; and after asking how I was, and telling me that I was very welcome, he inquired of the good health of your Majesty and showed himself very glad to hear good news. He then asked where you were, and on my telling him that the courier had left you near Rome, he said that by the date of your Majesty's letters to his Secretary it appeared that you were at Gaeta when the courier left. Hereupon he asked if you would stay long at Rome, and on my telling him that I thought not, unless your Majesty could gratify him by a long delay, for which purpose I was sure you would make no difficulty either in remaining or doing anything else that you could on his account, he said he thought it would have been better for your interests not to have come so soon to Rome, but to have staid in Naples, so as to afford a bait to those who needed it to involve themselves further in the meshes. I said that there was still time enough to use such dissimulation, and that I was sure you would in this and other matters be glad to follow his counsel as that of a very old friend, good brother, and, as it were, a father, as he might understand by what I should tell him hereafter more at leisure. On this he said, Well, we should have leisure to discuss all matters. I was conducted to mass by Lord Rochford (age 33), the concubine's brother, and when the King came to the offering there was a great concourse of people partly to see how the concubine and I behaved to each other. She was courteous enough, for when I was behind the door by which she entered, she returned, merely to do me reverence as I did to her. After mass the King went to dine at the concubine's lodging, whither everybody accompanied him except myself, who was conducted by Rochford (age 33) to the King's Chamber of Presence, and dined there with all the principal men of the Court. I am told the concubine (age 35) asked the King why I did not enter there as the other ambassadors did, and the King replied that it was not without good reason. Nevertheless, I am told by one who heard her, the said concubine after dinner said that it was a great shame in the king of France to treat his uncle, the duke of Savoy, as he did, and to make war against Milan so as to break the enterprise against the Turks; and that it really seemed that the king of France, weary of his life on account of his illnesses, wished by war to put an end to his days. As soon as the King had dined, he, in passing by where I was, made me the same caress as in the morning, and, taking me by the hand, led me into his chamber, whither only the Chancellor and Cromwell followed. He took me apart to a window. I reminded him of several conversations which Cromwell and I had had, and also of those of your ambassador in France with Wallop, and also of the old affection your Majesty had borne him, and began to declare your will touching the four points, taking the utmost care to speak as gently as possible, that he might not find grounds of quarrel or irritation. He heard me patiently and without interruption, till at last, on my saying that your Majesty, desirous above all things of the peace of Christendom, had forborne your claim to Burgundy, which you might demand by a much better title than the invaders of Savoy and Milan, he answered that Milan belonged to the king of France, and the duchy of Burgundy also, for you had renounced it by the treaty of Cambray, which qualified the unreasonable conditions of that of Madrid, and that even if Milan had now come to your hands the defensive treaties comprehended only the lordships possessed at the time they were passed. I showed him, but not without difficulty, that he was illinformed about your rights to Milan and Burgundy, and also that when those treaties were made you were the lawful Lord of Milan, and he who held it was only feudatory, after whose death the duchy was not newly acquired by your Majesty, but had only been consolidated; which argument, as Cromwell informs me, has since been weighed and approved by the King and his Council.

Letters 1536. 21 Apr 1536. Vienna Archives. 699. Chapuys (age 46) to Charles V.

Perceiving by this conversation that the King's affection was not sincere, I did not enter further into business, but only asked him if the king of France were to break or attempt to break any other article touching the duke of Gueldres or other matters, whether he would not aid your Majesty according to the treaties. He replied that, so far as he found himself bound, he would acquit himself better than several others had done towards him; and as to the rest, in which he was not bound, he would give satisfaction as occasion was given to him. Returning to the subject of the war against the duke of Savoy, he wished me to understand, notwithstanding that I had told him what you had written to me, that the said war was not against the will of your Majesty, and also that the duke of Savoy had lately offered to come to the court of France, "sur quoy ne resta a luy donner assez raisons a lopposite." After this he called the Chancellor and Cromwell, and made me repeat before them what I had said to him, which I did succinctly, without interruption from him or the others. After which they talked together, while I conversed and made some acquaintance with the brother (age 36) of the young lady [Jane Seymour (age 27)] to whom the King is now attached, always keeping an eye upon the gestures of the King and those with him. There seemed to be some dispute and considerable anger, as I thought, between the King and Cromwell; and after a considerable time Cromwell grumbling (recomplant (?) et grondissant) left the conference in the window where the King was, excusing himself that he was so very thirsty (altere) that he was quite exhausted, as he really was with pure vexation (de pur enuyt), and sat down upon a coffer out of sight of the King, where he sent for something to drink. Shortly afterwards the King came out of the conclave, I know not whether to come near me, or to see where Cromwell was. He told me that the matters proposed were so important that without having my propositions in writing he could not communicate them to his Council or make me any reply. I told him that I was not forbidden to do so, but I could not venture, for several reasons, and I thought it a new thing, seeing that hitherto he had not asked anything of me by way of writing, and had never found me variable or vacillating, either now or before, and that I had learned from his ambassadors whom he sent to Bologna to your Majesty to make such refusal, although they had not such good reason for it as I; also I had taken example of Cromwell, who had never given me anything in writing; and if he wished such writing to be assured that there was no dissimulation on your Majesty's part, I would offer my ears, which I would give far more unwillingly than all the writings in the world, if there should be any deceit on the side of your Majesty;—with which conversation, as Cromwell told me afterwards, the King was far better assured than before, taking this offer in good part. Nevertheless, he insisted wonderfully on having the said writing, and said several times very obstinately that he would give no reply. Nevertheless, he did reply, confusedly and in anger, to the following effect:—(1.) The affair of the Pope did not concern your Majesty, if you did not wish to meddle with it to vindicate your authority over the whole world, and if he wished to treat with His Holiness he has means and friends without needing your intercession. (2.) Concerning the Princess she was his daughter, and he would treat her according as she obeyed him or not, and no one else had a right to interfere. (3.) As to the subvention against the Turk, it was necessary first to re-establish old friendship before putting people to expense. (4.) As to the fourth, which was most urgent, and which I have chiefly pressed, he said he would not violate any promise he has made, or refuse the friendship of any one who desired it, provided it was such as was becoming, but that he was no longer a child, and that they must not give him the stick, and then caress him, appealing to him and begging him. In saying this, to show how he was experienced in business, he began playing with his fingers on his knees, and doing as if he were calling a child to pacify it, [and said] that before asking an injured person for favor and aid it was necessary to acknowledge old favors. And on my saying that we had been so long treating of this re-establishment, and I had pressed for an overture of what he wished to be done, but to no purpose, he answered that it was not for him to make an overture, but for those who sought him. I replied that if he who was hurt did not show his wound it was impossible to heal it. He then said he wished your Majesty would write to him, [desiring] that if there had been in the past any ingratitude or error on your part towards him, he would forget it, [and] requesting him to show that the root of old amity is not disturbed. I told him this was not reasonable, and he moderated the proposal, suggesting that you should request him not to speak any more of the past. I said no other letter was needed, because I asked it of him in the name of your Majesty; but he persisted that he must have letters, and it was no use reminding him of what he has several times said to me before, that delay is the ruin of all good works.

On 13 May 1600 Anne Spring (deceased) was at St Peter's Church, Tawstock [Map]. On 21 Apr 1614 Thomas Hinson (deceased) was buried with his wife Anne Spring (deceased).

Here lyeth ye bodies of Thomas Hinson Esquire and Anne his wife: this Thomas was borne at Fordham in Cambridgeshire, and was Master of Artes & sometime fellowe of Caius Colledge in Cambridge and tutor there to the right honourable William Earle of Bathe under whome he bore afterwardes divers offices and was untill his death Surveyor & Receaver Generall of all his lands and revenewes & Likewise in Comission of the peace in the Countie of Devon: and dyed the XVIIIth of Aprill 1614.

Anne was the eldest daughter of Sr Willm Springe Knight and Cosyne German to the Earle of Bathe now livinge she had issue by the said Thomas Hinson five sonnes and nyne daughters whereof are surviving VI viz Willm Thomas Margaret Ellinor Elizabeth and Rebekah the said Anne died in the true faith of Christ the seventh of May Ano Doni 1600 .

Anne Spring: Around 1553 she was born to William Spring and Anne Elizabeth Kitson.. Before 07 May 1600 Thomas Hinson and she were married. On 07 May 1600 Anne Spring died.

Thomas Hinson: Around 1551 he was born. Around 1573 Thomas Hinson was tutor to William Bourchier 3rd Earl Bath at Caius College, Cambridge University. On 18 Apr 1614 he died.

On 21 Apr 1603 William Skipwith (age 39) was knighted by King James I of England and Ireland and VI of Scotland (age 36) at Worksop Manor whilst King James was travelling to London following the Union of the Crowns.

In 1665 Henry Brouncker 3rd Viscount Brounckner (age 38) was elected MP New Romney which seat he held until 21 Apr 1668 when he was expelled from the House of Commons when charges were brought against him, for allowing the Dutch fleet to escape during the Battle of Lowestoft, and for ordering the sails of the English fleet to be slackened in the name of the Duke of York (age 31). This was essentially an act of treason. Such a military decision, taken without the Duke's (age 31) authority, was an incident seemingly without parallel, especially as his apparent motive was simply that he was fatigued with the stress and noise of the battle.

On 21 Apr 1696 D'Aubigny Turbeville died. Memorial at Salisbury Cathedral [Map].

On 21 Apr 1761 Godfrey Copley (age 54) died. He was buried at St Mary’s Church, Sprotbrough [Map].

Godfrey Copley: In 1707 he was born to Lionel Copley and Maria Wilson aka Burrill.

On 21 Apr 1775 Edward Smith-Stanley 13th Earl of Derby was born to Edward Smith-Stanley 12th Earl of Derby (age 22) and Elizabeth Hamilton Countess Derby (age 22).

On 21 Apr 1787 Emily Lamb Countess Cowper was born to Penistone Lamb 1st Viscount Melbourne (age 42) and Elizabeth Milbanke Viscountess Melbourne (age 35).

On 21 Apr 1814 Angela Burdett-Coutts 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts was born to Francis Burdett 5th Baronet (age 44) and Sophia Coutts Lady Burdett.

On 21 Apr 1821 George Gammon Adams was born to James Adams at Staines.

On 21 Apr 1829 Anne Hay Mackenzie Duchess Sutherland was born to John Hay Mackenzie of Newhall and Cromarty.

On 21 Apr 1844 Kate Terry was born to Benjamin Terry (age 26).

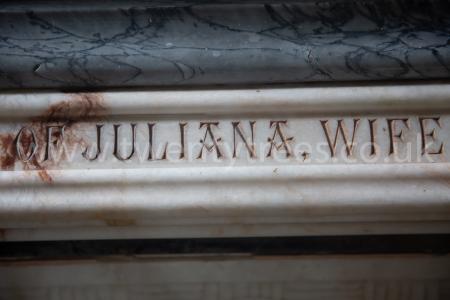

On 21 Apr 1870 Juliana Whitbread Countess Leicester (age 44) died. Memorial at St Withburga's Church, Holkham [Map] sculpted by Joseph Edgar Boehm (age 35).

Juliana Whitbread Countess Leicester:

On 03 Jun 1825 she was born to Samuel Charles Whitbread and Julia Brand.

On 20 Apr 1843 Thomas Coke 2nd Earl of Leicester and she were married. She by marriage Countess of Leicester. He the son of Thomas Coke 1st Earl of Leicester and Anne Amelia Keppel Countess Leicester. He a great x 4 grandson of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland. She a great x 5 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Apr 1875 Henry William Pickersgill (age 92) died.

The Times. 21 Apr 1899. Marriage of Lord Crewe and Lady Peggy Primrose.

The marriage of Lady Margaret (Peggy) Primrose (age 18), younger daughter of the Earl of Rosebery (age 51), with the Earl of Crews (age 41), which took place at Westminster Abbey [Map] yesterday, was remarkable, not only as a brilliant spectacle, bat also on account of the extraordinary degree of public interest which the event evoked, and the testimony thus afforded to the popularity of the late Prime Minister. It was an ideal day for a wedding, the sun shining brilliantly. Parliament Square and the approaches to the Abbey early in the day presented a gay and animated spectacle. An hour or more before the time announced for the opening of the Abbey doors, and a couple of hours before the bridal party were expected, people began to collect in the Abbey precincts, and in a short time great crowds were stretching right away to the railings of the Houses of Parliament. As time wore on and the vast concourse grew into extraordinary dimensions the police on duty had the utmost difficulty in regulating the living mass. Taffic became congested, and the constables in some cases were swept off their feet by the surging and panting multitude, but everywhere the best of good humour seemed to prevail in the streets.

Meanwhile the interior of the Abbey was also the centre of much life and movement. The wedding was fixed for 1:30, aud the doors, at each of which a long queue of ticket-holders and others had long been patiently waiting, were opened three-quarters of an hour earlier. Immediately the throngs, in which the bright costumes of the ladies were conspicuous, wwept into the Abbey. None-ticket holders were admitted by the north door only. This entrance was literally besieged, and a quarter of an hour after it was opened it had to be closed, for in that brief space the northern transept-the porLion of the Abbey allotted to the general public-had become so densely packed that it would not hold another spectator. Those privileged visitors who held permits either for tue nave or the south transept seemed none the less eager to secure advantageous places, for every one came early. Many of the ladies stood upon the seats in their eagerness to obtain a good view. As the guests arrived Sir Frederick Bridge played an appropriate selection of music upon the grand organ.

The rare spectacle of floral decorations in the Abbey attracted general attention. At each end of the alter rails there was a towering palm with a collection of Lilium Harrisii and marguerites grouped at the base, while blooms of Liliam Harrisii also adorned the altar itself. Specimen palms with foliage and flowering plants were placed against the organ screen facing the western entrance, by which the bridal party were shortly to enter.

The arrival of the specially invited guests also proved a source of much interest. These privileged persons, numbering some 500 or 600, friends of the contracting parties and including men distinguished in politics, diplomacy, literature, and art, were escorted to seats in the choir and under the lantern. The Earl of Crewe (age 41), with his best man, the Earl of Chesterfield (age 45), arrived about ten minutes past 1. Each of them wore a marguerite in his buttonhole. They joined the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire under the lantern. The Prince of Wales (age 4) arrived about 25 minutes past 1. His Royal Highness, attended by the Hon. Seymour Fortescue (age 43), was received by Lord Rosebery's sons, Lord Dalmeny (age 17) and the Hon. Neil Primrose (age 16), by whom he was conducted to the Jerusalem Chamber. The Duke of Cambridge (age 80), who quickly followed, attended by Colonel FitzgGeorge, was met at the same door by the Hon. Neil Primrose, under whose escort he joined the Prince of Wales, after which their Royal Highnesses went to the choir and took the seats which had been specially reserved for then.

Among the others present were: The Duchess of Buckingham and Chandos, the Marquis and Marchioness of Breadalbane, the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch. Mr. Balfour M.P., the Duke (age 52) and Duchess (age 46) of Somerset, the Marquis of Lansdowne (age 54), Mr. Asquith, M.P., and Mrs. Asquith, the Austrian Ambassador, the Earl and Countess of Harewood, the Duchess of Cleveland. the Earl of Kirnberley and Lady Constance Wodehouse, Lady Jeune and Miles Stanley, the Marquis of Dufferin, Sir R. Campbell-Bannerman, M.P., and Lady Campbell-Bauneiman, Mr. Bryce, M.P., and Mrs. Biyce, Mr. J. B Balfour, H.P., and Mrs. Balfour, Mir. H Gladstone, the Earl aud Countess of Corck, the Lord Chief Justice (Lord Russell of Killoren) and the Hon. Mliss Russell, Sir H. Fowler, f.P., and Lady Fowler, Earl and Countess De Grey, Mr. Munro-Fergrsca, M.P., and Lady Helen Munro-Ferguison, Sir Henry Irving, ir. Morley, M.P., S,r John and lady Puleston, the Marquig and Marehioness of Ripon, Lord and Lady Recay, Lord and Lady Rothschild, and all the Londoa representatives of the Rothschild family, Sir Charles aild Lady Tennant, Lord Wandsworth. Lord and Baroness Wenlock, Lord Leconfdeld, the Earl of Verulamn, Mr. aud Mrs. George Alexander idiss Mundella, Sir E. Sassoon, H.P., General and Mrs. Wauchope, Sir E. Lawson, Mr. Harmswortl, Sir Lewis Morris. Lord James of Hereford and Miss James the Hon. P. Stanhope, H.P., and Countess Tolstoy, the Earl and Countess of Aberdeen, Mr. Shaw Lefevre, Sir Charles Dalry,uiple MP. Mr. Sydney Buxton, M.P.,hr. George Russell, Tr. G. E. Buckle, Georgina, Countess A! Dudley, Sir Humphrey and Lady De Trafford, Sir Edgar and Lady Helen Vincent, Sir John Lubbock, hLP., and Lady Lubbock, Lord Hamilton of Dalzell' Sir Henry Primrose, Lord and Lady St. Oswald, Eara and Countess Stanbope, Mr. Rochfort Maguire. M.P., and Mrs. Maguire, Lady Emily Peel, Loid E. Pitzmaurice. HI.P., Earl and Countess Carrington, Lord and Lady Bnrgheiere, Loud and Lady Battersea, Lord and Lady Henry Bentnek, Lord and Lady Poltimure, the Earl of Essex, and Viscount Curzon,.p., and Viscountess Ctu-zon.

Note B. the time that the whole of the company bad assembled the transepts and choir were densely packed. The attendants had the greatest difficulty in keeping many of the spectators within the specified bounds, and owing to the crushing and crowding several ladies fainted. At half-past 1 Lord Rosebery arrived with the bride at the western entrance, having had a very heartv reception as they passed through the streets. This cordial greeting was repeated again and again as Lord wRosebery handed his daughter out of the carriage. She appeared relf-possessed and smiled upon those around her. Lady Peggy Primirose was attired in a dress of white satin of the new shape, with a very long train (not separate from the dress as in the old style). It was profusely embroidered with clusters of diamonds designed as primroses. The front of the skirt opened over a petticoat of exquisite point d'Alengon laco, which was formerly tn the possession of Marie Antoinette, and was a present from the bride's aunt, Miss Lucy Cohen. The bodice was embroidered and trimmed with similar lace aud its sleeves were of transparent mausselijt I soic. The veil was of tulle, and in nlace of the nsual coronet of orange blossom the bride wore a smart Louis XVI bow of real orange flowers. Jewelry was scarcely at all employed. Lady Peggy carried a magnificent bouquet composed mainly of orchids, white roses, lilies, and marguerites.

The bride (age 18) was received at the door of the Abbey by her ten bridesmaids. They were Lady Sybil Primrose (age 20), elder sister of the bride; the Ladies Annabel (age 18), Celia (age 15), and Cynthia (age 14) (Crewe-Milnes, daughters of the bridegroom; the Hon. Maud and the Hon. Margaret Wyndham, daughters of Lord Leaconfield; the Hon. Evelina Rothschild, daughter of Lord Rothschild; Miss Louise Wirsch; Lady Juliet Lowther (age 18), daughter of the late Earl of Lonsdale and Countess de Grey; and Miss Muriel White, daughter of Mr. Blenry White, of the United States Embassy. They were all dressed alike, in white embroidered moseline de rois over white silk. The skirts were made with shaped flounces with cream lace insertion, and upon the bodices were fichns edged with lace. The sashes were of primrose chiffon, and the hats of primrose tulle with white ostrich feathers, one side being turned up with Lady de Rothschild roses. The bouquets were of the same roses, tied with long tLreamers of the primrose chiffon. Each of the bridesmaids wore a gold curb bracelet with the initials of the bride and bridegroom in enamel, the gifts of the bridegroom.

The formation of the bridal proession was a very picturesque feature of the ceremonial. Schubert's "Grand March" was played, and the,vast congregation rose to their feet as the choir advanced, followed along the nave by the clergy, after whom caine the bride leaning upon the arm of her father, who wore a bunch of primroses in his coat, and attended by her bridesmaids. All eyes were naturally turned to the bride, but she did not lose her composare during the long and trying walk up the nave to the choir.

The procession approached the choir, Lord Crewe who with his best man had been standing a few yards from the Prince of Wales advanced to meet the bride, and the party ha1ted at a point between the choir and the lantern, where the first part of the wedding service was taken, in full view of the choir stalls, where the principal guests were seated. The hymn "O perfect Love" having been sung, the marriage service began. The officiating clergy were the Rev. Dr. Butler (Master of Tririty), the Dean of Westminster Abbey, Canon Blackburne, vicar of Crewe-green, Crewe, Canon Armitage Robinson, and the Precentor of Westminster. Dr. Butler, who took the principal part of the service, read the words in a very impressive manner. The bride made the responses in a perfectly audible voice. Upon the conclusion of the first part of the ceremony the procession of the clergy and the bride and bridegroom, followed by the bridesmaids, moved towards the east. They passed, while the psalm was sung to a chant by Beethoven, through the sacrarrum to the altar, where the concluding portion of the service was said by the Dean and other clergy. Next came the hymn "Now thank we all otr God," after which the blessing was pronounced and the service was brought to a close, to the actompaniment of a merry peal from the bells of St. Margaret's Church. As the procession moved down the Abbey to the Jerusalem Chamber to sign the register Mendelssohn's "Wedding March" was played, and the great majority of the congreation prepared to take their departure. 'ihs Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge were among those who accompanied the bridal party and their relatives to the Jerusalem Chamber and appended their names to the register. Lord and Baroness Crewe, with their friends, left the Abbey amid a renewal of those enthusiastic demonstrations which had marked Lady Peggy Primrose's arrival as a bride. A reception and luncheon was given at Lord Rosebery's town house attended by the Prince of Wales; the Duke of Cambridge, and about 600 other guests, most of whom had attended the ceremony in theAbbey. Later in the day the Earl and Countess of Crewe left town for Welbeek Abbey,'placed at their disposal by the Duke and Duchess of Portland for the early part of the honeymoon. The bride wore a travelling dress of green cloth, the skirt being stitched with gold, the bodice and sleeves being embroidered in natural colour silk and gold with primroses She vwore a large wzhite hat w,ith feathers to match. THE WEDDING PRES IU& After the departure of the bride and bride-groom the numerous wedding presents displayed at Lord Rosebery's house were inspected with much interest by those of the guests who had not previously seen them.

Soon after 7 o'clock last evening the train conveying Lord and Baroness Crewe arrived at Worksop Station. The platform was thronged with people, who gave a most cordial, though quiet, reception to the newly-married pair. On their arrival at Welbeck Abbey [Map] the visitors were received with every honour, and a bouquet was presented to Baroness Crewe. The employes on the estate of Dalmeny dined together last night in celebration of the marriage of Lady Peggy Primrose. Mr. Drysdale, the chamberlain, presided over a company of about 300. After dinner there was a dance, and a display of fireworks was given in the grounds. The burgh of Queensferry, which adjoins Lord Rosebery's Dalmeny estate, was decorated yesterday in honour of the wedding. A banquet was held in the council chambers, at which the health of the bride and bridegroom was honoured, and a congratulatory telegram forwarded to Baroness Crewe.

On 21 Apr 1917 Henry Molyneux Paget Howard 19th Earl Suffolk 12th Earl Berkshire (age 39) was killed in action when a piece of shrapnel entered his heart. His son Charles Howard 20th Earl of Suffolk, 13th Earl Berkshire (age 11) succeeded 20th Earl Suffolk, 13th Earl Berkshire.

On 21 Apr 1917 Cecil James Parnell (age 18) died. He was buried at All Saints Church, Barnwell [Map]. TR1O/27027, 31st (Training Reserve) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). Died on service in United Kingdom.

Cecil James Parnell: Around 1899 he was born to Pharoah Parnell at Winwick, Huntingdonshire.

On 21 Apr 1926 Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom was born to King George VI of the United Kingdom (age 30) and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon Queen Consort England (age 25).

Births on the 21st April

On 21 Apr 1132 Sancho "Wise" King Navarre was born to García "Restorer" IV King Navarre (age 20) and Marguerite Aigle Queen Consort Navarre.

On 21 Apr 1434 Margaret Peake was born to John Peake at Cople.

On 21 Apr 1539 Unamed Habsburg Spain was born to Charles V Holy Roman Emperor (age 39) and Isabel Aviz Queen Consort Spain (age 35). Coefficient of inbreeding 10.98%.

On 21 Apr 1568 Frederick II Oldenburg was born to Duke Adolph Oldenburg of Holstein-Gotorp (age 42) and Christine Hesse (age 24).

On or before 21 Apr 1612, the date he was baptised, Charles Longueville 12th Baron Grey of Ruthyn was born to Michael Longueville (age 22) and Susan Grey.

On 21 Apr 1620 Henry Winchcombe was born to Henry Winchcombe (age 26).

Before 21 Apr 1629 Francis Villiers was born to George Villiers 1st Duke of Buckingham and Katherine Manners Duchess Buckingham (age 26).

Before 21 Apr 1636 Henry Hare 2nd Baron Coleraine was born to Hugh Hare 1st Baron Coleraine (age 30) and Lucy Montagu Baroness Coleraine (age 26).

On 21 Apr 1665 George Neville 12th and 10th Baron Bergavenny was born to George Neville 11th and 9th Baron Bergavenny (age 50) and Mary Gifford Baroness Bergavenny (age 35).

On 21 Apr 1671 John Law was born.

On 21 Apr 1673 Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick was born to Johann Friedrich Hanover (age 47) and Benedicta Henrietta Palatinate Simmern (age 21). She a great x 2 granddaughter of King James I of England and Ireland and VI of Scotland.

On 21 Apr 1705 Oswald Mosley 2nd Baronet was born to Oswald Mosley 1st Baronet (age 30) and Elizabeth Thornhaugh (age 33).

On 27 Mar 1707 John Tynte 4th Baronet was born to John Tynte 2nd Baronet (age 24) and Jane Kemeys Lady Tynte (age 22). He was baptised on 21 Apr 1707 at the Church of St Edward King and Martyr, Goathurst [Map].

On 21 Apr 1744 John Meade 1st Earl of Clanwilliam was born.

On 21 Apr 1746 James Harris 1st Earl Malmesbury was born to James Harris (age 36) and Elizabeth Clarke and Elizabeth Clarke at Salisbury.

On 21 Apr 1749 Edmund Cradock-Hartopp 1st Baronet was born to Joseph Bunney.

On or before 21 Apr 1756 Thomas Buston was born.

On 21 Apr 1763 Georgiana Anne Poyntz was born to William Poyntz (age 29).

On 21 Apr 1768 Maria Jane Bowes was born to John Lyon 9th Earl Strathmore and Kinghorne (age 30) and Mary Bowes Countess Strathmore (age 19).

On 21 Apr 1775 Edward Smith-Stanley 13th Earl of Derby was born to Edward Smith-Stanley 12th Earl of Derby (age 22) and Elizabeth Hamilton Countess Derby (age 22).

On 21 Apr 1785 Charles Joseph Comte de Flahaut was born.

On 21 Apr 1786 Robert Chaplin was born to Charles Chaplin (age 55).

On 21 Apr 1786 Charles Chaplin was born to Charles Chaplin (age 26) and Elizabeth Taylor.

On 21 Apr 1787 Emily Lamb Countess Cowper was born to Penistone Lamb 1st Viscount Melbourne (age 42) and Elizabeth Milbanke Viscountess Melbourne (age 35).

On 21 Apr 1798 Margaret Harriet Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck was born to William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck 4th Duke Portland (age 29) and Henrietta Scott Duchess Portland (age 24).

On 21 Apr 1799 John Pollard Willoughby 4th Baronet was born to Christopher Willoughby 1st Baronet (age 50) and Martha Evans Lady Willoughby (age 31).

On 21 Apr 1812 Robert Pryor was born to Thomas Marlborough Pryor (age 35) and Hannah Hoare (age 32).

On 21 Apr 1813 John Dick-Lauder of Fountainhall 8th Baronet was born.

On 21 Apr 1814 Angela Burdett-Coutts 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts was born to Francis Burdett 5th Baronet (age 44) and Sophia Coutts Lady Burdett.

On 21 Apr 1821 George Gammon Adams was born to James Adams at Staines.

On 21 Apr 1824 Augusta Anne Somerset Lady Barron was born to Charles Henry Somerset (age 56) and Mary Paulett.

On 21 Apr 1829 Anne Hay Mackenzie Duchess Sutherland was born to John Hay Mackenzie of Newhall and Cromarty.

On 21 Apr 1834 Colonel Richard Talbot Plantagenet Stapleton was born to Francis Jarvis Stapleton 7th Baronet (age 26).

On 21 Apr 1844 Kate Terry was born to Benjamin Terry (age 26).

On 21 Apr 1846 Emily Theresa Stern Baroness Sherborne was born to Hermann Stern.

On 21 Apr 1853 Kenneth Hagar Kemp 12th Baronet was born to Reverend Nunn Robert Pretyman Kemp of Erpingham in Norfolk (age 39) and Mary Harriet Hagar at Erpingham, Norfolk.

On 21 Apr 1855 Jane Evelyn Cole was born to William Willoughby Cole 3rd Earl Enniskillen (age 48) and Jane Casamaijor Countess Enniskillen.

On 21 Apr 1868 Mary Rose Florence Bligh was born to John Stuart Bligh 6th Earl Darnley (age 41) and Harriet Mary Pelham Countess Darnley (age 39).

On 21 Apr 1879 Walter Robert Buchanan Riddell 12th Baronet was born.

On 21 Apr 1884 Henry Moore 10th Earl of Drogheda was born to Ponsonby William Moore 9th Earl of Drogheda (age 37).

On 21 Apr 1887 Alexandra Viktoria Auguste Leopoldine Glücksburg was born to Friedrich Ferdinand Glücksburg Duke Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg (age 31) and Victoria Friederike Oldenburg Duchess Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glücksburg (age 27).

On 21 Apr 1902 Audrey Evelyn James was born illegitimately to Edward Grey 1st Viscount Fallodon (age 39). There is some uncertainty about the paternity.

On 21 Apr 1906 Stephen Tennant was born to Edward Tennant 1st Baron Glenconner (age 46) and Pamela Wyndham Viscountess Grey (age 35).

On 21 Apr 1918 Edward John Stanley 18th Earl of Derby was born to Edward Montagu Cavendish Stanley (age 23) and Sibyl Louise Beatrix Cadogan (age 25).

On 21 Apr 1922 Lieutenant David Hugh Joicey was born to Hugh Edward Joicey 3rd Baron (age 41) and Joan Katherine Lambton Baroness Joicey (age 28) at Chelsea. He ws educated at Eton College [Map] and Christ Church College, Oxford University for one year.

On 21 Apr 1926 Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom was born to King George VI of the United Kingdom (age 30) and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon Queen Consort England (age 25).

On 21 Apr 1945 Philip Sidney 2nd Viscount de L'Isle was born to William Philip Sidney 1st Viscount de l'Isle (age 35) and Jacqueline Vereker Countess de l'Isle (age 30). He a great x 3 grandson of King William IV of the United Kingdom.

On 21 Apr 1948 John Wayndham 7th Baron Leconfield 2nd Baron Egremont was born to John Edward Reginald Wyndham 6th Baron Leconfield 1st Baron Egremont (age 27) and Pamela Wyndham-Quin Baroness Leconfield and Egremont (age 22).

On 21 Apr 1951 John Grimston 7th Earl of Verulam was born to John Grimston 6th Earl of Verulam (age 38).

Marriages on the 21st April

On 21 Apr 1541 Archibald Campbell 4th Earl Argyll (age 34) and Margaret Graham Countess Argyll were married. She by marriage Countess Argyll. She the daughter of William Graham 3rd Earl Menteith (age 41). He the son of Colin Campbell 3rd Earl Argyll and Jean or Janet Gordon Countess Argyll. He a great x 5 grandson of King Edward III of England.

On 21 Apr 1577 Henry Herbert 2nd Earl Pembroke (age 39) and Mary Sidney Countess Pembroke (age 15) were married. She by marriage Countess Pembroke. The difference in their ages was 23 years. He the son of William Herbert 1st Earl Pembroke and Anne Parr Countess Pembroke.

On 21 Apr 1590 Henry Hobart 1st Baronet (age 30) and Dorothy Bell Lady Hobart were married.

On 21 Apr 1629 John Tufton 2nd Earl of Thanet (age 20) and Margaret Sackville Countess Isle Thanet (age 14) were married. She the daughter of Richard Sackville 3rd Earl Dorset and Anne Clifford Countess Dorset and Pembroke (age 39). He the son of Nicholas Tufton 1st Earl of Thanet (age 51) and Frances Cecil Countess Isle Thanet (age 48).

Before 21 Apr 1665 George Neville 11th and 9th Baron Bergavenny (age 50) and Mary Gifford Baroness Bergavenny (age 35) were married. She by marriage Baroness Bergavenny.

Before 21 Apr 1707 Charles Gerard 6th Baron Gerard (age 48) and Mary Webb Baroness Gerard were married.

On 21 Apr 1741 Jacob Bouverie 1st Viscount Folkestone (age 46) and Elizabeth Marsham Viscountess Fokestone (age 29) were married at Swanscombe, Kent.

Before 21 Apr 1749 William ffolkes1700-1773 (age 48) and Mary Browne (age 31) were married.

On 21 Apr 1757 Reverend Newton Ogle (age 31) and Susanna Thomas (age 23) were married. She the daughter of Bishop John Thomas (age 60).

On 21 Apr 1778 Francis Dickins and Diana Manners Sutton were married.

On 21 Apr 1792 Kemeys Radcliffe (age 26) and Mary Magdalana Tealing of Putney were married at St Paul's Church, Covent Garden. His aunt Emilia Anne Pond was witness.

On 21 Apr 1794 Lawrence Dundas 1st Earl Zetland (age 28) and Harriet Hale Baroness Dundas (age 24) were married at Gainsborough [Map].

On 21 Apr 1829 Charles George Perceval (age 32) and Mary Knapp were married.

On 21 Apr 1840 Alfred Wodehouse (age 25) and Emma Hamilton Macdonald Macdonald were married.

Before 21 Apr 1853 Reverend Nunn Robert Pretyman Kemp of Erpingham in Norfolk (age 39) and Mary Harriet Hagar were married.

On 21 Apr 1857 Charles Goring 9th Baronet (age 28) and Eliza Molyneux Lady Goring (age 21) were married.

On 21 Apr 1858 Henry Thynne Lascelles 4th Earl Harewood (age 33) and Diana Smyth Countess Harewood (age 20) were married. She by marriage Countess Harewood in Yorkshire. He the son of Henry Lascelles 3rd Earl Harewood and Louisa Thynne Countess Harewood (age 57). She a great x 5 granddaughter of King James II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Apr 1885 Henry Meysey-Thompson 1st Baron Knaresborough (age 39) and Ethel Adeline Pottinger Baroness Knaresborough (age 21) were married.

On 21 Apr 1887 Henry George Grosvenor (age 25) and Dora Mina Erskine-Wemyss (age 31) were married. He the son of Hugh Lupus Grosvenor 1st Duke Westminster (age 61) and Constance Leveson-Gower Duchess Westminster. She a great granddaughter of King William IV of the United Kingdom.

On 21 Apr 1891 Edward Lewis Birkbeck (age 30) and Emily Augusta Seymour (age 24) were married. She a great x 5 granddaughter of King James II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Apr 1910 Brigadier-General George Francis Milner (age 47) and Phyllis Mary Lycett Green were married.

On 21 Apr 1920 Harold Macmillan 1st Earl Stockton (age 26) and Dorothy Evelyn Cavendish (age 19) were married. She the daughter of Victor Christian William Cavendish 9th Duke Devonshire (age 51) and Evelyn Emily Mary Petty-Fitzmaurice Duchess Devonshire (age 49).

On 21 Apr 1921 Walter Scott 8th Duke Buccleuch 10th Duke Queensberry (age 26) and Vreda Lascelles Duchess Buccleuch and Queensbury (age 20) were married. He the son of John Scott 7th Duke Buccleuch 9th Duke Queensberry (age 57) and Margaret Alice "Molly" Bridgeman Duchess Buccleuch Duchess Queensbury (age 49).

On 01 Apr 1928 or 21 Apr 1928 Evan Morgan 2nd Viscount Tredegar (age 34) and Lois Sturt (age 27) were married.

On 21 Apr 1956 Colin Tennant 3rd Baron Glenconner (age 29) and Anne Veronica Coke Baroness Glenconner (age 23) were married at St Withburga's Church, Holkham [Map]. Bishop Percy Herbert (age 70) presided. The guests included Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon Queen Consort England (age 55) and Princess Margaret (age 25). Princess Margaret's future husband Antony Armstrong-Jones 1st Earl of Snowdon (age 26) took the photographs. She the daughter of Major Thomas William Edward Coke 5th Earl of Leicester (age 47) and Elizabeth Mary Yorke Countess of Leicester (age 44).

Deaths on the 21st April

On 21 Apr 1073 Pope Alexander II (age 63) died.

On 21 Apr 1135 Maud Penthièvre (age 54) died.

On 21 Apr 1136 Stephen Penthièvre Count Tréguier (age 76) died.

On 21 Apr 1162 Hawyse aka Denise de Dunstanville (age 24) died.

On 21 Apr 1329 Frederick "Fighter" Metz IV Duke Lorraine (age 47) died. His son Rudolph "Valiant" Metz I Duke Lorraine (age 9) succeeded I Duke Lorraine.

On 21 Apr 1421 John Fitzalan 13th Earl of Arundel (age 35) died. His son John Fitzalan 14th Earl of Arundel (age 13) succeeded 14th Earl Arundel Sussex, 4th Baron Maltravers, 4th Baron Arundel. Constance Cornwall Countess of Arundel by marriage Countess Arundel Sussex.

On 21 Apr 1421 or 26 Apr 1421 John Stewart of Innermeath 3rd of Lorn (age 71) died at Lorn.

On 21 Apr 1463 Nicholas Arundell (age 63) died.

On 21 Apr 1472 Joan Stourton (age 54) died.

Before 21 Apr 1499 Peter Middleton of Stokeld (age 57) died.

On 21 Apr 1509 King Henry VII of England and Ireland (age 52) died of tuberculosis at Richmond Palace [Map]. His son Henry VIII (age 17) succeeded VIII King England. Duke York and Earl Chester merged with the Crown.

On 21 Apr 1526 Anne St Leger Baroness Ros of Helmsley (age 50) died. She was buried with her husband in the St Leger Chantry, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle [Map].

On 21 Apr 1539 Unamed Habsburg Spain died.

On 21 Apr 1540 Afonso Aviz (age 30) died.

On 21 Apr 1541 James Stewart died.

On 21 Apr 1548 Anne Dacre Baroness Conyers (age 47) died.

On 21 Apr 1556 John Throckmorton (age 27) was hanged at Tyburn [Map].

On 21 Apr 1560 Thomas Babington (age 45) died.

On 21 Apr 1566 Richard Sackville (age 59) died.

On 21 Apr 1574 Cosimo I de Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany (age 54) died. His son Francesco I de Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany (age 33) succeeded I Grand Duke Tuscany.

On 21 Apr 1582 Oliver St John 1st Baron St John (age 60) died. His son John St John 2nd Baron St John (age 47) succeeded 2nd Baron St John of Bletso. Katherine Dormer Baroness St John Bletso by marriage Baroness St John of Bletso.

On 03 Oct 1584 Gilbert Dethick (age 74) died. Robert Cooke (age 49) served as Acting Garter King of Arms until the appointment of Gilbert's son William Dethick (age 44) on 21 Apr 1586.

On 21 Apr 1590 Kenelm Digby (age 72) died.

On 21 Apr 1593 John Cotton (age 81) died.

On or before 21 Apr 1645 Jane Hilton died.

On 21 Apr 1658 Jane Goodwin Baroness Wharton (age 40) died.

Between 21 Apr 1690 and 31 May 1694 Captain Edward Dymoke died.

On 21 Apr 1691 George Howard 4th Earl Suffolk (age 65) died. His brother Henry Howard 5th Earl Suffolk (age 63) succeeded 5th Earl Suffolk. Mary Upton Countess Suffolk (age 41) by marriage Countess Suffolk.

On 21 Apr 1691 Catherine Ward (age 28) died.

On 21 Apr 1696 D'Aubigny Turbeville died. Memorial at Salisbury Cathedral [Map].

On 21 Apr 1696 Daubigny Turberville (age 84) died at Salisbury. He was buried at Salisbury Cathedral [Map].

On 21 Apr 1698 Dorothy North Baroness Dacre of Gilsland (age 93) died.

On 21 Apr 1707 Charles Gerard 6th Baron Gerard (age 48) died. His brother Philip Gerard 7th Baron Gerard (age 41) succeeded 7th Baron Gerard of Gerard's Bromley.

On 21 Apr 1715 Elizabeth Somner (age 46) died. She was buried at the Holy Cross Church, Seend.

On 21 Apr 1716 George Parker (age 66) died.

On 21 Apr 1719 Thomas Cave 3rd Baronet (age 38) died. His son Verney Cave 4th Baronet (age 14) succeeded 4th Baronet Cave of Stanford in Northamptonshire.

On 21 Apr 1720 Henry Oxenden 4th Baronet (age 29) died without issue. His brother George Oxenden 5th Baronet (age 25) succeeded 5th Baronet Oxenden of Dene in Kent. Elizabeth Dunch Lady Oxenden (age 9) by marriage Lady Oxenden of Dene in Kent.

On 21 Apr 1721 Dorothea Louise Oldenburg (age 57) died.

On 21 Apr 1730 James Stanhope (age 8) died.

On 21 Apr 1748 Anne Hamilton 2nd Countess Ruglen (age 52) died. Her son William Douglas 4th Duke Queensberry (age 23) succeeded 3rd Earl Ruglen.

On 21 Apr 1753 Dorothy Reade died.

On 21 Apr 1761 Godfrey Copley (age 54) died. He was buried at St Mary’s Church, Sprotbrough [Map].

Godfrey Copley: In 1707 he was born to Lionel Copley and Maria Wilson aka Burrill.

On 21 Apr 1762 Roger L'Estrange 7th Baronet (age 80) died. Baronet Strange of Hunstanton in Norfolk extinct.

On 08 Apr 1770 or 21 Apr 1770 Lister Holte 5th Baronet (age 49) died. His brother Charles Holte 6th Baronet (age 48) succeeded 6th Baronet Holte of Aston in Warwickshire and inherited Brereton Hall, Cheshire [Map].

On 21 Apr 1770 Samuel Sandys 1st Baron Sandys (age 74) died after having been injured when his post-chaise overturned on Highgate Hill Highgate. His son Edwin Sandys 2nd Baron Sandys (age 43) succeeded 2nd Baron Sandys of Ombersley in Worcestershire.

On 21 Apr 1771 Other Lewis Windsor 4th Earl Plymouth (age 39) died. His son Other Windsor 5th Earl Plymouth (age 19) succeeded 5th Earl Plymouth, 11th Baron Windsor of Stanwell in Buckinghamshire.

On 21 Apr 1781 Thomas Laurence Dundas 1st Baronet (age 71) died. His son Thomas Dundas 1st Baron Dundas (age 40) succeeded 2nd Baronet Dundas of Kerse also inheriting Aske Hall North Yorkshire. Charlotte Fitzwilliam Baroness Dundas (age 34) by marriage Lady Dundas of Kerse.

On 21 Apr 1781 Henry Roper 10th Baron Teynham (age 73) died. His son Henry Roper 11th Baron Teynham (age 47) succeeded 11th Baron Teynham of Teynham in Kent.

On 21 Apr 1782 John Smith Burgh 11th Earl Clanricarde (age 61) died. His son Henry Burgh 1st Marquess Clarincade (age 40) succeeded 12th Earl Clanricarde.

On 21 Apr 1784 Charlotte Herbert (age 10) died.

On 17 Apr 1787 Nigel Gresley 6th Baronet (age 60) died. He was buried on 21 Apr 1787 in Bath Abbey [Map]. His son Nigel Bowyer Gresley 7th Baronet (age 34) succeeded 7th Baronet Gresley of Drakelow in Derbyshire.

On 21 Apr 1793 John Mitchell (age 68) died.

On 21 Apr 1799 Robert Sherard 4th Earl Harborough (age 86) died. His son Philip Sherard 5th Earl Harborough (age 32) succeeded 5th Earl Harborough, 5th Viscount Sherard, 7th Baron Sherard of Leitrim, 5th Baron Sherard of Harborough.

On 21 Apr 1806 William Tatton Egerton (age 56) died.

On 21 Apr 1823 Mary Scott (age 53) died.

On 21 Apr 1828 Archbishop Charles Manners-Sutton (age 73) died at Lambeth Palace [Map].

On 21 Apr 1829 Alice Hamilton-Gordon (age 19) died.

On 21 Apr 1829 Brook William Bridges 4th Baronet (age 61) died. His son Brook William Bridges 1st Baron FitzWalter (age 27) succeeded 5th Baronet Bridges of Goodneston in Kent.

On 21 Apr 1832 James Henry Blake 3rd Baronet (age 62) died. His son Henry Charles Blake 4th Baronet (age 37) succeeded 4th Baronet Blake of Langham in Suffolk.

On 21 Apr 1834 Frances Evelyn died.

On 21 Apr 1843 Prince Augustus Frederick Hanover 1st Duke Sussex (age 70) died at Kensington Palace. He was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery. Duke Sussex extinct.

On 21 Apr 1846 William Boothby 8th Baronet (age 64) died at Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire [Map]. His son Reverend Brooke William Boothby 9th Baronet (age 37) succeeded 9th Baronet Boothby of Broadlow Ash in Derbyshire.

On 21 Apr 1847 Bishop Walter Augustus Shirley (age 49) died at Bishop's Court Isle of Man.

On 21 Apr 1863 Robert Bateson 1st Baronet (age 81) died. His son Thomas Bateson 1st Baron Deramore (age 43) succeeded 2nd Baronet Bateson of Belvoir Park in County Down.

On 21 Apr 1868 Francis Wood 3rd Baronet (age 34) died. His son Matthew Wood 4th Baronet (age 10) succeeded 4th Baronet Wood of Hatherley House in Gloucestershire.

On 21 Apr 1870 Juliana Whitbread Countess Leicester (age 44) died. Memorial at St Withburga's Church, Holkham [Map] sculpted by Joseph Edgar Boehm (age 35).

Juliana Whitbread Countess Leicester:

On 03 Jun 1825 she was born to Samuel Charles Whitbread and Julia Brand.

On 20 Apr 1843 Thomas Coke 2nd Earl of Leicester and she were married. She by marriage Countess of Leicester. He the son of Thomas Coke 1st Earl of Leicester and Anne Amelia Keppel Countess Leicester. He a great x 4 grandson of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland. She a great x 5 granddaughter of King Charles II of England Scotland and Ireland.

On 21 Apr 1875 Henry William Pickersgill (age 92) died.

On 21 Apr 1877 Alexander Bannerman 9th Baronet (age 54) died at Grosvenor Place, Belgravia. His second cousin George Bannerman 10th Baronet (age 49) succeeded 10th Baronet Bannerman of Elsick in Kincardineshire.

On 21 Apr 1881 Mary Brooke (age 71) died.

On 21 Apr 1881 Sarah Mary Compton Cavendish Countess Cawdor (age 67) died.

On 21 Apr 1883 Emily Pakenham died.

On 21 Apr 1892 Alexandrine Hohenzollern (age 89) died.

On 21 Apr 1892 Maria-Anne Wyndham (age 64) died.

On 21 Apr 1892 Jane Macan Countess of Antrim (age 67) died.

On 21 Apr 1893 Edward Henry Stanley 15th Earl of Derby (age 66) died at Knowsley, Lancashire. His brother Frederick Arthur Stanley 16th Earl of Derby (age 52) succeeded 16th Earl Derby, 10th Baronet Stanley of Bickerstaffe. Constance Villiers Countess Derby (age 53) by marriage Countess Derby.

On 21 Apr 1905 Francis Godolphin Pelham 5th Earl Chichester (age 60) died. His son Jocelyn Pelham 6th Earl Chichester (age 33) succeeded 6th Earl Chichester, 7th Baron Pelham of Stanmer in Sussex and 11th Baronet Pelham of Laughton. Ruth Buxton Countess Chichester by marriage Countess Chichester.

On 21 Apr 1907 Harriet Louisa Neville-Grenville died.

On 21 Apr 1909 Henry Holroyd 3rd Earl Sheffield (age 77) died unmarried. Earl Sheffield of Dunamore in Meath, Viscount Pevensey, Baron Sheffield of Dunamore in Meath and Baron Sheffield of Sheffield in Yorkshire extinct. His half first cousin once removed Edward Lyulph Stanley 4th Baron Stanley 3rd Baron Eddisbury (age 69) succeeded 4th Baron Sheffield of Roscommon in Roscommon.

On 21 Apr 1915 George Granville Campbell (age 64) died.

On 21 Apr 1916 Kenelm Edward Digby (age 79) died.

On 21 Apr 1917 Cecil James Parnell (age 18) died. He was buried at All Saints Church, Barnwell [Map]. TR1O/27027, 31st (Training Reserve) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). Died on service in United Kingdom.

Cecil James Parnell: Around 1899 he was born to Pharoah Parnell at Winwick, Huntingdonshire.

On 21 Apr 1917 Henry Molyneux Paget Howard 19th Earl Suffolk 12th Earl Berkshire (age 39) was killed in action when a piece of shrapnel entered his heart. His son Charles Howard 20th Earl of Suffolk, 13th Earl Berkshire (age 11) succeeded 20th Earl Suffolk, 13th Earl Berkshire.

On 21 Apr 1919 Archibald Ernest Orr-Ewing 3rd Baronet (age 66) died.

On 21 Apr 1926 Margaret Grace Pitt-Rivers (age 78) died.

On 21 Apr 1938 Mary Caroline Bertie Viscountess Fitzalan Derwent Derby (age 78) died.

On 21 Apr 1945 Clement Charles Cave-Browne-Cave 15th Baronet (age 48) died. His son Robert Cave-Browne-Cave 16th Baronet (age 15) succeeded 16th Baronet Cave of Stanford in Northamptonshire.

On 21 Apr 1955 Winifred Charlotte Jane Wellesley died.

On 21 Apr 1955 Adelaide Violet Cicely Monson died.

On 21 Apr 1957 Ronald Tracy McGarel-Hogg 4th Baron Magheramorne (age 92) died unmarried. Baron Magheramorne of Magheramorne in Antrim extinct. His first cousin once removed Kenneth Weir Hogg 6th Baronet (age 62) succeeded 6th Baronet Hogg of Upper Grosvenor Street in London.

On 21 Apr 1992 Vladimir Kirillovich Holstein Gottorp Romanov (age 74) died.

On 21 Apr 1994 John Fremantle 4th Baron Cottesloe (age 94) died. His son John Fremantle 5th Baron Cottesloe (age 67) succeeded 5th Baron Cottesloe of Swanbourne and Hardwick in Buckinghamshire, 5th Baronet Fremantle of Swanborne in Buckinghamshire.